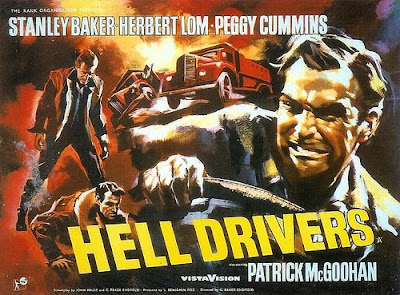

Continuing their tribute to Peggy Cummins, Noir City offered two vehicles from 1957: Cy Endfield's Hell Drivers and Jacques Tourneur's Curse of the Demon (aka Night of the Demon). Alan K. Rode—who I interviewed at Noir City 6 upon the publication of Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy—provided the introduction to both films.

When Eddie Muller first phoned Rode to advise that the Film Noir Foundation (FNF) was flying Peggy Cummins out for Noir City, Rode encouraged FNF to consider Hell Drivers. Through the auspices of Noir City programmer Anita Monga, they were able to reach out to Park Circus to secure a print from the U.K.

For Rode, Hell Drivers epitomizes the word "gritty", literally gritty, grinding, testosterone-filled, edge-of-your-seat, and sure to have you gripping your chair. A signature post-war British film that's uncompromisingly tough and violent, Cummins' co-star Stanley Baker was the perfect fit. One author described Baker as "the British version of Jack Palance" with a face clenched like a fist; but, there was a lot to Baker. He had grown up in a coal mining family in South Wales and was an authentic tough guy. His father had lost a leg in a coal mine. Baker's upbringing influenced his character Tom Yately in Hell Drivers—a guy who just got out of jail for a crime gone wrong, suffering from a lot of guilt, and looking to start over with a new job hauling ballast. What Yately doesn't realize is that he has left a tough and uncompromising prison world only to enter another world that is hypercompetitive, brutal, corrupt and violent.

But when he shows up to hire on, who wouldn't take a job where his initial interview is with Peggy Cummins wearing a pair of blue jeans? Let alone that the cast for Hell Drivers is a who's who of British cinema in the 1960s. In addition to Stanley Baker, the film's testosterone is supported by Patrick McGoohan playing an all-time villain ("and you'll wonder how the cigarette never falls off the edge of his lip"), Sean Connery, Gordon Jackson and the late great Herbert Lom.

From a directorial perspective, Hell Drivers is equally significant for having been written and directed by Cy Endfield, who likewise helped write the script for Night of the Demon, as well as writing and directing the upcoming Noir City entry Try and Get Me!

Endfield grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. His father lost everything during the Depression. He studied drama at Yale, was associated with the Communist Party for a time, then went to Hollywood where he was hired by Orson Welles' producer. Endfield had met Orson Welles in a magic shop because—in addition to being a writer and a nascent filmmaker—he was also an inventor, eventually inventing the world's smallest typewriter. He worked with Welles because Welles' producer said Endfield was the only one who could play a magic trick on Welles and make him look silly.

Endfield started in the MGM shorts department where he produced a significant short entitled Inflation (1942) about American companies gouging people during the war effort. The short was acclaimed but then quickly withdrawn and Endfield was labeled as unreliable. He drifted into B films, shooting several Joe Palooka films (which established his relationship with Hal. E. Chester) and then made The Underworld Story, which was quite a significant film in 1950 starring Dan Duryea. He then made Try and Get Me! (aka The Sound of Fury), by which time he had secured a passport to leave the country for a trip to England. When his passport expired and he went to get a new one the government basically told him, "We don't like you. We're not going to give you a passport." So he found himself unemployed in England, unable to return to his home country, and began doing uncredited writing gigs through assumed names, including Night of the Demon.

By 1956-1957, the Hollywood Black List had started to cool down and Hell Drivers became the first film Endfield had made since 1950 where he could actually put his name on the title. Interestingly, Stanley Baker made six pictures with Endfield and four with Joseph Losey. As ex-patriates working in Britain, both Endfield and Losey had a perspective upon Britain, the people, the time, the post-War culture, that other English directors did not have.