I've seen Ekachai Uekrongtham's Beautiful Boxer twice, first at the 47th San Francisco International Film Festival on April 18, 2004. At that time, I wrote:

I've seen Ekachai Uekrongtham's Beautiful Boxer twice, first at the 47th San Francisco International Film Festival on April 18, 2004. At that time, I wrote:Even Roger Garcia had trouble pronouncing Ekachai Uekrongtham's name when introducing him to his Castro Theater audience for last night's U.S. premiere screening of Beautiful Boxer. Uekrongtham admitted he had no idea when he made this film that it would travel as far as it has and originally worried that there would only be two people in his audience.

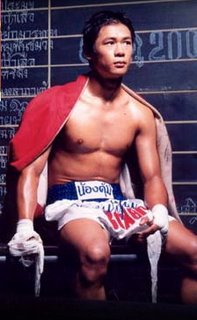

Uekrongtham's debut feature film is held aloft by the sincere, superb performance of Sanee Suwan in the role of Parinya Charoenphol (more generally known as Nong Toom). Suwan was named Best Boxer by the Association of Muay Thai (i.e., Thai kickboxing) for the northern region of Thailand in 2001 and this skill was beautifully evident in the film's boxing sequences, which really were quite exciting to watch.

The movie starts out with a kick. A journalist is trying to chase down Nong Toom to interview her, accidentally knocks over a woman whose hulky boyfriend rises to her defense, and before you know it the poor journalist is being used as a punching bag until, pow, here comes Nong-Toom kicking these thugs into submission and landing squarely on her high heel spikes. Such gynandrous exaggerations prove thrilling!!

It's hard not to like this movie. It's balanced so well between truth and prurience. It certainly seems to confirm Variety reviewer Russell Edwards' suspicion that Thailand is trying to "corner the market in gay-themed sports movies" and his projection that it "should K.O. predisposed auds, providing modest niche B.O." Without a doubt. But his further honesty in stating the film is "sweetly entertaining but bland" warns that, where it caters to a beautiful surface, it eschews the depths that could have made this a profound examination of cultural attitudes towards gender as well as internalized gender conflict. Everything is made so easy for Nong Toom to become the woman he wishes to be that the dramatic tension of his quest is weakened, much like the hormone pills that weakened his virility.

That weakened tension, however, is reinforced by the cameo appearance of Nong Toom herself in the final scenes of the movie, where she appears on a palanquin supported by several muscled men and offers sweet advice to a young kickboxer who has been forced to wear make-up to entertain her. She wipes off his lipstick and tells him to fight from his heart.

This, I would say, is the aspect of the movie that I found most powerful. When Nong Toom is a boy and sent away to the monastery, he sneaks out to work for a living to support a crippled father and an interred mother. When he can no longer find work to support his parents, he sits on some steps to cry. He is spotted by a transvestite who feeds him, finds him work, helps care for his parents, guides him to a wandering monk for further training, and shows him that his dream is accessible, that he can be like her if he wishes. That later in the film he then offers the same assistance to a young boy connotes the subcultural continuity that has helped so many gender-variant men and women to survive in a world where parents often forsake them, schools miseducate them, and governments punish them for aspiring towards the love and union given to other citizens.

Too often criticism is aimed at older men or women who take a youngster underwing. Sexual irresponsibility is more often than not projected upon them, when in truth what is more truthfully going on is a process of acculturation into a subculture whereby such a fragile spirit in such a young body can survive. This is one of the first foreign films where I have seen the continuity of this tradition so tenderly depicted.

It also deserves praise for joining ranks with cinematic depictions of gender variant individuals who fight for themselves—in this film literally—proving they are not victims, despite those who would wish to make them so in order to retain the comfort of their own narrow identities.

And it promises to each individual the wealth of their own sovereignty and their own self-expression, wherever it lies on the vast continuum of gender expression. In the final scenes where the real Nong Toom is shown at her vanity with actor Suwan stepping away into the background, we have a momentary sense of the internalized gender conflict that could have enrichened this movie even further. You no longer need me, the kickboxer smiles, you have become who you wanted to be, achieved what you wanted to achieve. But even so, she doesn't quite want to let go of this muscular young man who fought for himself. You don't have to, he reminds her, I will always be within you. The true and beautiful sygyzy.

And it promises to each individual the wealth of their own sovereignty and their own self-expression, wherever it lies on the vast continuum of gender expression. In the final scenes where the real Nong Toom is shown at her vanity with actor Suwan stepping away into the background, we have a momentary sense of the internalized gender conflict that could have enrichened this movie even further. You no longer need me, the kickboxer smiles, you have become who you wanted to be, achieved what you wanted to achieve. But even so, she doesn't quite want to let go of this muscular young man who fought for himself. You don't have to, he reminds her, I will always be within you. The true and beautiful sygyzy.Then I had a second opportunity to see Beautiful Boxer at an advance screening of its theatrical distribution in January 2005. I wrote then:

Attended a Film Society screening of Beautiful Boxer at the Lumiere with director Uekrongtham, actor Asanee Suwan and the film's subject Nong Toom, in attendance to promote the launch of the film's U.S. distribution. It was one of those singularly unique cinematic evenings in San Francisco that challenges my intellect even as it invigorates my soul.

Coincidentally, earlier in the afternoon while perusing the Intersections website, I came across an essay by Graeme Storer entitled "Performing Sexual Identity: Naming and Resisting 'Gayness' in Modern Thailand" in which Storer credited Parinya's appearance in the kickboxing arena as one of two critical events that has helped to shape Thai understanding of gender and sexuality. Storer's essay greatly enhanced my second viewing of Beautiful Boxer and provided a cultural context that underscored the film's themes with added resonance and depth. Further, I would suggest that, within the parameters of the contemporary Thai understanding of gender variance, the distribution of Beautiful Boxer in the United States and, more importantly, the appearance of Parinya at last night's screening was in and of itself its own critical event for Western queer-identified individuals.

Storer asserts that there is no indigenous Thai noun for a "homosexual" person other than kathoey and that like his Filipino or Indonesian counterpart (the bakla or waria respectively), the Thai kathoey "is feminised with unspoken but strict rules governing his behavior. Thus the male kathoey is expected to adopt traditional forms of address reserved for women . . . , dress in female clothing, and generally perform femininity. Kathoey are sometimes referred to in Thai as . . . the 'second type of women.' "

"The ubiquitous presence of the kathoey in Thailand," Storer continues, "might suggest, at first glance, a challenge to the traditional patriarchal gender system. But as Peter Jackson notes, the kathoey, in enacting femininity in feminine spaces, reinforces the gender system. Further, while the kathoey have access to the female domain, the naming of kathoey as 'second type of woman' firmly relegates them into an inferior position within that domain. Thus, even though kathoey are readily visible in Thai society, the term remains marked and problematised and nowadays, is often used in a derogatory way . . . ."

It is remarkable to consider that when Parinya became visible as a kickboxer, she was only 16 years old. Although it appears that it was financial concerns that drove her into the ring, such necessity engendered a form of protest that had never before been seen in Thailand. "[T]he appearance of Parinya in the boxing ring, performing kathoey (sporting external signs of femininity at least) but demanding room in a male space clearly troubled normative gender boundaries. Boxing is a game for men and real men do not wear lipstick."

So the true triumph of Parinya was to perform two gendered roles that until then had been considered intrinsic and essential. Not only was she a "real man" who could kickbox but she was a kathoey who eventually elected to surgically alter her sex to become a woman.

Viewing her in front of the screening audience, I was struck by how beautiful she truly was, but, after watching the film, had to recognize within myself that I preferred her as a young male. It is the first time that I, performing my own sexuality as a gay male, realized the tension I experience in the presence of transsexuals. The director himself admitted that he did not have a favorable impression of Parinya when he approached her about doing the film. Her choice to be a kathoey and to become a transsexual seems, as stated above, less transgressive than it sounds. To become a "second type of woman" within a system that denigrates women strikes me as a giant step backwards. But, of course, the truth is that we each choose (or at least many of us choose) the performance of gender and sexuality that feels right for each of us. And, obviously, just because some men think women are beneath them does not mean they are. We each in our own way fight against that monolithic misconception.

My concern is that, as good as the movie makes you feel for witnessing one individual's determination to become who s/he feels s/he must be, something everyone can salute and identify with, it is somehow culturally inappropriate to embrace it as "gay"; an issue I also have with how the relationship in Tropical Malady is being interpreted. These are not "gay" experiences; they are something culturally different and deserve the space to be so. For anyone interested in these issues, Beautiful Boxer will not disappoint. I believe it opens Friday here in the Bay Area and I hope the local queer community along with all those unfortunate to not be queer

My concern is that, as good as the movie makes you feel for witnessing one individual's determination to become who s/he feels s/he must be, something everyone can salute and identify with, it is somehow culturally inappropriate to embrace it as "gay"; an issue I also have with how the relationship in Tropical Malady is being interpreted. These are not "gay" experiences; they are something culturally different and deserve the space to be so. For anyone interested in these issues, Beautiful Boxer will not disappoint. I believe it opens Friday here in the Bay Area and I hope the local queer community along with all those unfortunate to not be queer Graeme Storer's essay is much more insightful and articulate than I am. Please give it a read, if only to enhance your appreciation of Beautiful Boxer:

Now with the DVD release of Beautiful Boxer I am looking forward to whatever additional materials might be included on the disc.

08/21/06 UPDATE: Peter Nellhaus, anticipating his own sojourn to Thailand, reviews Beautiful Boxer for