When I first announced that San Francisco's C.G. Jung Institute was offering a one-day seminar with Dr. John Beebe on Cinematic Expressions of the Anima: A Day With the Feminine in Film, I replicated the program brochure. In gist, Dr. Beebe selected Guy Maddin's Heart of the World and Jean Vigo's L'Atalante to be shown together. "Both are recognized film classics possessed of abundant charm, humor, poignancy, and vitality and cherished by connoisseurs; yet since their first release neither has reached a mainstream audience. This is because they challenge conventions of narrative cinema to make room for an expression of the unconscious. They privilege the image over narrative, and they complicate the masculine hero myth with another archetypal pattern, the realization and revaluation of the feminine. Both have strikingly original soundtracks, and both draw anachronistically on silent film techniques. Both are unusually short for the archetypal ground they cover."

When I first announced that San Francisco's C.G. Jung Institute was offering a one-day seminar with Dr. John Beebe on Cinematic Expressions of the Anima: A Day With the Feminine in Film, I replicated the program brochure. In gist, Dr. Beebe selected Guy Maddin's Heart of the World and Jean Vigo's L'Atalante to be shown together. "Both are recognized film classics possessed of abundant charm, humor, poignancy, and vitality and cherished by connoisseurs; yet since their first release neither has reached a mainstream audience. This is because they challenge conventions of narrative cinema to make room for an expression of the unconscious. They privilege the image over narrative, and they complicate the masculine hero myth with another archetypal pattern, the realization and revaluation of the feminine. Both have strikingly original soundtracks, and both draw anachronistically on silent film techniques. Both are unusually short for the archetypal ground they cover."Dr. Beebe's approach—after showing each film in full—was to "lead the participants in a discussion of the psychological implications of its imagery, demonstrating what it has to tell us about the role of the feminine in ensouling and centering the self, and about masculine attitudes that block and enable the psyche's ability to manifest wholeness." I offer up my notes on the seminar with the caveat that my understanding of Jungian psychology is still on a learning curve after all these years and—should any of these ideas provoke interest—I strongly suggest my readers follow through with Dr. Beebe's upcoming volume The Presence of the Feminine in Film, co-authored by Virginia Apperson and soon to be released by Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung often said that work on confronting one's "shadow self" was the "apprentice piece"; whereas, confronting one's "anima" was the masterpiece. Shadow and anima are two of the main archetypes within Jung's theory of the collective unconscious. Both are psychological functions that generate projection. In the case of the shadow, an individual projects his own darkness upon others, which is a fairly straightforward concept; but, the role of the anima in individuation is in some ways tantalizingly more complex and not as easy to pin down. In general psychological parlance it is the inner personality that is turned towards the unconscious of the individual (contrasted with the "persona", which is the social façade) and—within its most popular understanding—retains a contrasexual element (i.e., it is a feminine principle especially present in men, much like the "animus" is a masculine principle present in women) that organizes the structures of the unconscious. I qualify that last statement because recent Jungian scholasticism has questioned the exactitude of the contrasexual equation. In his own practice, Dr. John Beebe has observed that the "anima" is not reserved just for men nor the "animus" for women; but, as averages go, he sees it as a 3:1 ratio.

Detailing how he came to use film as a fulcrum to teach Jungian theory, Dr. Beebe recounted his involvement with the Ghost Ranch seminars organized by Murray Stein and situated at the former ranch of artist Georgia O'Keefe. This was the first time that Beebe showed a film to a professional audience and it just so happened to be Jean Vigo's L'Atalante. But as the purpose of the Ghost Ranch seminars was to generate papers for publication so that Jungian theory could take academic shape, Beebe was forced to write up his presentation and, thus, his first essay on film. That paper "The Anima In Film" is available online in its entirety and is a great introductory read to the Jungian methodology Beebe developed to finesse film. As cinema is a projective medium, the anima's involvement seems obvious; but, even Dr. Beebe has tweaked the title of his first film essay, as well as his upcoming book, to designate that it's really not so much about the anima "in" film as it is about the anima "through" film. The director who creates a film is comparable to the self that creates a dream.

To introduce the thrust of his seminar, Dr. Beebe provided the nine qualities he has come to associate with the anima's presence in film. I quote from his essay:

1. Unusual radiance (e.g., Garbo, Monroe). Often the most amusing and gripping aspect of a movie is to watch ordinary actors or actresses (e.g., Melvyn Douglas and Ina Claire in Ninotchka) contend with a more mind-blowing presence—a star personality who seems to draw life from a source beyond the mundane (e.g., Garbo in the same film). This inner radiance is one sign of the anima—and it is why actresses asked to portray the anima so often are spoken of as stars and are chosen more for their uncanny presence, whether or not they are particularly good at naturalistic characterization.

1. Unusual radiance (e.g., Garbo, Monroe). Often the most amusing and gripping aspect of a movie is to watch ordinary actors or actresses (e.g., Melvyn Douglas and Ina Claire in Ninotchka) contend with a more mind-blowing presence—a star personality who seems to draw life from a source beyond the mundane (e.g., Garbo in the same film). This inner radiance is one sign of the anima—and it is why actresses asked to portray the anima so often are spoken of as stars and are chosen more for their uncanny presence, whether or not they are particularly good at naturalistic characterization. 2. A desire to make emotional connection as the main concern of the character. One of the ways to distinguish an actual woman is her need to be able to say "no," as part of the assertion of her own identity and being. (Part of the comedy of Katharine Hepburn is that she can usually only say no; so that when she finally says "yes," we know it stands as an affirmation of an independent woman's actual being.) By contrast, the anima figure wants to be loved, or occasionally to be hated, in either case living for connection, as is consistent with her general role as representative of the status of the man's unconscious eros and particularly his relationship to himself. (Ingrid Bergman, in Notorious, keeps asking Cary Grant, verbally and nonverbally, whether he loves her. We feel her hunger for connection and anticipate that she will come alive only if he says yes. His affect is frozen by cynicism and can only be redeemed by his acceptance of her need for connection.) [Dr. Beebe credited fellow Jungian analyst Beverly Zabriskie for this insight. She reacted to a screening of Gaslight where Beebe described Ingrid Bergman's character Paula Alquist Anton as a woman who comes alive when Charles Boyer's character Gregory Anton says yes to her love. Actually, Zabriskie countered, she's not a real woman. An actual woman would say "no" more than Paula does in order to define herself. That's when Beebe realized that the anima is not an actual woman.]

2. A desire to make emotional connection as the main concern of the character. One of the ways to distinguish an actual woman is her need to be able to say "no," as part of the assertion of her own identity and being. (Part of the comedy of Katharine Hepburn is that she can usually only say no; so that when she finally says "yes," we know it stands as an affirmation of an independent woman's actual being.) By contrast, the anima figure wants to be loved, or occasionally to be hated, in either case living for connection, as is consistent with her general role as representative of the status of the man's unconscious eros and particularly his relationship to himself. (Ingrid Bergman, in Notorious, keeps asking Cary Grant, verbally and nonverbally, whether he loves her. We feel her hunger for connection and anticipate that she will come alive only if he says yes. His affect is frozen by cynicism and can only be redeemed by his acceptance of her need for connection.) [Dr. Beebe credited fellow Jungian analyst Beverly Zabriskie for this insight. She reacted to a screening of Gaslight where Beebe described Ingrid Bergman's character Paula Alquist Anton as a woman who comes alive when Charles Boyer's character Gregory Anton says yes to her love. Actually, Zabriskie countered, she's not a real woman. An actual woman would say "no" more than Paula does in order to define herself. That's when Beebe realized that the anima is not an actual woman.]3. Having come from some, quite other, place into the midst of a reality more familiar to us than the character's own place of origin. (Audrey Hepburn, in Roman Holiday, is a princess visiting Rome who decides to escape briefly into the life a commoner might be able to enjoy on a first trip to that city.)

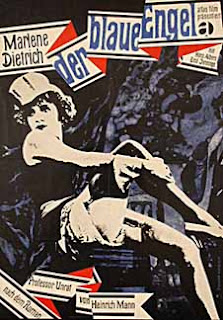

4. The character is the feminine mirror of traits we have already witnessed in the attitude or behavior of another, usually male, character. (Marlene Dietrich as a seductive carbaret singer performing before her audience in The Blue Angel displays the cold authoritarianism of the gymnasium professor of English, Emil Jannings, who manipulates the students' fear of him in the opening scene of the movie. Jannings pacing back and forth in front of his class and resting against his desk as he holds forth are mirrored in Dietrich's controlling stride and aggressive seated posture in front of her audience.) [This quality leans into the contrasexual understanding of the anima, which configures her as a contrasexual mirror. Beebe, in fact, once overheard one man explaining to the other, "Your anima is the woman you are." Dietrich's deployment of the archetype is furthered by her purposeful masculine attire, as if to draw the comparison tighter.]

4. The character is the feminine mirror of traits we have already witnessed in the attitude or behavior of another, usually male, character. (Marlene Dietrich as a seductive carbaret singer performing before her audience in The Blue Angel displays the cold authoritarianism of the gymnasium professor of English, Emil Jannings, who manipulates the students' fear of him in the opening scene of the movie. Jannings pacing back and forth in front of his class and resting against his desk as he holds forth are mirrored in Dietrich's controlling stride and aggressive seated posture in front of her audience.) [This quality leans into the contrasexual understanding of the anima, which configures her as a contrasexual mirror. Beebe, in fact, once overheard one man explaining to the other, "Your anima is the woman you are." Dietrich's deployment of the archetype is furthered by her purposeful masculine attire, as if to draw the comparison tighter.]5. The character has some unusual capacity for life, in vivid contrast to other characters in the film. (The one young woman in the office of stony bureaucrats in Ikiru is able to laugh at almost anything. When she meets her boss, Watanabe, just at the point that he has learned that he has advanced stomach cancer and is uninterested in eating anything, she has an unusual appetite for food and greedily devours all that he buys her.)

6. The character offers a piece of advice, frequently couched in the form of an almost unacceptable rebuke, which has the effect of changing another character's relation to a personal reality. (The young woman in Ikiru scorns Watanabe's depressed confession that he has wasted his life living for his son. Shortly after, still in her presence, Watanabe is suddenly enlightened to his life task, which will be to use the rest of his life living for children, this time by expediting the building of a playground that his own office, along with the other agencies of the city bureaucracy, has been stalling indefinitely with red tape. He finds his destiny and fulfillment in his own nature as a man who is meant to dedicate his life to the happiness of others, exactly within the pattern he established after his wife's death years before, of living for his son's development rather than to further himself. The anima figure rescues his authentic relationship to himself, which requires a tragic acceptance of this pattern as his individuation and his path to self-transcendence.) [Many years ago at an earlier seminar of Dr. Beebe's, I befriended Francis Lu, a therapist who had written an incisive article on Kurosawa's Ikiru and mailed it to me. Francis has since gone on to teach film at many Esalen retreats. It was many years before I finally saw Ikiru (which, appropriately, means "to live"), but I remembered his comments and Dr. Beebe concurs that it is one of the best treatments of the film. Another example of this quality would be The Consolation of Philosophy, written by Boethius while he was imprisoned awaiting execution. In that piece the anima arrives as Lady Philosophy. She consoles Boethius by discussing some rather unpleasant things that significantly alter his perception of the world.]

6. The character offers a piece of advice, frequently couched in the form of an almost unacceptable rebuke, which has the effect of changing another character's relation to a personal reality. (The young woman in Ikiru scorns Watanabe's depressed confession that he has wasted his life living for his son. Shortly after, still in her presence, Watanabe is suddenly enlightened to his life task, which will be to use the rest of his life living for children, this time by expediting the building of a playground that his own office, along with the other agencies of the city bureaucracy, has been stalling indefinitely with red tape. He finds his destiny and fulfillment in his own nature as a man who is meant to dedicate his life to the happiness of others, exactly within the pattern he established after his wife's death years before, of living for his son's development rather than to further himself. The anima figure rescues his authentic relationship to himself, which requires a tragic acceptance of this pattern as his individuation and his path to self-transcendence.) [Many years ago at an earlier seminar of Dr. Beebe's, I befriended Francis Lu, a therapist who had written an incisive article on Kurosawa's Ikiru and mailed it to me. Francis has since gone on to teach film at many Esalen retreats. It was many years before I finally saw Ikiru (which, appropriately, means "to live"), but I remembered his comments and Dr. Beebe concurs that it is one of the best treatments of the film. Another example of this quality would be The Consolation of Philosophy, written by Boethius while he was imprisoned awaiting execution. In that piece the anima arrives as Lady Philosophy. She consoles Boethius by discussing some rather unpleasant things that significantly alter his perception of the world.]7. The character exerts a protective and often therapeutic effect on someone else. (The young widow in Tender Mercies helps Robert Duvall overcome the alcoholism that has threatened his career.)

8. Less positively, the character leads another character to recognize a problem in personality which is insoluble. (In Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place, the antisocial screenwriter played by Humphrey Bogart meets an anima figure played—with a face to match the cool mask of his own—by Gloria Grahame, who cannot overcome her mounting doubts about him enough to accept him as a husband. Her failure to overcome her ambivalence is a precise indicator of the extent of the damage that exists in his relationship to himself.) [Beebe extolled Grahame as an actress who has not been fully given her due for expressing wit against patriarchy, as she likewise does in Fritz Lang's The Big Heat. Such wit mirrors the shadow of patriarchy. As someone who suffered in legal support for many years, I frequently commiserated with playwright Mike Black about how—if it weren't for the wisecracking examples of Eve Arden and Thelma Ritter—I would never have survived as a legal secretary. Lawyer's egoes were my training ground. Mike became inspired by this admission and wrote me a play called The Norma Desmond Strategem which accentuated this wisecracking strategy of survival, and which I performed at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. It was, needless to say, cathartic.]

8. Less positively, the character leads another character to recognize a problem in personality which is insoluble. (In Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place, the antisocial screenwriter played by Humphrey Bogart meets an anima figure played—with a face to match the cool mask of his own—by Gloria Grahame, who cannot overcome her mounting doubts about him enough to accept him as a husband. Her failure to overcome her ambivalence is a precise indicator of the extent of the damage that exists in his relationship to himself.) [Beebe extolled Grahame as an actress who has not been fully given her due for expressing wit against patriarchy, as she likewise does in Fritz Lang's The Big Heat. Such wit mirrors the shadow of patriarchy. As someone who suffered in legal support for many years, I frequently commiserated with playwright Mike Black about how—if it weren't for the wisecracking examples of Eve Arden and Thelma Ritter—I would never have survived as a legal secretary. Lawyer's egoes were my training ground. Mike became inspired by this admission and wrote me a play called The Norma Desmond Strategem which accentuated this wisecracking strategy of survival, and which I performed at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. It was, needless to say, cathartic.] 9. The loss of this character is associated with the loss of purposeful aliveness itself. (The premise of L'Avventura is the disappearance of Anna, who has been accompanied to an island by her lover, a middle-aged architect with whom she has been having an unhappy affair. We never get to know Anna well enough to understand the basis of her unhappiness, because she disappears so early in the film, but we soon discover that the man who is left behind is in a state of archetypal ennui, a moral collapse characterized by an aimlessly cruel sexual pursuit of one of Anna's friends and a spoiling envy of the creativity of a younger man who can still take pleasure in making a drawing of an Italian building.) [In L'Avventura especially, Beebe added, you can witness the process of a "puer" becoming a "senex" without having incorporated his anima, as a process of petrification. He offered as an alternate example the story of Vertigo, which he explores more thoroughly in the above-referenced article.]

9. The loss of this character is associated with the loss of purposeful aliveness itself. (The premise of L'Avventura is the disappearance of Anna, who has been accompanied to an island by her lover, a middle-aged architect with whom she has been having an unhappy affair. We never get to know Anna well enough to understand the basis of her unhappiness, because she disappears so early in the film, but we soon discover that the man who is left behind is in a state of archetypal ennui, a moral collapse characterized by an aimlessly cruel sexual pursuit of one of Anna's friends and a spoiling envy of the creativity of a younger man who can still take pleasure in making a drawing of an Italian building.) [In L'Avventura especially, Beebe added, you can witness the process of a "puer" becoming a "senex" without having incorporated his anima, as a process of petrification. He offered as an alternate example the story of Vertigo, which he explores more thoroughly in the above-referenced article.]