The thematic link between Marco Bellocchio's early piece I pugni in tasca / Fists In The Pocket (1965) and his recent Buongiorno, Notte / Good Morning, Night (2003) is palpably intriguing and great, insightful programming on the part of N.I.C.E. With a minimum sample of just three films, New Italian Cinema has succeeded in profiling Bellocchio's genius and piquing interest in the rest of his repertoire. As someone who was not familiar with Bellocchio's oeuvre, I'm grateful for the calculated exposure.

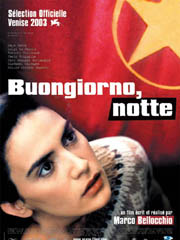

Good Morning, Night won Bellocchio the Little Golden Lion at the 2003 Venice Film Festival as well as an award for Outstanding Individual Contribution for a screenplay. As with Fists in the Pocket, much has been written about Good Morning, Night, so rather than reinvent the wheel, I will attempt more of a critical overview than any singular critique.

Pasquale Iannone's Senses of Cinema essay on Good Morning, Night sources the film's title to Emily Dickinson's poem "Good Morning Midnight."

Good morning midnight

I'm coming home

Day got tired of me

How could I of him?

Iannone notes that the story of the 1978 kidnapping and assassination of Italy's former Prime Minister Aldo Moro by the terrorist group Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades)—which, according to Sophie Arie of The Guardian is "still an open wound in Italian society"—had previously been committed to cinema by Giuseppe Ferrara in Il Caso Moro (1986) with Gian Maria Volonte as the ill-fated president of the DC (Christian Democrats). Roberto Herllitzka portrays Moro in Good Morning, Night. Salon's Andrew O'Hehir describes Herllitzka as the "spitting image" of the Prime Minister and praises his wonderful, "doleful" performance. As Iannone outlines, what differentiates Bellocchio's version is his eschewal of "Ferrara's solemn, quasi-documentary aesthetic for a highly subjective version of events, filtered through the consciousness of one of Moro's captors, 20-year-old Chiara (Maya Sansa) who, along with fellow brigadisti Mariano (Luigi Lo Cascio), Ernesto (Pier Giorgio Bellocchio) and Primo (Giovanni Calcagno), hold Moro hostage for 55 days in a Rome apartment."

Bellocchio describes his character Chiara as the piccola terrorista or "little terrorist", as if to diminuate terrorism will allow an intimate affection. What I especially like about Iannone's essay is how it captures one of the film's most brilliant scenes—certainly my favorite—where "Chiara reads a letter from Moro to his wife. A voiceover from Moro unveils the content of the letter. After a few sentences, it becomes clear that the voiceover is not in fact a reading of Moro's letter but a reading from a book that sits on Chiara's bedside table, a collection of letters from prisoners condemned to death during World War II. Bellocchio, in merging past and present through the subjectivity of Chiara, uses this sequence to delineate how the struggle against fascism and the sacrifices of the resistance during World War II have been forgotten. Organizations affiliated with the extreme-left are now committing the same atrocities as those of the extreme-right only three decades earlier. The director also intersperses images of Nazi atrocities to further strengthen the analogy." That this scene is scored with the anguished cries of Claire Torry from Pink Floyd's "The Great Gig in the Sky" insures a visceral response to Chiara's illumination ("His use of the music of Pink Floyd, in particular, must surely count as one of the most intelligent recent uses of popular music in film"). The hairs stood up on my neck in empathic recognition of the terrorists' misguided and tragic folly. Through the character of Chiara, Bellocchio "succeeds in giving a moral core to the film which cuts through the self-aggrandising rhetoric of the brigadisti."

As Acquarello states it at Strictly Film School: "By personalizing the inevitable tragedy from the point-of-view of Chiara, a deeply conflicted young woman whose surfacing humanity for the gentle-spoken, sensible, and conciliatory Moro—whom she sees as a father figure—and her resolute duty to the militant cause, Bellocchio creates a provocative, complex, and profoundly disturbing portrait of myopic ideology, self-righteousness, moral obligation, and the importance of communication and compromise."

"Chiara's personal conflict takes the movie beyond a dry, factual procedural," Armond White writes for The New York Press, "it becomes a wondrous and unsettling exploration of an ideologue's contradictions and misgivings." J. Hoberman, from The Village Voice, imagines Moro's period of captivity as a "rarefied spiritual struggle."

Reporting to Bright Lights Film Journal from the 2003 New York Film Festival, Megan Ratner details Bellocchio's claustrophobic mise en scène: "Bellocchio conveys the fear and suspicion of the cell members hiding out in an apartment purportedly inhabited by Chiara and her husband, who are as much prisoners as their hostage." Armond White, amplifies the description by stating the apartment "allows Bellocchio to pursue this political story as an intimate, domestic one. The close-quarters metaphor puts the tragedy into the home, creating an aura of perverse personal involvement and sinister accountability. It's a grave spinoff from Godard's La Chinoise about French Maoists practicing radicalism in a cell."

In her write-up for The Guardian, Sophie Arie positions the film's events "against the background of today's 'war on terror' " and implies that—within this context—"Moro's fate acquires a whole new significance." She continues, "The language of the terrorists who are willing to die for their cause is uncannily similar to that of today's Islamist terrorists. The enemy—the capitalist, imperialist, Christian establishment—is in many ways unchanged. In 1978 as in 2004, a small group of fervent idealists create an atmosphere of terror far larger than themselves."

Salon's Andrew O'Hehir admits that American unfamiliarity with Italian politics makes Good Morning, Night somewhat opaque and inaccessible, though not insurmountable. He describes the film as "an expressionist portrait, blending archival news footage with naturalistic but enigmatic scenes and fanciful dream sequences" unconstrained by the actual history of the Moro kidnapping since, indeed, "as Bellocchio has pointed out, the actual history of the event is none too clear." O'Hehir writes that "Bellocchio is performing an act of something like Jungian therapy on his nation, unpacking the most traumatic event of its recent history as a concatenation of dream symbols, and also as an allegorical way of addressing the tortured state the Western world, beset by terrorists both real and imaginary, finds itself in today." Though he finds the movie "strange and murky" and at times "frustrating", he also "found it profoundly moving in a way no regular thriller ever is." Armond White likewise capitulates that Bellocchio is uninterested in creating "suspense" and, instead, "takes advantage of already-determined history to look deeper."

Both O'Hehir and White highlight the "babysitting" scene. "In a funny-scary early scene," O'Hehir writes, "a neighbor dashes by to drop off her baby for a couple of minutes; Chiara looks at the little creature with mingled fear and disgust, but it's the sort of routine favor no young Italian woman is supposed to refuse. She stashes the baby on the sofa, handling him as if he were a ticking bomb—and then her compadres come lurching through the room, carrying the former prime minister in a packing crate." Armond White asserts this scene confirms the film's greatness. Chiara's "ruse of domesticity gets tested" when she "answers her doorbell and has a neighbor's baby shoved at her. Although she's some kind of outlaw (soon to be revealed as a member of a radical political sect with nefarious plans), that's providence that is placed in her arms. Bellocchio's superb visual jest teases the future of Italy and of political activism even as it arouses Chiara's filial compassion, the part of her humanity (and her untested maternity) that she had put aside for the cause. All that, in one image, is great filmmaking." J. Hoberman adds that this scene exemplifies the film's "understated magic realism."

White does a good job of comparing the backward glance of Bellocchio in Good Morning, Night with Bertolucci's backward glance in The Dreamers and praises Bellocchio's "extraordinary" attention to Chiara's dreams. "She has faded black-and-white visions of Russia's winter revolution (Lenin, Stalin). These include a remarkable documentary montage of actual political assassinations (ingeniously scored to The Dark Side of the Moon), reminding Chiara of the grim history she's about to join. Her only release from this political trap are these beautiful/horrifying dreams. Her male comrades play lethal real-life politics while she ponders the consequences. She secretly fantasizes conversing with Moro when the men sleep, as if making rapprochement with her father's underground legacy. The mix of news footage, dream and stylized drama is implicative and historical, amounting to a personally felt elegy. Good Morning, Night is full of simultaneous yearning and regret."

"Chiara's last dream," J. Hoberman writes, "is a near jaw-dropper—as though Bellocchio has imagined this cruel story through the wrong end of a telescope and staged it in a snow globe."

In her last dream Chiara configures an alternate outcome. Moro is seen escaping from captivity and walking free in morning light. In reality, Moro's bullet-ridden body was dumped on the Via Caetani, a quiet street in central Rome, midway between the Christian Democrat and Communist headquarters. The event was memorialized by a modest stone plaque embedded in the dark brick wall of a church.

Cross-published on Twitch.