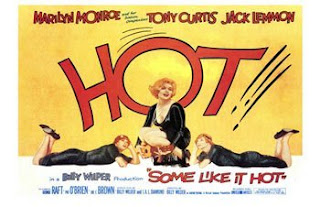

Following the PFA screening of Billy Wilder's Some Like It Hot, in conjunction with the "Thousand Decisions in the Dark" series, David Thomson returned to converse with his audience. He was pleased that they enjoyed Some Like It Hot, which he considered Wilder's peak. The next film Wilder made was The Apartment, which won virtually everything, including Best Picture. Some Like It Hot, on the other hand, won one Oscar for costumes, though Wilder was nominated, as was the script, and Lemmon's performance. Thomson suspects there was a degree to which the film was a bit racey for the times. People loved it but were a little bit confused by it and puzzled over why they liked it so much. They certainly didn't think it was the kind of film for that period to bring up in front of the Oscars in a big way although, of course, people who devote themselves to comedy—and there aren't as many of them around as there were then—say they get very badly treated by the Oscars. They would say that comedy is a genre that America has done best, that it did first, and that there's been a notion in the Academy that to win the prizes you have to be serious and dramatic. Maybe nothing is more serious than making people laugh. It reminds Thomson of the moment in Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels (1941) where a director, played by Joel McCrea, who has been churning out comedy hits, suddenly gets prestige conscious and wants to make a film called O Brother, Where Art Thou?; about the common man in the world. He gets much too big a dose of the really hard life that the common man has and he ends up on a Georgia chain gang. They take him to a church one Sunday night and there's a movie show (a Mickey Mouse cartoon) which he stops to watch. Of course it restores his faith in the comedy "crap" that he was doing.

When we talk about the genres in Hollywood, there's no loss greater than the loss of the screwball comedy. Some Like It Hot is a screwball comedy actually; that's the category you have to put it in. The energy takes over at a certain point and you're prepared to let character go, if you don't mind that the characters are not quite as true as they might be because the energy's driving the film forward. Although Some Like It Hot seemed very advanced for its time—and it was in terms of the gender confusion, more advanced than audiences were actually ready for in 1959—maybe it was the last screwball comedy as well and, in that sense, a throwback even then.

Thomson opened up to questions so I offered my appreciation of his highlighting the tossing of the coin bit. It reminded me of the famous press conference with James Cagney at Sardi's where he was asked which gangsters he modeled his characters after. Cagney was quick to correct that the gangsters imitated him, not the other way around. Some Like It Hot is brilliant in its cinematic performativity, citing classic performances that remain recognizable today. Did you notice, Thomson responded, I think it was just after that when they sit down at the banquet and one of the stooges says "I was at Rigoletto's" where Raft picks up a grapefruit in tribute to Cagney's scene from The Public Enemy (1931) where he shoves the grapefruit in Mae Clark's face? But now here's the little extra, Thomson beamed, does anyone know who was tossing the coin? One fellow guessed correctly that it was Edward G. Robinson's son who, Thomson thinks, never made another film, though he was well-known to "the guys."

One fellow noted that Thomson observed and his audience duly recognized how Some Like It Hot was ahead of its time, unquestionably daring. He wondered if Thomson knew of any ill reactions to Wilder's daring examination of gender? Thomson excused himself by saying he was not living in America at the time and that, in fact, he was living in a country where it was still illegal to have homosexual relationships, though of course in many states in this country it remains illegal. Homosexuality was a huge issue in Britain. As far as he knew, however, in this country the League of Decency condemned Some Like It Hot but they tended to condemn a lot of films. By 1959 the censorship code was breaking up. If you follow films year by year during this period you'll see how each year they allow just a little bit more. For instance, the one thing he recalls being commented upon was that in the last musical number where Marilyn sings "I'm Through With Love", she's sitting on the piano wearing a dress that is sheer and revealing. By today's standards it hardly matters and, truth be known, what you can see is just how overweight she was; but, Thomson does remember that at the time Monroe's dress bordered on the scandalous and there was concern over whether you could see her nipples. Around the same time there was a Jayne Mansfield vehicle called Too Hot To Handle (1960), which is dead and deserves to be dead, but required people having to paint sparkle on the print because Mansfield's nipples were revealed in a few frames. Her great big nipples loomed up and had to be painted out. Censorship is usually lunatic and certainly if you describe it in hindsight, it sounds ridiculous; but, that was taken very seriously. The general reaction to Some Like It Hot in the U.S., as well as Britain, was that it was a pretty straight, heterosexual film. The question was whether Marilyn was showing too much, or if one or two of her lines had too obvious a double meaning, and not whether there was a homosexual agenda. People at that time didn't think too hard about Jack Lemmon's ecstasy when he's playing with the maracas, which is a fabulous scene because you have the feeling that this slightly unstable person is slipping. Let alone the ending where Joe E. Brown quips, "Nobody's perfect." Everybody laughed at it but without much awareness of why they were laughing; a very strange phenomenon.

One fellow admitted to being old enough that he watched Uncle Miltie in drag on television. Milton Berle's t.v. show was quite popular just a few years before Some Like It Hot. At the time it was considered wholesome fun and, oddly enough, reinforced heterosexist stereotypes. A guy with arched eyebrows wearing drag was easily laughed at as a foil for "true" masculinity. Drag was even bigger in Britain than the U.S., Thomson concurred. There are several comedians who shaped their career doing drag in their routines. With regard to the jokes at Marilyn's expense, this fellow agreed that this might have been what Hollywood thought they were doing to her though he felt Marilyn transcended those attempts. Even as an 8-year-old, he could detect Marilyn's vulnerable sweetness, which he couldn't help relating to. She came off endearing and the dirty innuendoes slipped off her performance. The tragedy of Monroe, Thomson reminded, was that everyone thought, "Well, she's going to live so much longer and we'll have a chance to make a different life with her, a new life with her." The tragedy that she sometimes clumsily alluded to in her life was a real thing. She's a haunting figure now. She photographs so extraordinarily. That's the thing. When photographers tell you that there are some people who just photograph well and it doesn't matter really. In the end I think that's what Wilder would have said. She's a pain in the neck to work with and she certainly pushed the budget of the film up due to the delays but what you get is something that no one else could give you. Recently, for some other purpose, Thomson was looking at an old film with Clara Bow, who was essentially a silent screen actress. Bow had dark hair but she had a bit of Monroe's look, she had that sauciness, but Clara Bow was much smarter than Monroe. Some people have said that Monroe is acting stupid, but that she's not really stupid; but, Thomson isn't so sure. She certainly had a childlike quality about her that does, as the fellow mentioned, make Monroe endearing.

By contrast, the two guys played by Curtis and Lemmon really are heels. They're played flat out as heels. Those were the male leads that Wilder was good at, like Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity, like Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend, like William Holden in Sunset Boulevard, like Kirk Douglas in Ace in the Hole. Wilder was wonderful at capturing sleazy, dishonest charmers, that kind of scoundrel peculiar to the enterprising American culture.

As for the demise of the screwball comedy, Thomson ventures that some people felt it was because audiences couldn't keep up the pace. There's something to be said about audiences becoming dumber and slowing down as television took hold. If you look at some of the great comedies of the '30s like My Man Godfrey (1936) or The Awful Truth (1937), they are so quick. Kids today have a hard time keeping up with such repartee. They pushed, they filled their 90 minutes in a way that we have lost. People don't write that way anymore. Wilder, you see, was a writer before he was a director. Wilder with Charles Brackett, and occasionally with other people, wrote films like Ninotchka (1939), Midnight (1939), Ball of Fire (1941), terrific comedies. Wilder was writing for 10 years before he really got a break as a director. He always knew he wanted to direct. He always knew that was where the power was. Wilder was a bit of a hustler. There's no question. He was a tough competitor. He pushed people out of jobs and got himself into jobs.

Wilder was very good at still action. For instance, the passage where he crosscuts from Monroe and Curtis on the yacht to Lemmon and Brown dancing the tango, the action within those frames is not too elaborate but Wilder was very good at that kind of thing. When the film goes slapstick, a lot of action and chase, Thomson doesn't think Wilder was as interested in those scenes. He probably liked to get to the talk scenes whereas a lot of comedic genius, from Buster Keaton to Jerry Lewis, loved the action scene because that's where they really did their stuff. Wilder was a verbal comedian. His films wouldn't have been possible as silent films. He has to have talk and fairly smart talk at that.

As for why Americans have become less comedically literate over time, Thomson has no sure answers. It's an issue he finds perplexing. If he were to name his top ten films of all time, half of them would be comedies. Comedies last the best and they say the most. They're like songwriting. Thomson recalled growing up in Britain in the '30s and '40s listening to the American songbook. Those songs were great. Thomson doesn't want to sound or come across as an old fogie, though he's aware several think he's perfectly cast for the role, but no one's doing those songs anymore. No one's telling those wonderful jokes anymore either. Partly, he suspects, it's because the jokes have become very dark. This is a reflection of our times. Some of the great comics of recent times, like Richard Pryor, are people speaking out of great agony who have had to push the envelope, who have had to get through that experience of pain. The lyricism of comedy, the sheer fun of it, is harder. You look at Keaton and Chaplin too—although Chaplin always has ulterior motives—Laurel & Hardy, they just wanted to give us a good time. Thomson suggests that Jim Carrey is a comedian of near genius but he won't settle for just giving you a good time; he has to do something else with it. These days comedy has to come loaded down with some seriousness. At Telluride last year there was a wonderful screening of Jacques Tati's Play Time (1967) in a 70mm print and Tati's sheer genius of moving people around in and out of disastrous comic situations was breathtaking. It made you think that no one does that anymore. It used to be a key element. Thomson suggests that perhaps we—as a moviegoing public—don't like ourselves as much as we once did. A lot of our art and culture at the moment has much to do with our shared disappointment in what human beings have done. The innocence of comedies past is difficult to get to. Thomson still believes someone can come along and do it and he always hopes somebody will, but historically, if you look at film and the way genres have come and gone, the dying out of romantic and screwball comedies is a remarkable development.

Referencing back to Thomson's suspicion that television had something to do with the dumbing down of comic literacy among American audiences, I suggested that the laugh track was a mechanism that had a serious effect upon comedy's facility for pulling you into the joke. With the advent of the laugh track, audiences were guided through humor and denied a certain access of direct engagement. Audiences lost their own ability to determine comedy. They became reliant upon the canned laughter of others. Thomson said my point was sound. You could write a great book about the laugh track and how evil it is, he suggested. And yet, Thomson countered, this is not to say that television didn't produce some clowns of genius. Lucille Ball never made it in the movies really. On television she became a phenomenon and, by no means, the only one. So it's not clear cut.

Another fellow wondered if it was also partly due to the fact that all bets are off now. Comedians can do anything so they fall back on scatological references and broad sexual humor whereas before they had to be more subtle and nuanced. It's easier to get a cheap laugh these days, which has taken the literacy out of comedy. Thomson concurred that you could argue such a case, as well as arguing a similar case that the advent of liberty onscreen and the treatment of sex actually has had a good deal to do with killing romanticism. Sometimes under intense censorship, cinema can be pretty adult. There were people who could write situations so that you knew exactly what had happened. You had no doubts. Once more, people behaved responsibly in those situations. For example, there was a greater, natural feminism in America in the '30s than there was in any other decade.

Yet another guy wondered if the median age of the moviegoing public has changed over the years and if possibly the humor to a 25-year-old is no longer humorous to a 55-year-old. Thomson concurred that the average age of moviegoers has certainly become younger though these kids are smarter and smarter about what they're seeing, if not as spontaneous. Interestingly enough, you can show young kids slapstick from the '30s and they still love it. It's as they grow older that they find that kind of slapstick silly but if you show it to them early enough, they love it. There's something elemental about it. The other thing is that we're talking about an age and a kind of film inhabited by people like Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, Jack Lemmon, who all would have said they were actors, not comedians; comic actors perhaps, but actors. They took their characters very seriously.

Finally, with regard to the famous last line of Some Like It Hot, there was a way in which the movies of the 40 years before this film was made had been based on the assumption that, yes, people are perfect, or can be perfectible. There was a common code and the happy ending was a part of it; that love would conquer was a part of it. We have since grown up. We know that the common code is not common and is not a code. We know it was only a set of hopes that look increasingly naïve sometimes. But it would be hard to find a film that—at its very end—makes such a tremendous admission about imperfection and sort of sends people away cheering. But as he mentioned before, Thomson doesn't believe Wilder knew exactly what he meant by it.