With this entry, I wrap up my coverage of the first-ever TCM Classic Film Festival with many thanks to TCM's publicist Sarah Schmitz and Caitlin McGee at L.A.'s mPRm Public Relations. I've already written some on TCM's Road to Hollywood tour, which built up to the TCM Classic Film Festival with a set of five local events. Attended by enthusiastic fans, the pre-festival Road to Hollywood celebrations featured free screenings in New York, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., with appearances by TCM host Robert Osborne, weekend daytime host Ben Mankiewicz, Oscar®-winning actress Eva Marie Saint, filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich, Broadway legend Elaine Stritch and others. Not only was this a conciliatory gesture to offset the hefty price tag for passes at the festival proper (the Road to Hollywood screenings were free to the public); but, each film was chosen as reflective of the city wherein it was screened. What better choice could there be for San Francisco than Orson Welles' 1948 film noir The Lady From Shanghai? And who better to introduce this memorable thriller than filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show), an expert on the films of Orson Welles and a close friend of the director, joined by San Francisco's KRON reporter Jan Wahl?

With this entry, I wrap up my coverage of the first-ever TCM Classic Film Festival with many thanks to TCM's publicist Sarah Schmitz and Caitlin McGee at L.A.'s mPRm Public Relations. I've already written some on TCM's Road to Hollywood tour, which built up to the TCM Classic Film Festival with a set of five local events. Attended by enthusiastic fans, the pre-festival Road to Hollywood celebrations featured free screenings in New York, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., with appearances by TCM host Robert Osborne, weekend daytime host Ben Mankiewicz, Oscar®-winning actress Eva Marie Saint, filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich, Broadway legend Elaine Stritch and others. Not only was this a conciliatory gesture to offset the hefty price tag for passes at the festival proper (the Road to Hollywood screenings were free to the public); but, each film was chosen as reflective of the city wherein it was screened. What better choice could there be for San Francisco than Orson Welles' 1948 film noir The Lady From Shanghai? And who better to introduce this memorable thriller than filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show), an expert on the films of Orson Welles and a close friend of the director, joined by San Francisco's KRON reporter Jan Wahl? Asked how Orson Welles might react if he knew that The Lady From Shanghai was being screened at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, Bogdanovich asserted Welles would have been thrilled. When Bogdanovich asked Orson Welles how people reacted when The Lady From Shanghai first opened, Welles told him people avoided the subject. If the film was mentioned, people would quickly change the subject. The first American who said anything nice about the film was Truman Capote when Welles met him in Sicily two years after The Lady From Shanghai came out. Capote even quoted lines from the movie. But other than for that, the film was not terribly well received.

Asked how Orson Welles might react if he knew that The Lady From Shanghai was being screened at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, Bogdanovich asserted Welles would have been thrilled. When Bogdanovich asked Orson Welles how people reacted when The Lady From Shanghai first opened, Welles told him people avoided the subject. If the film was mentioned, people would quickly change the subject. The first American who said anything nice about the film was Truman Capote when Welles met him in Sicily two years after The Lady From Shanghai came out. Capote even quoted lines from the movie. But other than for that, the film was not terribly well received.Bogdanovich met Welles in 1961 when he was asked to curate the first U.S. Orson Welles retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art. He'd been invited to curate the retrospective because he had written a nice program note about Othello (1952), which Bogdanovich hailed as "the best Shakespeare film ever made." Once he agreed to curate the show, Bogdanovich wrote a monograph, which was sent off to Welles in Europe where he was making The Trial (1962). Bogdanovich didn't hear anything at all from Welles for seven years.

He finally received a phone call where Welles announced himself and said, "I can't tell you how long I've been wanting to meet you. I'm staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel. What are you doing at 3:00 tomorrow?" Bogdanovich said, "Nothing. I'll meet you there." Though he was nervous as hell, Bogdanovich met Welles the following day. Welles was dressed in a loose caftan. They spent three hours talking and by the end of that conversation Bogdanovich felt like he'd known Orson Welles all his life. Bogdanovich had brought Welles a copy of the book he had written on John Ford, who he was aware was Orson Welles' favorite director. Leafing through the book Welles insinuated that it was too bad Bogdanovich hadn't written a book on him. Bogdanovich said he would welcome the opportunity to write a book of interviews with him and so their first interview was held on the set of Catch-22 (1970), which urban legend says is where Bogdanovich first met Welles, though that's not entirely accurate; they had met before.

He finally received a phone call where Welles announced himself and said, "I can't tell you how long I've been wanting to meet you. I'm staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel. What are you doing at 3:00 tomorrow?" Bogdanovich said, "Nothing. I'll meet you there." Though he was nervous as hell, Bogdanovich met Welles the following day. Welles was dressed in a loose caftan. They spent three hours talking and by the end of that conversation Bogdanovich felt like he'd known Orson Welles all his life. Bogdanovich had brought Welles a copy of the book he had written on John Ford, who he was aware was Orson Welles' favorite director. Leafing through the book Welles insinuated that it was too bad Bogdanovich hadn't written a book on him. Bogdanovich said he would welcome the opportunity to write a book of interviews with him and so their first interview was held on the set of Catch-22 (1970), which urban legend says is where Bogdanovich first met Welles, though that's not entirely accurate; they had met before. With regard to The Lady From Shanghai, apparently Harry Cohn—who was running Columbia Pictures—was angry at Welles because of his influence on Rita Hayworth, even though their marriage was faltering and they were estranged during the filming of The Lady From Shanghai. Cohn was upset that Welles convinced Hayworth to give up her red tresses, and dye her hair blonde and cut it short. After the shoot was over, Cohn swore he would never make another picture where the director and producer was also the star. "I had nobody to fire," he complained, "I might as well be the janitor."

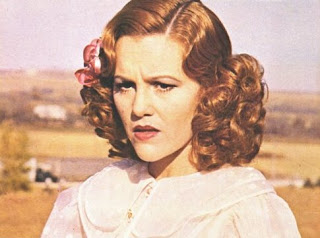

With regard to The Lady From Shanghai, apparently Harry Cohn—who was running Columbia Pictures—was angry at Welles because of his influence on Rita Hayworth, even though their marriage was faltering and they were estranged during the filming of The Lady From Shanghai. Cohn was upset that Welles convinced Hayworth to give up her red tresses, and dye her hair blonde and cut it short. After the shoot was over, Cohn swore he would never make another picture where the director and producer was also the star. "I had nobody to fire," he complained, "I might as well be the janitor."Though some shooting took place at locations in San Francisco—such as Portsmouth Plaza, the Steinhart Aquarium in Golden Gate Park, and Whitney's Playland Amusement Park on the beach—other scenes were shot on sound stages, in Mexico and on Errol Flynn's yacht Zaca. Evidently, Flynn is even in a couple of scenes, though not so he can be recognized. Under contract to Warners, he wasn't about to give Cohn that pleasure.

The Lady From Shanghai was not fully the picture that Orson Welles wanted; but, then again, he rarely achieved the pictures he envisioned. One major dissatisfaction for him was Heinz Roemheld's score, which he hated and had nothing to do with. For example, the mirror sequence at the end was not supposed to have any score at all and Bogdanovich imagined Welles gnashing his teeth every time he heard it.

The Lady From Shanghai was not fully the picture that Orson Welles wanted; but, then again, he rarely achieved the pictures he envisioned. One major dissatisfaction for him was Heinz Roemheld's score, which he hated and had nothing to do with. For example, the mirror sequence at the end was not supposed to have any score at all and Bogdanovich imagined Welles gnashing his teeth every time he heard it.At one point, Orson Welles moved in with Bogdanovich and—though he was fun to live with—he moreorless took over his house. "It was a big house too!" Bogdanovich emphasized. Welles had a room, and an anteroom and a bathroom, but pretty soon he was using the dining room table as his writing desk. One of Bogdanovich's happiest memories of that stay was when Orson Welles moved briskly through his office, saying, "Dick Van Dyke is on!" Welles loved watching reruns of The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Another time, Cybill Shepherd—who was also living with Bogdanovich—walked by the part of the house where Orson Welles was staying and she smelled something burning. She knocked on the door and said, "Orson, I smell something burning." He shouted back, "Yes, well I'd like a little privacy, please, that's all. Everything's fine." "But I smell something burning," she insisted. "Privacy is what's requested," he repeated. She didn't mention anything to Bogdanovich and later when both she and Orson were out of the house, Bogdanovich's housekeeper called out to him and said, "Mr. B., I think Mr. Welles had an accident." She had found his white terrycloth robe with a big burn mark in it. It turned out that he had put his lit cigar in the pocket of the robe and it had caught fire. So he had taken it off and thrown it into the bathtub but a part of it had fallen over the edge of the tub and had ignited the carpet. Welles said he would take care of it but he never did. A couple of days later a beautifully-wrapped book arrived for Cybill and when she opened it she found a beautifully-illustrated book about opera—she loved opera—and inside Orson had drawn a picture of a burning house with a ladybug in the foreground looking terrified. Underneath the drawing, Welles had written: "Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home. Your house is on fire and so is your houseguest. Love, Orson."

Another time, Cybill Shepherd—who was also living with Bogdanovich—walked by the part of the house where Orson Welles was staying and she smelled something burning. She knocked on the door and said, "Orson, I smell something burning." He shouted back, "Yes, well I'd like a little privacy, please, that's all. Everything's fine." "But I smell something burning," she insisted. "Privacy is what's requested," he repeated. She didn't mention anything to Bogdanovich and later when both she and Orson were out of the house, Bogdanovich's housekeeper called out to him and said, "Mr. B., I think Mr. Welles had an accident." She had found his white terrycloth robe with a big burn mark in it. It turned out that he had put his lit cigar in the pocket of the robe and it had caught fire. So he had taken it off and thrown it into the bathtub but a part of it had fallen over the edge of the tub and had ignited the carpet. Welles said he would take care of it but he never did. A couple of days later a beautifully-wrapped book arrived for Cybill and when she opened it she found a beautifully-illustrated book about opera—she loved opera—and inside Orson had drawn a picture of a burning house with a ladybug in the foreground looking terrified. Underneath the drawing, Welles had written: "Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home. Your house is on fire and so is your houseguest. Love, Orson." Orson Welles was also the individual responsible for the rule that there should never be "dead air" on the radio or television because of the way he scared half the country with his Halloween 1938 radio adaptation of War of the Worlds. Staged as a series of simulated news broadcasts—now unlawful— interrupting the normal musical programming, Welles had an eyewitness newscaster describing the alien craft that had allegedly landed in Princeton. The moment that specifically terrified America was when the announcer—who had gone to Princeton—was describing the green monster emerging from the space craft and suddenly let out a scream followed by silence, dead air. People who were in the studio where Welles was directing recount that he wouldn't let them break the silence. He kept gesturing to them to keep the pause going for a long time. The silence is what scared the shit out of everybody.

Orson Welles was also the individual responsible for the rule that there should never be "dead air" on the radio or television because of the way he scared half the country with his Halloween 1938 radio adaptation of War of the Worlds. Staged as a series of simulated news broadcasts—now unlawful— interrupting the normal musical programming, Welles had an eyewitness newscaster describing the alien craft that had allegedly landed in Princeton. The moment that specifically terrified America was when the announcer—who had gone to Princeton—was describing the green monster emerging from the space craft and suddenly let out a scream followed by silence, dead air. People who were in the studio where Welles was directing recount that he wouldn't let them break the silence. He kept gesturing to them to keep the pause going for a long time. The silence is what scared the shit out of everybody.Welles was also the one who advised Bogdanovich to film The Last Picture Show in black and white. When Bogdanovich asked him why, Welles explained, "Because your script is an actors story. Its an actors picture. And you know what I say about black and white?" "What, Orson?" "It's the actor's friend." "Why do you say that?" "Because every performance is better in black and white."

Along with recognizing Orson Welles' brilliance, Bogdanovich described him as being very funny. Bogdanovich had the honor of working with Welles on The Other Side of the Wind, an unfinished film directed by Welles starring Bogdanovich, John Huston, Dennis Hopper and Oja Kodar. Though Welles was kind to his actors, he could be a bit rough on his crew who were largely composed of volunteers or people who were not getting paid much. One day they had been there since 7:00 in the morning and it was already 3:00 in the afternoon and they hadn't broken for lunch. The assistant director nervously mentioned to Welles, "Uh Orson, the crew hasn't eaten. They've been here since 7:00 and it's already 3:00." "All right," Welles voiced irritably, "if they have to eat, let them go to lunch. I'm not hungry." Bogdanovich was sitting there and he said, "I'm not hungry either, Orson, I'll stay with you." "Fine!" Welles pronounced, "Peter and I will stay here while the crew goes to lunch." So the crew left for lunch and when Bogdanovich and Welles were finally alone, Welles turned and asked, "Are you hungry, Peter?" They went into the kitchen and on top of the refrigerator was an industrial-sized bag of Fritos. Welles picked it up, tore off the top, and poured the bag's contents onto the kitchen table. Welles sat down, took a big fist full of Fritos and shoved them in his mouth and—while crunching on them—said to Peter: "Y'know, you don't gain weight if nobody sees you eating."

Along with recognizing Orson Welles' brilliance, Bogdanovich described him as being very funny. Bogdanovich had the honor of working with Welles on The Other Side of the Wind, an unfinished film directed by Welles starring Bogdanovich, John Huston, Dennis Hopper and Oja Kodar. Though Welles was kind to his actors, he could be a bit rough on his crew who were largely composed of volunteers or people who were not getting paid much. One day they had been there since 7:00 in the morning and it was already 3:00 in the afternoon and they hadn't broken for lunch. The assistant director nervously mentioned to Welles, "Uh Orson, the crew hasn't eaten. They've been here since 7:00 and it's already 3:00." "All right," Welles voiced irritably, "if they have to eat, let them go to lunch. I'm not hungry." Bogdanovich was sitting there and he said, "I'm not hungry either, Orson, I'll stay with you." "Fine!" Welles pronounced, "Peter and I will stay here while the crew goes to lunch." So the crew left for lunch and when Bogdanovich and Welles were finally alone, Welles turned and asked, "Are you hungry, Peter?" They went into the kitchen and on top of the refrigerator was an industrial-sized bag of Fritos. Welles picked it up, tore off the top, and poured the bag's contents onto the kitchen table. Welles sat down, took a big fist full of Fritos and shoved them in his mouth and—while crunching on them—said to Peter: "Y'know, you don't gain weight if nobody sees you eating." Recalling that Bogdanovich had filmed What's Up, Doc? (1972) in San Francisco with Barbra Streisand, Wahl quipped that not too many people who have worked with Streisand have lived to talk about it and asked if Bogdanovich could share a bit of his experience working with her? "I loved working with her," Bogdanovich answered, "she was a lot of fun." She didn't like the script, though she had given up script approval; but, she did like Bogdanovich and he liked her. She would read the script and go, "You think this is funny? This is funny to you?" He would say, "I think it's really funny, Barbra." Then he'd suggest, "Why don't you read that line like this?" She would stop, stare at him, and say, "You're giving me a line reading?" He told her he was merely giving her an indication of how the line could be said. Her agent called him up and said, "You're giving Barbra Streisand line readings?!" Again, he explained he was just offering a suggestion on how the line could be read. Two weeks later she finally said, "Okay, how would you say it?" Then he would tell her and she would do it. Finally, when she was singing "As Time Goes By" for the film, Bogdanovich asked her, "You know that line where you say 'and on that you can rely'?" She said, "Yeah." He said, "Can you hit 'can'?" She retorted, "Now you're giving me line readings on the fucking song?!" But she did it.

Recalling that Bogdanovich had filmed What's Up, Doc? (1972) in San Francisco with Barbra Streisand, Wahl quipped that not too many people who have worked with Streisand have lived to talk about it and asked if Bogdanovich could share a bit of his experience working with her? "I loved working with her," Bogdanovich answered, "she was a lot of fun." She didn't like the script, though she had given up script approval; but, she did like Bogdanovich and he liked her. She would read the script and go, "You think this is funny? This is funny to you?" He would say, "I think it's really funny, Barbra." Then he'd suggest, "Why don't you read that line like this?" She would stop, stare at him, and say, "You're giving me a line reading?" He told her he was merely giving her an indication of how the line could be said. Her agent called him up and said, "You're giving Barbra Streisand line readings?!" Again, he explained he was just offering a suggestion on how the line could be read. Two weeks later she finally said, "Okay, how would you say it?" Then he would tell her and she would do it. Finally, when she was singing "As Time Goes By" for the film, Bogdanovich asked her, "You know that line where you say 'and on that you can rely'?" She said, "Yeah." He said, "Can you hit 'can'?" She retorted, "Now you're giving me line readings on the fucking song?!" But she did it.Bogdanovich mentioned that—if you listen to the DVD commentary for What's Up, Doc?—Streisand is very funny because she acts like she's never seen the movie. You hear her saying, "Oh, this is funny!" She said, "I don't know what to say about this, all I did was show up and did what he told me." Bogdanovich called her up and said, "I like what you said on the DVD." She said, "It's true, isn't it? I showed up and I did what you told me." But that wasn't exactly true because—when she first began working on the film with Bogdanovich—she told him flat out, "You know, I've never been directed." "Really?" he said, so while the picture was happening he would direct her along and she would protest, "What are you doing?" He said, "I'm directing." She said, "I'd like to take a moment here." He said, "No moment. There'll be no moments for the entire picture." She swore, "Jesus Christ!"

Towards the end of the film Streisand had a scene where she says the in-joke, "Love means never having to say you're sorry." When the time came to rehearse the scene, Bogdanovich told her to say "love means never having to say you're sorry" in one straight phrase and then blink her eyes. "Why?" she wanted to know. He explained he felt it took the heat off the line and made it funny. "Yeah?" she answered, "huh." So from then on in the two weeks left before they shot the scene she went to each and every person on the set and asked, "What's funnier? Love means never having to say you're sorry ... or ... love means never having to say you're sorry?" She went to her co-star Ryan O'Neal, "Ryan, which do you think is funnier?" Ryan said, "I don't know, Barbra. Peter's the director." Finally, the day they were supposed to shoot the scene, she said, "Okay, let's shoot it two ways." She wanted to shoot it with her saying the line the way she wanted to say it and then the way Bogdanovich wanted her to say it. Bogdanovich told her he wasn't going to do that; they were only going to shoot the scene once. "Why?" she wanted to know. "Because if we shoot it both ways," he told her, "from now until forever you'll be saying, 'Use this one. No use this one. No use this one.' " She retorted, "Jesus Christ!" Bogdanovich asserted, "This is called directing, Barbra." With total deadpan, Bogdanovich said, "I loved working with her."

Towards the end of the film Streisand had a scene where she says the in-joke, "Love means never having to say you're sorry." When the time came to rehearse the scene, Bogdanovich told her to say "love means never having to say you're sorry" in one straight phrase and then blink her eyes. "Why?" she wanted to know. He explained he felt it took the heat off the line and made it funny. "Yeah?" she answered, "huh." So from then on in the two weeks left before they shot the scene she went to each and every person on the set and asked, "What's funnier? Love means never having to say you're sorry ... or ... love means never having to say you're sorry?" She went to her co-star Ryan O'Neal, "Ryan, which do you think is funnier?" Ryan said, "I don't know, Barbra. Peter's the director." Finally, the day they were supposed to shoot the scene, she said, "Okay, let's shoot it two ways." She wanted to shoot it with her saying the line the way she wanted to say it and then the way Bogdanovich wanted her to say it. Bogdanovich told her he wasn't going to do that; they were only going to shoot the scene once. "Why?" she wanted to know. "Because if we shoot it both ways," he told her, "from now until forever you'll be saying, 'Use this one. No use this one. No use this one.' " She retorted, "Jesus Christ!" Bogdanovich asserted, "This is called directing, Barbra." With total deadpan, Bogdanovich said, "I loved working with her." As for working with Cher on Mask (1985), Bogdanovich was quick to opine that he did not love working with her. Directing Cher was like pulling teeth. He had to resort to a lot of close-ups because she couldn't sustain a scene for more than a few moments. She would start a scene one way and end up way over somewhere else and he would have to say, "Cher...." He admitted she was great in close-ups because she had all the suffering of the world in her eyes, "until you found out it was self-pity." The audience howled. He charged on, "The only good thing she had to say about Sonny was when he died. I love Cher."

As for working with Cher on Mask (1985), Bogdanovich was quick to opine that he did not love working with her. Directing Cher was like pulling teeth. He had to resort to a lot of close-ups because she couldn't sustain a scene for more than a few moments. She would start a scene one way and end up way over somewhere else and he would have to say, "Cher...." He admitted she was great in close-ups because she had all the suffering of the world in her eyes, "until you found out it was self-pity." The audience howled. He charged on, "The only good thing she had to say about Sonny was when he died. I love Cher." Wahl related that one of her favorite scenes in all of movies is in Paper Moon (1973) when Madeline Kahn is trying to convince Tatum O'Neal to come down off the hill. There's something so touching about that scene for her. Bogdanovich related that in that scene Kahn as Trixie Delight pleads with Tatum's character Addie to not screw things up for her with Moses Pray (Ryan O'Neal). She cajoles Addie into sitting in the back seat and letting Moses sit up front with her big tits. The first time they read the scene, Kahn said, "I'm not saying that." He said, "You're not going to say that?" "No," she answered. "Well, what do you want to say?" Bogdanovich asked. "Big breasts or big boobies or something," Kahn offered, "but I'm not going to say tits." "Okay," Bogdanovich said, letting it go. And, indeed, Kahn never said it until the day came to shoot the scene and just before they started rolling, he went up to her and whispered in her ear, "Say tits just once" and walked away, not sure if she would do it. She did it. When you see it in the picture, Bogdanovich pointed out, it was her one and only take and then afterwards there was this great moment because she had never said it and she had this kind of embarrassed smile, "which was heaven."

Wahl related that one of her favorite scenes in all of movies is in Paper Moon (1973) when Madeline Kahn is trying to convince Tatum O'Neal to come down off the hill. There's something so touching about that scene for her. Bogdanovich related that in that scene Kahn as Trixie Delight pleads with Tatum's character Addie to not screw things up for her with Moses Pray (Ryan O'Neal). She cajoles Addie into sitting in the back seat and letting Moses sit up front with her big tits. The first time they read the scene, Kahn said, "I'm not saying that." He said, "You're not going to say that?" "No," she answered. "Well, what do you want to say?" Bogdanovich asked. "Big breasts or big boobies or something," Kahn offered, "but I'm not going to say tits." "Okay," Bogdanovich said, letting it go. And, indeed, Kahn never said it until the day came to shoot the scene and just before they started rolling, he went up to her and whispered in her ear, "Say tits just once" and walked away, not sure if she would do it. She did it. When you see it in the picture, Bogdanovich pointed out, it was her one and only take and then afterwards there was this great moment because she had never said it and she had this kind of embarrassed smile, "which was heaven." Bogdanovich wrapped up by seizing the opportunity to tells stories that allowed him to do his infamous (and hilarious!) vocal impersonations of Cary Grant and James Stewart and then concluded with a complaint: "Nobody ever says, 'Have you seen that old play by Shakespeare?' Or, "Have you heard that old symphony by Mozart?' Or, 'Have you read that old novel by Hemingway?' No one ever says that. But they always say, 'Have you seen that old movie?' I don't like that because a movie—if you haven't seen it—it's not an old movie; it's a new movie."

Bogdanovich wrapped up by seizing the opportunity to tells stories that allowed him to do his infamous (and hilarious!) vocal impersonations of Cary Grant and James Stewart and then concluded with a complaint: "Nobody ever says, 'Have you seen that old play by Shakespeare?' Or, "Have you heard that old symphony by Mozart?' Or, 'Have you read that old novel by Hemingway?' No one ever says that. But they always say, 'Have you seen that old movie?' I don't like that because a movie—if you haven't seen it—it's not an old movie; it's a new movie."Cross-published on Twitch.