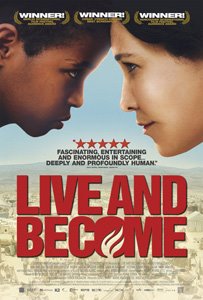

One of the central spotlights of this year's San Francisco Jewish Film Festival was the plight of the Falasha, Ethiopian Jews and Jews of Color, a topic of which I was wholly ignorant. My first exposure to this astounding historical phenomenon was Radu Mihaileanu's Live and Become, the epic closing night feature for the festival and a monumental drama about a young Ethiopian boy Schlomo from a Sudanese refugee camp who is transported to Israel as part of Operation Moses, during which 8,000 Ethiopian Jews were airlifted in 1984 to begin new lives. The film won the 2006 César for Best Original Screenplay and both the Panorama Audience Award and Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 2005 Berlinale.

The role of Schlomo was played by three different actors—Moshe Agazi, Moshe Abebe, and Sirak M. Sabahat—Schlomo as a child, a teenager, and a man, respectively. It was my great honor to meet with 24-year old Sirak M. Sabahat during the run of the festival. We met hat to hat at the Ninth Street Film Center. He was wearing a stovepipe and I my Makins shortbrim. After complimenting each others' hats, we sat down to talk and I have to admit it was one of the most engaging conversations I have had with anyone anywhere. I feel blessed to have met this young man.

* * *

Michael Guillén: Congratulations on a solid strong performance in Live and Become and for its festival success. It's done very well. My understanding is it's your first main acting role in a film?

Sirak M. Sabahat: I've done a few things before I've done this film. I've done a lot of theater and t.v. but it was my biggest role. This film was very successful around the world and this film was spread among the theaters and among festivals, so I've never had this kind of attraction and this kind of relation.

MG: It's also my understanding that it's a film that speaks to your own experience. As an Ethiopian Jew, you must have been proud to be able to tell this story to the world because most of us know nothing about this.

SS: No. At the beginning when I saw the script and when I saw what the film was going to be about, I had a lot of difficulties. I had to think what I'm going to do this film. Because it was similar to my story and I had to recreate my life again, recreate the emotion that I had in the past. As you know, I did not have to do research for the film because I was the research. But also I was just one of those stories. I am just one of the thousand of stories among the Ethiopian Jews. There are many stories like me. There are many exodus stories like me. In my case I was so proud because I had the privilege to take a part in something that was huge, something that was done for the first time, something that's talking about ideas. Today, when you see, people will not sacrifice their life for an idea anymore. Or they will sacrifice their life for an idea if they are extremists. But what I'm saying is when you sacrifice your life for something good, for something that you really believe. So this film it was for me to educate also the audience but at the same time to come into contact with the audience that doesn't know anything about other people's lives and for me it was also I was educated by their response and the way they were educated by me. So I've been giving and I've been blessed to receive at the same time. It's a big privilege to be in the front of a stage and to tell the story of your community.

SS: No. At the beginning when I saw the script and when I saw what the film was going to be about, I had a lot of difficulties. I had to think what I'm going to do this film. Because it was similar to my story and I had to recreate my life again, recreate the emotion that I had in the past. As you know, I did not have to do research for the film because I was the research. But also I was just one of those stories. I am just one of the thousand of stories among the Ethiopian Jews. There are many stories like me. There are many exodus stories like me. In my case I was so proud because I had the privilege to take a part in something that was huge, something that was done for the first time, something that's talking about ideas. Today, when you see, people will not sacrifice their life for an idea anymore. Or they will sacrifice their life for an idea if they are extremists. But what I'm saying is when you sacrifice your life for something good, for something that you really believe. So this film it was for me to educate also the audience but at the same time to come into contact with the audience that doesn't know anything about other people's lives and for me it was also I was educated by their response and the way they were educated by me. So I've been giving and I've been blessed to receive at the same time. It's a big privilege to be in the front of a stage and to tell the story of your community.MG: Your exodus was with Operation Solomon?

SS: Yes.

MG: Can you speak a little bit about that? Or do you feel you need to speak about that? Has it been said for you through this film?

SS: Operation Solomon happened as you know in 1991. It was a coproduction, I would say, of the United States and Israel to save and to bring 50,000 Ethiopian Jews in three days. It was an amazing operation. In three days the Israeli government got inside Ethiopia and took the people to Israel. We didn't know that we were going to Israel. But my story and my journey started like any other Ethiopian Jew. I started to walk from my village with my family to the capital city of Ethiopia. Our journey lasted one year. Because imagine, when you're walking, you must rest at the same time. You must restore your powers. You must eat and there are sicknesses. If one of my brothers was sick, we had to stay as long as he got better so we can continue. Each time we were praying that no one would be sick but once my brother was sick and my sister too.

This journey was taking too much time and there was a shortage of food. At the same time there was a threat to our life because in Africa, as you know, slavery still exists and slavery for sex, sex slavery for ladies, we were afraid that we can be captured by those groups and to be [sold] to many fanatic people that can do whatever they like. So you have many dangers. It's not just to face starvation, to face illnesses, and to face the people who are coming in front of you. You must find a different kind of strength to survive this journey. The human body cannot adjust himself to this kind of times because it is unbelievable. So we were eating leaves. I felt like animals to stay alive. But you need something much more deeper than the leaves and than your personal thing that you drink just to keep you alive. You must have some kind of vision. You must have some kind of faith that is greater than your life itself. So we had this Jerusalem, this utopic idea that we want to be in the land of our fathers one day. You will give anything. So many people die on the way, they will sacrifice their life on the way just to reach to that point.

This journey was taking a year because my father was also the navigator, I would say. Sometimes he didn't know where he was going. We were always returning to the same place. I want to say to my Mother, "I remember this place because we have been in this place before." And my Mother warned me with her eyes, don't say anything, he's a man and a man doesn't want to have any direction from a woman at any time, at this time and that time. But when we came to Addis Ababa we were so amazed to see that we were saved by a miracle. And then the operation happened. They put us in a bus and they say you are going—not to travel, because no one knew that we are leaving Ethiopia—but I could see that people starting to throw the bread and the little money they had to the population. I said to myself, "Why those poor people would give the last thing they have to those starving people also?" So I was asking maybe we are going to some different place? But I wasn't thinking about Israel.

When we came to the airplanes, you see this big bird and you think to yourself, "Oh my God, God is here with this bird to take us to the Holy Land." Because it was the first time that we saw airplane. And to try to understand the gaps between the Ethiopian Jews and this world, you must understand there is a 400-years gap. It's like bringing someone from the 19th century to this moment exactly and explain to them something about computers. Something the mind cannot understand.

MG: It must have been terrifying!

SS: It was terrifying. We were on the plane and I was asking who was holding the plane? Everybody was asking who was holding the plane? Because how this huge thing can be in the air? I am lighter than the plane so why I cannot fly? And this heavy thing is in the air. It was a rational question. A question of discovery. When we landed to the land of Israel and they told us that we are in the land of Israel, we didn't believe that we have the opportunity that we will be in the Holy Land in our lifetime. There are moments when the excitement was enormous so people bowing down and kiss the ground.

But when I saw white people, I was so in shock because no one told me there was white Jews. So when we did this change, we did it also to save the Judaism in this world. But when I saw many of white people, I said, "Oh my God they have skin problem. Those poor people!" [Laughs.] Later on I saw a million of them. I said, "Oh my God, this disease is spreading so fast." And then I saw that maybe I have the skin problem now because I was the minority. You come from a place that you are the majority; now you become a minority. To explain to you in the best way, people in Africa—Christians for example—they don't see Jesus with blue eyes and blonde hair. They see Jesus with curly hair and big nose and big lips, the way we are in Africa. This is the way you see it, according to your image. You're describing the higher power according to your place. If you are created in this way, probably that person who created or that spiritual leaders in the skies or heaven, they must look like you in a way. This was the perception that you were raised with. This was the perception that you understand and you cannot change it. But when you come to a different society, to the new world, to Israel, everything was different. God was different, according to their eyes. The prophets were different. Things were different.

MG: The movie does a fine job of showing the tension of that realization, and then the process that Ethiopian Jews had to go through to try to adjust. For yourself, what led you then into acting? You obviously knew you had to survive. You had to learn how to do something in the Holy Land, in this new world. What led you to acting?

SS: There's two stories about these things but the first one is there was a girl that I liked in school. She was amazing. I was in love with her in secret for two years and one day I said to myself, "I must do something special for this lady." So I worked very hard and I bought a very expensive present. I returned to the school. It was recess time. I asked her to talk to her. She came. She approached me. I was trying to express my feelings but I didn't know how to do it because I still had difficulties to socialize with the new world. I said, "Okay, this present will prove my attention for you." I gave her the present. She opened the present and after five seconds she started to scream and to laugh. She disappeared faster than Superman from my place. I didn't understand what was wrong and people was laughing. One of the guys, the students, came to me, "Are you crazy? You're giving to this girl two kilos of beef?!" [Laughs.] My idea was in Africa if you're giving something like this, something valuable, something meat, it showed that you appreciate that person so much. It was an enormous thing. But for her it was, "What the hell this guy's doing? In the middle of the day he's got a two kilo gift in his pocket?" But for me it was a special gift. But after she denied those gift, I was offended. I said, "I need to do something else."

And then I saw on the screen a boy chasing after a girl. So I thought I would have a better chance to do so on the screen. But it started in this way. And then I started to discover what is a theater, what is a cinema. I said to myself, "This is a place that you can speak in own voice, that you can express everything that you want, because people wants me to be a doctor, a lawyer, everything. Then I understand that in theater and cinema you can be all of those things. You can be whatever you want and you can influence those people and you can shape people['s] mind[s] in a good way, a good humanity. But people say to me, "You know what is acting?" I say, "What is acting?" "If you do acting in this world, you will starve the way you would starve in Ethiopia. This is the closest example." I said, "So if I'm going to choose acting, I'm going to starve the way I was starving in Ethiopia, but in the new world?" "Yes." They were trying to say to me, "Don't do this, because it's impossible." But this is my destiny. I have been survive many things. I have been seeing many things in my entire life. And my mother said you need to do things that will make you happy.

MG: And the fact that you were given an opportunity really to express your story the best way it's probably going to be expressed. I understand also that you had a lot to do with the direction, especially the scenes that had to do with Ethiopia. How was that?

SS: The director Radu Mihaileanu, he's amazing for me because you are coming to do a film in a language you don't understand. You have the music to understand when it's supposed to be this, when it's supposed to be that, but it's very courageous to do a film in a language that you don't understand. So when he came to do his film, I was trying to find my own voice in the cinema. I had difficulties. I was always typecast for Miss Scarlett part. "Whatever you say, Miss Scarlett." I didn't want to do those things because I didn't [see] myself as an actor for every part. I went to write my own plays. After I wrote my own plays, people understand that I have a different kind of talent so they started to notice.

When the director came, I said to him, "Listen, this film is very important for you and for me. After we understand that we need to do it. But in order to do this, we need to cooperate in a hard way. So I will deal with the writing in the [Ethiopian] part. I will deal with the direction with the kids, with all the children casting. Because I had experience of directing. And he understand that I have a vision and I have a mind and we was so serious that he was trusting so much because he's a very strong director, and no one open his mouth on the set when he's doing something, and no one stops. He's very tough. When people saw that I was doing, "Cut! Action!" "My God, you do?" "Yes." Because we had some kind of understanding. I want to do the best film. Not just as an actor. As a director, as a writer, as an acting coach, because this film, it's about my community so it was important for you to come and to do this exodus about different people, different lives. For me it's much more important to give the 100%. I wasn't care about … I was on the set on the days I wasn't supposed to be, I was in the shooting at the beginning. So we started to collaborate on this film because we found a similar voice, me and the director.

In the beginning it was very hard when I work with people—even though I had a reputation a little bit among the Ethiopian communities. I had to work with the kids, for example, so I was very tough with them, "I'm going to direct you. You need to do this. You need to do that." And I was working with the kids that were staying with me for a long time. Just to understand the psychology, the gesture, things that they're doing. When we were on the set, he was sitting behind a monitor directing the Ethiopian scenes. I was there to say, "Okay, you're going to do this way and you're going to do that way." He completely understand that we are on the same level and the same understanding. So he didn't tell me you shouldn't. I know because I can bring the images because I know the story, I have been living it. Maybe you got a great imagination but imagination according to real reality is something different.

MG: In terms of the acting coaching, it's my understanding that you coached the two Moshes that played your character at younger ages? You actually coordinated all three of your performances so they would align character-wise?

SS: Yes.

MG: How did you go about that? Did you make them be like you?

SS: No. The secret for me was not to try to teach them anything. Not to try to tell them you need to do this and you need to be similar. I had to see them and to learn from them because they are children. They are not actors. It was very hard to say to them, "Be like me." It's the opposite. I need to be like them because I have the ability to take the way they are and then to mix it with my way.

They were staying in my apartment for a long time. We were working about the scenes, every scene particular in acting way—you know the first scene when the mother is sending him, every aspect, what we do, the hugging part, the monologues, the dialects. I was trying to tell them, "Don't try. Just say these things from your own way." The problem is with children when you are working you cannot give too much description: "Listen, this was a day like this and you are very sad and you are like this." Children, they don't understand a lot of metaphors. You cannot speak to the children in a picture way. You must give them direct[ion]: "You are sad in this moment." That child will [be] sad in a moment because he knows what to get sad. Tell to a child you are happy; he will [be] happy in a moment. He will not ask you, "What kind of happy? Happy happy? Less happy?" [Laughs.] This work with them, I was very tough with them, when I work with all the Ethiopians, when I work with the two Schlomos. At the end of the day the result was for me when I saw them on the set, when I said "Action!" They brought everything that we work on it in my little studio, in my little apartment.

MG: They were astounding performances, all three of you.

SS: Thank you.

MG: I must single out, however, the performance of Mosche Agazai, who plays Schlomo as a child. I was impressed. He had to carry the movie to further it, to get it to where Mosche Abebe and you could take it. He did a fine job. Is this what you hope to do more of: directing and writing?

SS: I will not write if I do not have anything to say. If I will write again, I will write because I feel this is a burning issue for me. Because I want to educate the people in different ways. My hopes, my wishes for the future, I'm not a regular actor who do films and will be in the covers, all this paparazzi thing. For me cinema is a valuable place that you can use to shape and to tell stories and there is many true and heroic and amazing stories in this world. I want to do films that can influence these people. When they will go out from the cinema, I want them to debate a little bit, I want them to ask questions, I want them to feel close, I want them to be upset, I want them to have everything that I'm having as a person.

MG: That certainly happened for me with this film because I was sitting there going through that entire range of emotions. The film generated many questions. What is the situation now for Ethiopian Jews? Has it changed much? Is it still the same problem of finding a place in Israeli society? Have White Jews become any more tolerant? What is going on?

SS: As you know, if you are a minority it doesn't matter where you are, you will suffer. Not because you deserve it, because you are a minority and you have a different way of life. People [are] ignorant and they will not accept it. I had to face with a lot of racism in Israel and my community had to face with a lot of racism but racism, as we understand now, is beginning to be so common thing around the world. Here in the United States, in Europe, in Israel, it's everywhere. What I understand is this is a disease of human beings. This is a mental disease like any other disease in this world. You need treatment. You need to take the things that you need to take in order to be fine. You are sick if you are racist. Whether you are black, white, yellow, it doesn't matter. We are coming with a lot of shapes and forms.

When I was in university, I was the president of Ethiopian students. There [were] many times that student[s] were fighting against racism and one time I said, "This is enough. Stop. We need to approach different kinds of ideas." My life was saved because many good people gave their heart and soul to me. My community life was saved because a lot of good people that sacrificed, that took a danger to save us. The force of good is still the greater force in this world. Those fanatic will always say that. Those racist people will always be there. Why to put our spotlight on waste cause when you can create a better humanity with those who are with one foot forward already?

MG: Sort of like you were saying to have even survived the exodus from Ethiopia, you had to believe in something larger than yourself.

SS: Exactly.

MG: And now you're saying the same thing, that in order for all of us to survive the racism in the world, we have to believe in a better force.

SS: I'm saying don't wait for organization to change your lives. Don't wait for government to save your life. You have the responsibility to shape the things according to you. People who do not accept you now will not accept you forever. People say, yes, I after a while I accept this man because I understand differently. No. If you are not given the possibility to a human being, it doesn't matter where it is as a human being, and open your heart to him as a human being without to ask any question. He's rich, stupid, it doesn't matter, he's a human being standing in front of you. If you cannot open your heart and accept that person at the beginning so you have issues. The racist people they cannot accept me even though they can understand that what they are doing it is stupid. To ask the question of why there was people who believe in the death of other people. Why the Nazis kill 7 million Jews and why to those Nazis you still have people who continue these kind of things here in Minneapolis in Minnesota or in different [places]. What make those people to continue or to follow these crazy ideas? How can you fight those people? You will take them, you're going to make diplomats, you wait to say, "Listen. You must accept people"? If this thing doesn't come naturally, what can you do about it? So don't waste your power. Put your power in the places that can create a better humanity and not in a place that can create a barriers with human beings.

MG: In tandem with that, often the worse prejudices come from your own kind. As you've traveled around the world with this film, you've obviously met different Black communities of various Black faiths, has there been a response? Anything you can say about that?

SS: The Black people here, for example, they love the film, they adore the film, because the identity problem now is the issue. Who am I? Where I'm coming from? The Blacks didn't choose to come to the United States. They were brought here. When the slavery thing started to happen, the amount of the people that arrived to the United States was a very low percent. The major[ity] of slaves went to the Carribean or to other places. They were asking themselves, "Who am I? Where I'm coming from? I want to return to search my mother or to my roots but I cannot go to my roots. I know I am Black, I know from Africa, but where in Africa?" The question of identity is relative to any of us. So the Black Americans they very much love this film. They are very supportive, feel related to the subject.

MG: So are you saying the theme of searching for identity is more important than any kind of specific racial identification? All of us are searching for identity? All of us are displaced people?

SS: Exactly. Because it's a displaced world in this moment. Look what's happening.

MG: The other day I interviewed Amos Gitaï. Do you know Amos?

SS: Yes, I know Amos. We're friends.

MG: I was struck by Amos because—between his films that I saw at this festival and your film—I feel like my mind has been popped open. We just do not get an accurate picture through our media. We are told of a conflict that we have to accept because it is all we know. Through cinema, through movies, filmmakers present a complexity to the issue that makes the issues more human. Filmmakers help Americans begin to suspect that there are Israeli and Palestinians who are not investing in this conflict. There are people all throughout Israel who are not investing in their national product through the media. I have to thank you as a person who is creating film. I agree with you 100% that cinema is a form of education. My website was inspired by Sembene. I call it The Evening Class. Because when I saw his films, they impressed me so much that I started researching him and I was struck by his statement that for African adults cinema is the evening class. That's where they go to see reflected the social and political issues that are of importance to them. That has been my focus with movies: what do I learn from a film?

SS: I have a question for you.

MG: Okay.

SS: Imagine, when there's a rumor, one slice of rumor, and in the other hand is a good thing that you did in your life. You have two things. There is a rumor and there are good things that you done. Put those things together and spread those things among your friends, what do you think will conquer the most? What do you think the most influential thing will be?

MG: The rumor.

SS: Why is that?

MG: Because I think that surprisingly the power of light has to operate enshrouded, as within a darkness, whereas the power of darkness has high visibility.

SS: Why is that? As a human, why are we attracted to that place and not to the good place? Why?

MG: I want to believe in my own faith that it's because the power of light—in order to achieve its most brilliant aspect—must constantly be challenged. It must have constant adversary. I am 52 years old and I have studied racism and classism….

SS: You look great!!

MG: Thank you, it's the hat.

SS: It's more than the hat.

MG: I have studied these things my entire life and I cannot come to any answer other than that, for some reason, it is meant to be this way or is inherent in the human animal. Perhaps conflict is archetypal and like all organic constructs, archetypes must evolve. That evolution is our human challenge. I liked what you said: that rather than getting caught up in ideology and fighting a force that you really can't win, you have to create the other world. You have to be the exponent of the other world. That's how I would answer your question. It's like a candle flame creates so much trembling shadow but it's the candle flame that is the source of both brightness and darkness. Darkness is not the source of the candle flame. We need to remember sources.

SS: They are speaking about this conflict nowadays, the conflict with Lebanon and everything that happened over there. I was seeing the media before the war happened. All the media—the newspapers and t.v., the anchors, all of them—the only question they were asking was, "Is there going to be a war?" You have a responsibility to talk about things. You have a responsibility to shape minds. The responsibility that they have is so enormous. It's like they are pushing themselves. "When are there going to be a war between Israel and Lebanon? Who's going to win? The force of Israel is this. The force of Hezbollah." You are eager to push people in a war. You are eager to take people in that position to create some interesting moment in this area but now look what happen after they been bombing, after the strike, people start to speak, "There are a lot of innocent people dying." What did you expect when you sing a war? A war is not a playing field that you go to play soccer and you will return wounded and a day after you can walk. In war you are counting those who survive, not those who are dying, and it is hypocrite for me to say and to push.

MG: What do you expect when you sing a war. That's a lovely articulation. I sing: In my mind I can't study war no more. For myself, when our President first began referencing the axis of evil and the war on terror, I decided then and there I would no longer listen to this nationalized propaganda, this hate speech. I've stopped reading newspapers and I don't watch television news because subtraction is an effort towards spirit. For me media representations are a false story. And it doesn't much matter if I forsake my duty in keeping up with these things by a daily dose of the media because I don't need to. Everyone else does. Between boldface headlines and the ubiquitous gossip on the street, I know what's going on, or what the media says is going on. When I was talking with Amos, he confirmed that these are false stories and the more you believe in them, the more you invest in them, the more you further them. I've turned to film at this stage in my life because I believe that creative energies such as your's, such as Amos', they tell me more about the potential that the world really has to offer, more potential than the media allows. I'll wrap it up here because I know you have others waiting to interview you.

SS: No. This talk is opening my mind. They can wait. On the other hand, you cannot ignore, I am not saying to ignore from those fanatic people because those racist people will come in the end of the day to harm those who are trying to create a better humanity. But the things that the media coverage is, you cannot ignore the newspaper, you cannot ignore the media because they are shaping every day a million people's lives. It's like when I was seeing t.v. the way they were presenting Israel before the war in the time of the conflict, that man with the stone, they're presenting this story of the weak against the strong, David against Goliath, and I was thinking they are so full of it because people are choosing to believe in the images they see on t.v. So my question was: people are not intelligent enough to discover themselves, to educate themselves what is truth and what is false?

MG: Or—in the movie, an image I thought was so beautiful—they show a little Ethiopian boy watching the television, transfixed. Then the camera pans around to reveal that all the other kids are behind the television set, discussing their concerns: how did the people get into the box and when are they going to come out? We each have to bolster and explore our own realities; the realities that are of importance to each of us. No one reality works for all of us. And if there's to be any examination of truth and falsehood, it must fall within the realm of this multiplicity of experience.

SS: Exactly. I will wrap it with this story. When we came to Israel, instead of going to Jerusalem they took us to the north of Israel and they put is in the hotel. I'm telling you I was so amazed by the room in the hotel because it was so clean and beautiful. The first time that I saw a toilet, I asked myself, "What is that thing?" My mother came to me and she said, "No one is going to be close to this white and beautiful thing." She saw the toilet as it was a private museum. And then I was asking, "Why is this thing in white? Why this thing is not in brown?" You've got a lot of questions. And then the first time that I saw a t.v. like those child, I waited with my friend three days to see when the people were going to sleep. [Laughs.] No one went to sleep. I see big houses, big things, and I said, "How they put those things inside?" There is a gap of 400 years. Your mind is traveling. I don't understand. You're upset. You're searching awake. When my mother saw the first time the t.v., you know what she said? She said, "We have guests inside the house." So she sent me to grocery to buy a coffee for them. I went from the house, walking to grocery, and I was thinking, "My mother doesn't understand that the people inside of the t.v., they are not guests. They are there to stay forever." [Laughs.] In her eyes when she opened the t.v. she saw people so she said, "We have guests. So go." Who am I to tell to my mother, "You are wrong. You are mistaken." Even though I know. It's been 12 years. When I came to Israel I was 12 years old. I didn't know to read and write in my personal language. In my previous life I was a hunter, in agriculture, I was a farmer. And today I do films and I speak more than five languages. I understand when people speak also about Africa, they're saying about Africa a place without possibilities but I'm saying this is a place without tools. Once you give the tools to human beings, they will do many great things and we are the proof.

MG: Well, you definitely are the proof of it and I thank you very much for the time. I think you should write your story even more, it is so rich, it has so much for all of us to hear. Just what you've said is something that we need to know here in this country where tools have been provided to us from the moment we're born and we don't know what to do with them. Thank you very much.

SS: My pleasure.