Composer Miklós Rózsa would have been 100 years old on April 18, 2007. Culminating a year's worth of centenary tributes, San Francisco's Castro Theatre initiated the first Miklós Rózsa film festival held in the United States, including his Oscar wins Spellbound and Ben-Hur.

Composer Miklós Rózsa would have been 100 years old on April 18, 2007. Culminating a year's worth of centenary tributes, San Francisco's Castro Theatre initiated the first Miklós Rózsa film festival held in the United States, including his Oscar wins Spellbound and Ben-Hur.As the Castro program emphasizes: "With a definitive, powerful, and unmistakably individual style, [Miklós] Rózsa's passion and culture offer an exciting intensity to the medium of film. He virtually created the classic sound of 1940s film noir, and was the acknowledged master of the historical epic. As a brilliant composer for the concert hall, he represented a symphonic bridge between classical and film music, sharing his great talent with lovers of music on both sides of the artistic spectrum."

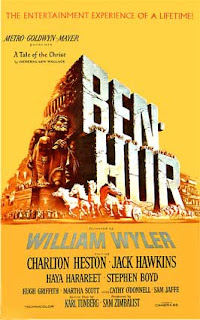

I attended the screening of William Wyler's Ben-Hur (1959), for which Miklós Rózsa received his third Academy Award. Out from Philadelphia to moderate the event was award-winning writer and film historian Steve Vertlieb, who began the program by providing a biography of Rózsa: "It has been said that cinema is the purest visual poetry. If the director supplies the canvas on which his imagery will be realized, then the composer lovingly paints the layered textures of the cinematic palette, bringing the subtle nuances of combined creation and imagination to life. If music is heaven's verse, then Miklós Rózsa was, perhaps, cinema's most eloquent poet, creating and composing 110 motion picture scores between 1937 and 1982, winning 16 Oscar nominations and 3 Oscars for best score of the year.

I attended the screening of William Wyler's Ben-Hur (1959), for which Miklós Rózsa received his third Academy Award. Out from Philadelphia to moderate the event was award-winning writer and film historian Steve Vertlieb, who began the program by providing a biography of Rózsa: "It has been said that cinema is the purest visual poetry. If the director supplies the canvas on which his imagery will be realized, then the composer lovingly paints the layered textures of the cinematic palette, bringing the subtle nuances of combined creation and imagination to life. If music is heaven's verse, then Miklós Rózsa was, perhaps, cinema's most eloquent poet, creating and composing 110 motion picture scores between 1937 and 1982, winning 16 Oscar nominations and 3 Oscars for best score of the year. "Miklós Rózsa was a cultured Hungarian-born composer who fell in love with this country during the filming of Alexander Korda's production of The Thief of Bagdad when the filming of the epic fantasy shifted to the Grand Canyon in 1940 due to war in Europe. The entire cast and crew left England to complete the shooting of the picture in America. Miklós Rózsa remained here after filming had concluded, settling in Hollywood and created some of the most haunting, passionate and unforgettable musical accompaniments ever written for a film."

"Miklós Rózsa was a cultured Hungarian-born composer who fell in love with this country during the filming of Alexander Korda's production of The Thief of Bagdad when the filming of the epic fantasy shifted to the Grand Canyon in 1940 due to war in Europe. The entire cast and crew left England to complete the shooting of the picture in America. Miklós Rózsa remained here after filming had concluded, settling in Hollywood and created some of the most haunting, passionate and unforgettable musical accompaniments ever written for a film."Among the tributes that Steve Vertlieb received and was asked to present was one by author Ray Bradbury who "adored" Miklós Rózsa. Bradbury wrote the narration spoken by Orson Welles in the King of Kings, just one of the many great films scored by Rózsa. For the recording sessions, before Orson Welles came to do his bit, Ray Bradbury himself came to the recording stage and, for timing purposes, actually spoke the narration while Rózsa conducted the orchestra.

Vertlieb read Bradbury's tribute to the Castro audience and the Rózsa family members on stage: "In all my life I've never had a more complete relationship with a composer than with Miklós Rózsa. When MGM asked me to write the narration for King of Kings, I immediately joined a partnership with Margaret Booth, the film editor, and we became fast friends. The most wonderful moment in my life was when I went on the sound stage to watch Miklós Rózsa conduct the score for King of Kings and then heard my own voice booming out over the orchestra and dear Miklós' head as I spoke the narration. I wish that I had a recording today of my voice with his music because it became a partnership and a great friendship for life. To everyone hearing his wonderful music this week, I send my love and regard to the memory of Miklós Rózsa."

Vertlieb read Bradbury's tribute to the Castro audience and the Rózsa family members on stage: "In all my life I've never had a more complete relationship with a composer than with Miklós Rózsa. When MGM asked me to write the narration for King of Kings, I immediately joined a partnership with Margaret Booth, the film editor, and we became fast friends. The most wonderful moment in my life was when I went on the sound stage to watch Miklós Rózsa conduct the score for King of Kings and then heard my own voice booming out over the orchestra and dear Miklós' head as I spoke the narration. I wish that I had a recording today of my voice with his music because it became a partnership and a great friendship for life. To everyone hearing his wonderful music this week, I send my love and regard to the memory of Miklós Rózsa."Vertlieb likewise presented and read aloud the official proclamation from the Ambassador of Hungary and the Hungarian Embassy in Washington, D.C.: "On behalf of the grateful people of Hungary on the centennial of his birth, let me express the pride and pleasure we take in commemorating the life and work of Miklós Rózsa. This distinguished composer and native Hungarian brought pride and recognition to his people through the art and artistry of his talent, giving noble voice through the medium of motion pictures and on the concert stage to the rich legacy and firm tradition of Hungarian culture. In a musical career spanning 60 years Miklós Rózsa received honor for his people and recognition by his peers, winning three richly-deserved Academy Awards and 16 Oscar nominations from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his significant contribution to the sound of movies. In joyous tribute to both the man and his music, we join Miklós Rózsa's family and his millions of admirers around the world in presenting this proclamation from the Hungarian people honoring one of our greatest composers on the occasion of his 100th birthday and the first comprehensive film festival ever held in the United States initiated and presented by San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre honoring his wondrous and enduring musical legacy."

Seán Martinfield, the Fine Arts critic for The San Francisco Sentinel, likewise represented Mayor Newsom's office in presenting an equally fullblown proclamation from the City of San Francisco.

Vertlieb then conducted an onstage interview with Rózsa's daughter Juliet, starting off by asking her what were her most vivid memories of her father. After thanking everyone involved in the year-long tribute to her father's legacy, Juliet recalled—within the context of the screening of Ben-Hur—that she and her brother were put in a school in Switzerland for a few months while the film was being shot in Europe. Their father then picked them up and drove them to Rome to visit the arena where the chariot race had been filmed. It was an amazing, haunting sight for her, with the huge statues looming over the abandoned track. She likewise attended some of her father's recording sessions in Rome where, ruefully, she recounted her father's issues with the Italian orchestra whose musicians he felt were "like children". They didn't seem to take the recording seriously. When he would raise his baton to start, there would still be musicians drinking Cokes and talking.

Vertlieb, a friend of Rózsa's for nearly 27 years, recalled a similar circumstance during the recording of the soundtrack for Ray Harryhausen's The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. Rózsa complained at that time as well that the orchestra members were "lackadaisical" and didn't seem committed to rehearsal. Rózsa recounted to Vertlieb that one musician in the back row was reading a newspaper. He chastised the orchestra, "You all speak about religion and say that you're very religious. Well, music is our religion and you have to take it seriously." Unfortunately, the orchestra was thin and Vertlieb recalled that Harryhausen's co-producer Charles Schneer was a notorious penny-pincher who stood there during the recording sessions with a stopwatch. Whenever Rózsa wanted to do another take, Schneer would say, "No, no, no. That's good enough. Let's move on." This was, of course, a source of great frustration for Rózsa. Despite this, Ray Harryhausen adored Rózsa and they had a great working relationship.

Vertlieb, a friend of Rózsa's for nearly 27 years, recalled a similar circumstance during the recording of the soundtrack for Ray Harryhausen's The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. Rózsa complained at that time as well that the orchestra members were "lackadaisical" and didn't seem committed to rehearsal. Rózsa recounted to Vertlieb that one musician in the back row was reading a newspaper. He chastised the orchestra, "You all speak about religion and say that you're very religious. Well, music is our religion and you have to take it seriously." Unfortunately, the orchestra was thin and Vertlieb recalled that Harryhausen's co-producer Charles Schneer was a notorious penny-pincher who stood there during the recording sessions with a stopwatch. Whenever Rózsa wanted to do another take, Schneer would say, "No, no, no. That's good enough. Let's move on." This was, of course, a source of great frustration for Rózsa. Despite this, Ray Harryhausen adored Rózsa and they had a great working relationship.Asked to characterize her father, Juliet remembered him "as a very European man, generous and humble." He traveled a lot. One of her most cherished memories was when she was 4-5 and allowed to listen to her father composing at home on his piano, which his contract with MGM allowed. Though his children were not permitted to be in the room while their father was working, she would nonetheless creep up the stairs, sneak quietly into the room and lie beside the family's pet boxer Mowgli underneath the piano. Her father would always find her and ask her to leave. She couldn't understand why she had to leave and Mowgli got to stay. A few hours would go by and the whole thing would go again with her creeping up the stairs and sneaking into the room underneath the piano with Mowgli, being found and asked to leave again. The house was always filled with music. Bizarrely, even when he wasn't home, she could hear his music throughout the house.

She knew even as she was growing up that her father was different than other fathers; that he was special. Already being traditional Europeans, their family did not grow up like other American families. They didn't eat hot dogs and hamburgers. They didn't go to baseball games. When he had free time, her father would take her to the local museum or to a concert. At school the other kids would ask her, "What does your daddy do?" and she would reply, "My daddy plays the piano." It didn't take her long to realize that most daddies don't play the piano. At a very young age she realized they had someone special in the house.

Her father entertained a lot. When she was a teenager, she was delegated to be the official door opener and coat taker. Most of his guests were musicians and directors, occasionally actors—Joseph Cotten, James Mason, and Cameron Mitchell (with whom he was very close)—but mainly musicians: cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, violinist Jascha Heifetz, conductor Eugene Ormandy. "You always heard different languages."

Among her personal favorites of her father's oeuvre, The Killers ranks high because of its main theme, which was later woven into the Dragnet franchise. Vertlieb mentioned the infamous litigation over Walter Schumann's adaptation of The Killers theme for Dragnet, which Miklós Rózsa won in court. Whether Schumann's plagiarism was unconscious or subliminal, Vertlieb noted that in the 1987 spoof of Dragnet with Dan Aykroyd, credit for the theme was assigned to both Rózsa and Schumann.

Among her personal favorites of her father's oeuvre, The Killers ranks high because of its main theme, which was later woven into the Dragnet franchise. Vertlieb mentioned the infamous litigation over Walter Schumann's adaptation of The Killers theme for Dragnet, which Miklós Rózsa won in court. Whether Schumann's plagiarism was unconscious or subliminal, Vertlieb noted that in the 1987 spoof of Dragnet with Dan Aykroyd, credit for the theme was assigned to both Rózsa and Schumann. Juliet offered her affection for the waltz scene in Madame Bovary as well. She felt her father's score for that film caught the frenzy and passion of the time.

Juliet offered her affection for the waltz scene in Madame Bovary as well. She felt her father's score for that film caught the frenzy and passion of the time.Juliet is convinced her father would have been overwhelmed by the year-long tribute celebrating the centenary of his birth. There have been several new recordings of his movie scores (The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Spellbound), as well as his orchestral pieces. A new recording of his violin concerto is, in fact, nominated for a Grammy and—of course—the yearlong tribute has culminated in the Castro film retrospective.

Of the 110 film scores that he composed, Juliet suspects that Ben-Hur was Rózsa's favorite. He worked on it the longest, almost a year, and was close to the film. Rather than having the film finished and presented to him, he worked on set with director William Wyler.

Though Rózsa won his first Oscar for Alfred Hitchock's Spellbound, he never again worked with Hitchcock, which Juliet doesn't believe her father regretted. As he was working on Spellbound, Rózsa and Hitchcock exchanged few words. Rózsa remained autonomous. Even when Rózsa won his Oscar, Hitchcock said nothing. "He didn't feel he was missing anything by not working with Hitchcock again."

Though Rózsa won his first Oscar for Alfred Hitchock's Spellbound, he never again worked with Hitchcock, which Juliet doesn't believe her father regretted. As he was working on Spellbound, Rózsa and Hitchcock exchanged few words. Rózsa remained autonomous. Even when Rózsa won his Oscar, Hitchcock said nothing. "He didn't feel he was missing anything by not working with Hitchcock again." Bernard Hermann—who came to be associated with Hitchcock rather than Rózsa—expressed disappointment when MGM granted Rózsa the contract to score Julius Caesar instead of him, particularly since John Houseman—who was a close friend of Hermann's—produced Julius Caesar. Interestingly, many years later and despite his expressed disappointment, when Hermann compiled and recorded music for the great Shakespearean films, he included Rózsa's overture for Julius Caesar. Juliet recalled that, at the time, her father was a bit surprised by Hermann's concession but emphasized that he and "Benny" Hermann were extremely close friends. Even though Hermann was disappointed with the decision on Julius Caesar, he never held Rózsa responsible; he understood it was a studio decision.

Bernard Hermann—who came to be associated with Hitchcock rather than Rózsa—expressed disappointment when MGM granted Rózsa the contract to score Julius Caesar instead of him, particularly since John Houseman—who was a close friend of Hermann's—produced Julius Caesar. Interestingly, many years later and despite his expressed disappointment, when Hermann compiled and recorded music for the great Shakespearean films, he included Rózsa's overture for Julius Caesar. Juliet recalled that, at the time, her father was a bit surprised by Hermann's concession but emphasized that he and "Benny" Hermann were extremely close friends. Even though Hermann was disappointed with the decision on Julius Caesar, he never held Rózsa responsible; he understood it was a studio decision.Agreeing with Vertlieb that the score to Ben-Hur was one of her father's most consummate, Juliet recalled that at her father's funeral members of the Hollywood Bowl played the "Parade of the Charioteers."

Cross-published on Twitch.

01/03/08 UPDATE: I received a kind email from Steve Vertlieb: "Dear Michael, I wanted to thank you sincerely for your lovely, thoughtful comments regarding our Miklos Rozsa film festival at San Francisco's Castro Theatre. Your eloquent appreciation of our efforts meant a great deal, both to the Rozsa family, and to myself. I wish I had known that you were in the audience last Saturday evening. I would like to have had an opportunity to say hello on a more personal level. Please do drop a line or two, should you have either the inclination or opportunity."

01/20/08 UPDATE: Andrew Mangravite provides an overview of Rózsa's contributions to the film noir genre in his essay "He Made Film Noir Sing."