Jed Rosenthal Bell is a San Francisco filmmaker who started out as a community organizer for ACT UP, queer civil rights campaigns, and FTM International, learning graphic design along the way by making posters and flyers, protest signs and transgender newsletters. Jed wound up combining the collaborative, crowd-orchestrating skills of activism with the visual storytelling of graphic design to start a career as a filmmaker. His first film, the queer noir crime drama Foucault WHO? (made with writer Wickie Stamps), has toured the globe, winning "best of festival" awards in the U.S. and Europe. His second film, the kvetchy animated trans satire DRIVE THRU, is still making its way around the world after winning "Best Animation" at San Francisco's Rough Cut Film Festival.

I was introduced to Jed Rosenthal Bell through his participation with Frameline's Persistent Vision Conference earlier this year, where Matt Florence interviewed him for the Persistent Vision website and where he organized and moderated a panel discussion on Emerging Voices in Queer Cinema. I was struck by his articulate enthusiasm and asked if he'd be up for an interview. Luring him over to my home for ricotta cheese pancakes, we finally got the job done. And what an enjoyable job it was!

* * *

Michael Guillén: Jed, I'm really glad to talk with you. I think you're one of the brightest young talents of queer cinema.

Jed Bell: Aw, thank you.

MG: I'll be honest and say I was a bit cautious watching your films, not quite knowing what to expect, but I was genuinely pleased to find a professional edge to your work, which for me indicates a certain respect for your audiences that many young queer film makers—who are angry and acting out—sometimes forfeit. Your two films—Foucault, WHO? and DRIVE THRU—are strikingly dissimilar and yet both reveal your obvious fascination with genre. Could you speak a bit about that?

MG: I'll be honest and say I was a bit cautious watching your films, not quite knowing what to expect, but I was genuinely pleased to find a professional edge to your work, which for me indicates a certain respect for your audiences that many young queer film makers—who are angry and acting out—sometimes forfeit. Your two films—Foucault, WHO? and DRIVE THRU—are strikingly dissimilar and yet both reveal your obvious fascination with genre. Could you speak a bit about that?Jed: Yeah, I'm just not interested in films that aren't about genre and I didn't even realize that until I heard Joss Whedon speak at a screenwriting expo last year. Do you know who he is?

MG: I don't.

Jed: He's the creator of the t.v. show Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. Also he was the writer of the movie—but that doesn't represent him well—anyway, he's making the new Wonder Woman movie now and he's done various things inbetween. He talked about studying genre studies at Wesleyan in the late '80s. He said he's only interested in making things that are about genre, whether they're in genres or a mix of genres. So he makes sci-fi, horror, westerns, but no movies about "a little girl that had a feeling." I call them "little girl that had a feeling" movies, what San Francisco narrative filmmakers specialize in, including a lot of my friends who are very talented, who I'm not dissing; I'm just not interested in making those kinds of movies. When Whedon articulated this, I thought, "But that's me!" I like crime dramas and satires and some comedies and stuff but I totally don't care about the kind of stuff that the Sundance Film Festival likes to show a lot, like general American landscape and a person having a feeling within it. I'd rather chew my own arm off than make or watch one of those movies. It just doesn't interest me.

Jed: He's the creator of the t.v. show Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. Also he was the writer of the movie—but that doesn't represent him well—anyway, he's making the new Wonder Woman movie now and he's done various things inbetween. He talked about studying genre studies at Wesleyan in the late '80s. He said he's only interested in making things that are about genre, whether they're in genres or a mix of genres. So he makes sci-fi, horror, westerns, but no movies about "a little girl that had a feeling." I call them "little girl that had a feeling" movies, what San Francisco narrative filmmakers specialize in, including a lot of my friends who are very talented, who I'm not dissing; I'm just not interested in making those kinds of movies. When Whedon articulated this, I thought, "But that's me!" I like crime dramas and satires and some comedies and stuff but I totally don't care about the kind of stuff that the Sundance Film Festival likes to show a lot, like general American landscape and a person having a feeling within it. I'd rather chew my own arm off than make or watch one of those movies. It just doesn't interest me.MG: Which surprises and intrigues me. One of my favorite filmmakers is Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a Thai experimental filmmaker, who has altered both local and mainstream genres a lot. I'm also quite fond of Japanese filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa who likewise tweaks established genres like horror and police procedurals and turns them into something else, something unexpected.

Jed: I love that! We actually just watched The Grudge finally from beginning to end a couple of days ago. Have you seen that movie?

MG: The American version?

Jed: The American version. Now I want to see the original. Have you seen it?

MG: Yes, I have.

Jed: It's just this strange movie. I realized I had to really pay attention to it. I had watched the first 20 minutes of it like 10 times and never got caught up in it but I realized you had to sit and pay attention. It's paced differently. It's about something different than the horror movies I usually watch. Yeah, I just love the unexpected emotional relevance of it or whatever. I mean, I love regular horror movies too. I have all these theories about horror movies. They're all about guilt and class fear and the fear of people from outside the cities. They almost always have a framing story—I've never studied this; it's just things I've noticed—but, a classic example is I Know What You Did Last Summer, a fine film, also starring Sarah Michelle Geller. [Chuckles.] Anyway, I find [genre films] much more emotionally relevant for me, I guess.

MG: What strikes me about genre films—and I've already mentioned the efforts of Weerasethakul and Kurosawa—is how they're evolving. Genre films in the past have definitely been entertainment films—westerns, police procedurals, romance melodramas—but I'm noticing several contemporary filmmakers using genre films as platforms for, as you suggest, encoded themes and messages. I felt it quite astute on your part to express some of the most controversial political themes going today through the popular format of genre.

Jed: Thanks. It's just what interests me. I wouldn't pay attention to the movies myself if they didn't have it, do you know what I mean? Like, I really like Memento. To me that's almost a perfect example because it's a thriller, and a mystery, and crime drama, but it's secretly about something important and deep and that's the only way I want to hear about it. We're American narrative filmmakers—that's what we're good at, is showing people a good time—let's use that to trick ourselves and other people into learning something.

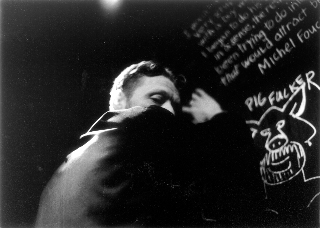

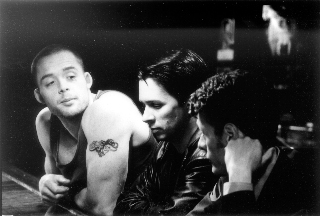

Jed: Thanks. It's just what interests me. I wouldn't pay attention to the movies myself if they didn't have it, do you know what I mean? Like, I really like Memento. To me that's almost a perfect example because it's a thriller, and a mystery, and crime drama, but it's secretly about something important and deep and that's the only way I want to hear about it. We're American narrative filmmakers—that's what we're good at, is showing people a good time—let's use that to trick ourselves and other people into learning something.MG: That's what I admired about Foucault, WHO? It had an accomplished atmosphere. It reminded me of a period of time here in San Francisco back in the '80s when there was a serial killer loose in the Folsom [the gay leather community] and, at that time, I remember writing a draft for a horror film based upon the notion that cruising was the context by which the horror occurs. You've pursued that theme somewhat in Foucault, WHO? Could you talk about that film and its production? Where was it filmed?

Jed: It was filmed at The Loading Dock. [The Loading Dock was a popular denim and leather gay bar in San Francisco.]

MG: That's what I thought. I just wanted to be sure.

Jed: It's an interesting genesis and it was partly inspired by Andrew Cunanan the serial killer who was around in the '90s. There's a great quasi-autobiographical fiction work by Gary Indiana about Cunanan called Three Month Fever. I don't know if you're read that?

MG: I haven't; but, I like Indiana's work.

Jed: It's fantastic. That's possibly his best. So that was one of the inspirations. Foucault WHO? was made by me and my partner Wickie Stamps who's former editor of Drummer magazine and was very much a part of the leather scene.

MG: I was curious about your access to the leather bar. I don't associate transsexuals with the leather scene necessarily.

Jed: Yeah, although actually now there are a lot of international title-winning trans guys in the leather scene.

MG: Is that true?

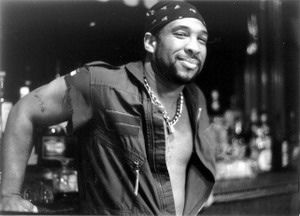

Jed: Yeah, there are some really hot tranny boys that have won titles like International Mr. Drummer, Mr. Leather, both in the "toppy" and "bottomy" categories. It's really important for some young trans men especially who identify as gay men. Wickie was very much of that world. She'd been a judge at International Mr. Drummer. With her name people never knew that she was a woman. They would write, "Dear Mr. Stamps" when they'd write in to Drummer magazine. That's actually kind of how I found out about her and decided I wanted to meet her in the first place. There's a woman who works in this hypermasculine magazine. If I were a woman, that's the kind of job I would have. I have to meet this person. I sort of scoped her out for years and then we got together. She knew all the players. Graylin Thornton, who plays the bartender in the film, is a prizewinning leather man who actually has worked as a bartender but he's also a filmmaker, a film guy, who lives in Southern California. He's an old buddy of Wickie's and he just volunteered to play that part. Thanks to him, we also made our entrée into The Loading Dock—which, then, was an exclusively male environment—easier; but, we also fit right in there. Wickie's very at home surrounded by leather men. I've never seen her more comfortable than in those environments. So that was that. The other important part of how—practically—it happened was that Wickie wrote a grant to Film Arts Foundation for first-time directors from under-represented communities and got the grant and they provided us with some funding, technical help and an amazing mentor, Margot Brier, who helped us for a year to plan for that film. We had no idea what we were doing. We had no money, nothing, and we were, like, "Okay, we're going to film it in Paris, and we're going to have cops breaking down the barricades, and we're going to have an S&M party with 800 people and I know I can do it because I have friends in Paris." The mentor and the teachers we had said, "Look, you are out of your minds. One location, five characters. Calm the hell down." [Laughs.]

Jed: Yeah, there are some really hot tranny boys that have won titles like International Mr. Drummer, Mr. Leather, both in the "toppy" and "bottomy" categories. It's really important for some young trans men especially who identify as gay men. Wickie was very much of that world. She'd been a judge at International Mr. Drummer. With her name people never knew that she was a woman. They would write, "Dear Mr. Stamps" when they'd write in to Drummer magazine. That's actually kind of how I found out about her and decided I wanted to meet her in the first place. There's a woman who works in this hypermasculine magazine. If I were a woman, that's the kind of job I would have. I have to meet this person. I sort of scoped her out for years and then we got together. She knew all the players. Graylin Thornton, who plays the bartender in the film, is a prizewinning leather man who actually has worked as a bartender but he's also a filmmaker, a film guy, who lives in Southern California. He's an old buddy of Wickie's and he just volunteered to play that part. Thanks to him, we also made our entrée into The Loading Dock—which, then, was an exclusively male environment—easier; but, we also fit right in there. Wickie's very at home surrounded by leather men. I've never seen her more comfortable than in those environments. So that was that. The other important part of how—practically—it happened was that Wickie wrote a grant to Film Arts Foundation for first-time directors from under-represented communities and got the grant and they provided us with some funding, technical help and an amazing mentor, Margot Brier, who helped us for a year to plan for that film. We had no idea what we were doing. We had no money, nothing, and we were, like, "Okay, we're going to film it in Paris, and we're going to have cops breaking down the barricades, and we're going to have an S&M party with 800 people and I know I can do it because I have friends in Paris." The mentor and the teachers we had said, "Look, you are out of your minds. One location, five characters. Calm the hell down." [Laughs.]MG: Well … and there's always the future, isn't there?

Jed: Yes! Next crime drama. Thematically, it was a strange mix of Wickie's background and mine. I come from a more middle class, studied postmodernism in college, Francophile kind of background and a huge Foucault fan. We were arguing about the script at one point and Wickie said, "I mean … Foucault WHO?" And that's how we got the title. There's this kind of tension between people that are just going to the bar and trying to get laid and people that see that as this context for all these amazing theories and things to talk about. That's represented in our relationship in some ways and in this film.

MG: I felt the film accurately captured the hazard—let's say at least among gay males—of the unbridled attraction to youth. Though the hazards of cruising in your film are depicted as life-threatening, I see them all-in-all as psyche-threatening period.

Jed: There's also the sexiness of cross-generational attraction. Wickie and I are very different generations and, for us, that's just sexy and interesting in itself. For me, a lot of how I wanted to set up the scenes in the movie, was to emphasize the slightly-twisted sexiness of the difference between the two men, how they looked, and how they were positioned, how one man is always in a higher position than the other, physically.

MG: First of all, I agree. One of the things that has attracted me most as a sexual creature in my adulthood was the erotic aspect of education and the grooming and sociality that comes from homosexual experience. As a younger man, I was attracted to older men because they taught me things and they provided things, experience….

Jed: What do you mean by "sociality"? That's a good word.

MG: When I arrived in San Francisco as a young man, I didn't know what a "gay" person was. Certainly, "queer" as an identification hadn't been developed yet. Older gay males taught younger gay males what being "gay" was and, at that time gayness—I have to state as an aside that I now think gayness is completely passé—but gayness, at that time, was an exciting and necessary social movement, it was a political statement that has been, of course, since then co-opted and turned into a consumerist lifestyle choice.

Jed: Yeah, I missed that. I missed that!

MG: Well, it was fun while it lasted. But you're involved in a powerful current momentum of transgender expression. I'm the old guard. You're the new energy.

Jed: It's interesting that you were talking about older gay men teaching younger men to be gay because I think there's a thing that … you can see very obviously that both of these movies are gay male movies.

MG: You think of DRIVE THRU as a gay male movie?!

Jed: Yes.

MG: I thought DRIVE THRU—which is your animated feature—was very edgy. Lightly, in four minutes, it puts the viewer into the driver's seat ….

MG: I thought DRIVE THRU—which is your animated feature—was very edgy. Lightly, in four minutes, it puts the viewer into the driver's seat ….Jed: Exactly. You understand.

MG: …to come into this situation of choices and most of them, to me, horrific choices.

Jed: Exactly!

MG: I'm never seen anything like this where such choices had to be made. For me, it one-upped gender parity issues because the film isn't about female/male gender parity; it's about female-to-male and male-to-female gender parity, which—in my admittedly limited experience of transgender issues—I've seen no one discuss or depict, so I have to commend you on exposing me to that disparity and for expressing the issue's cutting edge by way of film.

MG: I'm never seen anything like this where such choices had to be made. For me, it one-upped gender parity issues because the film isn't about female/male gender parity; it's about female-to-male and male-to-female gender parity, which—in my admittedly limited experience of transgender issues—I've seen no one discuss or depict, so I have to commend you on exposing me to that disparity and for expressing the issue's cutting edge by way of film.Jed: Thanks! All of those issues are important and there are definitely things that are easier about being FTM than MTF, although surgery is probably not one of them, but all those issues of parity are still important to me. First I want to say the thing about the gay maleness of it but I want to get back to what you were saying. It was interesting to me that you were talking about learning to be a gay man from older gay men because gay men are really important to me as a trans guy, as my sort of fellow queer male brothers. Butch women also but gay men also. Different people that express masculinity through a queer diffraction.

MG: Fellow performance artists.

Jed: Well, no, no, no. Not exactly. Gender as performativity is something I associate with more femme characteristics.

MG: Is that so? That's interesting.

Jed: Yeah. Masculinity is about the seeming lack of performance. Anyway, the thing is I've been hurt many many times by gay men, gay men in the Castro especially, gay men in the Castro Theater during the Queer Film Festival possibly most of all, who seem to feel no interest or obligation in learning that trans guys exist. I'm sort of an ambiguously gendered presentation person and so, for example, like guys at the theater will tell me I'm in line for the wrong bathroom, why don't I use the other bathroom, over and over and over. Gay men are the only people that … I mean it just hurts my feelings so much and it makes me so mad. The main thing I wanted from DRIVE THRU was for gay men to watch it actually and learn a tiny bit about our culture and that we exist and that there are men that are attracted to us and that we're your queer little brothers in a way and we're learning how to express maleness in a complex way and who better to learn it from than gay men? And I got to say butches too but there's a different … we're more likely to have had more access to butch women. It's kind of like what you were saying about learning to be a man from other men.

Jed: Yeah. Masculinity is about the seeming lack of performance. Anyway, the thing is I've been hurt many many times by gay men, gay men in the Castro especially, gay men in the Castro Theater during the Queer Film Festival possibly most of all, who seem to feel no interest or obligation in learning that trans guys exist. I'm sort of an ambiguously gendered presentation person and so, for example, like guys at the theater will tell me I'm in line for the wrong bathroom, why don't I use the other bathroom, over and over and over. Gay men are the only people that … I mean it just hurts my feelings so much and it makes me so mad. The main thing I wanted from DRIVE THRU was for gay men to watch it actually and learn a tiny bit about our culture and that we exist and that there are men that are attracted to us and that we're your queer little brothers in a way and we're learning how to express maleness in a complex way and who better to learn it from than gay men? And I got to say butches too but there's a different … we're more likely to have had more access to butch women. It's kind of like what you were saying about learning to be a man from other men.MG: Well, not to argue with you about it, but the performativity that I associate with masculine expression or, rather, masculine expressions (in the plural), the fact that it's not looked at as performance might be one of the things that hinders an appreciation of masculine expression as performance. As a gay male this has long been an issue for me. In the '70s when I first arrived in San Francisco I remember writing in my journal that the cruelest men I'd ever met were gay men. I had come from a straight rural culture where straight boys were my first sexual contacts and my first "boyfriends" and, amazingly, very nice to me. In retrospect that kind of surprises me actually. So when I arrived in San Francisco I was stunned by the throwaway attitudes in the sexual scene and it took me a while to understand that gay men had come to San Francisco from all parts of the States. Many of them had arrived bigoted, many of them had arrived racist, and many of them had arrived sexist.

Jed: And hurt and damaged also.

MG: It stunned me at that time to recognize the value of the diversity of that influx, however desirable or undesirable, and to factor in, as you say, the personal histories of hurt and damage. For example, could the particular beauty and specific power of the films of Marlon Riggs have been possible without the inherent racism in the Castro gay scene? Another issue as a gay male that has recently been concerning me in the realm of film is what I'm calling the queer colonialization of the medium. A film comes from Thailand, let's say, or Korea, or somewhere else, with a gender-variant theme and it's criticized and evaluated by American gay male aesthetics and not understood within its own cultural context. This is why I would argue performance is important because this is how individuals enact how they understand themselves, and it's often culturally inflected and distinguished. That's how I look at performativity. I don't think of it as something artificial.

Jed: Or whimsical.

MG: Whimsical or purely for entertainment value, as I often think of drag queens—not that I have anything against drag queens—but, when I'm talking about the performativity of gender as self-expression, I'm thinking of it as an honest enactment—not an acting out—of an authentic self-understood identity.

Jed: I like "enactment" as a word for it. I think that's great. It's somewhere between performance and self-expression but with more agency. Yeah, enactment. That's a good word.

MG: I'll be frank with you. When the transgender and transsexual voice first began to be heard, it confused me. I didn't understand it. It has taken me many years to understand it and, honestly, I'm only beginning to understand it. That's why I'm very honored to speak with you today because I consider you one its most articulate spokespeople.

Jed: That's very nice of you.

MG: I'm also intent on having it understood. That's why I was glad at Frameline's Persistent Vision Conference that they included the panel on up and coming voices and visions, which you moderated. Also, I've been keen on some of Ruby Rich's comments on the new filmmaking coming from the transgender sector. Do you align transgender with queer? Do you consider yourself a queer individual?

Jed: Definitely, yeah.

MG: So, for you, it's part of the same umbrella?

Jed: Were you there for the big throwdown about that at Ruby Rich's talk at Persistent Vision? Well, we tried to have a throwdown and she refused to have it. Ruby, I'm still ready to have that. I thought what she was saying about that was strange and bigoted and wrong.

MG: Could you define that? How did you understand what she said?

Jed: Well, she said queer is inclusive and transgender is exclusive and then a couple of us trannies questioned her about it and she said, "I don't have time. We're going to talk about other questions." It was strange. She's totally wrong. The development of "queer" as a term exactly parallels the history 10 or 20 years later of "transgender" as a term. You first had the term "gay" and then people fought for a bigger term that included all the kinds of queer self-expression.

MG: Would you consider it an anatomical bias?

Jed: Well, yeah, it started out that way. With gay and lesbian and so on it was mostly a sexist and an anti-bi or a bi-exclusive thing, like "gay" was used for everybody, but with "transgender" it used to be, "You're transsexual or you're a cross-dresser." And they even used that term initially in the FTM, the cross-dresser, even though there was only one person that anyone knew of who identified as a female-to-male cross-dresser. There was no word for anybody who didn't identify as 100% transsexual, gonna-have-all-the-surgeries-if-I-can-get-the-money-together, there wasn't a word for it, especially in the FTM world. In the MTF world there was transvestite, cross-dresser, there were a few nuances but still a lot of people left out of that. So "transgender" developed as the—it was the same thing as with "queer"—polemically, deliberately developed as an umbrella term to embrace more people and let the definitions be more fluid and more inclusive. That was fought for in my time in the last 10 years. As a trans person there were people that were of the camp to try to preserve "transsexual" as the distinct identity and if it's not all about the body to you, and all about changing your body, you're not part of us. We fought that and we won. The same damn thing as with "queer."

MG: So are you saying then—because I want to make sure my readers understand, let alone myself—are you saying that "transgender" is a more inclusive term than "transsexual"?

Jed: Absolutely.

MG: Okay. And that what Ruby was, perhaps, mistakenly holding onto was a transsexual definition?

Jed: No. I don't think she made a mistake. I think she's being very deliberate. I think we disagree. I learned a little more background about that later. I think that it's a personal … some kind of agenda particular to her that needs to be elucidated.

MG: Either way, it's a fascinating debate and this is how culture moves forward. I recorded her talk and the subsequent Q&A and I went back through all of that to try to understand what she was saying and what you were objecting to and the sense that I got was of these a priori assumptions that were tripping the dialogue up. In debates such as these you have to vigilantly monitor and track where the words being used in an argument are starting from and I suspect she was starting from a gay male perspective. That she was basically saying that gay males are not part of the transgender community. But when you are saying that gay males can be the elder brothers to help trans men achieve self-expression, you are including gay males in the transgender community.

Jed: Absolutely. The thing that we are all targeted on, some would argue, is gender variant self-expression or disobedience to our genders. You're disobeying your gender when you fall in love with a man. I'm disobeying my gender in everything I do every day. Some people would say that gender violation is what binds all queer people together and that queer people who identify as queer are a subset of transgender. That's one way to look at it. That's what I was trying to say to Ruby that day. I think that she feels personally hurt by something that is happening within the lesbian and FTM community. That's my theory, that she was speaking about herself….

MG: The tension between lesbians and FTM is a very controversial realm.

Jed: Well it is for some people but I didn't actually know that there were any of them left. [Laughs.] We're all dating each other now, you know what I mean? That's how Wickie and I resolved that. We hooked up at the butch FTM day of dialogue at the public library and we both went there looking to hook up. We were like "Dialogue, schmialogue, these people are HOT." The same way that a lot of racial issues are resolved within the gay male community. They're not resolved, but, they're dealt with in a more beautiful way than in some of the straight world, I think. Basically people are not so alone in their races in the gay male community, sometimes in this very beautiful way that I admire.

MG: Another platform that's developing for me now as an older gay male is conscious abstinence. I basically have given up sex because sex has always been nothing but problematic in my life even within my own communities, and at this point I've chosen to go abstinent, partly also because there are so many drugs involved in the sexual arena and that's problematic for me. I find now I'm in this other category, trying to be homo-affirmative or transgender-affirmative, without being sexual and there are people who don't understand what I'm doing at all. Do you understand?

Jed: [Laughs.] Well, yes. That's so sad and wrong. Because there's a lot of cool things about being queer; sex is just one of the benefits.

MG: To a certain extent, since I am an older gay male who has witnessed so many of these historical milestones within the gay culture here in San Francisco, suddenly now to have this ability to talk about queer film, transgender film, to talk with people, to publish it out there on the Internet, I'm feeling more queer than I ever have. More than when I was getting laid every weekend! In other words, it's not having sex with other men that has made me queer; it's changing the culture that has made me queer.

Jed: Yeah, yeah. That's the stuff that I love about being queer is the stuff that's like what we—because of this historical accident or whatever the hell—we can think about things in some different way. We can imagine transformations that other people don't as quickly imagine. That's the whole cool thing about it. What happened to that? Foucault was all about that and, as somebody said to me when this movie came out, most of the queers I'm talking to don't even know who Foucault is or how to pronounce his name, and somebody who's just six years older than me said to me, "Well, the requirements for being part of queer culture are really different than they were 20 years ago."

MG: Yes. Absolutely. That's where I would beg patience for older gay males who are now the establishment whose heads many young queers want chopped off. It was a hard enough battle for them as it was and it's sort of like coping with new technologies. The new lexicon has a learning curve as difficult as trying to program a new VCR. I won't even talk about cellulars and Blackberries!

Jed: I hope you know that I'm not talking about chopping people's heads off. My thing is I feel hurt that there are these queers who are sort of role models to me who don't know I exist and tell me I'm in the wrong place and, for some reason, it's the most painful thing for me about being trans. Honestly.

MG: I genuinely hope that's overcome in time. Shifting to movies….

Jed: Yay!!

MG: When Matt Florence interviewed you for Persistent Vision, I was pleasantly startled when you stated that The Talented Mr. Ripley was your favorite transgender film. I was so intrigued by that and would invite you—if at any time you want to publish any piece about transgender expression in film—please allow me to do so. I would never have thought of The Talented Mr. Ripley as an eloquent piece for transgender expression.

Jed: Well, I certainly don't think it was intended that way.

MG: No, no, but all queer reading is usually an imposed reading….

Jed: Right. At an angle to what was intended.

MG: Exactly. So I was curious about—along with The Talented Mr. Ripley—what other films you think express transgender experience because, clearly, you're not satisfied with the ones that are meant to express transgender experience.

Jed: Oh, God, yeah. [Laughs.] Although there are a couple of excellent actual transgender films that I love too. So you're talking about other films that express what it's like to be trans without being deliberately trans? I actually haven't thought about that.

MG: Because I think—in terms of reaching out to a non-transgender audience—that's one of the most effective ways to go about it.

Jed: Yeah, it might be cool to have a film festival where you pair—it's all double features, or all shorts and features—where you pair a trans short with a movie like The Talented Mr. Ripley. That could be cool. Or that could be a thing within Frameline or another queer film festival.

MG: Well, let's stay with The Talented Mr. Ripley then. What was it that you thought about that film that struck you as a trans man as something you could claim?

Jed: Well, yeah, because it's all about … I find that film beautiful and incredibly haunting.

MG: I went and bought it yesterday on dvd, in fact, based upon your comments.

Jed: Have you watched it?

MG: I've seen it before, but, I decided I wanted to watch it again and again and again with this queer reading.

Jed: I've watched it so many times. It's my favorite film. It's about envying something that somebody else has that you can't really have. It's the sensuality of that. The physical objects, the light in southern Italy, the beauty of this man's body and his life, and all the things that he has. It's such an eloquent representation of class. It's about class longing partly for Minghella the director for that story but it's so eloquent about how … I think money is this way anyway, money has this emotional sensory quality that we deny all the time, so it just loops in perfectly with this tangible yearning of being trans. I want my hands to be that shape. I want my thumb to be shaped like that man's thumb. I want to know what it feels like to have his genitals. I want to know what it feels like to have his incredibly un-self-aware entitled way of walking through the world, where he's just having fun and not worrying about all the shit I've had to worry about since I was born. Because, when you're raised as a girl, you learn by the time you're about six that girls are the second-class citizens of the world and you don't really matter. There's that part of it, which is just beautifully done in that movie. Minghella, the director, talking about that movie talks about his own class longing growing up as a poor son of Italians on the Isle of Wight and catering to rich, English guys, English people, all summer, the tourists.

Jed: I've watched it so many times. It's my favorite film. It's about envying something that somebody else has that you can't really have. It's the sensuality of that. The physical objects, the light in southern Italy, the beauty of this man's body and his life, and all the things that he has. It's such an eloquent representation of class. It's about class longing partly for Minghella the director for that story but it's so eloquent about how … I think money is this way anyway, money has this emotional sensory quality that we deny all the time, so it just loops in perfectly with this tangible yearning of being trans. I want my hands to be that shape. I want my thumb to be shaped like that man's thumb. I want to know what it feels like to have his genitals. I want to know what it feels like to have his incredibly un-self-aware entitled way of walking through the world, where he's just having fun and not worrying about all the shit I've had to worry about since I was born. Because, when you're raised as a girl, you learn by the time you're about six that girls are the second-class citizens of the world and you don't really matter. There's that part of it, which is just beautifully done in that movie. Minghella, the director, talking about that movie talks about his own class longing growing up as a poor son of Italians on the Isle of Wight and catering to rich, English guys, English people, all summer, the tourists.MG: What strikes me right off in that description—and I wrote a lot about this when I was younger—is that my identity came about through composite fashion. With each of my lovers, there was some physical quality—maybe it was their eyes, or their hair, or their biceps, or their legs, or their dick, one thing or another—that I claimed as mine. So that I ended up with this kind of ragdoll self-image.

Jed: But as a way to love all the parts of yourself?

MG: Absolutely. Because, at that point, I hadn't learned how to love myself yet.

Jed: You were practicing?

MG: Yes, I was practicing.

Jed: Yeah, that's so cool. You see what I mean, though? It's almost hard when you talk about it to find the difference between being a gay man and being a trans man in those ways. I totally relate to that. When I first came out as trans, I was in love with a man for a while and it was this thing of not even knowing what's the difference between wanting someone and wanting to be him? When you start relating to the physicality of the person that you desire and see it as similar to yours, is that queerness? What is that?

MG: John Cameron Mitchell did a good job of expressing that in Shortbus. He talks about permeability and impermeability as a liminal space of letting things in and keeping things out in terms of identity formation that is, frankly, brilliant.

Jed: That sounds brilliant. I'm not surprised. There's also in The Talented Mr. Ripley, if I become you, do I have to kill myself or do I have to kill you in order to supplant you? There's something about that in transness too. Some people speak about the person that they were dying and this new person replacing them.

MG: Do you think this might be the fear that some gay males have of trans men? That they fear being supplanted?

Jed: In what way?

MG: By a trans expression or a trans identity?

Jed: Some gay men, I imagine, are afraid that their attraction to a trans guy would make the gay man ungay, that if I'm attracted to somebody who doesn't have the same physical configuration I do, that erases my gayness.

MG: This is something I think a lot about because I have, in effect, given up "gay" and I have some difficulty relating to men who exclusively identify themselves as "gay" or those who pettily dismiss others as "gay." When people ask me, "Are you gay?", I say, "Oh no, no, no. I'm queer. Because, for me, gayness is a temporally-specific category. I don't think it applies anymore. I think it's a lazy term. Gayness was something that was a cultural fluorescence in the '70s and '80s, it's gone, and people who hold onto gayness too much are holding on to the commodification of gayness, they're consumers, and they're not questioning enough, and that's why I think they might be fearful of true questioning.

Jed: But I find that understandable too. You were talking about how for you it was so hard composing your identity and finding something to love about it in the first place that I can understand white-fistedly holding onto what you have managed to cobble together. I think it's very poignant.

MG: Did you see Transamerica? What did you think of it?

Jed: It had some infuriating flaws and things that I thought were done wrong and unnecessarily, but, I have to say it was a better-than-average trans movie. I'm not even rational on the subject, Michael. I could go on for hours about what I don't like about it, but it is better-than-average.

MG: At Persistent Vision there was much discussion about the inequality between lesbian visibility in cinema and gay male visibility in cinema, and I have to be honest and say that your shorts were the first time I even considered that FTM representation was totally out of whack with MTF representation. I would even say that, currently, MTF representation is somewhat chic. You're seeing more and more films about men who are performing feminine expression or women performing MTF characters but not as many performances in the other direction; the notable exception, of course, being Boys Don't Cry.

Jed: The thing is it follows sexism and queer culture in general so the way that—this is my shorthand for the whole thing—the way that gay men are hurt and targeted … the way that gay men are hurt by the culture is that they're targeted, beat up, singled out, they're super visible, hypervisible. John Cameron Mitchell talks about the need to hide as a universal queer thing but I disagree with that a little because the way that queer girls are targeted is … they're not targeted! They're invisible. They don't matter.

MG: They're ignored.

Jed: The same thing happens with MTFs. They're hypervisible and are targeted, beat up. FTMs don't exist, never heard of them. Literally there are trans women who have said to friends of mine with beards who are going on Geraldo together with the trans women, "What are you doing here, honey?" "I'm a trans man." "What's that?" So that's the overarching thing and that's sexist in itself. Someone—I don't know if it was Lauren Cameron—said, "What men do is always more interesting and important than what women do, even when the women are becoming men." [Laughs.]

MG: That's great. But I think it's fascinating, exactly what you've said, that the methodology by which trans people are kept down—that gay men are targeted and lesbians are not—is a strategy that enforces the hegemony of gender expression.

Jed: Yeah. It matters that gay men are sleeping with the wrong people. It's really important, even when you're six, it's important what the boys are doing, not so important what the girls are doing. If they're climbing trees and kissing girls, it's harmless because they're not important. They don't have dicks. They're not going to hurt anyone. It's harmless. And so tomboys are seen as somewhat charming, and often are! Tomboys, butches, FTMs are often—if they're not completely incapacitated by the damage they've been through—are often more charming than your average person. They've had to be because that's their way of maintaining that harmless, desexualized status and not being targeted.

MG: I find this fascinating. Questioning myself, in the last 5-6 years I've found myself more attracted to "bois", lesbians who are acting like softball jocks. I'm very attracted to them.

Jed: Who isn't?!! Anyone who isn't is crazy.

MG: But, again, it's been very challenging for me to deal with these feelings. I'm trying to understand them. To wrap things up, then—because I want to make sure I feed you your pancakes—is there anything you want to make sure gets said? Or have we covered all bases?

Jed: Trans film is getting better quickly because there is so much of it. I actually think that in some ways MTF trans people are under-represented now in the latest waves of trans film. I'm not sure why that is. MTFs do have a harder time with a lot of things in life than FTMs, economically for example.

MG: Is there a place to go to familiarize oneself with transgender cinema?

Jed: I wish there was, and there may be, and I may not know about it.

MG: If you find out, please alert me.

Jed: The trans film series at the queer film festivals. I can tell you a couple of my favorite films, which I would like to have you include if you have room. There's a movie called Shinjuku Boys, a Japanese documentary about, basically, the FTM spectrum of people in Japan that is the best literally trans movie that I've ever seen in my life. I felt ashamed to have my emotions so starkly exposed on the screen. I felt like I almost had to cover my face watching it. Different For Girls is a great British narrative trans film about trans woman played by Steven Mackintosh who's a great crime drama actor. It's just a very adorable great movie that's honest also. Then, Dell La Grace Volcano—who used to be the dyke photographer Della Grace—is a brilliant trans filmmaker who's made several films that are really great, some funny, some sexy, one of them Pansexual Public Porn is about trans guys having sex with gay guys literally in a park in London. It's a mix of documentary and fiction. Fantastic.

MG: That's good to know. I'll follow up and find out about those. Finally, what's up on the horizon for you? Are you working on any new piece? You've been traveling with DRIVE THRU?

Jed: DRIVE THRU is still making its way around the world. It's been at about 100 festivals. It showed in Japan this last month. I don't know if I gave you the Capybara? [Jed hands me a business card.] This is probably the next project.

MG: Okay. [Reading] Giant Rodents Taking Over the World. It's so cuuuuuuuuute!

Jed: That's the problem, Michael! 98% of people see the capybara as cute. I'm going to have to do something about that because I find him very very sinister.

MG: Do you? [Laughing.] But how can you? He's so cuuuuuuuuute!

Jed: This is a real issue.

MG: Well, you have time to work on it. My final spiel, my final schtick, is to advise you that—if you ever make a horror movie and you need someone to be killed off in the first scene—I will work for free.

Jed: Definitely!

MG: This is one of my fantasies. I don't know why. You get older and you think, "Why is this important to you? Getting a Ph.D. should be more important to you!" But actually the idea of being in a horror movie is more attractive because I've always loved the horror genre so much.

Jed: Right there with you.

MG: As I was growing up in the neighborhood and playing Monsters with the other kids, I was always the Monster. Then, later, when I took up acting, I was always the villain, so right now for me to be the helpless victim splattered to pieces in the first scene then out of the film has tremendous allure.

Jed: Yeah, actors are really into death scenes. That's great because Wickie and I definitely want to make horror movies.

MG: I would like to see you make one because Foucault, WHO? had a palpably sinister atmosphere. As I was watching it again this morning, I was thinking, "They all could be the serial killer! Is it the barback who's the murderer? Maybe even the bartender's the murderer? Maybe it's that guy who was in prison who's the murderer?"

Jed: Yeah, exactly. That's really good to know, Michael. I'm totally going to keep that in mind. I'll tell Wickie right away.

MG: Well, thank you very much. I appreciate you taking the time and now I'll feed you some pancakes.

Jed: All right!!

Foucault WHO? stills courtesy of Heads Will Roll Productions; © 2002 Calli Rose Lyons.