Way back in April, just prior to the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF), local film writer

Johnny Ray Huston posted an interesting list of 50 films and videos on the

SF Bay Guardian Arts & Culture Blog. They were all works which—for one reason or another—had yet to play the Bay Area. Being a compulsive list-maker myself, and one who feels personally slighted when films I want/need to see bypass our local theaters and festivals, I set about compiling my own home-town tabulation of deprivation. Four months later, I realize it's gotten to be now-or-never time. With Venice and Toronto about to begin, I'll be needing a list that's a helluva lot longer than 50 if I wait any longer.

Most of these films were made during the past two years, and none had their world premieres later than this past January's Big Three: Berlin, Rotterdam and Sundance (meaning there's nothing from this year's Cannes.) Also, none have been released on Region One DVD, to the best of my knowledge. Perhaps a dozen are films I've already seen outside the Bay Area, either at the Palm Springs International Film Festival, or during two vaguely recent film-going jaunts to Paris. They're on the list because I want my Bay Area movie buddies to have the chance to (hopefully) enjoy them as much as I did.

I'm aware that a number of these 50 films have received perfectly God-awful reviews, which may help explain why we haven't seen them. But when it comes to directors, actors, subject matter or countries of origin that interest me, I usually prefer to seek out the bad and ugly, as well as the good, and then judge for myself.

A list like this will of course have an extremely short shelf life. With the Mill Valley and Arab Film Festivals in October, and the Latino and 3rd i Festivals in November, I'm optimistic that at least a few of these films will soon be coming our way. I anticipate that our local cinemas and rep houses will also do their part. Just days ago I learned that two films originally on the list, Aki Kaurismäki's

Lights in the Dusk and Bahman Ghobadi's

Half Moon, will be screened at the Pacific Film Archive (PFA) in October.

Finally, you'd think that living in second best place in the nation for cinephiles would leave one with little or nothing to complain about. You would be wrong. So without further ado…

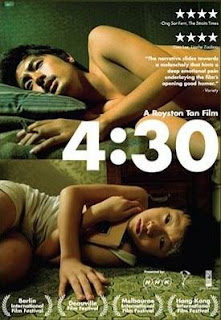

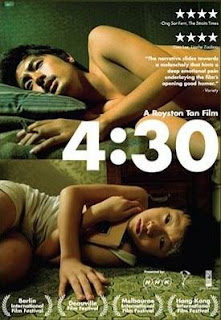

4:30

4:30—Singapore director Royston Tan's follow-up to

15, which was one of my 10 favorite films of 2004. I foolishly passed on seeing this at Palm Springs, certain that the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival (SFIAAFF) would bring it to us this spring.

Abeni—In 2005, the PFA had an evening of films from Nollywood, the nickname given to Nigeria's burgeoning video industry. One of the highlights of that program was Tunde Lelani's

Campus Queen, and this is his latest.

Alatriste

Alatriste—The most expensive Spanish-language film ever made, starring Viggo Mortensen as a 17th century army captain. Nominated for 15 2006 Goya Awards.

Alexandria . . . New York—81-year-old Egyptian director Youssef Chahine is considered by many to be the greatest Arab filmmaker of all time. His latest film

Chaos, is set to premiere at Venice this year. Meanwhile, I'd sure like to have a look at this feature from 2004.

Armenia (Le voyage en Arménie)—The latest from Marseilles auteur Robert Guédiguian, whose working class dramas (

Marius and Jeannette,

The Town is Quiet) frequently star his wife, the sublime French actress Ariane Asacaride. The SFIFF brought us

The Last Mitterrand in 2005, but the Bay Area has also yet to see 2002's

Marie-Jo and her Two Lovers and 2004's

My Father is an Engineer.

Bad Spelling (Les fautes d’orthographe)—Teenagers run amok in a French boarding school, with Olivier Gourmet and Carole Bouquet as headmaster and mistress. One of many French films on this list, proving the necessity for a Bay Area version of New York's "Rendez-Vous With French Cinema", or LA's "City of Angels/City of Light".

Blame it on Fidel (La faute à Fidel)

Blame it on Fidel (La faute à Fidel)—A nine-year-old girl finds her world turned upside-down when her parents become leftist radicals in early 1970s Paris.

Carnaval of Sodom (El Carnaval de Sodoma)—Mexican master Arturo Ripstein's first narrative feature since 2002's

The Virgin of Lust.

Close to Home (Karov La Bayit)—A film about the experiences of two teenage girls serving in the Israeli military. This played in dozens of US festivals earlier this year and was a surprising omission at last month's SF Jewish Film Festival.

Cobrador: In God We Trust—Mexican director Paul Leduc's anti-globalization tale starring Peter Fonda. I confess to not having seen a Leduc film since 1986's haunting

Frida, naturaleza viva.

The Consequences of Love (Le conseguenze dell'amore)

The Consequences of Love (Le conseguenze dell'amore)—Paolo Sorrentino's debut film about a Mafia hit man holed up in a Swiss resort hotel was one of the best received films of Cannes 2004. It was subsequently a box office success in Europe, but never registered in the States (not even at our own annual New Italian Cinema series). It appears that his 2006 follow-up,

A Friend of the Family, will suffer a similar fate.

Container—Swedish director Lukas Moodysson (

Lilya 4-ever,

A Hole in My Heart) takes a break from reminding us what a horrible, brutal world we live in and tries his hand at something truly experimental.

El Custodio

El Custodio—Argentina continues to make some of the most urgent and interesting cinema in the world. This film by Rodrigo Moreno was one of the hits of this year's New Directors/New Films series in NYC.

Destricted—This collection of seven erotic shorts from the likes of Gaspar Noe, Larry Clark and Mathew Barney played at Sundance and Cannes in 2005 and then completely disappeared.

Day Night Day Night—Julia Loktev's controversial accounting of a young woman's final hours as a Times Square suicide bomber didn't make much of an impression on me when I saw it at Palm Springs. Still, it deserves to be seen by Bay Area audiences. If Salt Lake City, Santa Fe, Milwaukee and Atlanta have seen it, why haven't we?

Drama/Mex—This Acapulco-set teen drama has been called the Mexican version of

Kids.

Gift From Above (Matana MiShamayim)

Gift From Above (Matana MiShamayim)—Dover Koshashvili had a nice festival/arthouse success with his 2001 film

Late Marriage, set within the Georgian community in Israel. As far as I know, his next film has never been seen in North America. I saw it in Paris in 2005, loved it and would jump at the chance to see it with English subtitles.

The Great World of Sound—One of the few Amerindies at Sundance this year to pique my interest, it's about phony record producers who travel the country bilking gullible amateurs.

I'm a Cyborg, but That's OK (Saibogujiman kwenchana)—The new Park Chan-wook.

In the Pit (En el hoyo)—This Mexican documentary about the construction of a super-highway was featured in Landmark Theater's Spring

FLM magazine, but has yet to be released. I saw it at Palm Springs and was underwhelmed, but I'd happily sit through it again to re-experience that jaw-dropping finale.

Invisible Waves

Invisible Waves—I have a feeling we'll be seeing Pen-ek Ratanaruang's newest film from this year's Cannes (

Ploy) before we'll see this poorly-received film from Berlin 2006. This is another one I passed on at Palm Springs, certain it would play one of the Bay Area's spring fests.

Johanna—I've heard both awful and fantastic things about this 2005 filmed opera set in a mental hospital, which was produced by Bela Tarr.

Ken Park—I saw this Larry Clark shocker at a Parisian multiplex in 2003 and can sort of understand why it was never released in the US, either in theaters or on DVD. Two particularly outrageous scenes are the stuff of legend. I've heard rumors of a clandestine invitation-only screening at the Castro several years ago.

Khadak—A young nomad makes a shamanistic journey across the frozen steppes of Mongolia in this Sundance 2007 Grand Jury Prize winner.

The Last Communist (Lelaki komunis terakhir)

The Last Communist (Lelaki komunis terakhir)—In 2005 the SFIFF had a wonderful side-bar on New Malaysian Cinema, but they've neglected to follow through. All of the directors in that sidebar have since released new films, but with the notable exception of Yasmin Ahmad, none have been seen in the Bay Area. This is one of two films by Amir Muhammed that I'm quite anxious to see (the other is 2007's

Village People Radio Show.)

Life is a Miracle (Zivot je cudo)—Something's truly wrong when a two-time Palm d'Or winner like Emir Kusturica makes a film and we don't get a chance to see it. Fortunately, I had the pleasure of catching this Cannes 2004 entry in Paris two years ago (albeit with French subtitles), and wonder if I'll have to return to Paris in order to see his film from this year's Cannes,

Promise Me This.

Mary—Abel Ferrera's 2005 contemporary take on the Mary Magdalene legend. Again, I have a feeling we'll be seeing his latest work, Cannes 2007's

Go Go Tales, before we get the opportunity to see this.

The Matsugane Potshot Affair (Matsugane ransha jiken)—A new film from Nobuhiro Yamashita, director of the fabulous

Linda Linda Linda.

Never Forever—Another 2007 Sundance Amerindie that sounded interesting. Vera Farmiga is married to an infertile Korean-American husband, and to save their marriage ends up taking an unusual path to pregnancy.

No Place Like Home—Perry Henzell's 30-year-old, finally-completed follow-up to 1972's

The Harder They Come had its world premiere at Toronto last year. Two words . . . Grace Jones!!!

OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies (OSS 117: Le Caire nid d'espions)—French comedies are rarely my thing, but this stupid/smart retro spy film was one of the most enjoyable experiences I had at Palm Springs. I wrote more about it

here.

The Other (El Otro)

The Other (El Otro)—From Argentine director Ariel Rotter, this year's Silver Bear winner from Berlin.

Paraguayan Hammock (Hamaca Paraguaya)—This difficult, but intriguing bit of minimalism by Paz Encina is the last of the New Crowned Hope films waiting to make an appearance in the Bay Area. I saw it at Palm Springs, and would gladly take a second look.

The Pool—Documentary filmmaker Chris Smith (

American Movie,

The Yes Men) makes his narrative feature debut with this Goa-set tale about class distinctions.

Rain Dogs (Tai yang yue)

Rain Dogs (Tai yang yue)—More independent Malaysian cinema from Ho Yuhang, director of 2004's

Sanctuary.

Retribution (Sakebi)—This is the latest film by prolific Japanese creep-meister Kiyoshi Kurosawa that has yet to come our way (we're also waiting for 2005's

Loft). Both were ignored by the SFAIFF and the SFIFF, which surprised me in light of their previously strong support of his work.

Right of the Weakest (La raison du plus faible)—The latest from Swiss actor/director Lucas Belvaux, director of 2002's ground-breaking Trilogy (

On the Run,

An Amazing Couple,

After the Life).

Les Saignantes—Opportunities to see contemporary, home-grown African films in the Bay Area are increasingly rare these days. Even this year's New African Cinema series at the PFA consisted of a meager four features. That said, I still have hopes of someday seeing this 2005 feminist sci-fi tale from Cameroon.

Southland Tales

Southland Tales—Richard Kelly's much-anticipated follow-up to

Donnie Darko was considered to be THE disaster of Cannes 2006 (and was at the top of Huston's list of 50 films). Rumor is that some version of it will arrive in theaters later this year.

Still Life (Sanxia haoren)—This 2006 Venice Golden Lion winner from Chinese director Jia Zhang-ke was perhaps the most glaring omission from this year's SFIAAFF and SFIFF. When we finally see this, it will hopefully be accompanied by the film's related documentary,

Dong.

Tachigui: The Amazing Lives of the Fast Food Grifters (Tachiguishi retsuden)—The latest animated feature from Mamoru Oshii (

Ghost in the Shell).

Takva: A Man's Fear of God—This Turkish film about the personal hypocrisy a devout Muslim faces when his lot in life suddenly improves has garnered raves at every festival it's played.

Taxidermia

Taxidermia—György Pálfi's (

Hukkle) fabulously disgusting allegory on recent Hungarian history would have been such a natural programming choice for the SFIFF's Late Show series, SF Indiefest or the recent Dead Channels festival. Yet another reason I'm glad I went to Palm Springs.

Time (Shi gan)—Kim Ki-duk's 2006 plastic surgery parable. His latest film, Cannes 2007's

Breath, also waits in the wings.

To Get To Heaven First You Have To Die (Bihisht faqat baroi murdagon)—This sly, little black comedy from Tajikistan suggests that perhaps murder is the ultimate aphrodisiac. Another film from Palm Springs and one of my favorites of the year so far.

Transylvania—Perhaps Asia Argento's stature as Queen of Cannes 2007 (with films by Abel Ferrera, Catherine Breillat and Olivier Assayas) will help get this 2006 Tony Gatlif film released. My write-up from Palm Springs is

here.

Tuya's Marriage (Tuya de hun shi)

Tuya's Marriage (Tuya de hun shi)—Chinese/Mongolian Berlin Golden Bear winner about a disabled married woman's search for a new husband.

The Untouchable (L'intouchable)—Isild le Besco re-teams with director Benoît Jacquot (

À tout de suite) for this story of a young woman who travels to India in search of her father.

VHS–Kahloucha—This Tunisian documentary about a prolific amateur filmmaker got raves at Sundance and elsewhere.

Welcome Europa—Bruno Ulmer's stylized documentary about male immigrants literally prostituting themselves in order to survive in today's Europe.

Introductory illustration courtesy of

Brian White.