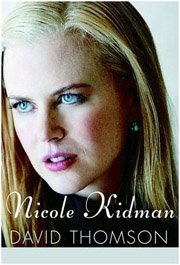

On Thursday, September 28, 2006, I made my way to Codys Bookstore in Berkeley to hear David Thomson speak on his latest book Nicole Kidman. Though attendance was slight, Thomson did not falter and offered a charming lecture, which I offer for your perusal.

* * *

People asked me while I was doing this book why I was doing it and they sort of looked at me as if I was dealing with something sleazy or something not quite wholesome. I could never understand what they thought they felt. I would answer with what I'm going to say to you: all my life I have gone to the movies and from the sort of first couple of times I went, I went back and kept going to see the people in movies. I certainly—when I was a kid—did not know the names of film directors. I did not know what directors did. To the degree that I began to read film posters as I could read, all the film posters really told me was that the film was sensational, extraordinary and wonderful—I thought they meant it honestly for a long time—and that so-and-so was in it and so-and-so was in it.

As I saw more films, I noticed something odd and, I thought, very interesting, which was that the man in this week's western—Winchester 73, let's say—was James Stewart and I had seen James Stewart only a few weeks—or a few months, perhaps—earlier, in a film I adored where he talked to a rabbit you couldn't see; a film called Harvey. It was a troubling thing to see that it was James Stewart again. I could recognize that it was James Stewart, but, still, I had the feeling when I started seeing movies that the absolute blinding wonderful uniqueness of the people up there on the screen was something that could not be repeated. In other words, it was a story about these people. The cameras had been lucky enough to observe and it had been brought to the screen. I didn't understand what actors were. If you think back to your childhood, it's much easier to believe—at least I found it much easier to believe—that people had these adventures and the adventures were somehow filmed. I didn't understand the film process—but that it worked like that and this was their film—than that there were actors who changed two or three times a year perhaps, did two or three different stories a year, and I remember thinking in a childlike way does the man in Winchester 73 remember or know that there's a rabbit in his life?

You've all been through this, I think, because when you're a child the movies are so miraculous that you hardly know where to begin asking questions about them. I could not comprehend for years how the image got on the screen. Whenever my parents tried to explain it to me, I gave up trying to understand it. It was much easier, in other words, to believe somehow that there was a magical window that opened onto some part of New York, or some part of the West in the 19th century, and that you were actually looking back through time and space at these stories, which had been beautifully organized for you so that all the dull stuff had been cut out.

As you grow older, you come to realize that really just the same relatively small bunch of people make the movies, make all of them, and that actors like John Wayne, Cary Grant, may have made 150 films in their time. You will talk with your school friends and you'll say, "Shall we go to see the western that's playing at our local theater this week?" Where I lived in London in those days the films changed once a week. They had a regular supply. But if you were very sophisticated, you said, "Well, is it a James Stewart western or a John Wayne western?" Because you were beginning to know that there were certain differences. Now, at that age, it would have been very hard to explain the differences. But Wayne was sterner—not necessarily braver—but more impervious to fear and danger and troubles. Stewart was gentler, more vulnerable. It was as if something of those real people was creeping into their performances.

As time passed still further and as television entered one's life, even in England occasionally there would be a talk show and on would come Jimmy Stewart, looking exactly like the man you knew from the westerns, talking not quite in the same way, but prepared—if asked by the interviewer—to fall into that very yawning, hesitating, slightly western way of talking, which was not James Stewart's real way of talking, but it was the way he talked when he made westerns. It was the way he talked, indeed, when he talked to Harvey the rabbit. A great mystery began to open up—which only made the movies more appealing and more compelling to me—which was that the characters I was seeing partook in some way of the real identity and nature of these actors. You couldn't confuse the actors of being the real people. They weren't. They had not actually shot someone down on Main Street at high noon. They hadn't done these things and yet they had done them with a force and a beauty and a power that lingered in your dreams and your daydreams. I guess really what I'm saying is that I'm a child of the movie generation and—as I look at your ages—some of the rest of you are too. You had this experience of growing up with people you liked.

Now there's a white-haired lady back there. I don't mean to pick on you but you're probably my age? [Older, she responds, much older. Thomson chuckles.] If you say much older, I dare say you have strong opinions as to whether you prefer Joan Crawford or Bette Davis? I won't ask you the opinion. I doubt you have met either of them. You probably know what you know about their real lives through the sketchiest and most unreliable of forms, but there was something maybe about Bette Davis that impressed you more than Joan Crawford. There I'm taking a gamble. Am I right? [She concurs.] You see? You can tell sometimes. You really can tell. Which is not to say anything against Joan Crawford. But the industrialists who made movies and who really knew that they were marketing personalities, they knew these things.

They didn't know at the very beginning of the film industry. When they first made films, they didn't put the names of actors on the films. The managers of theaters would telephone the people who would distribute the films to them and they'd say, "We're getting an awful lot of inquiries"; an awful lot of people who saw Flora Dora at the Beach or whatever [would] say, "Who was that girl?" They'd want to know who that girl was and they'd want her back next week.

All of a sudden stardom was born because you had to give these people names. Sometimes it turned out that the actress playing Flora Dora's name was Irena Krujinsky, which at those days was not going to work, on the posters, on the ads, no one was going to get the name right so she became—I don't know—Irene Dunn. Not Irene Dunn, that's another real actress, but something you could remember and you could latch onto. Magazines started and there were stories about these people. These magazines are preserved and they make wonderful reading because they were almost entirely made up, they were stories just like the stories you saw on the screen, but they tried to tell you that Irena Krujinsky was a lovely, sweet girl who knitted at home and wrote to her mother once a week and she had a couple of puppies. Absolutely made up. But it was done to make you like them more.

Or, it might be someone else, not quite such a good girl, didn't have puppies, didn't keep in touch with mother, was seen out at a couple of nightclubs a week and was leading a little bit of what might be called a "fast" life. It could have, again, [been] absolutely made up but it appealed to a different kind of interpretation. From about 1910 onwards—and it goes on to this day—these personalities are marketed. The marketing could make a fortune for them, for people who control them, for people who guide them, for people who advise them and have an interest in them. It sometimes gets to the point where these people lose touch with who they are.

Now we enter what I think is truly fascinating territory. Why do people act? Why do some people act? Why are some people good at acting whereas other people would be terrified to walk up on a stage? It doesn't mean that people who are good at acting aren't terrified every day going before the camera or going up on stage; they usually are. Laurence Olivier—when he was about 60—had crippling stage fright. The most accomplished actor in the world, if you like, could hardly force himself to go on. He believed he was going to forget every line he had to say. Laurence Olivier by that stage could have made the whole play up and the audience would have sat there enraptured because he had such reputation and such esteem. He knew he was in the service of the play and he was terrified that he was going to let it down. The neurosis in acting is enormous.

I've been fascinated by it all my life and—in time of course—I've actually worked with actors. I've met a lot of them and I've come to write a book about one of them. The first, principal reason why I wrote a book about Nicole Kidman is because I am fascinated by acting and the relationship between being a person and being an actor. Because—and I talk about this at great length in the book—it's my experience and I've met a lot of actors, I don't offer this as an absolute generalization but I think it's true more often than not—great actors are very uneasy with themselves. They do not quite know who they are. They need to pretend to be other people. It's a very frightening thing. And the job of acting is not nearly as pleasant as Entertainment Tonight, etc. makes it out to be. It's a very hard life, you all know. Any fan of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford know they both ended up pretty wretched, and they were both turned upon by children or adopted children who said—when their mothers were gone or even before their mothers were gone—let me tell you what it was like being her daughter and having to smile for the cameras when they came around from Photoplay and the magazines because, oh, we've got to do a piece on mommy and her children.

There's a book called Mommie, Dearest written by Joan Crawford's adopted daughter Christina that came out in the late '70s; a milestone in this kind of muckraking. But, clearly, a cry from the heart from that child who had had the most miserable life as she said because she was a bit part player in Joan Crawford's life. Now, some people say she had been very hard on her mother and very cruel; but, an awful lot of the children of actors say the same kind of thing. They say, "I've seen my mother on screen with children I've never met and she's been mothering them and she's so good at mothering them on screen I sometimes wish she was like that with me." Tough predicaments and endlessly insoluble, you can't come up with an answer. Different people, of course, handle it in different ways.

But I wanted to get into that kind of life and situation. I wanted to write about somebody who I think is really a star. Now, once upon a time we had movie stars and everyone knew who they were and nowadays we have a few stars, real stars, and a lot of people who are actors in films for a few years and then fade away. Nicole Kidman has been a star for about half her life. She's powerful. What do I mean by that? Well, in November a film is going to open called Fur, which is a story about the great American photographer Diane Arbus. That's a film that was trying to be made. In other words, people were trying to make it for about 10 years. It had so unusual an approach to its subject that they could not get it funded until Nicole Kidman came along and read the script and said, "I'll do it. I'll do it for much less than I'm usually paid." She is paid at the moment—or can be paid as much as any actress is paid at the moment—in the region of $15-$20,000,000 for a picture. She said, "I'll do it for much less. I'll take a percentage of the gross but I'll gamble that it's going to work if that will let you get it made." They got the film made and—when the film comes along in November—I hope you'll go see it because it's exactly typical of her daring, her willingness to do things that a lot of actresses would not do, and to get into a material and a subject matter that is disconcerting sometimes, alarming, novel, dangerous. She's a risk taking actress and she's still got the charisma of a star, partly for physical reasons. She's very tall. She has this amazing china quality skin and she's got the look that will photograph.

Another little thing about acting, let me just at random ask this group here: in our lives we are quite often these days photographed by relatives, by friends, by people who need our image for identification purposes. How many people here enjoy being photographed? [I was one of two to raise my hand.] I think most people—backed by this quick survey—are edgy, nervous, insecure about being photographed. Actors in film love to be photographed. They believe they were born to be photographed. They know—they do not think—they know they have a relationship with the camera. It's not enough to say they're vain because it's not a matter of vanity. It's not enough to say they're beautiful, or goodlooking, or exceptional looking, although they probably are. They have a relationship to the camera. The camera is their white rabbit, their intimate, their confidante. They know the camera understands them and they trust the camera in a way many of us don't. They like to be photographed and they like to go to work. They like to pretend they are other people. Which is not the easiest thing if they're trying to live with other people. I mean, if you go home tonight after this event and you've got—I don't know—companions at home, spouses, siblings, children, parents, and you come in the door and they say, "Oh, I have something I need you for." It's not terribly good for the relationship if you say, "Hush darling, I'm still being Virginia Woolf. Or I'm still being Diane Arbus." Because your kids or your parents will get sick of it pretty quickly. It will damage, it will endanger, your life.

But if you have all day been filming a scene where you're Virginia Woolf, and it's a scene, let's say, where Virginia Woolf is either wondering what the first sentence of Mrs. Dalloway will be, or she's wondering whether she can pluck up the courage to tell the servants what to cook for dinner, or whether she will go commit suicide this afternoon, and if the director keeps saying, "Nicole, you're not quite there" and you've got to get into it just that little bit more, just that little bit more where it begins to become dangerous. Well, you'd probably need to be driven home because you may not be in the best state for driving and, when you get home, exhausted, because—whatever else, filmmaking is physically exhausting, you may have had to do that scene 25 times—if your child says, "Mommy, can you help me with my homework?" You might easily say, "Not tonight." Which is a pity, for the homework, and for the child, and for the actresses's hopes at sustaining a natural life. If only for this reason that if you are an actress, and if you're doing good work, you know that part of it is pretending—and pretending is kind of a pure game—but part of it is knowing enough about life to know what everyone else fears. So it's looking at your child's face when you say, "I'm too tired tonight" and seeing the disappointment, and looking at that look of disappointment, and saying, "I've got to remember that look because a film may come along in a couple of years where I need exactly that look of disappointment." It's cannibalism in a strange sort of way.

I'm making it a very extreme collision course, but, it has a lot to do with why a lot of actors and actresses end up quite unhappy people, no matter that they may have brought immense happiness to millions. It's a very strange trade to be loved by strangers. All of those things drew me to the fact, plus—and I couldn't have done this book if this was not true—if I had been 5 or 65, I like Nicole Kidman in the way that Sandra Bullock, for me, okay, I understand people are crazy about Sandra Bullock but I think she's sort of ordinary. Nicole Kidman turns me on. I do not mean that in a sort of direct sexually desiring way, but in a fantasy way, and we all fantasize all the time when we go to the movies.

So that's really what's behind this book. I'm stepping into a genre—the star biography—that's a pretty trashy form. A lot of these books are ghostwritten by hack journalists who interview the star for two days and they turn it into something. I had finished this book before Nicole Kidman agreed to talk to me. I had approached her through her people very early on and the answer came back that she was interested but she was too busy. Understandable. She works very hard. Only very near the end, when I actually had a first draft, did her people call me and say, "Are you still interested in talking to her? Because she's got a window of opportunity coming up. And if it coincides with your window of opportunity"—my windows are so much more flexible—"maybe we can do something." She talked to me for an hour on the phone and she was decent, funny, and human, and natural, just like a real person. She didn't really say anything revealing because I think she'd made up her mind that she would not, but that she would collaborate with the book. She said, "Of course, one day"—and I've never met an actor or actress of whom this isn't true—"one day I'll do my own book." Occasionally they do. Bette Davis wrote a very good book called My Lonely Life. Not too many actors and actresses have it in them to write a book or even to dictate it and by the end—when they might think of doing that—they're cracking up in a lot of ways and so they don't actually get around to it.

I know a good deal about film. I know a good deal about acting. I was able to get to a lot of people she's worked with who talked to me candidly about what it was like. They were nearly all of them intensely admiring of her and that's the fruit that's in this book. It's a book about someone who will be 40 next year so it's certainly not a book that makes up its mind about anything important. Except to say that to be 40 for an actress is a very very frightening moment. You don't see too many women over 40 playing lead roles in American movies. Indeed, if you look at American movies these days, you could believe that something quite mysterious happens in this country where beyond about 45 people are locked away in closets; beyond 60, well, they just don't exist. We don't have people over 60 in this country. It's not even anything decent or nice that you want to talk about. So we don't make films about people when they have actually reached the stage of life when, I think, they're most interesting. Because they've learned the most. Because they've got the most to pass on to you. Their hopes have become more realistic and when their ability to convey what they think has improved a good deal. A tragedy. A terrible cultural failing in our cinema. This awful, awful stress upon youth and—beautiful as she is—I think Nicole Kidman knows how to look in the mirror and see warning signs. I think she's been seeing them for a few years and I actually think she's been doing a few things about them, which—generally speaking—is not a good move these days. Because the things you do about them tend to draw attention to the problem. As we all know, as we grow older, people who are 40, and 60, and 80 look terrific. They look like human beings. What more can you ask?

So it's a frightening time for her. It's a frightening time too because she's gotten used in some ways to earning $15-$20,000,000 a time. Habits form quite easily around things like that. She has a lot of people to support. People to look after her: agents, lawyers, managers, pr people, people to look after her children when she's not there—which is quite a lot of the time—people to drive her, people to keep the fans back, people who will sit in a restaurant and make sure no one makes an attack upon her, when she goes out she goes out with people like that. They have to be paid for. She could choose to say, "I won't take $15,000,000 for this film; I'll just take $1,500,000." Just $1,500,000 for 10 weeks work. It's a very big concession on her part. But every time she does it, she gambles that someone's going to come along and say, "Will you make Bewitched?"—even though Bewitched was a silly waste of time—"and we'll give you $20,000,000." If her looks begin to go enough, they won't do that, and she will have to adjust her whole standard of living and her whole career and that's frightening. Those are the kind of things I talk about in this book.

I just wanted to sort of let you realize that a serious person—such as myself—can take an actress very seriously. There have been a few reviews of this book that have said, "Well, it's really unworthy of a film professor, a historian like David Thomson, to just write about an actress." I beg to differ. I don't think there's anything closer to the heart with movies than acting. I still go to see people in movies. I would still go to see any film she makes. I would still go to see any film Johnny Depp makes because they both have—call it a charm—something that the camera seems to like. Denzel Washington. There are maybe 10 people today who really have it. In 1930, 1940, there were a lot more who had it because stardom was just—well, there were more stars around.

I hope we're not going to lose stars. I hope we're not going to let stardom be eclipsed by this dreadful sort of mock version of it called celebrity, where everyone knows they're a celebrity for a very short time and it's gone. That's really what this book is about. It's a very serious book about a wonderful, universal subject and, I think, a very brave, independent, risk taking young woman. Somebody James Stewart would have liked.

Cross-posted at Twitch.

11/09/06 UPDATE: Steve Jenkins wryly reviews David Thomson's latest at The Greencine Daily. "Many readers," Steve writes, "have been put off by the naked yearning with which Thompson expresses his devotion throughout the book, but I don't find his approach inherently troubling. Desire is indeed a crucial component of our best and worst moviegoing experiences and their lifelong aftereffects, and delving into this sticky territory of unhealthy adoration seems bravely foolish, and certainly more welcome than yet another rote star bio that gingerly skirts messy obsession."