Tuesday, March 25, 2008

CINEMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF THE ANIMA—Guy Maddin's The Heart of the World (2000)

Guy Maddin's The Heart of the World was prepared for the 25th anniversary of the Toronto International Film Festival, is only six minutes long, and purports to offer a founding myth on cinema itself. It was chosen by Vincent Canby of The New York Times as one of the 10 best films of the year 2000, surely a first for a film so short.

As Wikipedia summarizes the plot: Two brothers, mortician Nikolai and actor Osip (playing Christ in a Passion Play), love the same woman—scientist Anna, who studies the earth's core, or the "heart of the world." Anna discovers that the world is in danger. In order to save it, she must choose between the brothers, and finally decides on a rich industrialist, Akmatov. As a result, the very heart of the world has a heart attack. Realizing what she has done, she strangles Akmatov and enters the earth's core, replacing the failed heart with her own. The world is then saved by the new message, Kino.

Kino, of course, is Russian for "cinema" and is, likewise, the root of the word "kinetic", an adjective completely appropriate to Maddin's "founding myth on cinema." Maddin deliberately references and parodies soviet montage cinema of the 1920s, German Expressionism of the 1920s, and silent melodrama film. He cites Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) and La Fin du monde (1931), which likewise employs an end-of-world scenario with tension between two brothers (a scientist and a Christ figure). Mark Peranson describes Maddin's short as a "Soviet-constructivist-cum-sci-fi head rush … shot out of an Uzi of inspiration." His City Pages cohort Rob Nelson describes it as a "six-minute music-video-cum-Eisensteinian-sci-fi-workout." Hyphenated descriptions abound to situate Maddin's mash-up of styles and techniques.

Beebe—cognizant of the "workout"—reminds us that he specifically chose to screen The Heart of the World because it privileges image over narrative. He encourages us to let the images of the film wash over us and stresses that watching movies is good training in "image sense."

State scientist Anna (Leslie Bais) is the anima of Maddin's The Heart of the World. Anima is, indeed, the archetype at the heart of filmmaking itself. Proposing that we watch the film three times to sift out and strengthen reactions (or as one IMdb user wrly phrased it: "watch, rinse, repeat"), Beebe asks us after the first screening for an adjective to describe our reactions. Several come up—agitated, melodramatic, frenetic, exaggerated, paniced, pressured, frantic, intense, visceral—all of which, Beebe offers, would be adequate to describe the anima. The film colonizes the body with somatized sensations, underscoring that the anima is a maddening urgency from within. Freudians don't much like the anima; for them it's the infantile psyche, hysterical. Many men would rather develop a strong persona than develop their anima. Rather than carefully dismantling defenses, they would rather shore up the persona.

I mention that one of the images that most struck me was the silent film convention of the aperture, the iris, as a means of access to the film's events. Beebe quotes Wim Wenders' comment that "film is seeing" and appends that the anima is seeing film with the anima eye. Whose eye is looking out from the screen? Is it Anna's as she looks into the machine that allows her to see the disconcerting and cephalopodic heart of the world? He thinks so.

Anna, however, is not an anima personal to Guy Maddin but more what James Hillman has described as the anima mundi: the soul of the world or culture's soul. Looking at her as she announces her dire predictions ("triple-checked") channeled through Soviet agitprop conventions, she exemplies what happens when one is caught in the grip of the anima; a kind of propagandistic impulse; a propaganda suffused with idealism; an idealistic urgency to save the world. There is this redemptive quality to the anima and, Beebe wonders if we identify with the anima when we wish redemption?

Beebe reiterates that The Heart of the World is a founding myth about how movies are made. It's heraldic, announcing the triumph of a new world order through cinema. And it details the historicity of the process by which cinema achieves integrity. Anima is implicated in the development of integrity. At the beginning of the film Anna is in love with two brothers: Nikolai (Shaun Balbar), the mortician-engineer, and Osip (Caelum Vatnsdal), the actor playing Jesus who is likewise suffering a Messianic complex. Both brothers are stricken by Anna's beauty and battle for her attention. When Anna pronounces the grim fate of the world, they compete for a solution.

Beebe suggests Nikolai, the mortician, represents cinema's initial murderous gaze, the original impulse to document and record through film, freezing (killing) things in time, nailing bodies in coffins (commensurate to finishing films up and putting them "in the can"). Osip, in his guise as Jesus, adopts the opposite position, representing a cinema that is a spiritual experience where bodies are resurrected and freed from their coffins. As an aside, Beebe admits to becoming "hot" at horatory cinema meant to exhort; cinema's popular usage to push spiritual agendas. Clearly, both approaches are fraught with peril and neither—in Maddin's film—serve to save the heart of the world. One rages forward with cold-hearted progress; the other performs miracles through reverse footage. One of my favorite images is the horror on Nikolai's face when he witnesses Osip's resurrected corpses. In a way, their opposing approaches negate each other.

Then along comes the dark horse contender, a lustful industrialist named Akmatov (Greg Klymkiw), who seduces and sways Anna with his chest of gold coins. She swoons and is taken by him on their honeymoon. One IMdb user describes Akmatov as a "plutocrat", which—though it was not discussed at the seminar—is an intriguing mythic reference for me, in the sense that "Pluto" (aka Hades), is a Lord of Abduction (as in the Persephone myth) who as King of the Underworld has access to the mineral wealth—veins of gold and sparkling gemstones—beneath the surface of the earth. Though Dr. Beebe claims it's gold coins that are being shoveled into Akmatov's phallic cannon, I'm not convinced and can't quite tell from the film itself; they look more to me like diamonds and chunks of coal, in turn. Either way, gold or diamonds, they suggest underworld wealth. If the marriage of Hades and Persephone is, indeed, a configuration of a woman's marriage initiation, is it any wonder that a diamond ring set in gold is used to seal the contract?

Why would Anna choose the aggressive Industrialist? Does she really choose, or does she simply succumb? In the face of an assertive will, Beebe suggests, the anima can retreat into a vegetative state, much like the story of Apollo's pursuit of Daphne and her winsome smile over the shoulder as she transforms into an inaccessible laurel tree.

Unfortunately, by choosing Akmatov, the world suffers a seismic heart attack. This heartquake (earthquake?) jolts Anna back into conscious action, reminding her that her true mission is to save the world. She strangles Akmatov and sacrifices herself to become the world's heart transplant. By this act the world is reborn as cinema and is shown projected onto the hearts of the world's inhabitants.

There's a lot to tease out here. First, as a style of cinema—in contrast to Nikolai's documentary approach and Osip's horatory approach—Akmatov represents commercial cinema, Hollywood as we know it today, where the bottom line rules even as expensive movies are made about how bad money is. One could say that—because the movie industry is anima-driven—it is money-crazy. And therein lies the anima's dilemma. Just as Luis Buñuel vociferously detested Nicholas Ray's dinner party assertion that each movie he makes must cost more than the one he's just finished in order to remain a successful filmmaker, the temptation of financing must either be resisted or finagled in order for the integrity of creative vision to exist. Film is for the realization of an integrity of vision. This aligns with James Hillman's thesis in Thought of the Heart and Soul of the World, wherein the "thought of the heart" is understood as the capacity to imagine truly. In The Heart of the World, Maddin pleads a case for visionary filmmaking; his kind of filmmaking.

Anna has to kill her strange bedfellow the Industrialist in order to overcome her sellout and to return to her mission. Anna becomes an imagemaking faculty. She becomes a radiant star. When the anima is integrated, it becomes a function, hopefully a broadened transcendent function. This references the idea that the anima is also fate; that the anima is trying to live out her own fate. Anima integration is more believable in those who can be vulnerable. Anima starts out as an almost ridiculously-hyped subjectivity. If the anima is integrated, a balanced subjectivity becomes possible.

Dr. Beebe is fond of using Jungian typology to understand the characters in films, if not the filmmakers themselves. Basically, C.G. Jung proposed that individuals fall into primary types of psychological function. He said there were four main functions of consciousness. Two are perceiving functions (sensation and intuition) and two are judging functions (thinking and feeling). The functions are modified by two main attitude types: introversion and extroversion. Jung theorized that whichever function dominated consciousness, its opposite function is repressed and characterizes unconscious behavior. This compensatory model generates eight psychological types as follows: (1) Extraverted Sensation; (2) Introverted Sensation; (3) Extraverted Intuition; (4) Introverted Intuition; (5) Extraverted Thinking; (6) Introverted Thinking; (7) Extraverted Feeling; and (8) Introverted Feeling. It's upon these eight psychological types that personality questionnaires such as the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) have been developed.

Anima, Dr. Beebe argues, is tied up with the psyche's inferior function. An introverted feeling type thinks in images and he describes Anna as an extroverted thinking anima. I will confess straight off that I have a longstanding resistance to the formulaic structures of Jungian typology. It's not that I don't believe these psychic combinations are in effect; but, I find it very difficult to talk about them without it all turning into alphabet soup or a game of Scrabble on a shaking train. Along with such prognosticative systems as astrology and the I Ching, what I can appreciate about discussions of typology are the association of ideas they generate; but, other than for that, for me it all devolves into a big guessing game and, frequently, unnecessary argument. Like poetry, typology is approximate and inferential and, I confess, is my least favorite aspect of Dr. Beebe's methodology in discussing film. This will surely be something I explore with him when I interview him for The Evening Class.

Monday, March 24, 2008

CINEMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF THE ANIMA—The Nine Qualities of the Anima In Film

When I first announced that San Francisco's C.G. Jung Institute was offering a one-day seminar with Dr. John Beebe on Cinematic Expressions of the Anima: A Day With the Feminine in Film, I replicated the program brochure. In gist, Dr. Beebe selected Guy Maddin's Heart of the World and Jean Vigo's L'Atalante to be shown together. "Both are recognized film classics possessed of abundant charm, humor, poignancy, and vitality and cherished by connoisseurs; yet since their first release neither has reached a mainstream audience. This is because they challenge conventions of narrative cinema to make room for an expression of the unconscious. They privilege the image over narrative, and they complicate the masculine hero myth with another archetypal pattern, the realization and revaluation of the feminine. Both have strikingly original soundtracks, and both draw anachronistically on silent film techniques. Both are unusually short for the archetypal ground they cover."

When I first announced that San Francisco's C.G. Jung Institute was offering a one-day seminar with Dr. John Beebe on Cinematic Expressions of the Anima: A Day With the Feminine in Film, I replicated the program brochure. In gist, Dr. Beebe selected Guy Maddin's Heart of the World and Jean Vigo's L'Atalante to be shown together. "Both are recognized film classics possessed of abundant charm, humor, poignancy, and vitality and cherished by connoisseurs; yet since their first release neither has reached a mainstream audience. This is because they challenge conventions of narrative cinema to make room for an expression of the unconscious. They privilege the image over narrative, and they complicate the masculine hero myth with another archetypal pattern, the realization and revaluation of the feminine. Both have strikingly original soundtracks, and both draw anachronistically on silent film techniques. Both are unusually short for the archetypal ground they cover."Dr. Beebe's approach—after showing each film in full—was to "lead the participants in a discussion of the psychological implications of its imagery, demonstrating what it has to tell us about the role of the feminine in ensouling and centering the self, and about masculine attitudes that block and enable the psyche's ability to manifest wholeness." I offer up my notes on the seminar with the caveat that my understanding of Jungian psychology is still on a learning curve after all these years and—should any of these ideas provoke interest—I strongly suggest my readers follow through with Dr. Beebe's upcoming volume The Presence of the Feminine in Film, co-authored by Virginia Apperson and soon to be released by Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung often said that work on confronting one's "shadow self" was the "apprentice piece"; whereas, confronting one's "anima" was the masterpiece. Shadow and anima are two of the main archetypes within Jung's theory of the collective unconscious. Both are psychological functions that generate projection. In the case of the shadow, an individual projects his own darkness upon others, which is a fairly straightforward concept; but, the role of the anima in individuation is in some ways tantalizingly more complex and not as easy to pin down. In general psychological parlance it is the inner personality that is turned towards the unconscious of the individual (contrasted with the "persona", which is the social façade) and—within its most popular understanding—retains a contrasexual element (i.e., it is a feminine principle especially present in men, much like the "animus" is a masculine principle present in women) that organizes the structures of the unconscious. I qualify that last statement because recent Jungian scholasticism has questioned the exactitude of the contrasexual equation. In his own practice, Dr. John Beebe has observed that the "anima" is not reserved just for men nor the "animus" for women; but, as averages go, he sees it as a 3:1 ratio.

Detailing how he came to use film as a fulcrum to teach Jungian theory, Dr. Beebe recounted his involvement with the Ghost Ranch seminars organized by Murray Stein and situated at the former ranch of artist Georgia O'Keefe. This was the first time that Beebe showed a film to a professional audience and it just so happened to be Jean Vigo's L'Atalante. But as the purpose of the Ghost Ranch seminars was to generate papers for publication so that Jungian theory could take academic shape, Beebe was forced to write up his presentation and, thus, his first essay on film. That paper "The Anima In Film" is available online in its entirety and is a great introductory read to the Jungian methodology Beebe developed to finesse film. As cinema is a projective medium, the anima's involvement seems obvious; but, even Dr. Beebe has tweaked the title of his first film essay, as well as his upcoming book, to designate that it's really not so much about the anima "in" film as it is about the anima "through" film. The director who creates a film is comparable to the self that creates a dream.

To introduce the thrust of his seminar, Dr. Beebe provided the nine qualities he has come to associate with the anima's presence in film. I quote from his essay:

1. Unusual radiance (e.g., Garbo, Monroe). Often the most amusing and gripping aspect of a movie is to watch ordinary actors or actresses (e.g., Melvyn Douglas and Ina Claire in Ninotchka) contend with a more mind-blowing presence—a star personality who seems to draw life from a source beyond the mundane (e.g., Garbo in the same film). This inner radiance is one sign of the anima—and it is why actresses asked to portray the anima so often are spoken of as stars and are chosen more for their uncanny presence, whether or not they are particularly good at naturalistic characterization.

1. Unusual radiance (e.g., Garbo, Monroe). Often the most amusing and gripping aspect of a movie is to watch ordinary actors or actresses (e.g., Melvyn Douglas and Ina Claire in Ninotchka) contend with a more mind-blowing presence—a star personality who seems to draw life from a source beyond the mundane (e.g., Garbo in the same film). This inner radiance is one sign of the anima—and it is why actresses asked to portray the anima so often are spoken of as stars and are chosen more for their uncanny presence, whether or not they are particularly good at naturalistic characterization. 2. A desire to make emotional connection as the main concern of the character. One of the ways to distinguish an actual woman is her need to be able to say "no," as part of the assertion of her own identity and being. (Part of the comedy of Katharine Hepburn is that she can usually only say no; so that when she finally says "yes," we know it stands as an affirmation of an independent woman's actual being.) By contrast, the anima figure wants to be loved, or occasionally to be hated, in either case living for connection, as is consistent with her general role as representative of the status of the man's unconscious eros and particularly his relationship to himself. (Ingrid Bergman, in Notorious, keeps asking Cary Grant, verbally and nonverbally, whether he loves her. We feel her hunger for connection and anticipate that she will come alive only if he says yes. His affect is frozen by cynicism and can only be redeemed by his acceptance of her need for connection.) [Dr. Beebe credited fellow Jungian analyst Beverly Zabriskie for this insight. She reacted to a screening of Gaslight where Beebe described Ingrid Bergman's character Paula Alquist Anton as a woman who comes alive when Charles Boyer's character Gregory Anton says yes to her love. Actually, Zabriskie countered, she's not a real woman. An actual woman would say "no" more than Paula does in order to define herself. That's when Beebe realized that the anima is not an actual woman.]

2. A desire to make emotional connection as the main concern of the character. One of the ways to distinguish an actual woman is her need to be able to say "no," as part of the assertion of her own identity and being. (Part of the comedy of Katharine Hepburn is that she can usually only say no; so that when she finally says "yes," we know it stands as an affirmation of an independent woman's actual being.) By contrast, the anima figure wants to be loved, or occasionally to be hated, in either case living for connection, as is consistent with her general role as representative of the status of the man's unconscious eros and particularly his relationship to himself. (Ingrid Bergman, in Notorious, keeps asking Cary Grant, verbally and nonverbally, whether he loves her. We feel her hunger for connection and anticipate that she will come alive only if he says yes. His affect is frozen by cynicism and can only be redeemed by his acceptance of her need for connection.) [Dr. Beebe credited fellow Jungian analyst Beverly Zabriskie for this insight. She reacted to a screening of Gaslight where Beebe described Ingrid Bergman's character Paula Alquist Anton as a woman who comes alive when Charles Boyer's character Gregory Anton says yes to her love. Actually, Zabriskie countered, she's not a real woman. An actual woman would say "no" more than Paula does in order to define herself. That's when Beebe realized that the anima is not an actual woman.]3. Having come from some, quite other, place into the midst of a reality more familiar to us than the character's own place of origin. (Audrey Hepburn, in Roman Holiday, is a princess visiting Rome who decides to escape briefly into the life a commoner might be able to enjoy on a first trip to that city.)

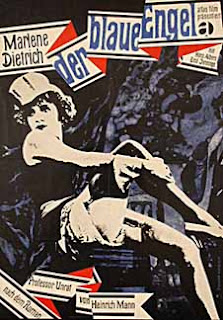

4. The character is the feminine mirror of traits we have already witnessed in the attitude or behavior of another, usually male, character. (Marlene Dietrich as a seductive carbaret singer performing before her audience in The Blue Angel displays the cold authoritarianism of the gymnasium professor of English, Emil Jannings, who manipulates the students' fear of him in the opening scene of the movie. Jannings pacing back and forth in front of his class and resting against his desk as he holds forth are mirrored in Dietrich's controlling stride and aggressive seated posture in front of her audience.) [This quality leans into the contrasexual understanding of the anima, which configures her as a contrasexual mirror. Beebe, in fact, once overheard one man explaining to the other, "Your anima is the woman you are." Dietrich's deployment of the archetype is furthered by her purposeful masculine attire, as if to draw the comparison tighter.]

4. The character is the feminine mirror of traits we have already witnessed in the attitude or behavior of another, usually male, character. (Marlene Dietrich as a seductive carbaret singer performing before her audience in The Blue Angel displays the cold authoritarianism of the gymnasium professor of English, Emil Jannings, who manipulates the students' fear of him in the opening scene of the movie. Jannings pacing back and forth in front of his class and resting against his desk as he holds forth are mirrored in Dietrich's controlling stride and aggressive seated posture in front of her audience.) [This quality leans into the contrasexual understanding of the anima, which configures her as a contrasexual mirror. Beebe, in fact, once overheard one man explaining to the other, "Your anima is the woman you are." Dietrich's deployment of the archetype is furthered by her purposeful masculine attire, as if to draw the comparison tighter.]5. The character has some unusual capacity for life, in vivid contrast to other characters in the film. (The one young woman in the office of stony bureaucrats in Ikiru is able to laugh at almost anything. When she meets her boss, Watanabe, just at the point that he has learned that he has advanced stomach cancer and is uninterested in eating anything, she has an unusual appetite for food and greedily devours all that he buys her.)

6. The character offers a piece of advice, frequently couched in the form of an almost unacceptable rebuke, which has the effect of changing another character's relation to a personal reality. (The young woman in Ikiru scorns Watanabe's depressed confession that he has wasted his life living for his son. Shortly after, still in her presence, Watanabe is suddenly enlightened to his life task, which will be to use the rest of his life living for children, this time by expediting the building of a playground that his own office, along with the other agencies of the city bureaucracy, has been stalling indefinitely with red tape. He finds his destiny and fulfillment in his own nature as a man who is meant to dedicate his life to the happiness of others, exactly within the pattern he established after his wife's death years before, of living for his son's development rather than to further himself. The anima figure rescues his authentic relationship to himself, which requires a tragic acceptance of this pattern as his individuation and his path to self-transcendence.) [Many years ago at an earlier seminar of Dr. Beebe's, I befriended Francis Lu, a therapist who had written an incisive article on Kurosawa's Ikiru and mailed it to me. Francis has since gone on to teach film at many Esalen retreats. It was many years before I finally saw Ikiru (which, appropriately, means "to live"), but I remembered his comments and Dr. Beebe concurs that it is one of the best treatments of the film. Another example of this quality would be The Consolation of Philosophy, written by Boethius while he was imprisoned awaiting execution. In that piece the anima arrives as Lady Philosophy. She consoles Boethius by discussing some rather unpleasant things that significantly alter his perception of the world.]

6. The character offers a piece of advice, frequently couched in the form of an almost unacceptable rebuke, which has the effect of changing another character's relation to a personal reality. (The young woman in Ikiru scorns Watanabe's depressed confession that he has wasted his life living for his son. Shortly after, still in her presence, Watanabe is suddenly enlightened to his life task, which will be to use the rest of his life living for children, this time by expediting the building of a playground that his own office, along with the other agencies of the city bureaucracy, has been stalling indefinitely with red tape. He finds his destiny and fulfillment in his own nature as a man who is meant to dedicate his life to the happiness of others, exactly within the pattern he established after his wife's death years before, of living for his son's development rather than to further himself. The anima figure rescues his authentic relationship to himself, which requires a tragic acceptance of this pattern as his individuation and his path to self-transcendence.) [Many years ago at an earlier seminar of Dr. Beebe's, I befriended Francis Lu, a therapist who had written an incisive article on Kurosawa's Ikiru and mailed it to me. Francis has since gone on to teach film at many Esalen retreats. It was many years before I finally saw Ikiru (which, appropriately, means "to live"), but I remembered his comments and Dr. Beebe concurs that it is one of the best treatments of the film. Another example of this quality would be The Consolation of Philosophy, written by Boethius while he was imprisoned awaiting execution. In that piece the anima arrives as Lady Philosophy. She consoles Boethius by discussing some rather unpleasant things that significantly alter his perception of the world.]7. The character exerts a protective and often therapeutic effect on someone else. (The young widow in Tender Mercies helps Robert Duvall overcome the alcoholism that has threatened his career.)

8. Less positively, the character leads another character to recognize a problem in personality which is insoluble. (In Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place, the antisocial screenwriter played by Humphrey Bogart meets an anima figure played—with a face to match the cool mask of his own—by Gloria Grahame, who cannot overcome her mounting doubts about him enough to accept him as a husband. Her failure to overcome her ambivalence is a precise indicator of the extent of the damage that exists in his relationship to himself.) [Beebe extolled Grahame as an actress who has not been fully given her due for expressing wit against patriarchy, as she likewise does in Fritz Lang's The Big Heat. Such wit mirrors the shadow of patriarchy. As someone who suffered in legal support for many years, I frequently commiserated with playwright Mike Black about how—if it weren't for the wisecracking examples of Eve Arden and Thelma Ritter—I would never have survived as a legal secretary. Lawyer's egoes were my training ground. Mike became inspired by this admission and wrote me a play called The Norma Desmond Strategem which accentuated this wisecracking strategy of survival, and which I performed at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. It was, needless to say, cathartic.]

8. Less positively, the character leads another character to recognize a problem in personality which is insoluble. (In Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place, the antisocial screenwriter played by Humphrey Bogart meets an anima figure played—with a face to match the cool mask of his own—by Gloria Grahame, who cannot overcome her mounting doubts about him enough to accept him as a husband. Her failure to overcome her ambivalence is a precise indicator of the extent of the damage that exists in his relationship to himself.) [Beebe extolled Grahame as an actress who has not been fully given her due for expressing wit against patriarchy, as she likewise does in Fritz Lang's The Big Heat. Such wit mirrors the shadow of patriarchy. As someone who suffered in legal support for many years, I frequently commiserated with playwright Mike Black about how—if it weren't for the wisecracking examples of Eve Arden and Thelma Ritter—I would never have survived as a legal secretary. Lawyer's egoes were my training ground. Mike became inspired by this admission and wrote me a play called The Norma Desmond Strategem which accentuated this wisecracking strategy of survival, and which I performed at the San Francisco Fringe Festival. It was, needless to say, cathartic.] 9. The loss of this character is associated with the loss of purposeful aliveness itself. (The premise of L'Avventura is the disappearance of Anna, who has been accompanied to an island by her lover, a middle-aged architect with whom she has been having an unhappy affair. We never get to know Anna well enough to understand the basis of her unhappiness, because she disappears so early in the film, but we soon discover that the man who is left behind is in a state of archetypal ennui, a moral collapse characterized by an aimlessly cruel sexual pursuit of one of Anna's friends and a spoiling envy of the creativity of a younger man who can still take pleasure in making a drawing of an Italian building.) [In L'Avventura especially, Beebe added, you can witness the process of a "puer" becoming a "senex" without having incorporated his anima, as a process of petrification. He offered as an alternate example the story of Vertigo, which he explores more thoroughly in the above-referenced article.]

9. The loss of this character is associated with the loss of purposeful aliveness itself. (The premise of L'Avventura is the disappearance of Anna, who has been accompanied to an island by her lover, a middle-aged architect with whom she has been having an unhappy affair. We never get to know Anna well enough to understand the basis of her unhappiness, because she disappears so early in the film, but we soon discover that the man who is left behind is in a state of archetypal ennui, a moral collapse characterized by an aimlessly cruel sexual pursuit of one of Anna's friends and a spoiling envy of the creativity of a younger man who can still take pleasure in making a drawing of an Italian building.) [In L'Avventura especially, Beebe added, you can witness the process of a "puer" becoming a "senex" without having incorporated his anima, as a process of petrification. He offered as an alternate example the story of Vertigo, which he explores more thoroughly in the above-referenced article.]

EIJI TSUBURAYA—Battle In Outer Space (Uchū Daisen'sō, 1959) and Mothra (Mosura, 1961)

Though styles apart, along with his American counterpart Ray Harryhausen, Japanese tokusatsu (special effects) wizard Eiji Tsuburaya left an indelible imprint on my childhood sensibility. Balanced with the coming-to-life of the bronze Talos statue in Harryhausen's Jason and the Argonauts are the images of Godzilla ravaging Tokyo. No wonder I was always begging my mom to let me go to the movies! Imagine my delight that—in conjunction with the Chronicle Books publication of San Franciscan author August Ragone's impassioned visual biography Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters—Landmark Cinemas and San Francisco's Clay Theatre hosted a Tsuburaya double-bill of Battle In Outer Space and Mothra in dazzling Tohoscope, with Ragone in attendance to introduce the films and sign his book. My thanks to Bruce Fletcher of Dead Channels for alerting me to same. Anticipate an interview with August Ragone in the next week or so.

Though styles apart, along with his American counterpart Ray Harryhausen, Japanese tokusatsu (special effects) wizard Eiji Tsuburaya left an indelible imprint on my childhood sensibility. Balanced with the coming-to-life of the bronze Talos statue in Harryhausen's Jason and the Argonauts are the images of Godzilla ravaging Tokyo. No wonder I was always begging my mom to let me go to the movies! Imagine my delight that—in conjunction with the Chronicle Books publication of San Franciscan author August Ragone's impassioned visual biography Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters—Landmark Cinemas and San Francisco's Clay Theatre hosted a Tsuburaya double-bill of Battle In Outer Space and Mothra in dazzling Tohoscope, with Ragone in attendance to introduce the films and sign his book. My thanks to Bruce Fletcher of Dead Channels for alerting me to same. Anticipate an interview with August Ragone in the next week or so.I would be hardpressed to outdo Ragone's own synopses of the films at his site The Good, the Bad, and Godzilla, where he has written up both Battle In Outer Space and Mothra. But I would like to share some of my notes from Ragone's slide-illustrated introduction to both films, which supplement his blog entries.

Yoshio Tsuchiya, who plays Iwamura—the character who becomes possessed by the aliens—spent a lot of his career either in Akira Kurosawa's films or playing possessed madmen or monsters in these science fiction films. At that time at Toho Studios, their ensemble of actors were under contract to perform in whatever projects Toho was producing, whether Kurosawa's arthouse films or these science fiction genre films. Ragone made a keen point of noting critical prejudices at the time against genre films. One of the critics who complained that none of the actors in Godzilla could act—a film in which Takashi Shimura played paleontologist Dr. Kyouhei Yamane—overlooked that when Shimura played the war-weary samurai Kambei Shimada in Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai, this selfsame critic proclaimed him as "one of the most important actors in the world."

Yoshio Tsuchiya, who plays Iwamura—the character who becomes possessed by the aliens—spent a lot of his career either in Akira Kurosawa's films or playing possessed madmen or monsters in these science fiction films. At that time at Toho Studios, their ensemble of actors were under contract to perform in whatever projects Toho was producing, whether Kurosawa's arthouse films or these science fiction genre films. Ragone made a keen point of noting critical prejudices at the time against genre films. One of the critics who complained that none of the actors in Godzilla could act—a film in which Takashi Shimura played paleontologist Dr. Kyouhei Yamane—overlooked that when Shimura played the war-weary samurai Kambei Shimada in Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai, this selfsame critic proclaimed him as "one of the most important actors in the world." Ragone offered slides of the original concept designs for the aliens in Battle In Outer Space, which proved to look quite different from what production costs finally allowed. He highlighted Shigeru Komatsuzaki's concept designs for the space aircraft. His slideshow included several production stills of Tsuburaya on the set of Battle In Outer Space (which I note are not included in the book) and detailed how some of the effects scenes were accomplished, especially during the final battle on Earth when the aliens invade with their anti-gravity beam. Tsuburaya and his technicians filmed in an area below a suspension bridge with wires on wheels, which allowed them to pull up the miniatures and to shoot their ascension in natural light. The miniatures were made of brittle wafer-thin paraffin, which—along with being blown around by big fans—could easily be lifted by wires. The scene was shot with two cameras. Tsuburaya frequently employed multiple cameras—a technique often ascribed as Akira Kurosawa's signature brilliance—but, Tsuburaya filmed this way as well. After nearly 50 years, this effects scene still proves thrillingly impressive on the big screen in color in Tohoscope. A whole layer of comedy was added by the film being shown in its dubbed version.

Ragone offered slides of the original concept designs for the aliens in Battle In Outer Space, which proved to look quite different from what production costs finally allowed. He highlighted Shigeru Komatsuzaki's concept designs for the space aircraft. His slideshow included several production stills of Tsuburaya on the set of Battle In Outer Space (which I note are not included in the book) and detailed how some of the effects scenes were accomplished, especially during the final battle on Earth when the aliens invade with their anti-gravity beam. Tsuburaya and his technicians filmed in an area below a suspension bridge with wires on wheels, which allowed them to pull up the miniatures and to shoot their ascension in natural light. The miniatures were made of brittle wafer-thin paraffin, which—along with being blown around by big fans—could easily be lifted by wires. The scene was shot with two cameras. Tsuburaya frequently employed multiple cameras—a technique often ascribed as Akira Kurosawa's signature brilliance—but, Tsuburaya filmed this way as well. After nearly 50 years, this effects scene still proves thrillingly impressive on the big screen in color in Tohoscope. A whole layer of comedy was added by the film being shown in its dubbed version.In one of the production stills where the two miniatures of the rocket ships are shown on the surface of the moon, Ragone pointed out how one of them looked a bit unfinished or rough because it was about to be blown up.

Introducing Mothra, Toho's largest scale kaiju eiga (monster movie), Ragone offered original concept designs of Mothra as a big horrible monster. The script was softened into something of a fairy tale by screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa who based his screenplay on the stories by Shinichiro Nakamura, Takehiko Fukunaga and Yoshie Hotta. The look of Mothra was adjusted accordingly. In a production still of Mothra in its caterpillar phase, a 30-foot costume manipulated by seven individuals, Ragone pointed out the meticulous background details of well-tended fields, which prove barely noticeable in the film itself. Sometimes the cameras were so low on the set, you couldn't see these details.

Introducing Mothra, Toho's largest scale kaiju eiga (monster movie), Ragone offered original concept designs of Mothra as a big horrible monster. The script was softened into something of a fairy tale by screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa who based his screenplay on the stories by Shinichiro Nakamura, Takehiko Fukunaga and Yoshie Hotta. The look of Mothra was adjusted accordingly. In a production still of Mothra in its caterpillar phase, a 30-foot costume manipulated by seven individuals, Ragone pointed out the meticulous background details of well-tended fields, which prove barely noticeable in the film itself. Sometimes the cameras were so low on the set, you couldn't see these details. Offering a production still of the 1:50 scale miniature set of the Shubiya ward ravaged by the larval Mothra, Ragone could confirm its "staggeringly perfect" accuracy, having lived there for a while. Though he didn't live there in 1961, many of the buildings are still there, like the Fuji Bank and the movie theatre. Shubiya had many movie theatres and—again emphazing Tsuburaya's near-insane mania for set detail—Ragone translates one of the movie marquees in the production still as Elmer Gantry.

Offering a production still of the 1:50 scale miniature set of the Shubiya ward ravaged by the larval Mothra, Ragone could confirm its "staggeringly perfect" accuracy, having lived there for a while. Though he didn't live there in 1961, many of the buildings are still there, like the Fuji Bank and the movie theatre. Shubiya had many movie theatres and—again emphazing Tsuburaya's near-insane mania for set detail—Ragone translates one of the movie marquees in the production still as Elmer Gantry.Ragone showed a slide of Tsuburaya on the massive set for New Kirk City, which Mothra attacks in the film's final sequence. New Kirk City is located in a fictitious Western country called Rolisica, which Ragone identifies as a combination of Russia and the United States. "Just because they didn't want to blame any one country for bombing Infant Island and releasing all that bad stuff that happens in the film; all that bad karma."

Columbia Pictures wanted a more spectacular ending to the film for distribution in the United States—the original ending was situated in the mountains of northern Japan—so they financed the tacked-on scene where Mothra attacks New Kirk City.

Columbia Pictures wanted a more spectacular ending to the film for distribution in the United States—the original ending was situated in the mountains of northern Japan—so they financed the tacked-on scene where Mothra attacks New Kirk City.The Peanut Sisters, twins Yumi and Emi Ito, were cast as Mothra's "Little Beauties". The reason Mothra was scored by Yuji Koseki and not Akira Ifukube—who customarily scored all of Toho's science fiction films—was precisely because Koseki had a longstanding working relationship with The Peanuts and because Tsuburaya wanted a more operatic score for the film.

Ragone stressed that the reason a film like Mothra did so well at the box office not only in Japan but in its import to the United States was because it was a good movie, with special effects that were state-of-the-art for the time. Forty years later a "little sense of wonder" might be required to appreciate Mothra; but—in my estimation—it doesn't take much; the film still whimsically enchants, especially in its original Japanese-language version.

Ragone was asked if he had ever considered writing a script with a new conception of Godzilla and submitting it to the Toho Studios? No, he replied. He's had friends in the past submit story ideas to Toho that were appropriated by Toho and worked into films they were already making without any kind of credit or compensation. Basically, he explained, the way Toho looks at it, if you're writing about Godzilla, they automatically own it. There are no intellectual property rights, especially if you're a little guy and not a big guy with deep pockets.

Ragone was asked if he had ever considered writing a script with a new conception of Godzilla and submitting it to the Toho Studios? No, he replied. He's had friends in the past submit story ideas to Toho that were appropriated by Toho and worked into films they were already making without any kind of credit or compensation. Basically, he explained, the way Toho looks at it, if you're writing about Godzilla, they automatically own it. There are no intellectual property rights, especially if you're a little guy and not a big guy with deep pockets.Preceding both films was a short Japanese documentary on Tsuburaya with a rich sampling of clips from his films that helped contextualize the rich value of his legacy.

Cross-published on Twitch.

Sunday, March 23, 2008

ON COMING FULL SPIRAL

"Coming full circle" is an inexact term. Though its sentiment of arrival can be appreciated, it implies a stasis, as if one has arrived and can finally stop. Thus, for me, "coming full circle" hints of death, completion. If—as a circle of sorts—the icon of the zero is the source from which all numbers flow, the circle of zero likewise references a fecund nothingness to which all things—perhaps indeed even the progress of numbers—return.

"Coming full circle" is an inexact term. Though its sentiment of arrival can be appreciated, it implies a stasis, as if one has arrived and can finally stop. Thus, for me, "coming full circle" hints of death, completion. If—as a circle of sorts—the icon of the zero is the source from which all numbers flow, the circle of zero likewise references a fecund nothingness to which all things—perhaps indeed even the progress of numbers—return.As a narrative indicator of the cycle of recursive life experience, perhaps it would be more exact to talk about "coming full spiral", as the precession of the equinoxes attests. Novelist Thomas Wolfe suggested you can never really go home again, and my own sojourns across the face of the planet have brought me back to familiar countries and cities and taught me that—even though coming back to the same place—the spiraling progress that forms identity as surely as it forms the nautilus shell confirms you are not the same person, not the same traveler, not really. The illusion of return, the illusion of the circle, the truth of illusion, belies a learning curve spiraling forward into time. The illusion is the shell we all carry on our very real backs.

I find myself back at the San Francisco C.G. Jung Institute at 2040 Gough Street across the street from Lafayette Park. I'm early for my seminar on the anima in film, so—after registering—I walk across the street to sit on a park bench facing the morning sun, as I used to do all those many weekend mornings during my 20s and 30s when I was a full scholar attending public programs at the Institute. It's been nearly 10 years since I've set foot in the Institute or attended a program there; what it took to draw me back was Dr. John Beebe teaching on film. And as I sit in the sun, I contemplate things.

I watch blossoms flutter off a cherry tree on a chance breeze. I contemplate the warrior spirit of blossoms. I watch a hummingbird zipping in and out among the branches of the blossoming tree and contemplate its roosting on a limb, resting, conserving the energy it must burn to fly. I contemplate the burnt energy of my own senescence sitting on this park bench in the morning sun. There remains, however, a warrior spirit within me that continues to solicit assistance from the sun and which employs human fugacity as an aesthetic weapon against the charge of inhuman time. I remember that in Nahuatl tradition the hummingbird is also a warrior for the sun whose long beak pierces the heart as surely as a spear pierces the enemy. (To find a lover, you place hummingbird feathers beneath your pillow.)

No, I don't place hummingbird feathers beneath my pillow. That wouldn't be hypoallergenic. Besides, I have had too many lovers in my life. "My body is a battlefield and I've got the scars to show." Shifting attentions—as one is wont to do in their later years—I have substituted my passions. I have chosen film. Films. Plural. My polyamory extends into celluloid. I can be loyal to no one film. I must fondle many. Eros makes handservants of the idle, they say, and apparently I have become one of those.

Screening Guy Maddin's Heart of the World and Jean Vigo's L'Atalante to state his thesis, Dr. Beebe projects the DVDs onto the Institute's white wall. This seems so apt, I have to smile to myself. Such "frenzy against the wall." I'm present not only because I love Maddin's six-minute founding myth of cinema, but because—as Girish Shambu has recently written at his eponymous site about a cinephile's accounting—I am lately drawn more to the old stories than the new ones.

I feel curiously beside myself attending this seminar; as if occupying two seats. I'm nearly embarrassed when Dr. Beebe grants me credence with his audience by advising them of The Evening Class. I'll be interviewing him soon in conjunction with the upcoming publication of his book studying the anima in film. I don't know why that seems so oddly resonant to me. I recall being in my mid-20s learning from him then and now being in my mid-50s preparing to interview him. Something about that just seems downright wondrous to me.

Full spiral indeed.

Friday, March 21, 2008

TCM: Jamaa Fanaka Doublebill

You gotta love Turner Classic Movies ("TCM") for respecting the breadth of the term "classic", applying it equally to silent films as to countercultural indies. Case in point: tonight's doublebill of Evening Class favorite Jamaa Fanaka, whose Emma Mae (aka Black Sisters Revenge, 1976) and Penitentiary (1980) are boasting their late night TCM premieres tonight at 11:00PM and 12:45AM PT, respectively.

You gotta love Turner Classic Movies ("TCM") for respecting the breadth of the term "classic", applying it equally to silent films as to countercultural indies. Case in point: tonight's doublebill of Evening Class favorite Jamaa Fanaka, whose Emma Mae (aka Black Sisters Revenge, 1976) and Penitentiary (1980) are boasting their late night TCM premieres tonight at 11:00PM and 12:45AM PT, respectively.I recently ran into TCM's Director of Programming, Charlie Tabesh, at the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival, and welcomed the opportunity to congratulate him on his continuing creative programming; not only the Val Lewton retrospective a month or so back, on which I piggybacked the Val Lewton blogathon, but the Charles Burnett showcase, tonight's Fanaka doublebill, and their upcoming June focus on Asian and Asian American representation in film. Let it be said in print that Charlie Tabesh is guiding the art of exhibition right into the 21st century by championing films that might otherwise never be seen. Though Fanaka's films might not align with everyone's notion of "classic", their historicity is unquestioned and their impact on independent filmmaking seminal. Kudos to Charlie Tabesh for recognizing same! And a loving shout-out to my man Jamaa for his television debut!

Cross-published on Twitch.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

SFIAAFF08—Hyazgar (Desert Dream, 2007)

A poetic spirit of perseverance is to be sifted from Lu Zhang's Mongolian sandscape Hyazgar (Desert Dream, 2007), the follow-up to his much-acclaimed Mang zhong (Grain In Ear, 2005). Significant carryovers exist: once again, Zhang focuses on a widowed Korean woman with a young son thrust by desperate circumstances into an interaction (if not quite a relationship) with a strange man. The names of mother (Choi Soon-hee) and son (Chang-ho) remain the same as those in Grain In Ear, which Zhang—in an insightful interview with Hoo-nam JoongAng Ilbo—explains as avoiding "the stress of finding a new name."

A poetic spirit of perseverance is to be sifted from Lu Zhang's Mongolian sandscape Hyazgar (Desert Dream, 2007), the follow-up to his much-acclaimed Mang zhong (Grain In Ear, 2005). Significant carryovers exist: once again, Zhang focuses on a widowed Korean woman with a young son thrust by desperate circumstances into an interaction (if not quite a relationship) with a strange man. The names of mother (Choi Soon-hee) and son (Chang-ho) remain the same as those in Grain In Ear, which Zhang—in an insightful interview with Hoo-nam JoongAng Ilbo—explains as avoiding "the stress of finding a new name." Stress avoidance aside, however, Zhang employs the Korean widow with child in tow and their refugee status as an iconic, albeit personalized, reference to division in Korea and relations with China. Widowhood, in fact, was a common occurrence during the Cultural Revolution when so many fathers were either thrown in prison or executed. Mother Choi—played by Jung Suh, known for her performances in Chang-dong Lee's Peppermint Candy; Kim Ki Duk's The Isle, Il-gon Song's Spider Forest and Cheol-su Park's Green Chair)—and her impudent son Chang-ho (Shin Dong-ho) arrive at the yurt of Hangai (Osor Bat-Ulzii) seeking food and shelter moments after his wife and daughter have left him to attend to the daughter's medical needs at a hospital in the big city. What develops between the Korean woman and her son and the Mongolian tree farmer is a tenuous cohabitation thinly guised as a surrogate family; a guise braced for survival against a desolate and formidable backdrop.

Stress avoidance aside, however, Zhang employs the Korean widow with child in tow and their refugee status as an iconic, albeit personalized, reference to division in Korea and relations with China. Widowhood, in fact, was a common occurrence during the Cultural Revolution when so many fathers were either thrown in prison or executed. Mother Choi—played by Jung Suh, known for her performances in Chang-dong Lee's Peppermint Candy; Kim Ki Duk's The Isle, Il-gon Song's Spider Forest and Cheol-su Park's Green Chair)—and her impudent son Chang-ho (Shin Dong-ho) arrive at the yurt of Hangai (Osor Bat-Ulzii) seeking food and shelter moments after his wife and daughter have left him to attend to the daughter's medical needs at a hospital in the big city. What develops between the Korean woman and her son and the Mongolian tree farmer is a tenuous cohabitation thinly guised as a surrogate family; a guise braced for survival against a desolate and formidable backdrop. Another carryover from Grain In Ear is a somewhat self-conscious camera technique of juxtaposing the overfamiliar with the unexpected. Grain In Ear's ongoing stasis provided the final scene's effectively startling movement. Again and again in Desert Dream, Zhang employs belated left-to-right and right-to-left camera pans to follow action after characters have walked into and out of initial frame-ups (a style FIPRESCI author H. N. Narahari Rao associates with Hungarian filmmaker Miklos Jancso). This proves to be a slightly distracting technique that draws attention to itself; but, achieves culmination in the film's final 360° rotation and a concluding image that—as Variety's Russell Edwards puts it—"is designed to have auds scratching their heads wondering, 'How did they do that?' " Though I could forego that question for an answer to what it essentially means. Of note is that the only time Zhang doesn't use this panning technique is when the handheld camera follows Choi into the desert on the few times she attempts to leave Hangai's yurt compound. "People who take refuge away from their homes are different from ordinary people," Zhang explains. "To depict their emotional state I used a handheld technique."

Another carryover from Grain In Ear is a somewhat self-conscious camera technique of juxtaposing the overfamiliar with the unexpected. Grain In Ear's ongoing stasis provided the final scene's effectively startling movement. Again and again in Desert Dream, Zhang employs belated left-to-right and right-to-left camera pans to follow action after characters have walked into and out of initial frame-ups (a style FIPRESCI author H. N. Narahari Rao associates with Hungarian filmmaker Miklos Jancso). This proves to be a slightly distracting technique that draws attention to itself; but, achieves culmination in the film's final 360° rotation and a concluding image that—as Variety's Russell Edwards puts it—"is designed to have auds scratching their heads wondering, 'How did they do that?' " Though I could forego that question for an answer to what it essentially means. Of note is that the only time Zhang doesn't use this panning technique is when the handheld camera follows Choi into the desert on the few times she attempts to leave Hangai's yurt compound. "People who take refuge away from their homes are different from ordinary people," Zhang explains. "To depict their emotional state I used a handheld technique."I am clearly not informed as to political and cultural particulars that would provide a better handle on this film; but, I'm grateful the film has made me aware of that sad fact, which I hope to respectfully remedy by subsequent research. Despite my own ignorance, however, the film retains a mesmeric charisma. The landscape of the Mongolian steppes is captivating in its barren windswept beauty.

Desert Dream had its world premiere at the 2007 Berlinale along with the similarly-situated Tuya's Wedding, which ended up attracting the most attention of the two, though Dinko Tucakovic in his FIPRESCI report complimented the "slow and talented" Lu Zhang for discovering "once again the varieties of the planet that we are sharing." It wasn't until the mid-summer Osian-Cinefan Festival of Asian & Arab Cinema that it gained rightful due, awarded the Best Picture prize by an international jury comprised of directors Hala Khalil from Egypt, Wu Tianming from China, Saeed Mirza from India, Thailand's Apichatpong Weerasethakul, as well as former Cannes festival programmer Francois Da Silva. Their decision was based on "the conviction with which Zhang Lu depicts the contemporary crisis of our time. He has found the right cinematic expression to tackle a theme of such great importance."

Desert Dream had its world premiere at the 2007 Berlinale along with the similarly-situated Tuya's Wedding, which ended up attracting the most attention of the two, though Dinko Tucakovic in his FIPRESCI report complimented the "slow and talented" Lu Zhang for discovering "once again the varieties of the planet that we are sharing." It wasn't until the mid-summer Osian-Cinefan Festival of Asian & Arab Cinema that it gained rightful due, awarded the Best Picture prize by an international jury comprised of directors Hala Khalil from Egypt, Wu Tianming from China, Saeed Mirza from India, Thailand's Apichatpong Weerasethakul, as well as former Cannes festival programmer Francois Da Silva. Their decision was based on "the conviction with which Zhang Lu depicts the contemporary crisis of our time. He has found the right cinematic expression to tackle a theme of such great importance." Accepting Zhang Lu's own clues, a better translation for the film's Mongolian title Hyazgar might have been "boundary", which sheds light on some of the themes Zhang is pursuing. "Nations have boundaries," he has said, "and so do people's minds. …Once the boundaries are diminished, minds can connect. A film, after all, is about states of mind." Communication—complicated by different languages and cultural customs—is in turn tempered by the humorous moments borne from culture clash. Chang-ho frequently amuses in his comments about how annoying it is that his Mongolian host doesn't speak Korean.

Accepting Zhang Lu's own clues, a better translation for the film's Mongolian title Hyazgar might have been "boundary", which sheds light on some of the themes Zhang is pursuing. "Nations have boundaries," he has said, "and so do people's minds. …Once the boundaries are diminished, minds can connect. A film, after all, is about states of mind." Communication—complicated by different languages and cultural customs—is in turn tempered by the humorous moments borne from culture clash. Chang-ho frequently amuses in his comments about how annoying it is that his Mongolian host doesn't speak Korean. The boundaries in Desert Dream are decorated with blue prayer ribbons. Just as Hangai's self-appointed vocation is to ward off the encroaching desertification of the Mongolian steppes—a shifting boundary measured by trees that will not grow and marauding military tanks that reflect prevailing realities—so the bridge that leads the film's North Korean refugees into their new South Korean home is given voice by blue flags ruffling in the incessant winds of change.

The boundaries in Desert Dream are decorated with blue prayer ribbons. Just as Hangai's self-appointed vocation is to ward off the encroaching desertification of the Mongolian steppes—a shifting boundary measured by trees that will not grow and marauding military tanks that reflect prevailing realities—so the bridge that leads the film's North Korean refugees into their new South Korean home is given voice by blue flags ruffling in the incessant winds of change. I wish I knew more the specific cultural meaning of the blue Mongolian prayer ribbons (and welcome feedback from anyone who does). I am aware that in the Lakota Sioux tradition, trees are perceived as praying figures with their branches like arms held up to the sky. It's not just that they are praying, it is that they are always praying, a difficult task, which anyone who stands with his arms uplifted can attest. Prayer ribbons essentially represent man's way of interacting with and taking part in the prayers of the tree, which by shamanic extension are the prayers of the culture. Prayer ribbons are tied to trees because life is ongoing. The tree is growing, the tree is praying. The wind moves the prayer ribbons. The relationship between that movement and the movement of the earth is related to the wind. Life is moving. When it stops it's dead. And that tree is praying every day as it moves in the wind. When you put a prayer into that prayer ribbon, it spreads it all across the earth.

I wish I knew more the specific cultural meaning of the blue Mongolian prayer ribbons (and welcome feedback from anyone who does). I am aware that in the Lakota Sioux tradition, trees are perceived as praying figures with their branches like arms held up to the sky. It's not just that they are praying, it is that they are always praying, a difficult task, which anyone who stands with his arms uplifted can attest. Prayer ribbons essentially represent man's way of interacting with and taking part in the prayers of the tree, which by shamanic extension are the prayers of the culture. Prayer ribbons are tied to trees because life is ongoing. The tree is growing, the tree is praying. The wind moves the prayer ribbons. The relationship between that movement and the movement of the earth is related to the wind. Life is moving. When it stops it's dead. And that tree is praying every day as it moves in the wind. When you put a prayer into that prayer ribbon, it spreads it all across the earth. Comparable to how trees were used for burials among the Lakota, I found it telling that—before finally leaving with his mother on the long journey "home" to South Korea—Chang-ho "buries" all the dead saplings by committing them to fire. This is where the shamanic substratum of Mongolian culture has affected our own Amerindian spiritual practices and why—with a minimum of dialogue—Desert Dream achieves a consummate level of storytelling.

Comparable to how trees were used for burials among the Lakota, I found it telling that—before finally leaving with his mother on the long journey "home" to South Korea—Chang-ho "buries" all the dead saplings by committing them to fire. This is where the shamanic substratum of Mongolian culture has affected our own Amerindian spiritual practices and why—with a minimum of dialogue—Desert Dream achieves a consummate level of storytelling.Here is the film's trailer, and a further video clip can be found at Vimeo (both without English subtitles, but sufficient to suggest the spirit of place and pace). The film has one more Bay Area screening in the festival this coming Saturday, March 22, 2008, 6:00PM at Berkeley's Pacific Film Archive.

Cross-published on Twitch.

04/19/08 UPDATE: Adam Hartzell offers some keen cultural insights in his review of Desert Dream for Koreanfilm.org.

Monday, March 17, 2008

SFIAAFF08—Om Shanti Om

Tremors of joyous lust nearly brought down the Castro Theatre last night as the audience for Om Shanti Om voiced their roaring approval. Here's why:

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

PEDRO COSTA (and Others) on Casa de Lava and Tarrafal, Part Two

In his Film Comment article on Pedro Costa, Thom Anderson describes Colossal Youth as "an intentionally imperfect film … that is loosely constructed and almost certainly obscure, which creates unfortunate difficulties for some viewers. You probably have to see it at least twice to get it, and to me that is not a virtue." Compounded by Costa's forthright admission that he is still discovering the film himself and that one of his main actors had to explain a major plot point to him at its Cannes premiere, Anderson generously sets virtue aside and suggests: "Perhaps it can be a film in progress for us as well, as we watch it and think about it later. Its construction allows us to shift scenes around and remake it in our heads." (Film Comment, March/April 2007, Vol. 43:2, p. 61.)

In his Film Comment article on Pedro Costa, Thom Anderson describes Colossal Youth as "an intentionally imperfect film … that is loosely constructed and almost certainly obscure, which creates unfortunate difficulties for some viewers. You probably have to see it at least twice to get it, and to me that is not a virtue." Compounded by Costa's forthright admission that he is still discovering the film himself and that one of his main actors had to explain a major plot point to him at its Cannes premiere, Anderson generously sets virtue aside and suggests: "Perhaps it can be a film in progress for us as well, as we watch it and think about it later. Its construction allows us to shift scenes around and remake it in our heads." (Film Comment, March/April 2007, Vol. 43:2, p. 61.)In my case, I definitely had to watch Colossal Youth twice and each viewing was a distinct experience; the first befuddled and bedazzled and the second distanced and alert. The same could be said about Costa's short Tarrafal, which I initially caught as part of the O Estado do mundo (State of the World) omnibus at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Although I appreciated it well enough when I first saw it—"Pedro Costa's Tarrafal is an equally powerful film with its allusions to the Tarrafal prison on Santiago Island, Cape Verde. Its narrative moves forward first through cautionary ancestral tales regarding the inescapable summons of death and then through the voices of ghosts who remember their tortured past. It is a political tract rendered exquisitely as a haunting ghost story. Its short length is amplified by textural density."—I didn't fully appreciate Tarrafal until my second viewing, deepened by Costa's commentary.

Introducing the film, Costa identified Tarrafal as the village on Santiago Island, Cape Verde, off the coast of Senegal, where in 1936 the Portuguese came up with the idea of creating a prison patterned after the Nazi concentration camps. Many of the Cape Verdeans he now works with were born in Tarrafal and come from that part of the island.

Tarrafal addresses a social issue "we" all face, namely deportation and expulsion. "It's happening all over Europe," Costa explained, "Here, I don't know, it's the Mexicans I think; [but,] it's happening all over Europe, in France, in Spain, in England, in Portugal." He and his crew experienced it firsthand when one of the young actors who has been in all his films, José Alberto Silva, was recently served his deportation papers, despite his having been born in Portugal. To offset Silva's upset, Costa offered to channel funds received from Lisbon's Calouste Gulbenkian Museum—intended to finance a 15-minute film for the State of the World project—into making a film about Silva's deportation. (Coincidentally, the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum is the same museum pictured in Colossal Youth, which Costa included to address and redress the issue that Ventura—who was one of the contractors who built the museum—had never been allowed access.)

Costa decided that the theme of involuntary deportation fit perfectly within an examination of the state of today's world, especially for the disenfranchised and marginalized. "I think it's a horror movie," he explained, "That we made very quickly at the beginning of last year."

The film's setting is important because—at the actors' request—they didn't want to do yet another film in the housing project, neither in Silva's apartment nor Ventura's. "Where do you want to shoot then?" Costa asked them and they said they weren't sure but they wanted it to be away from the apartments. So they walked across the highway to a clearing where there was some tall grass and a gnarled tree and decided to film there. That's when the relevance of this decision dawned on Costa. It was as if the actors themselves, the subjects of the film, were saying that through a series of displacements—first from Cape Verde to Fontainhas in Lisbon, then from the relocation from Fontainhas to Casal Boba, and then the eviction from Casal Boba and deportation from Portugal—they had become complete refugees with no home to call their own. All they could claim was a patch of earth and the open sky. They wanted the film to be a protest of the conditions—the heaviness—foisted upon them and whose burden they must shoulder.

Again, the theme of weight, of gravitas, or—as Costa himself said it in his Tokyo seminar "A Closed Door That Leaves Us Guessing" (published in Rouge 10, 2005)—"Filmmaking is a very real and serious profession. Serious means heavy, and sometimes the weight of things can be very heavy. The weight of feelings is something to handle with balance and common sense, and so we must never laugh when somebody speaks about God or the Devil. In effect, when we speak of God or the Devil in cinema, we're speaking about good and evil, we're talking about people. We're speaking about ourselves, about the Devil and the God in us, because there's no God up on high, and no Devil below."

Again, the theme of weight, of gravitas, or—as Costa himself said it in his Tokyo seminar "A Closed Door That Leaves Us Guessing" (published in Rouge 10, 2005)—"Filmmaking is a very real and serious profession. Serious means heavy, and sometimes the weight of things can be very heavy. The weight of feelings is something to handle with balance and common sense, and so we must never laugh when somebody speaks about God or the Devil. In effect, when we speak of God or the Devil in cinema, we're speaking about good and evil, we're talking about people. We're speaking about ourselves, about the Devil and the God in us, because there's no God up on high, and no Devil below."Costa has frequently asserted that he wants to create a cinema that deals with "what is not working", which is to say a socially responsible cinema that looks at "where the evil lies between you and I, between me and somebody else, so we can see the evil in society, and so we can search for the good."

In "A Closed Door That Leaves Us Guessing" Costa likewise compares scenes from Jacques Tourneur's Night of the Demon and Robert Bresson's Money, wherein cursed pieces of paper are exchanged to reference "what is not working." This shed considerable light on Tarrafal where—along with the folk tale Silva's mother tells him of a man who delivers death messages on pieces of paper—the government's deportation notice becomes a commensurate cursed piece of paper. When I asked, Costa confirmed the Tourneur connection.

"Tarrafal is a remake of Jacques Tourneur's Night of the Demon," he offered, "where there is this strange parchment that is passed by this very strange man called Karswell—the Devil is called Karswell in this film—and he passes this [parchment] to Dana Andrews, who is a skeptic, a very cold, rational man. This paper actually says [he has]—I don't know how many—maybe 12 hours to live. So [Tarrafal] is moreorless the same story."

Though his friend José Alberto Silva was born in Portugal, his mother Lucinda Tavares—seen in the film—was born in Tarrafal. In Casa de Lava Costa included a scene of the Tarrafal cemetery and the hospital that used to be the Guardians' ward. When they began thinking about this story with this evil letter, this deportation notice from the Minister that you see in the end, Costa recalled Tourneur's film. "It's good the classics," Costa smiled, "because you can go to one of them. It's like Godard. You just have to pick one and everything comes."

Actually, he remembered Night of the Demon when José Alberto's mother was telling her folktale about the man in Cape Verde who had this evil, wicked way of passing a death message to people. The original idea was to make a 15-minute film where José Alberto would say good-bye to a lot of things—his mother, some friends—and in the first scene they shot, where José Alberto and his mother are sitting down and conversing, José Alberto was supposed to say good-bye to his mother. As customary, they filmed the scene every day for a week, José Alberto and his mother Lucinda sitting down in this shack talking, from 9 to 1, then they'd break for lunch, and continue filming from 2 to 6. After a week of filming, they still hadn't said good-bye to each other. They didn't want to. They loved each other too much.

To ward off the good-bye, Lucinda began telling José Alberto this story in one of the takes and it was then Costa remembered the Tourneur film. That's when they associated the cursed paper that delivers death with the notice of deportation.

"Being that you have moreorless paid homage to Jacques Tourneur in two of your films and have described him as a great artisan," I asked Costa, "can you qualify what it is that you admire so much in Tourneur's work?"

Costa described that he had something of a schizophrenic split between Jacques Tourneur on one side and Staub and Huillet on the other. Though this is all right for a film lover, Costa said it was "very dangerous for a filmmaker to have a Straub/Tourneur [split]. Sometimes I'm very dizzy. Not long ago, when Danièle [Huillet] was still alive, I forced [her and Jean-Marie Straub] to tell me some things about Tourneur, because they never talked about him. Actually, they liked some of his films. What they like[d] was the craftsmanship, not only Tourneur but a lot of filmmakers that were just—like I said—artisans, responding to the producers—'You have to do this and this and this'—some of course, like Tourneur, could bring in the films something more. But all of them, they're all very good, they were all so good with space. This side I have of Tourneur [that] is dark, mysterious, romantic or poetic, I cannot help it. The girl can't help it. [Costa chuckled.] But it will stay there. I saw a lot of films by Tourneur when I was young, and not only the ones more related to ghosts or like that. There's a very very beautiful one that is not a Western but almost, it's called Stars in My Crown [1950]. In Tourneur's films they speak in very low voices. They're quiet films. They're almost fading all the time. When I was younger, I loved Tourneur because I had the feeling that I didn't know if the films could go on to the end, they had this fading effect. I was afraid they would disappear; they're so slow."

Argentine film critic Quintín has written that for Costa, Jacques Tourneur and the Straubs "are kindred spirits, even if one is known as a spiritualist cult follower while the others are famously committed materialists. Costa claims that such categorization is nonsensical, and that both Tourneur and the Straubs, as well as Ozu, Ford, Lang, and other classical filmmakers, share the same vision of cinema, one based on precision and truth." (Cinema Scope 25, Winter 2006, p. 67.)

Critical Overview of Tarrafal

Acquarello's write-up of Tarrafal for Strictly Film School is, without question, the most respectful, insightful and thorough; correctly perceiving the outdoor setting "as a metaphor for Pedro Costa's densely layered themes of dislocation and statelessness" and "the state's arbitrary dispensation of deportation and eviction notices in modern day Portugal" as the "impersonal, life-altering communication" of the "blood-sucking phantasm who foretells a person's hour of death by surreptitiously leaving letters in the most mundane of hiding places to be subsequently retrieved at the time of their immutable appointment." Moreover, Acquarello defines a "sense of surrogacy and transplantation", which is to say that José Alberto's fate—his involuntary deportation—is one that could equally be had by any of the Cape Verdeans at Casal Boba. Their helplessness in the face of the State is interchangeable. Again, exile is imprisonment. Acquarello concludes: "[T]hese parallel testimonies of dislocation, separation, entrapment, and fatedness unfold through supplanted images of interchangeable, moribund, drifting ghosts that integrally reflect their own erasure and social invisibility."

Daniel Kasman notes that Tarrafal continues "the aesthetic and production technique Costa has used since In Vanda's Room, but like the jump between that film and Colossal Youth, Costa seems to be distancing his later films from that movie's 'purer' documentary impulse, adding layers of obliqueness, mystery, and cine-influences more overtly." It would be difficult to find a better description of the gradual evolution of Costa's Tourneur/Straub split.

Daniel Kasman notes that Tarrafal continues "the aesthetic and production technique Costa has used since In Vanda's Room, but like the jump between that film and Colossal Youth, Costa seems to be distancing his later films from that movie's 'purer' documentary impulse, adding layers of obliqueness, mystery, and cine-influences more overtly." It would be difficult to find a better description of the gradual evolution of Costa's Tourneur/Straub split.

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

PEDRO COSTA (and Others) on Casa de Lava and Tarrafal, Part One

The pairing of Pedro Costa's second feature Casa de Lava (1994) with one of his more recent shorts Tarrafal (2007)—Costa's contribution to the State of the World omnibus—was a deft stroke of curation; both films light a candle to the influential spirit of Jacques Tourneur.

Observing that connection, I will now divide my observations into two (perhaps even three) entries for purposes of discussion, commiserating with the exchange between Darren Hughes and David McDougall at Dave's site Chained to the Cinémathèque regarding the inadequacy of the short blog entry format to contain all that can and should be said about Costa's work. I will instead take Andy Rector's indispensable cue at Kino Slang and develop my thoughts over a series of angled entries.

Casa de Lava was the first (and only) film Costa made on the archipelago of Cape Verde—specifically the island of Fogo (which translated means "fire")—an island which is basically a big, dark, dormant volcano. One of the things Costa found beautiful about Fogo was that its inhabitants lived in the crater, some 500-600 meters high, and were mostly women; the men having left the island to pursue work in Portugal or Boston. He commented that there is a sizeable Cape Verdean community in Brooklyn.

Casa de Lava is a film Costa made quite a while back at a time when he was not feeling good about living in Lisbon, let alone Portugal. He was "probably" not feeling very well with himself, and had this idea of going away to, perhaps, relax. Mark Peranson's Cinema Scope interview details more fully the sources of Costa's discontent and how it led to his assignment on Fogo, where he found that these people and this place mysteriously and sensitively restored him to many things he believed missing from his country and his people. It was upon completion of Casa de Lava that he was given letters and gifts to deliver to relatives and friends in Fontainhas, which proved key to his future projects.