I've been watching movies in the Castro Theatre since 1975. Even after 30 years, I never take for granted the Castro's palatial embrace, its Mighty Wurlitzer, its huge screen, the electric receptivity of its audiences (or its hissing snakepits), the variant festivals it hosts, and the countless onstage events that have helped create the texture of cinematic history in San Francisco. I know—as a cineaste—that I am blessed and I am cognizant and proud of that blessing.

Over the years there have been many times when on stage tributes have accompanied programmed films and I've sat near enough the honored guest to watch them watch themselves in films of yesteryear. It fascinates me for some reason, this observed distance between then and now. Watching Cyd Charisse enjoy herself in Silk Stockings. Sitting right next to Kenneth Anger as Frameline celebrated his early experimental films. And Friday evening right across the aisle from Marsha Hunt, her elegant face tilted slightly back as she monitored her youth in Raw Deal and Kid Glove Killer. What was she thinking? Has the aesthetic of ephemerality ever been more poignant than when considering the loss of one film noir print after another, and the youthful energy that fueled them? She was happy, that seemed clear, and proud undoubtedly. I had her autograph generously scrawled on my folded program and, after Raw Deal, sat back with attentive pleasure to hear her converse with Eddie Muller.

* * *

Marsha Hunt: I can't get over this. [Responding to her standing ovation.]

Eddie Muller: And I'm here to tell you that, yes, she does look that good close-up.

Hunt: I have to tell you, I have done three plays in San Francisco. I've never ever come across audiences as good as San Franciscans. [Cheering applause.]

Muller: I have to ask you—did you see this picture [Raw Deal] when it first came out in the 1940s? Did you even bother to go see it?

Hunt: I did.

Muller: Do you have any recollection of [making it?] I ask that as kind of a little joke because a lot of these pictures were "B" pictures. Raw Deal was definitely a "B" picture. …We could talk a little bit about Edward Small, the producer, who was really one of the giants of independent film production in Hollywood … but, at the time, did you happen to think when you were cast in this movie, "Boy, this is really a potboiler. Is this going to do anything for my career?"

Hunt: It's about as negative as a story can get.

Muller: That's why we love it!

Hunt: They hadn't coined that term "noir" yet and it was a very strange kind of film. You weren't sure who—if anyone—you could pull for. But it was a gorgeous cast. I loved working with all of them. No, we had no idea it was going to be destined—how many years later?—that was 1947. That was 60 years ago. Who knew that we would be in the vanguard of something that would become a cult? A movement? [Staring out at her audience, Hunt sweeps her arm to include everyone.] Look at you! I have puzzled over the years as this movement grew: what is it exactly that they love? Nobody to pull for. Virtue is not rewarded. You love shady ladies and I am Miss Virtue. Except, the interesting thing is, Claire [Trevor] is the bad girl, she's in love with a bad guy, and she winds up making the supreme sacrifice so that love can conquer all. And Miss Virtue winds up aiming a gun and firing. So you figure.

Muller: That's why everybody's here tonight.

Hunt: And you know it did occur to me—because I really puzzled over [this]—why does everyone love this kind of story? Mayhem and flames and have you ever noticed there is no dry street at night? They're always soaking wet. Photogenic, I agree, but I think the reason everybody loves noir films is that it gets as bad as it can get up there and you go home saying to yourself, "Well, I guess my life isn't really that bad after all."

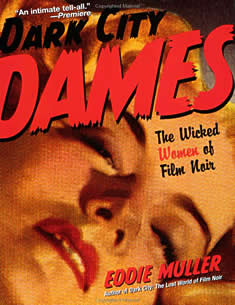

Muller: I do have to tell you one really funny story about this. Several years ago I did a book called Dark City Dames and it was my sincere hope that Claire Trevor was going to be one of the dames that I wrote about. I had several interviews with Claire on the telephone and she just wasn't in good enough health to actually participate. But I talked to her about Raw Deal. In absentia we'll tell this Claire story. She didn't remember it, is the whole point. I said, "So tell me about Raw Deal" and she said, "What's that?" She said, "Just remind me of it. It will come back to me." I said, "Oh, Dennis O'Keefe is the guy. There's a little twist. He's the homme fatale between the bad girl and the good girl." She said, "Oh. Who else was in it?" I said, "Well, Marsha Hunt…." She goes, "The good girl, no doubt?" [Laughs.] So at what point in your career did you realize you were fated to be cast as "the good girl"? And was that okay with you?

Hunt: I wasn't always. I moved around a bit. In fact, Metro—which I had just left when we did Raw Deal—let me play no two people alike and that was the happiest, imaginable [thing]. I was good. I was bad. I was inbetween. And it was all wonderful. I was frequently old. I played four old ladies in movies before I was 30. That was a tremendous compliment that they thought I could do that convincingly. So that was the joy for me—not playing good or bad—but playing every possible kind of person.

Muller: You did have a reputation as the best-looking character actress in Hollywood.

Hunt: I was called the youngest character actress except for those four old ladies I played.

Muller: How did you start? I heard you say that you wanted to be an actress from the time you were about 3-4 years old. What was your course to Hollywood? You were born in Chicago, right?

Hunt: How long do you have? It's quite a story and I think you probably want to go over other things. I tricked Hollywood into signing me and it worked.

Muller: How so? I want to know the trick. Tell us the trick.

Hunt: I was fashioning my own road into movies. Oddly enough, I was movie struck, never stage struck, and I grew up in New York a few dozen blocks from Broadway. But I saw a lot more movies than I did plays. You could afford them more. And it was the Depression. When I finished high school, it was of course expected that I would go to college as my parents had done, and my sister was already in college, and I found there was not a college in the country where you could major in drama before your third year. I didn't want to spend two years studying everything except what I wanted to do with my life. So I didn't go to college, broke my parents' hearts, stayed in New York. There was no training for movies, none. There wasn't a single course on any kind of film to be had. So I fashioned my own approach, which was to be a model, learn about cameras and lights and make-up and grooming and all that. Find out if I photographed or not. Talkies had come in so I marched down to NBC and had a series of auditions—I was 16 at the time, just out of school—to learn about sound and all that. Then I went to dramatic school, since there was no training for films, I went to study about the theater. Two photographers I had worked for as a model had a hunch about me. They moved to California and set up a PR business in Hollywood. They got an idea. They thought, Hollywood is really child-like—not childish, child-like—and that child psychology ought to work. If you tell a child filled with all kinds of food on a plate, "You can eat everything on this plate except the spinach, no spinach," the kid's going to say, "Well, what's wrong with the spinach? Why can't I have spinach? I want spinach!" And that is what happened. They made me spinach and told Hollywood that they couldn't have me and Hollywood insisted on having me.

Muller: I want to talk a little bit about the second film we're going to see tonight—Kid Glove Killer—which is quite a rarity. Boy, this is a real treat that we're getting to see this tonight. Did you think this was a breakthrough film in a sense? It was Fred Zinnemann's first film as a director and it had quite a good part for you as well.

Hunt: It was a lovely role. I don't know if I had already worked with Van [Heflin]—we did three pictures together and I enjoyed them very much; he was a bright, gifted, nice complicated fellow—and Fred Zinnemann is as gifted as they get. Fred was so softspoken, so low-key. We all said, "Who's going to direct this?" and they said, "Fred Zinnemann" and we said, "Fred what?" Nobody had heard the name and he came on the set first day and—before we rehearsed a scene—he asked if everybody could come down from the catwalks up there and from the far places and gather round, because he didn't speak very loudly, and he said, "I wanted to meet you all. As you may well know, this is my first feature film. I think I'm ready. I've been working a long time to be ready. But you are the veterans. You've all made many films. I want this to be the best film we can make and if any one of you, whatever your job, sees a better way to do what we're doing, come and tell me and I'll be very grateful." No one could believe the humility, the decency, the niceness of that, and the respect for the professionalism of gaffers and prop men and make-up men and so on. I think they would have died for him if he asked and he made a very good film. But what a way to start! Wasn't that a good beginning?

Muller: For whatever reason, certain directors like Fred Zinnemann and Robert Wise had great reputations as really humble, competent, craftsmen. They just don't get written about in the same way that the Fritz Langs and the Orson Welles get written about. They just don't have that kind of forceful personality but everybody who has worked with them just sings their praises completely. Zinnemann came over in that same group from Germany, with Preminger and Fritz Lang and Edgar Ulmer….

Hunt: You know it's the only thing that I can think of that we have to be grateful to Hitler for. [Laughter.] The exodus from Europe of these gifted, brilliant filmmakers—thanks, Adolph!

Muller: Marsha! We'll see that quote in The New York Times come Monday morning.

Hunt: Let me just ask, if the audience is in any doubt of the name of the leading man's character in the film we just saw? The name of this guy was: JOE!! I don't think there were two lines in a row that we didn't say his name.

Muller: Speaking of which, any recollections about the great Dennis O'Keefe who I think is really one of the greatest underrated actors? You could put Dennis O'Keefe up against Bob Mitchum in a lot of these roles and it's like, I'm buying this guy completely. He's fantastic.

Hunt: I loved working with him. We had a very good time on the show. I do remember Dennis taught me a very spicy song, which I will not sing for you tonight.

Muller: Wait, we've got time.

Hunt: Claire kind of avoided me. It was not hostile. She just never happened to be near me except in a scene and we never really had much conversation together and I realized along the way she wanted to keep the distance between us so that she would have no problem hating me. What if we got to like each other? That might make it difficult to play. But I never saw Claire again for 30-40 years. And then we met at my across-the-street neighbor's home. He was Burt Kennedy, do you know that name? [Applause.] Burt is gone but I'm sure he thanks you from wherever he is up there in Western Heaven. But Burt gave himself a 70th birthday party every year for 10 years. I went to every one of them because I lived across the street. At one of them, there was Claire Trevor! She greeted me as warmly as she never did while we were shooting the picture. See, it was safe. She didn't have to hate me anymore. She was lovely.

Muller: And by then she owned all of Orange County.

Hunt: I didn't know that.

Muller: Her husband was quite a successful real estate [investor]. …Of all the pictures you've made—I know we're talking noir here tonight—but there must be personal favorites of yours that you would like to see. Raw Deal is back. You can see it on dvd.

Hunt: It's perennial, yeah?

Muller: Are there other films that you've made that you're equally proud of or moreso that you want people to see?

Hunt: There were 62 of them. It's hard to say any particular one. The one in which I had the most fun was Pride and Prejudice. I never got a whiff of playing comedy before Pride and Prejudice and I was ready. The darling director Bob Leonard turned me loose and I got to squint and wear nearsighted glasses. I remember Karl Freund was the camera man and he used to say, "Where's Turkeyneck? Bring Turkeyneck in; we're ready for her", making my neck even longer than it was and sausage curls and singing off-key. If you are at all musical—and I am—it's hard. They coached me for weeks to sing just in the crack, not quite off-key, but inbetween, just enough to hurt the ears. I had a wonderful time. I already had a big crush on Laurence Olivier. What a cast! It was a privilege to be a part of that. I think we knew we were making a classic and it sure is.

Muller: Those of you who came to the reception earlier and the lucky ones who were able to buy a copy of Marsha's book, your book The Way We Wore—which is about fashion from the '30s and '40s and so much more—is one of the most interesting combinations of things I've ever encountered in a book. I've never seen a book that mixes sociology, politics, wardrobe, fashion and hairstyles in quite the way this book does. It's really amazing. Like: just because you're a diehard liberal doesn't mean you can't dress well! If you don't have a copy, you owe it to yourself. Which leads me into: right at the height of your career all of a sudden visitors from Washington appeared in Hollywood and the House Un-American Activities Committee swooped in. [The audience hisses.] Oh, I know where this audience is coming from! You were actually a participant in one of the most remarkable plane trips ever taken. I always say that—if that Hollywood Fights Back charter flight to Washington for the hearings—if that plane had dropped an engine, Hollywood's history would have been entirely rewritten. There were so many amazing people on that airplane. I've set it up. Take it away, Marsha.

Hunt: What's to say about it? I think there were probably several hundred familiar names and faces who would have liked to be on our flight. Hollywood was under attack. There was a Congressional committee called the House Un-American Activities Committee, which found that it could get itself headlines by accusing Hollywood of being masterminded by Communists and that it was really very dangerous to go to the movies because your patriotism might be subverted because there were a lot of Reds writing screenplays, maybe directing them, acting in them. That was what was happening in 1947. Nineteen very gifted writers and directors and one actor were subpoenaed to come to Washington and account for their political beliefs. But we have a secret ballot, I understood. I thought that was one of the things we were promised. So—just on principle—we objected to that. People had a right to be Communist. It was a perfectly legal political party at the time and so for it to be made a hazard to your career and a dirtier word than murder or rape—if you were a Commie, watchout!—for that reason Hollywood stood up and said, "Stop this." We gave—"we", meaning the industy—gave those 19 a send-off meeting at the biggest auditorium in town—the Shrine; it seated 6-7,000 moviemakers; they came from every studio—as the send-off to the Hollywood 19. Those of us who went on the flight were simply those who were free and not shooting at the time but our plane was paid for by the nickels and dimes and dollars of the moviemaking people. We passed the hat. Howard Hughes—hardly a Communist—offered us a plane, one of his many planes, to fly back to Washington.

Muller: That was the one that was supposed to drop the engine.

Hunt: He was not allowed to give it! We had to pay full price so we passed the hat. The industry paid for chartering a flight and there were 30-some of us on the flight and, of course, it was led by the Bogarts. Danny Kaye was probably the other big [name]. John Huston was among the three directors who thought up that trip. See, the headlines were scaring Americans to death that maybe it wasn't safe going to the movies anymore, their loyalty might be subverted by hidden Commie propaganda tucked away in the dialogue. This was such nonsense that it had to be answered. But the headlines were very large and the Committee—which included Richard Nixon, he was on that committee [the audience hisses]—they had the answer. They were getting headlines every day on the strength of the attack on Hollywood. So this was fighting fire with fire; headlines with headlines. …Anyways, we flew to Washington to accentuate the positive. We stopped along the way at two or three stops on the way there and two or three stops on the way back. The word was out about our flight. The flying field was packed with citizens. They didn't care about Communism or the hearings, they wanted to see the Bogarts. They wanted to see all those movie stars. So we spoke to the public that thronged these flying fields at every stop and explained our mission, that it was pretty hard to subvert Americans' loyalty without being caught at it. If there were Communists that wanted to get some propaganda tucked away, there were too many cooks making that soup of a movie—all the way from the head of the studio to the editor to the producer to the sneak previews, all of those—you couldn't get away with tricking Americans into loving Communism. We had to speak plainly about that, which we did along the way and we did in Washington. We attended two days of hearings of the Hollywood 19, as they were called, these truly gifted men. We were misquoted. We were ridiculed by some of the press. The rest of the press thought we were doing a dandy job of showing the other side of things. Anyway, by the time we got back to Hollywood, the hearings had been called off and we thought maybe we had made a difference. Maybe really we had been able to even the score…. But then there was a meeting at the Waldorf-Astoria held by all the studio heads and that's where it hit the fan. That is where we lost the war. Because the people who provided the funds for movies said, "We are pulling our backing for your studios if you don't get rid of every one of these Hollywood 19 who have been subpoenaed as unfriendly witnesses"—they had already heard some friendly ones—"get rid of them. Get rid not only of the Hollywood 19, get rid of anybody who seems in any way to be making waves. There's money at the box office and we can't lose it." So the Hollywood 19 were summarily fired and we who had spoken up to defend their political freedom were also suspect.

Muller: Do you think that your joining the Hollywood Fights Back Committee For the First Amendment definitely had an effect on your career? Were you, in fact, blacklisted?

Hunt: Oh, yes. That's whatever happened to Marsha Hunt.

Muller: A lot of people draw parallels between that period and some things that are happening today. As someone who lived through it, and is also living through what our country is going through today, do you see those parallels?

Hunt: Yes.

Muller: You do?

Hunt: Conformity is a dangerous word. It means don't think for yourself, go with the safe ticket, the safe viewpoint, don't ask questions, don't make waves. If the public is convinced of that, you've got them and nobody will challenge you. There has been a bit of this, more than a bit, in the last few years. What are we doing over there? [Cheering applause.]

Muller: Next question: will you run?

Hunt: I've twice been asked to run for public office. I was never so flattered but . . . no.

Muller: But you have done a great deal of humanitarian work.

Hunt: Getting blacklisted gave me more free time than [I knew what to do with]. Rather than do several other things that could fill your time, I discovered some things that maybe deserved more attention than they were getting. It felt so good. I went around the world in 1955 with my husband and I came back a citizen of the planet. I decided we were not just Americans, we were part of the whole. I began to want to know more about the rest of it. I looked into the U.N. and that's where the next 25 years of my life went. I decided that was maybe our last best hope and gave it all the attention and time and energy I could. It was the most rewarding period for me. I had a remarkable career. I had made 50 movies by the time I did my first Broadway play. I had had such a rewarding time for this acting bug that bit me at any early age that it was quite wonderful that I had a chance to . . . certainly no ego needed more food than I had been given. It was time to give my attention and energy outside myself. Let's face it, acting is a very self-centered pursuit. Yes, you get to play you're a lot of other people but it's you doing it and it's the public who likes you, if they like what you do. So it was kind of a privilege to be able to turn all of my energies outward and try and explain this great idea of all humanity coming together for once to end war. [Applause.] You may well applaud, [the United Nations] was born here in San Francisco and now it lives on our opposite coast. It is really an American idea that the rest of the world joined with and, yet, the hostility to the U.N. is something so breathtaking. I, by some miracle, got on the nutty Right Wing's mailing list and I get mail that is so shameless. It distorts the U.N. and is out to destroy it and to get the U.S. out of the U.N. and the U.N. out of the U.S. …There are those who don't like the world. They only like the U.S. I think the world is just dandy and we'd better join it. [Cheering applause.]

Muller: Marsha, if you don't want to run for President, I think there's a mayor's slot opening up here in San Francisco….

Hunt: As a matter of fact, I have the key to San Francisco from the then-mayor when I came up here. I heard that the Alcazar Theatre—which was first called the United Nations Theatre because some of the early U.N. sessions were held there—well, I did a play, my favorite play, at the Alcazar Theatre and when I heard that it was going to be torn down, I came up here and demanded to see the mayor to put a stop to this. He said that he agreed with me but he couldn't stop it unless there was a groundswell. So he gave me the key and I went home proudly. They tore down the Alcazar and it's [now] a parking building, isn't it? It parks a lot of cars.

Muller: Sadly, they have changed the locks in this town since you were here. So the keys don't quite work the way they used to. But, y'know Marsha, at the top of the show when I talked about how we enjoy the fact the film noir inspires a new generation of people, the real treat about doing this festival and having guests like you come out here is really to pay tribute to you. It's such a blessing to have somebody of your caliber and your intelligence and longevity to come out here and inspire these young people in this audience.

[At this point Marsha Hunt received a standing room ovation from her cheering capacity Castro crowd.]

Cross-published at Twitch.

04/20/07 UPDATE: Cabinetic at the main Greencine site has posted their video footage of this onstage event.