Suffering the dog days of Summer in Boise, Idaho, I regret all the more not being able to attend this year's Fantasia International Film Festival (Fantasia), where I usually escape in late July-early August. Admittedly, Montreal has its own potential to steam me out, but at least at Fantasia I can spend most of my time in air-conditioned movie theaters watching my first and favorite passion: genre films.

Still, not being able to attend in person this year has afforded an opportunity to explore an experience of Fantasia contingent upon the generosity of publicists willing to share streaming links, and access to (at least) archival films incorporated into the program on such online platforms as Vudu and Netflix. In other words, I still have access to content, if not community. There's an argument to be made—and film festival scholar Dina Iordanova has recently made it at EatDrinkFilms—that "nowadays (and especially in view of the growing practice to stream content across borders), the films that show at a festival can be seen in multiple contexts. It is no longer necessary to go to a specialist film festival to see the films. More and more one goes to a festival for the socializing and the togetherness. The cohesive power of an event is in its 'liveness', and no longer in its expertly programmed content." [Citations omitted.]

It is, in fact, Fantasia's "live" events and workshops that are especially rewarding, which I sincerely regret missing, along with sharing the spectatorial experience with an enthusiastic fan-based audience. Case in point would be their program "Dirty Movies: A History of the 'Stag' Film", scheduled for Sunday, August 3, 9:15PM in the J.A. De Seve Theatre. Sponsored by Le Cinéclub de Montréal: The Film Society (C/FS), this combination lecture and screening event will be hosted by Philippe Spurrell (C/FS) and Thomas Waugh (Concordia University Research Chair in Sexual Representation and Documentary, Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema).

Le Cinéclub de Montréal's Philippe Spurrell contextualizes the screening in his program capsule: "Beginning many decades ago, in an age when explicit erotic imagery was taboo, 16mm projectors were set up in secret darkened rooms, where risky stag films showed generations of people everything they wanted to know about sex. Even more risky than viewing them was actually filming them, but that didn't stop some directors from being creative, funny and outrageously daring. We will explore the origins and development of the genre from its early days through the 1970s.

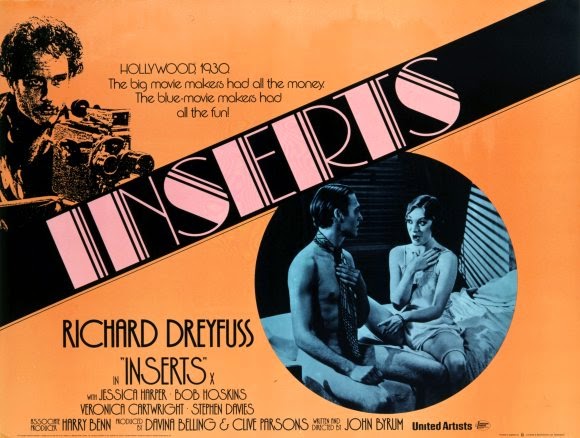

"The centerpiece of this exploration is the little-seen Inserts (1974). This black comedy, written and directed by John Byrum, tells the story of a washed-up silent-movie director who reboots his career by making films in his crumbling mansion for the growing XXX market. Playing the lead in this major studio release is Richard Dreyfuss (Jaws, CE3K), who took on this small project as a quiet break following months of insanity on a big-budget film he predicted would flop because it featured a giant mechanical rubber shark. Other key players who give intense (and quite revealing) performances are Veronica Cartwright (Alien) and Jessica Harper (Phantom of the Paradise, Suspiria). The late great Bob Hoskins (Brazil, Roger Rabbit) plays a money man named Big Mac. Very theatrical and oddly compelling, Inserts still has the ability to shock modern audiences, who get drawn into its cast of damaged characters and its intelligently acidic screenplay by a director who successfully pitched the idea to a producer riding in the New York taxi he was driving.

"PLUS: Preceding the feature will be unedited footage of iconic pin-up Betty Page struck directly from 16mm camera negatives, and original vintage 16mm prints of shorts actually played at stag parties many decades ago, including a short film shot at the notorious Manson Family lair Spahn Ranch—and a clip from If You See Kay. If you do see her, tell her not to miss all these rare moving images pulled from the Cinéclub/Film Society vaults, all to the benefit of your sexual education! (Strictly 18+)"

Though he had admitted reservations about Inserts and didn't consider it successful, Roger Ebert nonetheless conceded it was "an odd and ambitious little movie" with "a certain quirky charm." In other words, "it's interesting and it has its moments." At the Chicago Reader, Jonathan Rosenbaum opined: "Chances are you'll either be bored stiff by the conceits or exhilarated; personally, I found it gripping throughout."

Vincent Canby of The New York Times categorized Inserts as "essentially a stunt, a slapstick melodrama in the form of a one-act, one-set, five-character play. It is, however, a very clever, smart-mouthed stunt that, in its self-described 'degenerate' way, recalls more accurately aspects of old Hollywood than any number of other period films, including Gable and Lombard. It's not anything that Inserts says, but something to do with the dizzy pace, the wisecracks, the lack of sentimentality and, mostly, the characters, who could be shadowy parodies of once-living legends."

With his customary poetic prowess, Fernando Croce offers: "Between silents and talkies (art and exploitation? body and soul?), 'the valley of indecency.' The key is Richard Dreyfuss' resemblance to Josef von Sternberg as a ruined auteur scrambling for genital close-ups circa 1930, the rest of this Hollywood-Babylon apparition falls in place as brackish facsimiles of Jeanne Eagels, Louis B. Meyer, et al. ...Cinema is alternately equated to bootlegging, grave-digging and meat-wrapping and unwrapping, yet Fassbinder's holy whore in John Byrum's sardonic exposition of the artist's dilemma is also a vivacious gal in a cyclone of splayed crotches and wisecracks. ...[R]eviewers got stuck on the X-rating and, like the trenchcoaters in the opening scene, fumbled in the dark wondering 'where the fuck's the cum shot?' "

I'm glad Croce mentions that opening sequence because it sets up the cultural context of the stag parties where porno films—like the one being made in the movie—were exhibited. Here, I will lean heavily on the scholastic work of Thomas Waugh, who I have long admired, met in San Francisco in June 2001 (before I began writing on film), and wish I could have interviewed in Montreal (now that I do write on film). I will especially rely on his commentary on stag films from his volume Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from their Beginnings to Stonewall (in which he inscribed: "Dear Michael, Happy Reading!"), and his essay "Homosociality in the Classical American Stag Film: Off-Screen, On-Screen" published in Porn Studies, edited by Linda Williams (Duke University Press, 2004).

According to Waugh, stag parties (or "smokers", as they were sometimes called in the U.S.) were a form of non-theatrical distribution for stag films where "itinerant projectionists would provide an evening of reels on command. Younger audiences belonged to college fraternities, while members of benevolent societies such as the Shriners made up the already-initiated part of the constituency." Apparently, the law tolerated this semiclandestine circulation and in Bloomington, Indiana, the American Legion even went so far as to announce their smokers in the local paper.

"In both European and American contexts," Waugh writes, "the screenings had both an instructional and a communal function, operating as instruments of socialization and initiation. How did audiences respond? Not with the deadly silence that would later reign in the porn houses of the 1970s, but with a boisterous, interactive free-for-all. The films were silent of course, but both the intertitles and the audience repartee articulated an oral culture of masculine sexuality, drawing on both the folk tradition of vulgar humor and the personal bravado of individual spectators competing with each other."

Inserts—whose title is fraught with salacious double-entendres of penetration and intravenous drug use—likewise inserts its audience among the rowdy crew of the film's opening sequence who immediately begin heckling the first few fluttering frames of the projected reel. Straightaway are complaints that the film is in black-and-white, not color (throughout the film director Byrum shifts between color and black-and-white to distinguish between art as complicated and ongoing process and art as the finished—and surprisingly innocent—artifact). Harlene (a startlingly disrobed Veronica Cartwright) and Rex, the Wonder Dog (Stephen Davies) simulate an over-the-top ascot-strangulation and rape scene.

My first thought when seeing Stephen Davies enter the frame naked with only an ascot around his neck was that he wasn't bad-looking and had a good build, which was uncharacteristic of most of the men in these early stag films whose out-of-shape bodies were rarely shown (the focus being—allegedly—on women's bodies), and were often masked to assert their anonymity and render the women even more abject. Davies enters the frame and someone in the audience shouts out, "Looks like a homo to me" and is met with, "It takes one to know one." The film will reveal that Rex, the Wonder Dog is, indeed, homosexual and that the reel's director "Boy Wonder" (Dreyfuss) suffers from impotence both sexual and creative, unable to get his "rope to rise." When the final complaint shouted out at this stag reel is, "Where the fuck's the cum shot?", Inserts' opening credits roll and we're taken to the scene of the cinematic crime to discover why, in fact, there is no fucking cum shot.

This brief, boisterous opening scene can be unpacked in several ways. First, as already mentioned, as a culturally-specific mode of specularization that—as Waugh has argued—serves both an initiatory and socializing function. The "narrative" of Boy Wonder's reel is simple and straightforward. Harlene (Cartwright) mocks Rex's dick and is punished for it by being strangled with his ascot and then savagely raped. As one of the few female members at this smoker complains in disgust, "You guys are sick!"

Waugh identifies that sickness as the "great American pop culture tradition of genital aphasia of the postwar era, shaped by censorship, yes, but also by shame and disavowal", implying that the inability to talk about sex, and genitalia in particular, was a mental disorder peculiar to the culture at the time. Aphasia, a medical complication that robs a victim of the ability to understand written and spoken language, though medically a physical malady, is here metaphorically applied as a cultural and psychological affect; i.e., a "consistent pattern of denial."

Waugh pulls no punches in asserting that stag films are a "paradoxical, primitive, and innocent art form that seeks cunt and ... discovers prick." Clearly, they were films "presumably directed by men, and ultimately sutured within the framework of male subjectivity." He asks what these films and the stag parties thrown to show them teach us directly, even indirectly, about men? He suggests: "The whole mosaic of underground erotic film and its spin-off genres does more than expose men's gazes and gestures, and even the occasional full-shot male body. It also expresses the spectrum of male sociality, the experience of having a penis (and being white) in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. For in front of and behind the camera, on the screen and in the screening room, this spectrum radiates in all its ambiguities and over-determinedness, however hermetic, abstract, individualized, and displaced the narratives are." If stag films did indeed seek cunt and discover prick, they also discovered that pricks live in packs, which is precisely their initiatory and socializing function.

Let's pursue that "spectrum of male sociality" by exploring what Waugh argues is "the homosocial core of masculinity as constructed within American society" tenaciously engaged by stag films, both on-screen and off-screen. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick earlier identified this "homosocial continuum" and defined "homosocial desire" as "the affective or social force, the glue, even when its manifestation is hostility or hatred or something less emotively charged, that shapes an important relationship [between men]."

Waugh likewise cites John. H. Gagnon and William Simon as the only social scientists studying the stags' subcultural milieu. Even earlier than Sedgwick, they wrote in 1967 that the primary referent of stag films lay "in the area of homosocial reinforcement of masculinity and hence only indirectly a reinforcement of heterosexual committments."

Now we are getting, as they say, to the meat of the matter.

"Above all," Waugh continues, "the specularization of homosocial desire is in place, in the screening room and on the screen: men getting hard pretending not to watch men getting hard watching images of men getting hard watching or fucking women." (I absolutely love that quote.) Waugh wonders why Dr. Kinsey—who was intensely aware of stag movies as an element in the erotic socialization of American (white) men and asked his respondents about the use of the stag film as an object of arousal—curiously failed to ask them "about the context of erotic stimulation, about the same-sex collective public sharing of these cine-homoerotic stimuli."

Waugh asks: "What about homosociality on-screen? The screen, like a mirror, reflected many of the same dynamics unfolding in the screening room." He cites several examples of films where "men share women, men get off watching men with women, men help men with women, men supplant men with women, men procure women for men, and so on."

Let's turn now to Veronica Cartwright's performance as Harlene—whose name is an inch away from harlot. This is, without question, one of Cartwright's finest performances, steering away from the stereotyped weeping and sniffling seen in her childhood performances (The Children's Hour, The Birds) up through their adult inflections (Alien, Invasion of the Body Snatchers). From the moment she opens her mouth, it becomes apparent why she is a fallen silent screen star reduced to making blue movies. Like Jean Hagen's character in Singin' in the Rain (1952), talkies destroyed her career as a silent screen star because her squeaky voice couldn't meet up to the demands of the medium; but, whereas Hagen's Lina Lamont was a comic villain—the diva audiences loved to hate—Cartwright's Harlene is a truly likeable, if horribly damaged, soul whose former career has spiraled downward into drug use and debauchery. If she is a harlot, she is the proverbial harlot with a heart of gold.

Just as Inserts' heckling audience in the first scene tagged the actor in the stag film as a homo, the presumption would have been that the actress was a whore. "The hooker presides over the entire corpus of stags in a generalized way," Waugh writes, "inflected by the familiar hypocritical class-centric contempt for the working girl since the audience undoubtedly assumed the female performers to be sex workers—and most clearly they often were as much, just as their inept male partners were assumed to be, and visibly were, amateurs. (In fact, pursuing this documentary reading, the stag corpus may well be the best visual ethnography of sex workers in America during this period.) Many of the performers were decades older and less trim than the prevailing ideal of the sixteen-year-old Candy Barr, adding the complication of age to the misogynist economy at play around the sex worker.

"On a literal level, the hooker is incarnated specifically in character types who exchange sex for money, not desire. ...Few literally drawn prostitute characters appear in the stag stories as such, but the recurring exchange of money and services implies that most female characters are candidates. This element of populist male blame which channels the stresses of masculinity awakened by the stag-film setting, this social scapegoating attached to the attractive / repulsive lumpen femme fatale, of course makes for a familiar element in popular and high art of the period." Contempt, Waugh argues, centers on the seller and not the buyer.

By contradistinction, Jessica Harper's Cathy Cake arrives on-set with her mobster pal Big Mac (Hoskins) only "to watch" the proceedings; but, her prurient interest is a thin guise over her ambitious self-interest and rampant desire. She represents the "other" taboo: the woman who initiates; the woman who wants it. And yet by her very agency she sets into motion the reason why Boy Wonder's stag film doesn't have a cum shot and—at the same time in a parting glance between them—confirms that for the two of them making a stag film together offered a momentary sense of creating meaningful art.

At the very least, she gets Boy Wonder's rope to rise (though at first she feigns naïvete: "What does that mean 'rope to rise'? Do you have a magic act?"). And oddly enough—and reason enough for an "X" rating, I guess—his erection redeems an impotent creativity and, more broadly, an abandoned community of artists who still struggle to create something, even if it is nowhere near the peak of their previous careers, lapsing from the licit into the illicit. Just as the initiatory and socializing aspects of misogyny utilize pornography to serve a masculinist culture, impotence is likewise an important informing factor. In his seminal lecture on pornography ("Pink Madness: Why Does Aphrodite Drive Us Crazy With Pornography?"), Jungian theorist James Hillman suggested impotence as the ground for the erotic imagination and its compensatory fantasies. You see Boy Wonder come "alive" while shooting the strangulation-rape scene in a kind of frenzied joy that is offset by his gentler, more genuine joy when he comes "alive" making love to Miss—"please call me Cathy"—Cake. Their final exchanged glance is bittersweet with their shared hunger for a genuine life and the momentary satisfaction that perhaps only artifice can provide.

Finally, let's get back to that homo actor and his role in all of this. By, once again, inserting homosexuality into an allegedly heterosexual enterprise, suggestion is made of the homosocial continuum vital to American culture at the time, and the important role homosexuals played in helping heterosexual men hold onto their vulnerable self-definition. I can't help but quote Fran Lebowitz, who quipped: "If you removed all of the homosexuals and homosexual influence from what is generally regarded as American culture, you would pretty much be left with Let's Make a Deal."

Waugh goes on in his research to explore the shift from stag films to gay physique films—which, naturally, exceeds the scope of this review—but suffice it to say that he argues that "like the stags, the physique films were made by men for men about men, and thus they, too, center around the specularization of masculinity, and fall along the spectrum of homosociality." They overlap "mostly in the homosocial codes and formulas: rivalry and sharing, display and specularization, trickery and triangles, crescendo and release. And the logic of surrogacy, fetish, and tongue-in-cheek coding—from frenzied wrestling as a knowing simulacrum of fucking to fun with spears and guns and boots." I could readily cite the arousing scene between Rupert (Alan Bates) and Gerald (Oliver Reed) in Ken Russell's Women In Love (1969) as an example of the first surrogacy, and all the Men's adventure magazines of the fifties and sixties (and their illustrated pulp covers) as an example of the second, or even the now well-documented gun rivalry between Montgomery Clift and John Ireland in Howard Hawks' Red River (1948).

Waugh concludes: "Comparing, then, the stag corpus and its physique underbelly, one is overwhelmed by how much social status and audience infrastructure differently determine the iconographies of desire. But, in fact, the two genres were moving in similar directions at the beginning of the sexual revolution in the fifties, both of them poised nervously on the same homosocial continuum of desire. Both were also eagerly embracing new technologies, 16mm, 8mm, soon super-8, and eventually that electronic panacea that was still a gleam in the producers' eyes in 1968, home video. Thanks to these technologies, both traditions penetrated the domestic sphere, the physique films through aboveground mail order, the stag films through under-the-counter sales (the days of the itinerant projectionists had passed). Both stags and physiques in mutated form would also erupt into the hard-core features of tenderloin theatrical circuits in the late sixties and early seventies—the entrenchment of homosocial male eroticism in the marketplace of the commodified sexual revolution. These two interrelated corpuses, these mosaics of homosociality, ... thus reentered the public patriarchal sphere together, arm in arm, pricks in hand."

SOURCES CITED

Gagnon, John H., and William Simon. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality. Chicago: Aldine, 1973: 266.

Hillman, James. "Pink Madness: Why Does Aphrodite Drive Us Crazy With Pornography?" Spring audio, 1995.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985:2.

Waugh, Thomas. Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from their Beginnings to Stonewall. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996: 309-311.

Waugh, Thomas. "Homosociality in the Classical American Stag Film: Off-Screen, On-Screen." In Porn Studies, ed. Linda Williams. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004: 127-141.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Thursday, July 24, 2014

FANTASIA 2014—Cybernatural (2014)

Earlier this year, I reviewed Walter Woodman and Patrick Cederberg's Noah (2013), a 17-minute short that screened at the Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival in that festival's hybrid documentary sidebar. Essentially depicting the potential for miscommunication rife on such a disembodied medium as the internet, Noah ingeniously crafted itself out of the now-commonplace practice of multitask browsing between online platforms, assembling screenshots of Google search functions, Facebook messaging, SKYPE sessions, Gmail, YouTube, Wikipedia, Chat Roulette, gaming, iTunes, and iPhone texting, narratively framed on a Macbook desktop. "If you can accept that the cinematography of the film is simply watching someone browse Facebook," Ollie England astutely noted at Crispy Sharp Film, "then the narrative and the message of the film is pure zeitgeist."

What fascinated me with Noah was how much personality and emotion was conveyed by the mere hesitancy or indecision of a cursor arrow, and the captivating tension of real-time pauses and ellipses in keyboard activity. Noah's brief narrative swiftly builds traction with all the momentum of an overheated mouse caught in its own trap.

I mention Noah to acknowledge its precedence. It's a brilliant little hybrid documentary that's all but assured of being bowled over and forgotten by the most recent iteration of its filmic conceit: Leo Gabriadze's Cybernatural (2014) [IMDb / Facebook], which recently saw its world premiere at the Fantasia International Film Festival, becoming Fantasia's first runaway sleeper hit, and earning it an encore screening (next Tuesday, July 29, 9:45PM, De Seve Theatre). Granted, Gabriadze and his writer Nelson Greaves have amplified that conceit by applying it to the horror genre, succeeding in structurally becoming something very much like Noah, but admirably distinct in the application of that structure, intent (and successful) in generating a much more menacing atmosphere satisfying the expectations of the genre and its disturbingly relevant theme of cyberbullying.

As Fantasia programmer Mitch Davis pitched in his program capsule: "Through the stacking of plot twists, character riffs and the many open interfaces, private messages and video chat windows, it pulls off the dual miracle of making its world real while never feeling static, its storytelling innovative, engrossing and horrifically relatable. In fact, Cybernatural nails the processes of how people communicate online in a way we've never seen done before. The familiar tones of incoming Skype calls and iMessages, the ingrained-into-every-atom-of-our-beings interfaces of Facebook and Twitter, the background use of iTunes, all of it, are put to ingenious use, serving as portals into character's deeper selves."

A year after Laura Barnes committed suicide at her high school following the posting of a humiliating video online that went viral, her "cybernatural" spirit invades a group chat session between six of her schoolmates who she suspects of posting the video whose toxic shaming drove her to suicide. At first, the six believe her presence to be a prank until dark secrets begin to be revealed that confirm her identity and her determination to exact revenge. It's a cat and mouse (pun intended) game.

"In an age boiling over with lethal cyberbullying and slut-shaming," Davis continues, "where kids commit suicide in front of their webcams and exes take revenge on one another by posting compromising pics snapped in earlier moments of trust, could there possibly be a more timely or pertinent genre film than Cybernatural?"

With Timur Bekmambetov (Nightwatch, Wanted) taking on producer credits, Gabriadze and Greaves guide their youthful cast—which includes Shelley Hennig (Teen Wolf), Jacob Wysocki (Terri) and hottie William Peltz (In Time)—through character-etched paranoia and escalating tension. Along with the aforementioned suspense generated from hesitant personality-driven cursor activity, Cybernatural also employs juddering distressed video and distorted sound to ensure discomfort and fear. (It's of interest to note that the distressed irresolute image has become a popular trope of the horror genre, used to maximum effect in such films as VHS and Resolution.) The repeated insertion of a Wikipedia page on demonic possession felt a bit like being hit over the head, but such minor stumbles were wholly redeemed by near brilliant comic antistrophes—our cybernatural antagonist remotely plays Connie Conway singing "How You Lie, Lie, Lie" on Spotify to offset the escalating revelations of playing the "Never Have I Ever" game and the spectacular Facebook animation of Jess (Renee Olstead) being bludgeoned to death and dismembered to the tune of "You Can't Stop Me." Our ghost in the machine has a wicked sense of humor.

In its marketing campaign Cybernatural claims the film redefines "found footage" for a new generation of teens; but, I find that claim inexact and misleading. What Noah and Cybernatural are achieving is not something found as much as constructed; "stacked" as Mitch Davis phrased it. I'm not quite sure what the exact term would be for this new style of footage—in innovation it does resemble what Blair Witch did with found footage—but it's dissimilar in key ways for staging a new form of audience identification more in league with cinematic découpage than found footage. For lack of a better term, let's call it cyberdécoupage—with its attendant aesthetics of stacked media assemblage—which is how I will monitor the technique in films to come. I anticipate a cascade of genre knock-offs.

At Fangoria, Michael Gingold concurs that "lumping Cybernatural in with the usual run of found-footage movies—even to call it a standout example—isn't quite fair, as it takes the form into different, relevant directions."

Another insight Gingold offers on the film is its succinct summation of the way sexual and violent expressions have become normalized and conflated on-line. Gingold adds: "With cyberbullying such an unfortunately common occurrence these days, Gabriadze and Greaves are working with provocative and touchy subject matter here. They rise to the occasion by treating it as serious business with long-ranging consequences [the film's tagline: "On the internet your sins live forever"], resisting the urge other filmmakers might have felt to tart it up—and trivialize it—with a lot of schlocky horror tropes. Nor are there completely clearcut heroes and villains here, as it's revealed over the course of the movie that Laura was something of a bully herself. While channeling the anger and frustration many feel over this syndrome, Cybernatural also uses it as fuel for one truly frightening ride. It works great with an audience, where the aforementioned familiarity enhances the shared viewing experience, but it will likely be just as effective—or perhaps even more so—when viewed on one’s own personal device."

I can vouch for that last observation. Unable to attend Fantasia in person this year, Cybernatural's publicists were generous enough to provide a streaming link, which watched late at night on my home computer had me jumping in my desk chair as at times it was indeterminate if the sounds and images I was experiencing were in the film or on my desktop.

At Bloody Disgusting, Síofra McAllister argues that Cybernatural scratches the "technophobic itch" with a deceptively simple format that "taps into a universal theme that has, until now, remained elusive in genre movies despite its prevalence in our 21st century psyche: the fear that technology has given us the tools to destroy each other—and ourselves." McAllister writes: "The demonic possession trope is a tricky one to get right at the best of times, but playing on our dystopian dread of the digital footprint we're all leaving behind, Cybernatural combines the paranormal and science fiction genres with all the familiar fixings of our online lives to create a monster that's as relatable as it is terrifying. Who's watching your Skype calls? Who can trace that misguided video you posted? And just how much of ourselves do we internet users unwittingly expose—and leave behind?" Sins, indeed.

At Dread Central, Matt Boiselle wryly disclaims: "If you have no patience for the myriad of technological advances that we've endured in our lifetime, then Cybernatural is NOT the film for you. However, if you're a Twittering, Skyping, Facebookin' kind of Googler that loves to SnapChat selfies to your Instagram, then this movie is right up your USB port."

What fascinated me with Noah was how much personality and emotion was conveyed by the mere hesitancy or indecision of a cursor arrow, and the captivating tension of real-time pauses and ellipses in keyboard activity. Noah's brief narrative swiftly builds traction with all the momentum of an overheated mouse caught in its own trap.

I mention Noah to acknowledge its precedence. It's a brilliant little hybrid documentary that's all but assured of being bowled over and forgotten by the most recent iteration of its filmic conceit: Leo Gabriadze's Cybernatural (2014) [IMDb / Facebook], which recently saw its world premiere at the Fantasia International Film Festival, becoming Fantasia's first runaway sleeper hit, and earning it an encore screening (next Tuesday, July 29, 9:45PM, De Seve Theatre). Granted, Gabriadze and his writer Nelson Greaves have amplified that conceit by applying it to the horror genre, succeeding in structurally becoming something very much like Noah, but admirably distinct in the application of that structure, intent (and successful) in generating a much more menacing atmosphere satisfying the expectations of the genre and its disturbingly relevant theme of cyberbullying.

As Fantasia programmer Mitch Davis pitched in his program capsule: "Through the stacking of plot twists, character riffs and the many open interfaces, private messages and video chat windows, it pulls off the dual miracle of making its world real while never feeling static, its storytelling innovative, engrossing and horrifically relatable. In fact, Cybernatural nails the processes of how people communicate online in a way we've never seen done before. The familiar tones of incoming Skype calls and iMessages, the ingrained-into-every-atom-of-our-beings interfaces of Facebook and Twitter, the background use of iTunes, all of it, are put to ingenious use, serving as portals into character's deeper selves."

A year after Laura Barnes committed suicide at her high school following the posting of a humiliating video online that went viral, her "cybernatural" spirit invades a group chat session between six of her schoolmates who she suspects of posting the video whose toxic shaming drove her to suicide. At first, the six believe her presence to be a prank until dark secrets begin to be revealed that confirm her identity and her determination to exact revenge. It's a cat and mouse (pun intended) game.

"In an age boiling over with lethal cyberbullying and slut-shaming," Davis continues, "where kids commit suicide in front of their webcams and exes take revenge on one another by posting compromising pics snapped in earlier moments of trust, could there possibly be a more timely or pertinent genre film than Cybernatural?"

With Timur Bekmambetov (Nightwatch, Wanted) taking on producer credits, Gabriadze and Greaves guide their youthful cast—which includes Shelley Hennig (Teen Wolf), Jacob Wysocki (Terri) and hottie William Peltz (In Time)—through character-etched paranoia and escalating tension. Along with the aforementioned suspense generated from hesitant personality-driven cursor activity, Cybernatural also employs juddering distressed video and distorted sound to ensure discomfort and fear. (It's of interest to note that the distressed irresolute image has become a popular trope of the horror genre, used to maximum effect in such films as VHS and Resolution.) The repeated insertion of a Wikipedia page on demonic possession felt a bit like being hit over the head, but such minor stumbles were wholly redeemed by near brilliant comic antistrophes—our cybernatural antagonist remotely plays Connie Conway singing "How You Lie, Lie, Lie" on Spotify to offset the escalating revelations of playing the "Never Have I Ever" game and the spectacular Facebook animation of Jess (Renee Olstead) being bludgeoned to death and dismembered to the tune of "You Can't Stop Me." Our ghost in the machine has a wicked sense of humor.

In its marketing campaign Cybernatural claims the film redefines "found footage" for a new generation of teens; but, I find that claim inexact and misleading. What Noah and Cybernatural are achieving is not something found as much as constructed; "stacked" as Mitch Davis phrased it. I'm not quite sure what the exact term would be for this new style of footage—in innovation it does resemble what Blair Witch did with found footage—but it's dissimilar in key ways for staging a new form of audience identification more in league with cinematic découpage than found footage. For lack of a better term, let's call it cyberdécoupage—with its attendant aesthetics of stacked media assemblage—which is how I will monitor the technique in films to come. I anticipate a cascade of genre knock-offs.

At Fangoria, Michael Gingold concurs that "lumping Cybernatural in with the usual run of found-footage movies—even to call it a standout example—isn't quite fair, as it takes the form into different, relevant directions."

Another insight Gingold offers on the film is its succinct summation of the way sexual and violent expressions have become normalized and conflated on-line. Gingold adds: "With cyberbullying such an unfortunately common occurrence these days, Gabriadze and Greaves are working with provocative and touchy subject matter here. They rise to the occasion by treating it as serious business with long-ranging consequences [the film's tagline: "On the internet your sins live forever"], resisting the urge other filmmakers might have felt to tart it up—and trivialize it—with a lot of schlocky horror tropes. Nor are there completely clearcut heroes and villains here, as it's revealed over the course of the movie that Laura was something of a bully herself. While channeling the anger and frustration many feel over this syndrome, Cybernatural also uses it as fuel for one truly frightening ride. It works great with an audience, where the aforementioned familiarity enhances the shared viewing experience, but it will likely be just as effective—or perhaps even more so—when viewed on one’s own personal device."

I can vouch for that last observation. Unable to attend Fantasia in person this year, Cybernatural's publicists were generous enough to provide a streaming link, which watched late at night on my home computer had me jumping in my desk chair as at times it was indeterminate if the sounds and images I was experiencing were in the film or on my desktop.

At Bloody Disgusting, Síofra McAllister argues that Cybernatural scratches the "technophobic itch" with a deceptively simple format that "taps into a universal theme that has, until now, remained elusive in genre movies despite its prevalence in our 21st century psyche: the fear that technology has given us the tools to destroy each other—and ourselves." McAllister writes: "The demonic possession trope is a tricky one to get right at the best of times, but playing on our dystopian dread of the digital footprint we're all leaving behind, Cybernatural combines the paranormal and science fiction genres with all the familiar fixings of our online lives to create a monster that's as relatable as it is terrifying. Who's watching your Skype calls? Who can trace that misguided video you posted? And just how much of ourselves do we internet users unwittingly expose—and leave behind?" Sins, indeed.

At Dread Central, Matt Boiselle wryly disclaims: "If you have no patience for the myriad of technological advances that we've endured in our lifetime, then Cybernatural is NOT the film for you. However, if you're a Twittering, Skyping, Facebookin' kind of Googler that loves to SnapChat selfies to your Instagram, then this movie is right up your USB port."

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

YBCA: BAN7—INVASION OF THE CINEMANIACS!

Bay Area Now (BAN), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts' (YBCA) signature triennial, has for six years running brought to life current perspectives for both YBCA and the regional art scene through the work of artists who capture the spirit of "now." In its seventh edition, BAN7 is experimenting with a new curatorial approach that highlights collaborations with the region's artists and arts organizations and pushes beyond presentation—what Dina Iordanova terms "descending programming"—toward a multidisciplinary celebration of the diversity of artistic practices in the Bay Area.

BAN7's core idea is to decentralize the curatorial process, and centralize the public presentation of some of the most exciting artistic voices in the region today. As a common shared site for the presentation of works, BAN7 aims to create a lucid web of creative activity in the Bay Area. Their vision is to create a platform for new work and experimentation rooted in the belief that a decentralized curatorial process will open up an opportunity for a wider range of voices and create spaces for dialogue beyond the arts.

In conjunction with BAN7's core curatorial initiative, Joel Shepard, YBCA's Film / Video Curator assembled this Summer's film program "Invasion of the Cinemaniacs" to inflect that initiative. As he states it in his curatorial statement: "When I took this job at YBCA over 15 years ago, I decided immediately that I would not be the only curatorial voice that got to be heard in our Screening Room. I knew very well what a smart and engaged film community we had here, and knew it would be a big mistake to try to speak for all those individuals and communities. My solution then was to make partnerships with a great number of local media organizations, who would host weekly or monthly screenings here. These included groups such as the SF Jewish Film Festival, Film Arts Foundation, Cine Acción, Frameline, Goethe-Institut, San Francisco Cinematheque, and many more. Some of these groups are now long gone, some are alive and well. And some still do regular screenings here.

" 'Invasion of the Cinemanaics!' presented as part of BAN7, is really an extension of this original impulse, but takes it to a deeper, different level. There is a community in San Francisco of avid cinephiles. You might not know their names, but you've seen them around. Some of them write excellent blogs about the local film scene. I wanted to celebrate these folks, who are so strongly invested in local film exhibition, but generally don't get to have a say in what actually gets screened. I realized I could take this idea a little further, and reach out into the world of film criticism, publicity, and other areas where people were building communities around screenings, like Meetup groups.

"I asked everyone to choose a film of special significance to them, without any restrictions. We only had enough slots for ten people (plus one super-sized sidebar event presented by Jesse Hawthorne Ficks), but we could have had a lot more. Many great, dedicated people got left out—for now. But, this was such fun to put together we will definitely do it again, so stay tuned. And the film program, taken as a whole, is amazing. We've got an incredible diversity of some very rare, stunning films. Where else would you find classic Korean cinema next to Mexican psychodrama, alongside Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Bronson, and camp icon Maria Montez? Join us for this unique experiment in film curating."

Imagine my delight in being invited to be among the first wave of "cinemaniacs" to offer a film to this significant, brave program. As a former anthropologist, urban models of the core and periphery have long captured my imagination and my intellect and—in many ways—my current lifestyle of frequently shifting between the San Francisco Bay Area and my (now relatively) new home in Boise, Idaho has been living practice of how cultural flows operate and traffic. By what I have offered the Bay Area over the last decade through entries on The Evening Class, I understand that I will always be recognized as a San Franciscan, even if I reside somewhere else, and Joel Shepard's invitation to join the Cinemaniacs series was respectful confirmation of that. My only regret is that I'm unable to catch all of the series in person, though I will fortunately be able to catch several.

"Invasion of the Cinemaniacs" kicked off this past Sunday with publicist Karen Larsen's choice of The Hole (1998), a "gonzo gem" from Taiwan by Tsai Ming-liang, screened in 35mm. Somewhere in Taiwan, the rain won't stop. A mysterious disease reaches epidemic proportions. A young man uses the giant hole in his living room floor to spy on his downstairs neighbor, a woman who stockpiles toilet paper and dreams of singing and dancing… The Hole is Tsai Ming-liang's craziest and most entertaining film, a tragicomic tale of urban loneliness.

In the early '70s, Karen Larsen founded Larsen Associates, a public relations firm specializing in independent feature and documentary films, film festivals, and special events.

Tomorrow evening, Thursday, July 24, filmbud Brian Darr selects The Company (2003), an underrated film from the end of Robert Altman's oeuvre. Robert Altman's penultimate theatrical film allowed him to apply his classic approach of "community as character" to an existing organism: Chicago's Joffrey Ballet. By integrating actors Malcolm McDowell (as fictional Artistic Director Alberto Antonelli), Neve Campbell (as a striving dancer), and James Franco (as her romantic interest) into a cast of real professional dancers and choreographers, Altman gracefully pirouettes between subtle observational drama and the magnetic forces of star charisma. In chronicling a typical season of a 21st century arts institution, his camera rarely captured such spectacular motion and color. The result is arguably his most underrated and Wiseman-esque masterwork.

Brian Darr was born and raised in San Francisco and currently works in the San Francisco Public Library's audiovisual department. In 2005 he founded the blog Hell On Frisco Bay, and has been highlighting local film screenings there (and more recently on Twitter as @HellOnFriscoBay) ever since. He's also written essays for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Senses of Cinema, Fandor, and the 2013 book World Film Locations: San Francisco.

Here is the remaining schedule:

Jonathan L. Knapp presents Colorado Territory (1949, 94 min, 35mm) by Raoul Walsh on Sunday, July 27, 2:00PM. A remake of his film High Sierra (1941), Walsh's noir western inhabits a space not far removed from that of his broody Pursued (1947). As in High Sierra, here we have the tale of an aging criminal (Joel McCrea) convinced to pull one last heist. But of course things go awry: there's double crossing, a love triangle (Dorothy Malone and especially Virginia Mayo do great work here), and the general sense that the past is an inescapable force that must be reckoned with. Ghosts haunt the landscape of Colorado Territory, proving that the shadows of postwar Hollywood stretched far beyond the dark city.

Jonathan L. Knapp has spent nearly a decade in the local film community, whether through writing for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, or working for film festivals such as the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival and Frameline. After several years at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Knapp came to YBCA, where he has worked for the past three years as Film / Video Curatorial Assistant. Simultaneously, he completed an MA in cinema studies at San Francisco State University, and is leaving his position at YBCA this summer to pursue doctoral work in film and visual studies.

Cheryl Eddy presents Death Wish 3 (1985, 92 min, 35mm) by Michael Winner on Saturday, August 9, 7:30 PM. His wife is murdered in Death Wish (1974). His daughter gets it in Death Wish II (1982). So in 1985's Death Wish 3, architect-turned-vigilante Paul Kersey (stone-cold Charles Bronson) has ascended to his true form: lone wolf with a heart of gold—and a white-hot temper. (You just can't keep a justice-loving man with access to a jaw-dropping array of firepower down, especially when New York City is crawling with so many violent scumbags.) Bleak and relentlessly brutal, Death Wish 3 is classic exploitation cinema with a distinctly 1980s flair; its villains are a street gang that manages to be both sinister and cartoonish ("They killed the Giggler!"), and its synth-heavy score is by none other than Jimmy Page.

Cheryl Eddy is the Senior Arts and Entertainment Editor at the San Francisco Bay Guardian, where she has worked since 1999. She holds an MA in cinema studies from San Francisco State University and is a member of the San Francisco Film Critics Circle.

Adam Hartzell presents Madame Freedom (1956, 125 min, 35mm) by Han Hyeong-mo on Sunday, August 10, 2:00PM. As Steven Chung, the Korean Studies scholar based at Princeton, notes, "the women's melodrama of the late 1950s was arguably one of the most important and influential of the period's mass cultural products." Melodrama is still a huge part of South Korean film, so much so that it seeps into other genres such as horror or war films. And the key melodrama of the 1950s was Han Hyung-mo's Madame Freedom, about a woman who flirts with a rapidly modernizing and westernizing South Korea. Come check out the fancy cafes, mambo dance halls, and French fashions of Gangnam Style, pre-Psy, in this classic film.

Adam Hartzell has been writing for the premier English-language website on South Korean cinema, Koreanfilm.org, since 2000. He has been published in The Cinema of Japan and Korea (Wallflower Press) and Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (Intellect Books). He has written often about the films of Hong Sangsoo, and recently presented a paper on his work at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Michael Guillén presents Hell Without Limits (El Lugar Sin Límites, 1978, 110 min, 35mm) by Arturo Ripstein on Saturday, August 23, 7:30PM. Less than five years after the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1973, Mexican filmmaker Arturo Ripstein bravely challenged entrenched social presumptions by inspiring compassion for the figure of La Manuela (Roberto Cobo), a not-very-attractive, elderly, cross-dressing whorehouse flamenco dancer at odds with the town's patriarch and his hired henchman Pancho (Gonzalo Vega), both of whom are intent on seizing Manuelita's properties. Complicating matters, La Manuela desires Pancho despite himself and seduces Pancho's own conflicted reciprocity. In a dazzling gender provocation, Ripstein maneuvers the narrative's power struggles to a choreographed denouement between the most feminized and the most machismo of men. Arturo Ripstein will be in attendance.

David Wong presents The Exile (1947, 95 min, 35mm) by Max Ophuls on Sunday, August 24, 2:00PM. The Exile overlays a familiar fable—that of the incognito prince in love with a commoner—onto the historical exile of England's Charles II to Holland in the 1650s. Director Max Ophuls got on well with producer-star-co-writer Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and was given free rein stylistically. Ophuls's trademark camera fluidity and compositional intricacy—used to devastatingly heartrending effect when tracing the psychological confinement of his female protagonists—achieve a more muted poignancy when utilized to underscore his outsider male protagonists' longing for the simple rituals of ordinary human connectedness.

David Wong writes: "I first began to take film seriously during a 1979 Francois Truffaut retrospective at the UC Theatre, Berkeley and have been attending local screenings with near full-time intensity since about 1980. I remain indebted to Professor Kaja Silverman, whose film theory classes at Cal in the early 1990s helped fill in the gaps created by mere film-viewing alone, and also to Max Ophuls, whose detached yet acutely-sensitive renderings of profound human emotion serve as a constant reminder of what is most valuable about cinema."

Alby Lim presents Pietà (2012, 104 min, digital) by Kim Ki-duk on Thursday, September 18, 7:30PM. Nobody likes Korean filmmaker Kim Ki-duk—you can only either hate him or love him. His movies aren't just dark; they're ugly, bleak, cheaply made, and just plain hard to watch. But they also explore human nature like few other movies do, and they win prizes for it. Take Pietà, Golden Lion winner for best film at the Venice Film Festival, about a ruthless debt collector whose life falls into turmoil when he meets a woman who may be his long-lost mother. It's savage, even a little preposterous, but it'll make you think long after its closing credits roll.

As organizer of The Red Lantern: Bay Area Asian Cinephiles, the world's largest Meetup for Asian films, Alby Lim hosts Asian film events in San Francisco and beyond.

Lynn Cursaro presents Little Fugitive (1970, 8 min, 16mm) by Morris Engel, Ruth Orkin, and Ray Ashley on Sunday, September 21, 2:00PM. Seven-year old Joey, tricked into thinking he has shot his brother, runs off to Coney Island, convinced he can never return home, and a gentle, bittersweet adventure begins. Co-directors Ruth Orkin and Morris Engel had impressive careers in photojournalism before they ventured into film. The immediacy and beauty of this tale of yearning have all the elements of the best street photography of the golden era of Life and Look magazines. As spunky and independent as its young hero, the film had a profound effect on François Truffaut's The 400 Blows, and D.A. Pennebaker said, "It spurred us all on." Preceded by the short Sun by Stelios Roccos.

Local film-goer Lynn Cursaro also curates 16mm treasures at SF's Oddball Archive, where she's on the lookout for wacky educational films and '30s curios. A staunch believer in film, she does not own a DVD player nor does she "stream."

David Robson presents The Brides Of Dracula (1960, 85 min, 35mm) by Terence Fisher on Thursday, September 25, 7:30PM. On her way to a new job in Transylvania, comely schoolteacher Marianne accepts the hospitality of the mysterious Baroness Meinster. The innocent Marianne accidentally unleashes a hideous evil from the dungeons of Castle Meinster, one which follows her to her new assignment. Marianne's depraved new suitor threatens her very soul, until Professor Van Helsing (Peter Cushing) arrives to even the odds. This early entry in Hammer Films' famous horror cycle balances sumptuous Gothic atmosphere with full-tilt vampire action, and remains a fan favorite to this day.

David Robson holds a degree in theatre from the University of Virginia. He worked at YBCA for several years, during which time he programmed series of films by Phil Karlson and Alex Cox. He currently serves as Editorial Director for Jaman, a website that offers users a smarter search for movies online. He also blogs at the House of Sparrows.

BAN7's core idea is to decentralize the curatorial process, and centralize the public presentation of some of the most exciting artistic voices in the region today. As a common shared site for the presentation of works, BAN7 aims to create a lucid web of creative activity in the Bay Area. Their vision is to create a platform for new work and experimentation rooted in the belief that a decentralized curatorial process will open up an opportunity for a wider range of voices and create spaces for dialogue beyond the arts.

In conjunction with BAN7's core curatorial initiative, Joel Shepard, YBCA's Film / Video Curator assembled this Summer's film program "Invasion of the Cinemaniacs" to inflect that initiative. As he states it in his curatorial statement: "When I took this job at YBCA over 15 years ago, I decided immediately that I would not be the only curatorial voice that got to be heard in our Screening Room. I knew very well what a smart and engaged film community we had here, and knew it would be a big mistake to try to speak for all those individuals and communities. My solution then was to make partnerships with a great number of local media organizations, who would host weekly or monthly screenings here. These included groups such as the SF Jewish Film Festival, Film Arts Foundation, Cine Acción, Frameline, Goethe-Institut, San Francisco Cinematheque, and many more. Some of these groups are now long gone, some are alive and well. And some still do regular screenings here.

" 'Invasion of the Cinemanaics!' presented as part of BAN7, is really an extension of this original impulse, but takes it to a deeper, different level. There is a community in San Francisco of avid cinephiles. You might not know their names, but you've seen them around. Some of them write excellent blogs about the local film scene. I wanted to celebrate these folks, who are so strongly invested in local film exhibition, but generally don't get to have a say in what actually gets screened. I realized I could take this idea a little further, and reach out into the world of film criticism, publicity, and other areas where people were building communities around screenings, like Meetup groups.

"I asked everyone to choose a film of special significance to them, without any restrictions. We only had enough slots for ten people (plus one super-sized sidebar event presented by Jesse Hawthorne Ficks), but we could have had a lot more. Many great, dedicated people got left out—for now. But, this was such fun to put together we will definitely do it again, so stay tuned. And the film program, taken as a whole, is amazing. We've got an incredible diversity of some very rare, stunning films. Where else would you find classic Korean cinema next to Mexican psychodrama, alongside Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Bronson, and camp icon Maria Montez? Join us for this unique experiment in film curating."

Imagine my delight in being invited to be among the first wave of "cinemaniacs" to offer a film to this significant, brave program. As a former anthropologist, urban models of the core and periphery have long captured my imagination and my intellect and—in many ways—my current lifestyle of frequently shifting between the San Francisco Bay Area and my (now relatively) new home in Boise, Idaho has been living practice of how cultural flows operate and traffic. By what I have offered the Bay Area over the last decade through entries on The Evening Class, I understand that I will always be recognized as a San Franciscan, even if I reside somewhere else, and Joel Shepard's invitation to join the Cinemaniacs series was respectful confirmation of that. My only regret is that I'm unable to catch all of the series in person, though I will fortunately be able to catch several.

|

The Hole by Tsai Ming-liang,

Courtesy Celluloid Dreams

|

In the early '70s, Karen Larsen founded Larsen Associates, a public relations firm specializing in independent feature and documentary films, film festivals, and special events.

|

The Company by Robert Altman,

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

|

Brian Darr was born and raised in San Francisco and currently works in the San Francisco Public Library's audiovisual department. In 2005 he founded the blog Hell On Frisco Bay, and has been highlighting local film screenings there (and more recently on Twitter as @HellOnFriscoBay) ever since. He's also written essays for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Senses of Cinema, Fandor, and the 2013 book World Film Locations: San Francisco.

Here is the remaining schedule:

|

Colorado Territory by Raoul

Walsh, Courtesy Warner Bros

|

Jonathan L. Knapp has spent nearly a decade in the local film community, whether through writing for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, or working for film festivals such as the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival and Frameline. After several years at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Knapp came to YBCA, where he has worked for the past three years as Film / Video Curatorial Assistant. Simultaneously, he completed an MA in cinema studies at San Francisco State University, and is leaving his position at YBCA this summer to pursue doctoral work in film and visual studies.

|

Death Wish 3 by Michael Winner,

Courtesy Park Circus

|

Cheryl Eddy is the Senior Arts and Entertainment Editor at the San Francisco Bay Guardian, where she has worked since 1999. She holds an MA in cinema studies from San Francisco State University and is a member of the San Francisco Film Critics Circle.

|

Madame Freedom by Han Hyeong-mo,

Courtesy Korean Film Archive

|

Adam Hartzell has been writing for the premier English-language website on South Korean cinema, Koreanfilm.org, since 2000. He has been published in The Cinema of Japan and Korea (Wallflower Press) and Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (Intellect Books). He has written often about the films of Hong Sangsoo, and recently presented a paper on his work at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

|

Hell Without Limits by Arturo

Ripstein, Courtesy IMCINE

|

|

The Exile by Max Ophuls,

Courtesy Universal

|

David Wong writes: "I first began to take film seriously during a 1979 Francois Truffaut retrospective at the UC Theatre, Berkeley and have been attending local screenings with near full-time intensity since about 1980. I remain indebted to Professor Kaja Silverman, whose film theory classes at Cal in the early 1990s helped fill in the gaps created by mere film-viewing alone, and also to Max Ophuls, whose detached yet acutely-sensitive renderings of profound human emotion serve as a constant reminder of what is most valuable about cinema."

|

Pietà by Kim Ki-duk, Courtesy

Drafthouse Films

|

As organizer of The Red Lantern: Bay Area Asian Cinephiles, the world's largest Meetup for Asian films, Alby Lim hosts Asian film events in San Francisco and beyond.

|

Little Fugitive by Morris Engel,

Ruth Orkin, & Ray Ashley,

Courtesy The Film Desk

|

Local film-goer Lynn Cursaro also curates 16mm treasures at SF's Oddball Archive, where she's on the lookout for wacky educational films and '30s curios. A staunch believer in film, she does not own a DVD player nor does she "stream."

|

The Brides of Dracula by

Terence Fisher, Courtesy

Universal

|

David Robson holds a degree in theatre from the University of Virginia. He worked at YBCA for several years, during which time he programmed series of films by Phil Karlson and Alex Cox. He currently serves as Editorial Director for Jaman, a website that offers users a smarter search for movies online. He also blogs at the House of Sparrows.

Saturday, July 12, 2014

FANTASIA 2014—OPENING & CLOSING NIGHT FILMS

In its 18th edition, the Fantasia International Film Festival returns to Montreal's freshly renovated Concordia Hall Cinema July 17 through August 5, 2014, offering a whopping three weeks of World, International, North American and Canadian premieres spanning a panoply of genres.

French cartoonist Riad Sattouf's Jacky au royaume des filles (Jacky in the Kingdom of Women, 2014) [official site] opens the festivities. Drawing from his Syrian background, Sattouf's Jacky satirically upends the Cinderella story by visiting the Kingdom of Bubunne, where women are in power while men wear veils and do domestic tasks. Jacky (Vincent Lacoste)—a lovely young man who dreams of marrying the "Colonelle" (Charlotte Gainsbourg)—is the Cinderfella struggling to realize his dreams in Sattouf's imaginary iron-fisted matriarchy.

Boasting its World Premiere at Rotterdam, Jacky won that festival's esteemed MovieZone Award, joining the ranks of such notable films as Catherine Breillat's Fat Girl (2001), Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis (2007), Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire (2008), and Xavier Dolan's I Killed My Mother (2009), to name a few. Twitch contributor Kees Geuze dispatched that the film's inversion of gender roles provided several hilarious situations, spoofing not only traditional male/female relations but also authoritative dictatorial rule. Geuze likened the People's Republic of Bubunne to North Korea with, of course, the main difference being that the Supreme Leader of Bubunne is a woman. At the Rotterdam Q&A, Vincent Lacoste recounted that he prepared for his role by allowing the younger women in the cast to use him as a slave. At The Hollywood Reporter, Jordan Mintzer characterized Jacky as "parts Cinderella and Barbarella, with lots of Zucker Bros.-style zaniness tossed in." In his Fantasia capsule, Simon Laperrière offers: "In these heavy times filled with bad news in which the very mention of values make people fume, we were in dire need of some acidic criticism of this unfortunate collective situation to bring things back into focus. The hilarious Jacky au royaume des filles has arrived just in time."

The festival will close with the North American premiere of Abel Ferrara's Welcome to New York (2014), the controversial latest from the legendary filmmaker behind such landmarks as King of New York (1990), Bad Lieutenant (1992), 4:44 Last Day on Earth (2011) and the recently re-released Ms. 45 (1981). Welcome to New York is loosely based on the Dominque Strauss-Kahn scandal and stars the iconic Gérard Depardieu in one of the bravest performances of his career. Co-starring is the equally sensational Jacqueline Bisset. Abel Ferrara will be on hand to host this special evening, unveiling his audacious and bold new classic for its first appearance on this continent after explosive bows at Cannes (out of official selection) and Edinburgh. For an extensive recap of this "fraught study of addiction, narcissism and the lava flow of capitalist privilege", I recommend David Hudson's aggregate of reviews at Fandor's Keyframe Daily.

The festival is also presenting two lifetime achievement awards, the first for Mamoru Oshii (accompanied by a remastered presentation of Ghost in The Shell, 1995) and the second for "fear pioneer" Tobe Hooper (accompanied by a remastered 4K presentation of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1974, celebrating its 40-year anniversary). Scoring another coup, there will also be a special screening of James Gunn's much anticipated Guardians of the Galaxy on offer during the festival.

French cartoonist Riad Sattouf's Jacky au royaume des filles (Jacky in the Kingdom of Women, 2014) [official site] opens the festivities. Drawing from his Syrian background, Sattouf's Jacky satirically upends the Cinderella story by visiting the Kingdom of Bubunne, where women are in power while men wear veils and do domestic tasks. Jacky (Vincent Lacoste)—a lovely young man who dreams of marrying the "Colonelle" (Charlotte Gainsbourg)—is the Cinderfella struggling to realize his dreams in Sattouf's imaginary iron-fisted matriarchy.

Boasting its World Premiere at Rotterdam, Jacky won that festival's esteemed MovieZone Award, joining the ranks of such notable films as Catherine Breillat's Fat Girl (2001), Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis (2007), Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire (2008), and Xavier Dolan's I Killed My Mother (2009), to name a few. Twitch contributor Kees Geuze dispatched that the film's inversion of gender roles provided several hilarious situations, spoofing not only traditional male/female relations but also authoritative dictatorial rule. Geuze likened the People's Republic of Bubunne to North Korea with, of course, the main difference being that the Supreme Leader of Bubunne is a woman. At the Rotterdam Q&A, Vincent Lacoste recounted that he prepared for his role by allowing the younger women in the cast to use him as a slave. At The Hollywood Reporter, Jordan Mintzer characterized Jacky as "parts Cinderella and Barbarella, with lots of Zucker Bros.-style zaniness tossed in." In his Fantasia capsule, Simon Laperrière offers: "In these heavy times filled with bad news in which the very mention of values make people fume, we were in dire need of some acidic criticism of this unfortunate collective situation to bring things back into focus. The hilarious Jacky au royaume des filles has arrived just in time."

The festival will close with the North American premiere of Abel Ferrara's Welcome to New York (2014), the controversial latest from the legendary filmmaker behind such landmarks as King of New York (1990), Bad Lieutenant (1992), 4:44 Last Day on Earth (2011) and the recently re-released Ms. 45 (1981). Welcome to New York is loosely based on the Dominque Strauss-Kahn scandal and stars the iconic Gérard Depardieu in one of the bravest performances of his career. Co-starring is the equally sensational Jacqueline Bisset. Abel Ferrara will be on hand to host this special evening, unveiling his audacious and bold new classic for its first appearance on this continent after explosive bows at Cannes (out of official selection) and Edinburgh. For an extensive recap of this "fraught study of addiction, narcissism and the lava flow of capitalist privilege", I recommend David Hudson's aggregate of reviews at Fandor's Keyframe Daily.

The festival is also presenting two lifetime achievement awards, the first for Mamoru Oshii (accompanied by a remastered presentation of Ghost in The Shell, 1995) and the second for "fear pioneer" Tobe Hooper (accompanied by a remastered 4K presentation of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1974, celebrating its 40-year anniversary). Scoring another coup, there will also be a special screening of James Gunn's much anticipated Guardians of the Galaxy on offer during the festival.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)