Long-time bud Mike Black—with whom I have spun a vinyl or two—offers three YouTube oldie goldies. Thanks, Mike!

Sister Rosetta Tharpe: Up Above My Head

Millie Small: My Boy Lollipop

Bobby Vee: The Night Has A Thousand Eyes

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

INDIAN SILENT CINEMA—3rd i's "Snakes, Sirens & Vamps: A Short History of Early Indian Cinema"

One of the spectatorial pleasures of K.M. Madhusudanan's Bioscope (2008) was its revelatory glimpse into Indian Cinema's silent film corpus, by way of Dadasaheb Phalke's 1918 Hindi "mythological" Shri Krishna Janma (Birth of Lord Krishna). Bioscope screened at the 2008 3rd i South Asian Independent Film Festival, where I wrote it up, and initiated a volley of emails between myself, New Delhi journalist Jai Arjun Singh (Jabberwock), and Anuj Vaidya, Associate Festival Director for 3rd i, anticipating a seminar on the history of Indian Silent Cinema. Short of a year later, that seminar has finally arrived.

One of the spectatorial pleasures of K.M. Madhusudanan's Bioscope (2008) was its revelatory glimpse into Indian Cinema's silent film corpus, by way of Dadasaheb Phalke's 1918 Hindi "mythological" Shri Krishna Janma (Birth of Lord Krishna). Bioscope screened at the 2008 3rd i South Asian Independent Film Festival, where I wrote it up, and initiated a volley of emails between myself, New Delhi journalist Jai Arjun Singh (Jabberwock), and Anuj Vaidya, Associate Festival Director for 3rd i, anticipating a seminar on the history of Indian Silent Cinema. Short of a year later, that seminar has finally arrived.This coming Friday, July 24, 2009, 3rd I and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival will co-present a lecture by Anupama Kapse: "Snakes, Sirens and Vamps: A Short History of Early Indian Cinema." Kapse's lecture, illustrated with clips, and with live musical accompaniment by Robin Sukhadia for select clips, will provide a welcome opportunity "to see rare excerpts from some of the earliest films from the subcontinent, including: Kaliya Mardan (1919), by India's film pioneer D.G. Phalke, about the exploits of a young Krishna; Gallant Hearts (1931), 'a fast and furious comedy-action-adventure film, filled with court intrigues, rowdy sword fights, and fantastic locations', modeled after The Thief of Baghdad (1924); films from the legendary Bombay Talkies studio; and early sound films like Achut Kanya (1936) and Aadmi (1939)."

Anupama Kapse will provide an introduction to each film, and lead her audience through a short history of early Indian cinema, from the silent era into the arrival of sound on the Indian filmscape. All films will be presented in a digital format; since most of these films have not been restored, and the quality of some of the clips duly reflect the archival nature of the prints.

Anupama Kapse will provide an introduction to each film, and lead her audience through a short history of early Indian cinema, from the silent era into the arrival of sound on the Indian filmscape. All films will be presented in a digital format; since most of these films have not been restored, and the quality of some of the clips duly reflect the archival nature of the prints.Kapse's doctoral thesis, The Moving Image: Melodrama and Early Cinema in India, 1913-1939, examines the genres of Indian silent cinema through a melodramatic lens. She is currently co-editing a collection of essays, Border Crossings: Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (with Jennifer Bean and Laura Horak, forthcoming Indiana University Press), inspired by last Spring's UC Berkeley symposium "Border Crossings: Rethinking Silent Cinema." Prior to joining the PhD. program in film studies at UC Berkeley, Kapse taught at Gargi College, University of Delhi, India, where she was Assistant Professor of English. She has lectured widely on silent cinema in India and works on film history, gender and the visual culture of "Bollywood." This fall, she will be joining Queens College as Assistant Professor in media studies.

Bollywood film music fanatic Robin Sukhadia completed his Master of Fine Arts at the California Institute of the Arts. He has been studying tabla under Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri at CalArts and the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael, California for the past seven years. His special focus on the musical traditions and rhythms of South Asia informs his approach to musical arrangement and composition on a wide range of concert, film and album productions. For the past five years, Robin has traveled internationally on behalf of Project Ahimsa, an organization committed to empowering impoverished youth through music education. In 2008, Robin presented a three-part talk, "Bollywood Sound & Image: A discussion with Robin Sukhadia", as part of 3rd i's ongoing Speaker Series.

Bollywood film music fanatic Robin Sukhadia completed his Master of Fine Arts at the California Institute of the Arts. He has been studying tabla under Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri at CalArts and the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael, California for the past seven years. His special focus on the musical traditions and rhythms of South Asia informs his approach to musical arrangement and composition on a wide range of concert, film and album productions. For the past five years, Robin has traveled internationally on behalf of Project Ahimsa, an organization committed to empowering impoverished youth through music education. In 2008, Robin presented a three-part talk, "Bollywood Sound & Image: A discussion with Robin Sukhadia", as part of 3rd i's ongoing Speaker Series."Snakes, Sirens and Vamps: A Short History of Early Indian Cinema" will take place Friday, July 24, 2009, at the Mission Cultural Center (2868 Mission Street); $8-$10 (tickets at the door only).

Cross-published on Twitch.

SFJFF09—Eight Michael Hawley Screener Previews

The 29th San Francisco Jewish Film Festival (SFJFF) begins this Thursday, July 23 and continues through August 10 at various Bay Area venues. You'll find me at the Castro Theater much of this coming weekend, catching some of the festival's most highly-anticipated titles like Defamation, The Yes Men Fix the World and Acné. Meanwhile, here are capsule write-ups of eight films I previewed on screener, roughly in order of most favorite to least.

The 29th San Francisco Jewish Film Festival (SFJFF) begins this Thursday, July 23 and continues through August 10 at various Bay Area venues. You'll find me at the Castro Theater much of this coming weekend, catching some of the festival's most highly-anticipated titles like Defamation, The Yes Men Fix the World and Acné. Meanwhile, here are capsule write-ups of eight films I previewed on screener, roughly in order of most favorite to least. Zion and His Brother—Director Eran Merav makes an assured feature film debut with this gritty, affecting family drama set in working-class Haifa. Fourteen-year-old Zion both worships and despises his older brother Meir, a hot-headed miscreant who makes life miserable for their divorced mother and her older boyfriend. When tragedy erupts over mistaken identity and a stolen pair of shoes, Zion is forced to reevaluate his allegiances and life direction. The performances are first-rate, particularly the never-less-than-amazing Ronit Elkabetz (The Band's Visit, Late Marriage, Or) as the mother, and a remarkably intense Ofer Hayan, making his screen debut as the older brother. I'm still pondering the film's abrupt ending.

Zion and His Brother—Director Eran Merav makes an assured feature film debut with this gritty, affecting family drama set in working-class Haifa. Fourteen-year-old Zion both worships and despises his older brother Meir, a hot-headed miscreant who makes life miserable for their divorced mother and her older boyfriend. When tragedy erupts over mistaken identity and a stolen pair of shoes, Zion is forced to reevaluate his allegiances and life direction. The performances are first-rate, particularly the never-less-than-amazing Ronit Elkabetz (The Band's Visit, Late Marriage, Or) as the mother, and a remarkably intense Ofer Hayan, making his screen debut as the older brother. I'm still pondering the film's abrupt ending. Yoo-Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg—Chances are you've never heard of broadcasting pioneer Gertrude Berg, a writing-acting-producing powerhouse who was once the highest paid woman in America. That's an embarrassment Aviva Kempner handily sets right in this breezy, informative documentary. Debuting on radio one month after the 1929 crash, her family sit-com The Goldbergs gave comfort to Americans throughout the Great Depression and WWII, with her character Molly Goldberg yoo-hoo-ing to neighbors from across her Bronx apartment airshaft window. The program brought Jewish family life into millions of homes, and was second in popularity only to Amos and Andy. In 1949 the show made the switch to TV, which resulted in Berg winning the first ever Emmy Award for acting (she'd also win a Tony Award in 1959 for A Majority of One). Kempner's film does a winning job of profiling Berg, from her youth in the family's Catskills resort hotel, to her fierce defense of blacklisted actor and union activist Philip Loeb, the actor who played her husband Jake Goldberg. At the July 28 screening at the Castro, Kempner will receive this year's SFJFF Freedom of Expression Award. And if you want to see more of The Goldbergs, there's a separate festival program comprised of four back-to-back episodes of the TV show.

Yoo-Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg—Chances are you've never heard of broadcasting pioneer Gertrude Berg, a writing-acting-producing powerhouse who was once the highest paid woman in America. That's an embarrassment Aviva Kempner handily sets right in this breezy, informative documentary. Debuting on radio one month after the 1929 crash, her family sit-com The Goldbergs gave comfort to Americans throughout the Great Depression and WWII, with her character Molly Goldberg yoo-hoo-ing to neighbors from across her Bronx apartment airshaft window. The program brought Jewish family life into millions of homes, and was second in popularity only to Amos and Andy. In 1949 the show made the switch to TV, which resulted in Berg winning the first ever Emmy Award for acting (she'd also win a Tony Award in 1959 for A Majority of One). Kempner's film does a winning job of profiling Berg, from her youth in the family's Catskills resort hotel, to her fierce defense of blacklisted actor and union activist Philip Loeb, the actor who played her husband Jake Goldberg. At the July 28 screening at the Castro, Kempner will receive this year's SFJFF Freedom of Expression Award. And if you want to see more of The Goldbergs, there's a separate festival program comprised of four back-to-back episodes of the TV show. The Wedding Song (Closing Night Film)—A Jewish girl and Muslim girl, best friends and both of marriageable age, are the protagonists in Karin Albou's powerful new film set in 1942 Nazi-occupied Tunis. Nour desperately wants to wed her finance Khaled, but until he finds employment they must settle for clandestine rooftop trysts arranged by her Jewish friend Myriam. Myriam, on the other hand, is being forced by her increasingly desperate mother (played by the director) into an arranged marriage with the arrogant, wealthy Jewish doctor Raoul (a reliably terrific Simon Abkarian). Meanwhile, the radio blasts anti-Semitic propaganda, Khaled gets a job helping Nazis round up Tunisian Jews and Raoul is sent to a labor camp—all of which tests the girls' loyalties and courage. With one brief exception, Albou sets her film exclusively within the claustrophobic confines of the Tunis medina, effectively mirroring her characters' constricted circumstances. She also takes pain to ensure that her male characters are not one-dimensional monsters—except for the Nazis of course. Finally, I was delighted to hear, of all things, Nina Hagen's Naturträne being used as a musical leitmotif throughout.

The Wedding Song (Closing Night Film)—A Jewish girl and Muslim girl, best friends and both of marriageable age, are the protagonists in Karin Albou's powerful new film set in 1942 Nazi-occupied Tunis. Nour desperately wants to wed her finance Khaled, but until he finds employment they must settle for clandestine rooftop trysts arranged by her Jewish friend Myriam. Myriam, on the other hand, is being forced by her increasingly desperate mother (played by the director) into an arranged marriage with the arrogant, wealthy Jewish doctor Raoul (a reliably terrific Simon Abkarian). Meanwhile, the radio blasts anti-Semitic propaganda, Khaled gets a job helping Nazis round up Tunisian Jews and Raoul is sent to a labor camp—all of which tests the girls' loyalties and courage. With one brief exception, Albou sets her film exclusively within the claustrophobic confines of the Tunis medina, effectively mirroring her characters' constricted circumstances. She also takes pain to ensure that her male characters are not one-dimensional monsters—except for the Nazis of course. Finally, I was delighted to hear, of all things, Nina Hagen's Naturträne being used as a musical leitmotif throughout. A History of Israeli Cinema—At 210 minutes long, this documentary won't appeal to anyone with a mere casual interest in its subject matter. But if you've spent the past 10 years watching Israeli cinema develop into one of the most vital in the world (my own starting point was Amos Gitai's 1999 Kadosh), this doc will provide you with an essential, evolutionary roadmap. From early Zionist works to the "New Sensitivity Cinema" of the 60's to the art films of today, director Raphaël Nadjari skillfully demonstrates how the nation's psyche has been continually reflected in its cinema. Broken into two parts (1933-1977 and 1978-2007), the film never strays from its staid film-clips-and-talking-heads format—and that's OK. My only complaint is that the ample clips are not identified by year of release, making it somewhat difficult to envision a timeline.

A History of Israeli Cinema—At 210 minutes long, this documentary won't appeal to anyone with a mere casual interest in its subject matter. But if you've spent the past 10 years watching Israeli cinema develop into one of the most vital in the world (my own starting point was Amos Gitai's 1999 Kadosh), this doc will provide you with an essential, evolutionary roadmap. From early Zionist works to the "New Sensitivity Cinema" of the 60's to the art films of today, director Raphaël Nadjari skillfully demonstrates how the nation's psyche has been continually reflected in its cinema. Broken into two parts (1933-1977 and 1978-2007), the film never strays from its staid film-clips-and-talking-heads format—and that's OK. My only complaint is that the ample clips are not identified by year of release, making it somewhat difficult to envision a timeline. I Am Von Höfler—Hungarian documentarian Péter Forgács is a SFJFF regular, which culminated in his receiving last year's Freedom of Expression Award. In his singular style, he tells stories of 20th century European Jews using only narration, sound effects, photos, letters, home movies and ephemera. His remarkable subject this time out is one Tibor Von Höfler—heir to a Pécs leather tanning dynasty who was also a motorcycle enthusiast, erotic photographer, womanizer and pianist—and whose long life bore witness to the Great Depression, WWII (he was half-Jewish on his mother's side) and the rise and fall of communism. Forgács' engrossing new film pieces together a seamless biography, giving the viewer a vivid sense of time and place, customs and mores. It has been hypothesized that an 18th century relative of Von Höfler's served as the inspiration for Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. In the film's only misstep, Forgács inserts clips from a dated, hippie-ish 1976 short called Werther and His Life, directed by his Balázs Béla Film Studio cohort, Janos Xantus. These clips pop-up throughout, adding incongruity and bloat to the 160-minute running time.

I Am Von Höfler—Hungarian documentarian Péter Forgács is a SFJFF regular, which culminated in his receiving last year's Freedom of Expression Award. In his singular style, he tells stories of 20th century European Jews using only narration, sound effects, photos, letters, home movies and ephemera. His remarkable subject this time out is one Tibor Von Höfler—heir to a Pécs leather tanning dynasty who was also a motorcycle enthusiast, erotic photographer, womanizer and pianist—and whose long life bore witness to the Great Depression, WWII (he was half-Jewish on his mother's side) and the rise and fall of communism. Forgács' engrossing new film pieces together a seamless biography, giving the viewer a vivid sense of time and place, customs and mores. It has been hypothesized that an 18th century relative of Von Höfler's served as the inspiration for Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. In the film's only misstep, Forgács inserts clips from a dated, hippie-ish 1976 short called Werther and His Life, directed by his Balázs Béla Film Studio cohort, Janos Xantus. These clips pop-up throughout, adding incongruity and bloat to the 160-minute running time. Lost Islands—This was Israel's biggest box office hit of 2008 and it's easy to see why. It's a big, rambunctious family dramedy set in the early '80s with a catchy pop soundtrack. The first half is almost cartoonish in its depiction of family squabbles and teen antics, the latter perpetuated by a pair of unlikely twin brothers who lust after the same classmate. The film takes on emotional weight, however, after a tragic accident causes dreams to be deferred, and the First Lebanon War threatens to destabilize the family and a nation. This is no art film, but it is broad, populist filmmaking at its most enjoyable—with terrific performances, offbeat humor and a genuine love for its characters.

Lost Islands—This was Israel's biggest box office hit of 2008 and it's easy to see why. It's a big, rambunctious family dramedy set in the early '80s with a catchy pop soundtrack. The first half is almost cartoonish in its depiction of family squabbles and teen antics, the latter perpetuated by a pair of unlikely twin brothers who lust after the same classmate. The film takes on emotional weight, however, after a tragic accident causes dreams to be deferred, and the First Lebanon War threatens to destabilize the family and a nation. This is no art film, but it is broad, populist filmmaking at its most enjoyable—with terrific performances, offbeat humor and a genuine love for its characters. A Matter of Size (Centerpiece Film)—Four overweight Israeli men find self-acceptance in sumo wrestling. That's the unique premise of this agreeable, but strictly formulaic comedy which is unsurprisingly on track for a Hollywood remake. Due to his weight, hulking Herzl has lost his job and been 86-ed from his dieting club. Inspired by a televised sumo match at a Japanese restaurant (where he now works as a dishwasher, and whose owner is conveniently a former sumo trainer), he convinces his friends to take wrap themselves in a mawashi and start rasslin'. In the conflicted process, life lessons are learned and romance blooms for all involved. If you've enjoyed plucky British arthouse comedies of recent years (think The Full Monty, Calendar Girls, Waking Ned Devine), you'll probably like this. If not, you probably won't.

A Matter of Size (Centerpiece Film)—Four overweight Israeli men find self-acceptance in sumo wrestling. That's the unique premise of this agreeable, but strictly formulaic comedy which is unsurprisingly on track for a Hollywood remake. Due to his weight, hulking Herzl has lost his job and been 86-ed from his dieting club. Inspired by a televised sumo match at a Japanese restaurant (where he now works as a dishwasher, and whose owner is conveniently a former sumo trainer), he convinces his friends to take wrap themselves in a mawashi and start rasslin'. In the conflicted process, life lessons are learned and romance blooms for all involved. If you've enjoyed plucky British arthouse comedies of recent years (think The Full Monty, Calendar Girls, Waking Ned Devine), you'll probably like this. If not, you probably won't. Hello Goodbye—Last and least comes this strained, unconvincing farce about a non-observant Parisian gynecologist (Gerard Depardieu) and his convert wife (Fanny Ardant) starting life anew in Israel. With the deck stacked against them from the get-go (his job vanishes, their condo remains unbuilt and their shipping container falls into the Mediterranean), the film bludgeons drama and yuks out of Israeli bureaucracy, his circumcision and her infatuation with a studly, pot-smoking young Rabbi (a wasted Lior Ashkenazi). A jarringly erratic and inappropriate pop music soundtrack (Peter Bjorn and John's Young Folks plays against a praying scene at the Wailing Wall) compliments the narrative like a berserk iPod shuffle. In contrast, the SF Chronicle's Mick LaSalle found the film to be "funny," "perceptive" and "illuminating." Perhaps you will, too.

Hello Goodbye—Last and least comes this strained, unconvincing farce about a non-observant Parisian gynecologist (Gerard Depardieu) and his convert wife (Fanny Ardant) starting life anew in Israel. With the deck stacked against them from the get-go (his job vanishes, their condo remains unbuilt and their shipping container falls into the Mediterranean), the film bludgeons drama and yuks out of Israeli bureaucracy, his circumcision and her infatuation with a studly, pot-smoking young Rabbi (a wasted Lior Ashkenazi). A jarringly erratic and inappropriate pop music soundtrack (Peter Bjorn and John's Young Folks plays against a praying scene at the Wailing Wall) compliments the narrative like a berserk iPod shuffle. In contrast, the SF Chronicle's Mick LaSalle found the film to be "funny," "perceptive" and "illuminating." Perhaps you will, too.Cross-published on film-415 and Twitch.

Sunday, July 19, 2009

WRAPPING OSHIMA

I've been living with Nagisa Oshima since late May and now find myself a bit melancholic that James Quandt's retrospective is leaving North American shores for Europe. I can't say that I caught every film in the series—even if I might have desired to; I was out of the Bay Area for a large middle section of its Pacific Film Archive stint—but, I caught enough to familiarize myself with Oshima's work and anticipate filling in the blanks come future opportunities. I likewise hope in future weeks to respond in writing to what I was fortunate enough to see.

I've been living with Nagisa Oshima since late May and now find myself a bit melancholic that James Quandt's retrospective is leaving North American shores for Europe. I can't say that I caught every film in the series—even if I might have desired to; I was out of the Bay Area for a large middle section of its Pacific Film Archive stint—but, I caught enough to familiarize myself with Oshima's work and anticipate filling in the blanks come future opportunities. I likewise hope in future weeks to respond in writing to what I was fortunate enough to see. Without question, the foreground experience was being invited by Susan Oxtoby to interview James Quandt during his visit to the Bay Area. Much like Girish Shambu owes his "cinephilic coming of age" to Quandt, my conversation with him bumped the word "autodidact" to the top of my favorite words list and has me seriously questioning the current festival practice of reviewing "films" by DVD screener (without responsible and requisite caveat).

Without question, the foreground experience was being invited by Susan Oxtoby to interview James Quandt during his visit to the Bay Area. Much like Girish Shambu owes his "cinephilic coming of age" to Quandt, my conversation with him bumped the word "autodidact" to the top of my favorite words list and has me seriously questioning the current festival practice of reviewing "films" by DVD screener (without responsible and requisite caveat).At Critical Culture, Pacze Moj offered a dissenting voice against the Oshima retrospective, primarily objecting to a comment made on the PFA website that few of Oshima's films were available on DVD or video. "Few films on DVD or video?" he writes, "Really? How odd: we Internet-generation peoples must be living in the future! ...because all but one of the feature-films playing in the retrospective are available online, through bittorrent or emule or both." Pacze then provides links to where the films in the retrospective can be downloaded onto computer. He likewise defends the new cinephilia, which doesn't demand in-cinema experience. We've agreed to disagree on this point of contention, though I would be interested to know how many writers actually use bittorrent or emule to download movies for review? I had always objected to the investment of time but Pacze argues: "[P]atience might depend on how you download. Emule can be slow, but a well-seeded torrent is quicker than going to the cinema, quicker than Netflix, quicker than driving to the video store." Pacze Moj's entry is particularly noteworthy for his links to Berkeley's CineFiles project, which I incorporate here for ready reference.

Tom Luddy's eight-page booklet from a 1972 Oshima retrospective. My eyebrow raised when I noted that films were only 75¢ back then!

Tom Luddy's eight-page booklet from a 1972 Oshima retrospective. My eyebrow raised when I noted that films were only 75¢ back then!David Owens' four-page booklet to a 1982 retrospective also called "In the Realm of Oshima".

Ian Buruma and Audie Bock's 23-page booklet from an Oshima retrospective held at the Hong Kong Film Festival.

Saturday, July 18, 2009

Thursday, July 16, 2009

ECCENTRIC CINEMA: COMING APART (1969)—A Critical Overview

When I consider the term "eccentric", I think of the orbits of comets, irregularly-shaped pearls, and the conversation I had with my ex-employer when our relationship began to deteriorate and she complained that my "eccentricity credits had run out." Four years later, I have to ask: "Can eccentricity credits ever really run out?" Or more importantly, should they? I think not! And I consider it highly irregular of her to think so.

When I consider the term "eccentric", I think of the orbits of comets, irregularly-shaped pearls, and the conversation I had with my ex-employer when our relationship began to deteriorate and she complained that my "eccentricity credits had run out." Four years later, I have to ask: "Can eccentricity credits ever really run out?" Or more importantly, should they? I think not! And I consider it highly irregular of her to think so.Now—due to the programming efforts of Pacific Film Archive's Steve Seid—to the term "eccentric" I associate cinema. "Eccentric Cinema: Overlooked Oddities and Ecstasies, 1963–82", currently running at PFA through August 27, 2009, states Seid's case: "Eccentric cinema thrives on pictorial surplus, the indulgent storyline, and a contempt for the customary, all resting upon the sagging shoulders of extravagant skill. This is no trash cinema, with its cheesy topics, uninvited camp, and joyful ineptitude. Instead, eccentricity might show itself as a dizzy disregard for the stuff of genre and style, or in the pursuit of ungainly ideas that consign a filmmaker to the status of outsider. Often the eccentric surfaces early in a career, before the artist has lost the exuberance of youth or succumbed to the timidity of the marketplace."

With "trashy" cinema now popularized and relegated to the academic footnote, eccentric cinema comes along to stake a claim on the side margins, clinging fiercely to that empty space for fear of slipping down to the bottom of the page for enumerated consideration. Steve Seid has constructed a veritable "Noah's Ark of oddities", shepherding two of each kind of subgenre into his confabulated series: "a pair of Westerns in which heroism has gone south; two postapocalyptic tales where virility prevails; dual vampiric accounts that suck, differently; a brace of psychological breakdowns involving mawkish men with issues; a duet of rock musicals that strike discord with their delivery; and a twosome of fantasies about that elusive thing called love, one with a mermaid, the other with a monomaniac." Seid concludes: "Genre meltdowns, faulty parables, self-detonating critiques: these films may not be trash cinema, but they are definitely worth recycling."

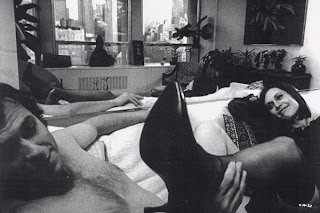

With "trashy" cinema now popularized and relegated to the academic footnote, eccentric cinema comes along to stake a claim on the side margins, clinging fiercely to that empty space for fear of slipping down to the bottom of the page for enumerated consideration. Steve Seid has constructed a veritable "Noah's Ark of oddities", shepherding two of each kind of subgenre into his confabulated series: "a pair of Westerns in which heroism has gone south; two postapocalyptic tales where virility prevails; dual vampiric accounts that suck, differently; a brace of psychological breakdowns involving mawkish men with issues; a duet of rock musicals that strike discord with their delivery; and a twosome of fantasies about that elusive thing called love, one with a mermaid, the other with a monomaniac." Seid concludes: "Genre meltdowns, faulty parables, self-detonating critiques: these films may not be trash cinema, but they are definitely worth recycling." I caught the series' first installment Coming Apart (1969) where Rip Torn—in his first starring role as one of the "mawkish men with issues"—"earns his moniker." As Seid writes: "He's ripped and torn and on the way to a big, bawdy breakdown in [Milton Moses] Ginsberg's voyeuristic sex romp. Torn plays Joe Glazer, a psychiatrist whose pent-up proclivities find him moving into a studio apartment in the building where his former mistress (Viveca Lindfors) lives. Once there, he begins a seduction 'experiment' that involves a one-way mirror, a couch, and a procession of sexually apt young women. Succumbing to his own predatory appetite, Joe becomes horrified by the emptiness of his conquests. His comeuppance arrives in the person of a former patient, played by a desperately determined Sally Kirkland, who deflates his fragile fantasy. Scorned at the time of its release, this prodding pic may have captured the painful collapse of sixties counterculture with too much provocation. Filmed entirely from behind the mirror, Ginsberg's frisky fete makes us voyeurs at our own love-in. The eyes have it."

I caught the series' first installment Coming Apart (1969) where Rip Torn—in his first starring role as one of the "mawkish men with issues"—"earns his moniker." As Seid writes: "He's ripped and torn and on the way to a big, bawdy breakdown in [Milton Moses] Ginsberg's voyeuristic sex romp. Torn plays Joe Glazer, a psychiatrist whose pent-up proclivities find him moving into a studio apartment in the building where his former mistress (Viveca Lindfors) lives. Once there, he begins a seduction 'experiment' that involves a one-way mirror, a couch, and a procession of sexually apt young women. Succumbing to his own predatory appetite, Joe becomes horrified by the emptiness of his conquests. His comeuppance arrives in the person of a former patient, played by a desperately determined Sally Kirkland, who deflates his fragile fantasy. Scorned at the time of its release, this prodding pic may have captured the painful collapse of sixties counterculture with too much provocation. Filmed entirely from behind the mirror, Ginsberg's frisky fete makes us voyeurs at our own love-in. The eyes have it." Coming Apart strips away the pleasure of voyeurism to reveal its addictive implication. Seid confirmed this in an email when I complimented him on his introduction: "What I was getting at but never managed to articulate about Coming Apart has to do with the reception of the film. I was referring to the voyeurism as an important theme. What I think riled many critics is not the sometimes gratuitous sexuality, nor its parade of neurotic nudes, but the fact that the film continually implicated the viewer. It seems to me that taboo things fare better when they just appeal to our base instincts. Everyone agrees that we have base instincts and base instincts indulged act as social release valves. But if you somehow complicate the use of base instincts, if you turn the impulse into a critique of abuse or power, then those instincts no longer function as release valves, but as subterfuge. In this context, the baser things critique their own source in culture. They become subversive. Coming Apart continually turns the mechanism of Rip Torn's voyeurism back on the audience. There is that great moment when he is remorseful that he can't turn off the machine even though he knows he must, that he's being self-destructive. But his compulsion is greater (at that moment) than his despair. And we as viewers can't stop watching him and his exploitation. That's just part of the film's intent, but it's pretty good stuff."

Coming Apart strips away the pleasure of voyeurism to reveal its addictive implication. Seid confirmed this in an email when I complimented him on his introduction: "What I was getting at but never managed to articulate about Coming Apart has to do with the reception of the film. I was referring to the voyeurism as an important theme. What I think riled many critics is not the sometimes gratuitous sexuality, nor its parade of neurotic nudes, but the fact that the film continually implicated the viewer. It seems to me that taboo things fare better when they just appeal to our base instincts. Everyone agrees that we have base instincts and base instincts indulged act as social release valves. But if you somehow complicate the use of base instincts, if you turn the impulse into a critique of abuse or power, then those instincts no longer function as release valves, but as subterfuge. In this context, the baser things critique their own source in culture. They become subversive. Coming Apart continually turns the mechanism of Rip Torn's voyeurism back on the audience. There is that great moment when he is remorseful that he can't turn off the machine even though he knows he must, that he's being self-destructive. But his compulsion is greater (at that moment) than his despair. And we as viewers can't stop watching him and his exploitation. That's just part of the film's intent, but it's pretty good stuff." When Coming Apart was first released in 1969, Time characterized Joe's "experiment" as "a voyeur's version of Candid Camera. The analyst analyzed, the schizoid psyche caught flagrante delicto—it is a notion worthy of Pirandello or Antonioni. And totally beyond Milton Moses Ginsberg…."

When Coming Apart was first released in 1969, Time characterized Joe's "experiment" as "a voyeur's version of Candid Camera. The analyst analyzed, the schizoid psyche caught flagrante delicto—it is a notion worthy of Pirandello or Antonioni. And totally beyond Milton Moses Ginsberg…."When Time complained that the transvestite character was "presumably added to assure the widest possible audience appeal", they were being condescending of course, though time lends a piquant reading to Joe's latent homosexual impulses, suspected by his peers. Is Coming Apart a misogynistic film? Probably not, though the demarcation is slight. Is Joe a misogynist? Perhaps a self-loathing misogynist: "I hate men, they degrade you for being a female." Is Coming Apart a homophobic film for the way Joe treats the transvestite when his anatomical secret is revealed? Perhaps only in the sense that misogyny has long been credited as the seat of homophobia. Contrary to Time's smarmy insinuation, there is appeal in recovering this transvestite character in '60s cinema for no other reason than it reinforces the project of archiving representation. He's a character consigned to the ranks of some of the minor players in Midnight Cowboy. M.M. Ginsberg has left a time capsule that—no matter how you judge the container—contains some far out stuff from the sixties; perhaps most notably an uncomfortable record of its capsized idealism.

At The New York Times, Vincent Canby noted that—though Rip Torn's character moves the camera several times—"for most of Coming Apart the camera remains focused on the couch and the mirror. As a result, almost every image is half real, half the reverse of reality, which is, I suppose, a legitimate cinematic equivalent of the way one automatically supplements reality with fantasy in conscious experience."

At The New York Times, Vincent Canby noted that—though Rip Torn's character moves the camera several times—"for most of Coming Apart the camera remains focused on the couch and the mirror. As a result, almost every image is half real, half the reverse of reality, which is, I suppose, a legitimate cinematic equivalent of the way one automatically supplements reality with fantasy in conscious experience."Canby assessed fairly: "The autobiographical film form is ambitious and offers lots of opportunities for fancy effects that try to tell us we're watching captured reality. There are blackouts, when the sound is on and the camera is not; 'whiteouts,' and representations of film leaders, when the camera seems to be running out of film; 'flash frames,' or subliminal shots, when Joe flicks the camera on and off. From time to time, Joe also talks to the camera, but his musings on reality ('All I wanted to do was see, to encounter myself in the midst of my being ...') are as open-ended as the sight of an image receding into the infinity provided by two mirrors.

"Instead, Coming Apart compels attention as an anthology of various types of sexual endeavor, all photographed from the fixed position that in stag films is a matter of economic necessity (each new camera set-up adds more money to the budget) but here is a matter of conscious style." In fact, Canby suggested, "Coming Apart is an unequivocably entertaining movie only if you cherish the rigorous ceremonies enacted by participants in stag movies, photographed with the kind of frontal, skin-blemished candor that shrivels all desire. As an attempt to elevate pornography (or what we thought was pornography until all the points of reference came unstuck) into art, it is often witty and funny but it fails for several reasons, including Ginsberg's self-imposed limitations on form (to which he's not completely faithful)."

Locally, when Coming Apart had a one-week revival run at the Lumiere 10 years ago, Edward Guthmann from the San Francisco Chronicle complained: "The claustrophobic intimacy of Coming Apart is supposed to bring us inside Joe's head to share his agony and self-loathing, one supposes. Instead, the whole set-up of the hidden camera and the mirror—and the implied correlation between psychiatry and voyeurism—feels like a gimmick, an arty pose." (Time likewise criticized that Ginsberg's manifest intent to make his film "a set of X rays" comes off instead as "only a suite of poses.") Guthmann, further contextualizing that 1969 was the year of such films as Easy Rider, Medium Cool and Midnight Cowboy, suggested that—though cultural forms and sexual behavior were being turned inside out and Coming Apart probably had some relevance for some people—"today it looks phony and self-important. It's meant to be unvarnished and truthful but the situation it portrays—of Torn lying back while a series of desperate women throw themselves at him—is pure fantasy, the silly wish fulfillment of a Playboy subscriber."

Locally, when Coming Apart had a one-week revival run at the Lumiere 10 years ago, Edward Guthmann from the San Francisco Chronicle complained: "The claustrophobic intimacy of Coming Apart is supposed to bring us inside Joe's head to share his agony and self-loathing, one supposes. Instead, the whole set-up of the hidden camera and the mirror—and the implied correlation between psychiatry and voyeurism—feels like a gimmick, an arty pose." (Time likewise criticized that Ginsberg's manifest intent to make his film "a set of X rays" comes off instead as "only a suite of poses.") Guthmann, further contextualizing that 1969 was the year of such films as Easy Rider, Medium Cool and Midnight Cowboy, suggested that—though cultural forms and sexual behavior were being turned inside out and Coming Apart probably had some relevance for some people—"today it looks phony and self-important. It's meant to be unvarnished and truthful but the situation it portrays—of Torn lying back while a series of desperate women throw themselves at him—is pure fantasy, the silly wish fulfillment of a Playboy subscriber."Meanwhile at The Examiner, Wesley Morris added: "Bizarre, irritating, self-indulgent to the point of narcissism, Coming Apart is a stark, necessary reminder of what kind of actor Torn was when the nature of the work he was doing allowed him to fold a psyche into his particular brand of menace."

More recent critics have found much to recommend the film, though acknowledging it remains very much a product of its time. IndieWIRE crowns it "One of the most challenging, visionary, important films of independent cinema." At A.V. Club Nathan Rabin observes: "Coming Apart's secret-camera gimmick proves tremendously limiting, but it's also an audacious stylistic choice that lends the film a harrowing, claustrophobic intensity that can be almost unbearable." He concludes the film is "disconcertingly original, if self-indulgent and formless. A noble, if not entirely successful, experiment that promises more than it can deliver, it's a fascinating, frustrating time capsule that too often lapses into tedium."

More recent critics have found much to recommend the film, though acknowledging it remains very much a product of its time. IndieWIRE crowns it "One of the most challenging, visionary, important films of independent cinema." At A.V. Club Nathan Rabin observes: "Coming Apart's secret-camera gimmick proves tremendously limiting, but it's also an audacious stylistic choice that lends the film a harrowing, claustrophobic intensity that can be almost unbearable." He concludes the film is "disconcertingly original, if self-indulgent and formless. A noble, if not entirely successful, experiment that promises more than it can deliver, it's a fascinating, frustrating time capsule that too often lapses into tedium."PFA's "Eccentric Cinema: Overlooked Oddities and Ecstasies, 1963–82" continues this evening with a new print of L.Q. Jones' A Boy and His Dog (1975).

Cross-published on Twitch.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

ARGENTINE CINEMA—Lucrecia Martel on La Ciénaga

In yet another masterful programming coup, Joel Shepard scores one for the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts with—not only the Bay Area premiere of Lucrecia Martel's latest film The Headless Woman—but a retrospective of her earlier films La Ciénaga and Holy Girl with Martel present at both La Ciénaga (in conversation with her audience) and The Headless Woman (in conversation with B. Ruby Rich). Both evenings of her on-stage appearances sold out in advance and—judging by last night's enthused audience for La Ciénaga—her Bay Area appearance marks a singularly-anticipated event for a veritable who's who of San Franciscan cinephiles. This is one of those in-cinema experiences buttressed by its social texture in which I am delighted to have taken part.

In yet another masterful programming coup, Joel Shepard scores one for the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts with—not only the Bay Area premiere of Lucrecia Martel's latest film The Headless Woman—but a retrospective of her earlier films La Ciénaga and Holy Girl with Martel present at both La Ciénaga (in conversation with her audience) and The Headless Woman (in conversation with B. Ruby Rich). Both evenings of her on-stage appearances sold out in advance and—judging by last night's enthused audience for La Ciénaga—her Bay Area appearance marks a singularly-anticipated event for a veritable who's who of San Franciscan cinephiles. This is one of those in-cinema experiences buttressed by its social texture in which I am delighted to have taken part. After confessing he has seen La Ciénaga four times and aware that Martel based the story on memories of her own family, Joel Shepard kicked off the questioning by enquiring what Martel's family thought of her highly personal debut feature?

After confessing he has seen La Ciénaga four times and aware that Martel based the story on memories of her own family, Joel Shepard kicked off the questioning by enquiring what Martel's family thought of her highly personal debut feature?"There are several versions," Martel quipped. Before the film was finished, Martel showed her brothers a VHS version. They reacted that no one would understand the film because it was more like a home video of their family. Her great uncle—on whom she based the character of Gregorio (Martín Adjemián), husband to Mecha (Graciela Borges)—claimed not to understand anything in the film, to which his wife objected, "What do you mean you don't understand anything? You're just like Gregorio." Although the character was based on her great uncle—who Adjemián never met—her great uncle's wife recognized her husband in the actor's performance. As for her mother, she thinks Martel is the best director in the world.

Noting that each of her films contain complex—sometimes overwhelming—sound designs, Shepard wondered if Martel thought of the visuals and the sound separately when developing a film?

With La Ciénaga, Martel wasn't quite sure what her system would be since she'd not had much experience making cinema. Having never attended film school, she had no awareness of a working method. Martel qualified that she did achieve some schooling but wasn't able to carry through due to problems Argentina was facing at the time. That being said, when she conceives a film, sound precedes image. She based her dialogue on the oral sounds of family life; overheard phrases that are second nature to her. The sound design is thus already composed by the time she goes to the set to shoot the film. Although she doesn't know exactly how she's going to film things, the sound is already set.

With La Ciénaga, Martel wasn't quite sure what her system would be since she'd not had much experience making cinema. Having never attended film school, she had no awareness of a working method. Martel qualified that she did achieve some schooling but wasn't able to carry through due to problems Argentina was facing at the time. That being said, when she conceives a film, sound precedes image. She based her dialogue on the oral sounds of family life; overheard phrases that are second nature to her. The sound design is thus already composed by the time she goes to the set to shoot the film. Although she doesn't know exactly how she's going to film things, the sound is already set. Shepard suggested that repeated viewings of La Ciénaga have revealed its frequent comedy: Mecha is such a bizarre personality while Gregorio's personality is defined by how he dyes his hair. Tali (Mercedes Morán) becomes humorously obsessed with traveling to Bolivia. Not sure whether he was reading comedy into the film, he asked if Martel intended it?

Shepard suggested that repeated viewings of La Ciénaga have revealed its frequent comedy: Mecha is such a bizarre personality while Gregorio's personality is defined by how he dyes his hair. Tali (Mercedes Morán) becomes humorously obsessed with traveling to Bolivia. Not sure whether he was reading comedy into the film, he asked if Martel intended it?Her family laughs a great deal when they watch the film, Martel replied, but she suspects the film's humor is provincial, and not necessarily funny to everyone.

Shepard shared some reviews he found of La Ciénaga that amused him for being obtuse. Entertainment Weekly claimed La Ciénaga "had too much integrity for its own good" and, elsewhere, one critic complained that Martel was asking way too much of her audience. Which led him to consider the larger issue of Martel's relationship to her audiences and if she thought about them while making her films?

Shepard shared some reviews he found of La Ciénaga that amused him for being obtuse. Entertainment Weekly claimed La Ciénaga "had too much integrity for its own good" and, elsewhere, one critic complained that Martel was asking way too much of her audience. Which led him to consider the larger issue of Martel's relationship to her audiences and if she thought about them while making her films?Audiences are the only reason a filmmaker makes cinema, Martel insisted. However, you are born alone and you die alone in your own body. Love, conversation, language, sex: they're all attempts in some way to overcome so much loneliness. Cinema is a great opportunity—a possibility—for the viewer to immerse himself into the loneliness of the filmmaker's body in order to share it. Of course, it often happens that a viewer leaves a film without that happening; but, the intention is to have that happen. When that connection does happen, it's incredibly glorious. Sometimes that experience is a matter of seconds, and not the whole time of a film, which Martel has discovered through the comments made by her audiences where the point of relation is not inherent in the film itself, but the way the film reminds them of experiences they have had in their own lives.

As for the comment that she asks way too much of the viewer, Martel can accept the criticism, even as she understands that the viewer is sometimes prepared, sometimes not prepared for a demanding cinematic experience. Whether or not a viewer connects with her film has nothing to do with whether the film claims too much importance, or whether one viewer is more intelligent than another, or more interested in the film. The cinematic experience—favorable or disfavorable—is composed of mere moments.

As for the comment that she asks way too much of the viewer, Martel can accept the criticism, even as she understands that the viewer is sometimes prepared, sometimes not prepared for a demanding cinematic experience. Whether or not a viewer connects with her film has nothing to do with whether the film claims too much importance, or whether one viewer is more intelligent than another, or more interested in the film. The cinematic experience—favorable or disfavorable—is composed of mere moments.Asked whether it was difficult to get La Ciénaga financed and produced, Martel admitted to extreme luck because Argentine producer Lita Stantic advised her to send the film to Sundance, which she did, and where she won the prize for best screenplay. This helped secure funding to complete the project. What was strange about Sundance was that they encouraged her to change the ending of her screenplay because—from the point of view of the jury—they saw the film as being about alcoholics and alcoholism. They suggested that the accident Mecha had at the very beginning should be at the end. Martel countered, "Well, maybe. But since the film is not about alcoholism, that's just the way it is."

Initially in 1997 she tried to finance the film with money from within Salta, the northwestern province of Argentina where she's from. She spent a lot of time in the city of Salta, capital of the province, trying to make arrangements with the bank and convincing investors to finance the film. In the meantime, she was also trying to do some casting in a garage that was close to her house. She interviewed people of all ages from 9:00 in the morning to 9:00 at night. She taped these interviews. As it turned out, the experience was extraordinary for her. The people she cast from those interviews in 1997 then took part when the film was shot in 1999. That's why she offered them thanks for their patience in the film's closing credits.

Initially in 1997 she tried to finance the film with money from within Salta, the northwestern province of Argentina where she's from. She spent a lot of time in the city of Salta, capital of the province, trying to make arrangements with the bank and convincing investors to finance the film. In the meantime, she was also trying to do some casting in a garage that was close to her house. She interviewed people of all ages from 9:00 in the morning to 9:00 at night. She taped these interviews. As it turned out, the experience was extraordinary for her. The people she cast from those interviews in 1997 then took part when the film was shot in 1999. That's why she offered them thanks for their patience in the film's closing credits.Respectful that Martel's script for La Ciénaga won the prize at Sundance, one fellow wondered how closely that script matched the final film? Especially with regard to the seemingly improvised performances of the children? On a related note, he wondered how Martel cast the children and how she worked with them to achieve such natural performances?

Martel assured the young man that the film looks a lot like the screenplay except for a few scenes that she had to cut out for budgetary reasons and length. As for her system with working with actors, Martel doesn't have one, claiming every actor is different. She can't have a single system to talk to such different people. But when working with actors, and especially children, she tries not to change the written lines. She leaves them alone and avoids improvisation because the writing itself is a complex process and a difficult balancing act so—to begin improvising on the script—would change the film too much. However, because some child actors are truly monsters, she doesn't show them the written lines. She tells them what to say. If she shows them the written lines, some child actors try too hard to memorize them and lose the natural quality in their acting. She talks to them about things that look and sound like the written words but avoids showing them the literal script.

Martel assured the young man that the film looks a lot like the screenplay except for a few scenes that she had to cut out for budgetary reasons and length. As for her system with working with actors, Martel doesn't have one, claiming every actor is different. She can't have a single system to talk to such different people. But when working with actors, and especially children, she tries not to change the written lines. She leaves them alone and avoids improvisation because the writing itself is a complex process and a difficult balancing act so—to begin improvising on the script—would change the film too much. However, because some child actors are truly monsters, she doesn't show them the written lines. She tells them what to say. If she shows them the written lines, some child actors try too hard to memorize them and lose the natural quality in their acting. She talks to them about things that look and sound like the written words but avoids showing them the literal script.It's a curious thing, Martel added, when you're trying to work with actors to film a scene and it doesn't come off natural. She realized that—if you're really paying attention to the graphic pauses in the text and how it relates to what's happening in the scene—the graphic pauses reproduce almost identically. So it's the use of the air in these pauses, the use of the space, that will achieve a natural effect. Actors are often not trained, however, to do that. It's especially difficult with children.

When she sought to cast the children, she tried different things to help them concentrate. There is a serious problem that develops between the time you write a script and when you go to cast it and then when you finally go to film it. The boy she cast for the role of the little boy had grown into a big boy by the time she got to filming. The secret to working with children and non-actors is to have a good relationship from the time you're casting. Casting, first of all, is not to try to find out talent—which many directors think is the case; they believe the actor has to do something—but rather, casting is more an opportunity to find out what you dare ask of somebody and what you're really trying to accomplish. Casting determines your own limitations as a director, whether you are prudish or courageous in what you ask of your actors.

When she sought to cast the children, she tried different things to help them concentrate. There is a serious problem that develops between the time you write a script and when you go to cast it and then when you finally go to film it. The boy she cast for the role of the little boy had grown into a big boy by the time she got to filming. The secret to working with children and non-actors is to have a good relationship from the time you're casting. Casting, first of all, is not to try to find out talent—which many directors think is the case; they believe the actor has to do something—but rather, casting is more an opportunity to find out what you dare ask of somebody and what you're really trying to accomplish. Casting determines your own limitations as a director, whether you are prudish or courageous in what you ask of your actors.As for images of children in film, Martel stressed that the word that ruins the image of a child is the whole idea of "innocence." Innocence doesn't mean anything. The idea of a child's innocence is an invention by adults to withstand the fact that a child has his own life, and often his own sexuality. Whenever Martel writes, she thinks about the fact that there is a mystery or a secret that she's not aware of. That's why in her films you only see fragments. She doesn't attempt to create psychological characters because then viewers start getting caught up in those ideas of innocence and purity.

Martel was asked if she performed her own cinematography? She replied that, of course, she framed the shots but the actual camera work was done by the extraordinary director of photography Hugo Colace.

Martel was asked if she performed her own cinematography? She replied that, of course, she framed the shots but the actual camera work was done by the extraordinary director of photography Hugo Colace.The narrative traction of La Ciénaga is unique for not depending upon standard resolution. Notwithstanding its irresolute aesthetic, the movie compellingly moves forward. One young man wanted to know how Martel accomplished that?

La Ciénaga, Martel explained, as well as her other two films are based on a traditional oral structure. Conversation is a perfect example and, specifically, a conversation with her mother. After 40 minutes of talking on the phone—in which she and her mother discuss everything—Martel still doesn't know what her mother is trying to tell her. But when the conversation is over and Martel asks herself what it was about, she comes to a gradual understanding of how all that has been said ties together. Though she loves this way of working, it is—of course—problematic when it comes to marketing a film because audiences like to have tidy resolutions to their films. Then they would be able to recommend the film to their friends. Often, she has had viewers admit after seeing one of her films that they didn't really like it only to have them advise a few weeks later that—after sitting with the film—they really liked it; but, by then, the film is out of the theaters so they can't recommend it to their friends. The structure of oral narrative is something we are all trained to do by the nature of sustaining a conversation. We all know how to keep each other talking in conversations that don't have a beginning, middle or end.

La Ciénaga, Martel explained, as well as her other two films are based on a traditional oral structure. Conversation is a perfect example and, specifically, a conversation with her mother. After 40 minutes of talking on the phone—in which she and her mother discuss everything—Martel still doesn't know what her mother is trying to tell her. But when the conversation is over and Martel asks herself what it was about, she comes to a gradual understanding of how all that has been said ties together. Though she loves this way of working, it is—of course—problematic when it comes to marketing a film because audiences like to have tidy resolutions to their films. Then they would be able to recommend the film to their friends. Often, she has had viewers admit after seeing one of her films that they didn't really like it only to have them advise a few weeks later that—after sitting with the film—they really liked it; but, by then, the film is out of the theaters so they can't recommend it to their friends. The structure of oral narrative is something we are all trained to do by the nature of sustaining a conversation. We all know how to keep each other talking in conversations that don't have a beginning, middle or end. Curious about the presiding meaning of La Ciénaga, one fellow wondered if it had to do with Martel's previous statement about being born alone and dying alone and that existential wrestle with life? He wondered what world view she was trying to get across?

Curious about the presiding meaning of La Ciénaga, one fellow wondered if it had to do with Martel's previous statement about being born alone and dying alone and that existential wrestle with life? He wondered what world view she was trying to get across?Martel explained that, for her, La Ciénaga is a film about abandonment; a human being abandoned by divinity, by God if you will. She conceded this was wholly a personal point of view. A lot of people who have seen the film think it is about decadence; whereas for Martel, decadence is what gives her the most hope in this world. Anyway, the happiest parts of the film are about decadence.

Questioned about the sensual relationships between José (Juan Cruz Bordeu) and his cousins, and whether this denotes an ease in Argentine familial relations where siblings are more relaxed with each others' nudity, Martel joked that, unfortunately, when we think about Latinos, we think about Jennifer Lopez and reggaeton. That's the fantasy of the Latin body that satisfies gringo desire. As far as Martel is concerned, desire within a family is something that circulates, rather than being concentrated or personified in any single individual, object or action. Martel qualified that—with concern to this topic—she prefers not to say everything she thinks because she knows that a lot of people have lived through heartbreaking situations in such environments. Yet it seems to her that desire always overflows and goes beyond the norm. In other environments we have words to articulate concepts of desire; but, it's complicated within the family environment.

Questioned about the sensual relationships between José (Juan Cruz Bordeu) and his cousins, and whether this denotes an ease in Argentine familial relations where siblings are more relaxed with each others' nudity, Martel joked that, unfortunately, when we think about Latinos, we think about Jennifer Lopez and reggaeton. That's the fantasy of the Latin body that satisfies gringo desire. As far as Martel is concerned, desire within a family is something that circulates, rather than being concentrated or personified in any single individual, object or action. Martel qualified that—with concern to this topic—she prefers not to say everything she thinks because she knows that a lot of people have lived through heartbreaking situations in such environments. Yet it seems to her that desire always overflows and goes beyond the norm. In other environments we have words to articulate concepts of desire; but, it's complicated within the family environment.Intrigued by Martel's earlier statement that she approaches her filmmaking as if there is a mystery or a secret that she's unaware of, I ventured that the image of the steer stuck in the film's titular swamp likewise holds some kind of profound secret for me, especially because the children are obsessed with tormenting it in its misery. If, as she stated earlier, La Ciénaga is about the abandonment of divinity, I wondered if she was saying that—absent that divine impulse—humans are more susceptible to inherited notions of classism, racism and sexism, which the film observes unflinchingly? Do we get stuck in a place where—without inner wisdom—we rely on received and faulty knowledge?

Martel graciously offered that—when she writes—she tries to stay as far away from deliberate metaphors and symbols as possible; but, she understands that the need to create metaphors and symbols is a human way of amusing ourselves. She honestly—at least not consciously—didn't conceive of the steer stuck in the swamp as a metaphor for stagnation. With regard to abandonment by the divine, La Ciénaga ends before it becomes explicit that the only means of salvation is within and among ourselves. She understands that the viewer can relate this to the animal stuck in the swamp, but this was nothing she endeavored consciously or intentionally.

As for her next project, Martel has been writing an adaptation of a famous Argentine comic book regarding an alien invasion; but—since she doesn't know what's going to happen with that project—she's gone back to another topic, related to The Headless Woman, also within the fantastic genre. It's likewise about an alien invasion but the aliens are unknown relatives who invasively visit.

As for her next project, Martel has been writing an adaptation of a famous Argentine comic book regarding an alien invasion; but—since she doesn't know what's going to happen with that project—she's gone back to another topic, related to The Headless Woman, also within the fantastic genre. It's likewise about an alien invasion but the aliens are unknown relatives who invasively visit.Cross-published on Twitch.

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

SFSFF09—Underworld (1927) Introductory Remarks

I first caught Josef von Sternberg's Underworld (1927) at the Pacific Film Archive von Sternberg retrospective earlier this year accompanied by Judith Rosenberg on piano. I welcomed the opportunity to watch the film again projected on the Castro's giant screen with live piano accompaniment by the indefatigable Stephen Horne for the specific intent of savoring the scene where "Feathers" McCoy (Evelyn Brent) first comes to the attention of "Rolls Royce" Wensel (Clive Brook); namely, by way of an ostrich feather shaken loose from McCoy's outfit, drifting down to Wensel who is sweeping the floor below. Entrances are rarely so insinuating.

I first caught Josef von Sternberg's Underworld (1927) at the Pacific Film Archive von Sternberg retrospective earlier this year accompanied by Judith Rosenberg on piano. I welcomed the opportunity to watch the film again projected on the Castro's giant screen with live piano accompaniment by the indefatigable Stephen Horne for the specific intent of savoring the scene where "Feathers" McCoy (Evelyn Brent) first comes to the attention of "Rolls Royce" Wensel (Clive Brook); namely, by way of an ostrich feather shaken loose from McCoy's outfit, drifting down to Wensel who is sweeping the floor below. Entrances are rarely so insinuating. Eddie Muller, the "Czar of Noir", had the honors of introducing Underworld to its SFSFF audience. Often asked—in his capacity as the Czar—what he considers to be the first film noir, Muller admitted he rarely answers the question because he considers trying to pin down the first film noir as somewhat an absurd endeavor. Notwithstanding, an ever-expanding roster of scholars continue to sift through pre-1940 films in search of some sort of cinematic missing link to establish a proto-noir precedent. "Here's the deal," Muller punched, "to me, film noir applies to an organic, artistic movement within the business of popular entertainment and it has been more than sufficiently proven that its Hollywood incarnation began in the early 1940s, primarily with two films: the A-list The Maltese Falcon (1941) and a far-less influential—but not insignificant—64-minute B-film called Stranger On the Third Floor made by RKO in 1940." The Maltese Falcon, based on Dashiell Hammett's famous '30s novel popularized the figure of the wisecracking anti-hero up to his ears in an amoral world of greed and avarice. Stranger On the Third Floor introduced to small-scale Hollywood-made crime stories an extravagant expressionism in art direction and cinematography. Both these films, however, are mere touchstones, the progenitors if you will, the exemplars of noir's content and style. The definitive film noir Double Indemnity would not be released until three years later in 1944.

Eddie Muller, the "Czar of Noir", had the honors of introducing Underworld to its SFSFF audience. Often asked—in his capacity as the Czar—what he considers to be the first film noir, Muller admitted he rarely answers the question because he considers trying to pin down the first film noir as somewhat an absurd endeavor. Notwithstanding, an ever-expanding roster of scholars continue to sift through pre-1940 films in search of some sort of cinematic missing link to establish a proto-noir precedent. "Here's the deal," Muller punched, "to me, film noir applies to an organic, artistic movement within the business of popular entertainment and it has been more than sufficiently proven that its Hollywood incarnation began in the early 1940s, primarily with two films: the A-list The Maltese Falcon (1941) and a far-less influential—but not insignificant—64-minute B-film called Stranger On the Third Floor made by RKO in 1940." The Maltese Falcon, based on Dashiell Hammett's famous '30s novel popularized the figure of the wisecracking anti-hero up to his ears in an amoral world of greed and avarice. Stranger On the Third Floor introduced to small-scale Hollywood-made crime stories an extravagant expressionism in art direction and cinematography. Both these films, however, are mere touchstones, the progenitors if you will, the exemplars of noir's content and style. The definitive film noir Double Indemnity would not be released until three years later in 1944. "Having said that," Muller qualified, "I have found—as a person interested in film preservation and film history—that it is great fun and it is invaluable to spur interest in older films by searching for film noir's antecedents. That's why I am here today and happy to introduce 1927's Underworld as a co-presentation of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and the Film Noir Foundation. Not that I actually believe that Underworld is truly a film noir. It is a gangster picture and it is one of the first of its kind. Some people would argue that 1912's The Muskateers Of Pig Alley by D.W. Griffith or a film in 1915 called Regeneration directed by Raoul Walsh might be the first true depiction of gansters on the movie screen. Be that as it may, I think Underworld is the first example of what society would come to identify as the gangster picture." Structurally, dynamically, and visually, Underworld possesses the elements that have led to the creation of the recently-released Public Enemies. The game hasn't really changed all that much. Honestly speaking, Muller considers such silent films as Sunrise or A Cottage on Dartmour to be "much more noir."

"Having said that," Muller qualified, "I have found—as a person interested in film preservation and film history—that it is great fun and it is invaluable to spur interest in older films by searching for film noir's antecedents. That's why I am here today and happy to introduce 1927's Underworld as a co-presentation of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and the Film Noir Foundation. Not that I actually believe that Underworld is truly a film noir. It is a gangster picture and it is one of the first of its kind. Some people would argue that 1912's The Muskateers Of Pig Alley by D.W. Griffith or a film in 1915 called Regeneration directed by Raoul Walsh might be the first true depiction of gansters on the movie screen. Be that as it may, I think Underworld is the first example of what society would come to identify as the gangster picture." Structurally, dynamically, and visually, Underworld possesses the elements that have led to the creation of the recently-released Public Enemies. The game hasn't really changed all that much. Honestly speaking, Muller considers such silent films as Sunrise or A Cottage on Dartmour to be "much more noir." Offering backstory on Underworld in order to provide insight into the moviemaking process and some of the practical and pertinent clues to the roots of film noir, Muller observed that most film historians—especially those enamored with the auteur theory—consider Underworld to be a Josef von Sternberg film. It was the director's third assignment but the first produced with the full support of a major studio, namely Paramount. Underworld was also the first film to display many of the visual flourishes that became Josef von Sternberg's signature. Of even greater historical significance to Muller, however, was that Underworld was the first story credit for Ben Hecht, who would go on to become one of the most prolific and respected screenwriters of Hollywood history, if not the most prolific and respected screenwriter of Hollywood history.

Offering backstory on Underworld in order to provide insight into the moviemaking process and some of the practical and pertinent clues to the roots of film noir, Muller observed that most film historians—especially those enamored with the auteur theory—consider Underworld to be a Josef von Sternberg film. It was the director's third assignment but the first produced with the full support of a major studio, namely Paramount. Underworld was also the first film to display many of the visual flourishes that became Josef von Sternberg's signature. Of even greater historical significance to Muller, however, was that Underworld was the first story credit for Ben Hecht, who would go on to become one of the most prolific and respected screenwriters of Hollywood history, if not the most prolific and respected screenwriter of Hollywood history. Hecht came to Hollywood in 1925 at the behest of his colleague Herman Mankiewicz (screenwriter for Citizen Kane) who, like Hecht, was a newspaper reporter with literary ambitions. "Mankie"—as he was known—extended an invitation to Ben Hecht in a telegram, which famously included: "Millions are to be made out here and your only competition is idiots. Don't let it get around." Once ensconced in an office at Paramount earning $300 a week, Hecht got a crash course in picture writing from his sarcastic pal. "I wanted to point out to you," Mankiewicz advised, "that in a novel a hero can lay 10 girls and marry the virgin for the finish. In a movie, this is not allowed. The hero, as well as the heroine, have to be virgins. The villain can lay anybody he wants, have as much fun as he wants cheating and stealing, getting rich, and whipping the servants; but, you have to shoot him in the end and—when he falls with a bullet in his forehead—it is advisable that he clutch the Gobelins tapestry on the library wall and bring it down over his head as sort of a symbolic shroud. Also, covered by such a tapestry, the actor does not have to hold his breath while he is being photographed as the dead man." Ben Hecht had an immediate reaction to this advice. To quote: "The thing to do was to skip the heroes and heroines and to write a movie that contained only villains and broads. That way I do not have to tell any lies."

Hecht came to Hollywood in 1925 at the behest of his colleague Herman Mankiewicz (screenwriter for Citizen Kane) who, like Hecht, was a newspaper reporter with literary ambitions. "Mankie"—as he was known—extended an invitation to Ben Hecht in a telegram, which famously included: "Millions are to be made out here and your only competition is idiots. Don't let it get around." Once ensconced in an office at Paramount earning $300 a week, Hecht got a crash course in picture writing from his sarcastic pal. "I wanted to point out to you," Mankiewicz advised, "that in a novel a hero can lay 10 girls and marry the virgin for the finish. In a movie, this is not allowed. The hero, as well as the heroine, have to be virgins. The villain can lay anybody he wants, have as much fun as he wants cheating and stealing, getting rich, and whipping the servants; but, you have to shoot him in the end and—when he falls with a bullet in his forehead—it is advisable that he clutch the Gobelins tapestry on the library wall and bring it down over his head as sort of a symbolic shroud. Also, covered by such a tapestry, the actor does not have to hold his breath while he is being photographed as the dead man." Ben Hecht had an immediate reaction to this advice. To quote: "The thing to do was to skip the heroes and heroines and to write a movie that contained only villains and broads. That way I do not have to tell any lies." In his 1954 autobiography, A Child of the Century, Hecht explained that, "As a newspaper man I have learned that nice people—the audience—loved criminals, and doted on reading about their love problems as well as their sadism. My movie, grounded on this simple truth, was produced under the title Underworld. It was the first gangster movie to bedazzle the movie fans and there were no lies in it, except for a half dozen sentimental flourishes introduced by its director Joe von Sternberg." Hecht thought so little of von Sternberg's additions that—upon seeing the film—he sent the director a very blunt note via telegram: "You poor ham. Take my name off the picture." Paramount kept Hecht's name on the film and Underworld ended up being nominated for and winning the very first Oscar® ever presented for Best Original Story. Hecht would win again in that category in 1935 for a film called The Scoundrel.

In his 1954 autobiography, A Child of the Century, Hecht explained that, "As a newspaper man I have learned that nice people—the audience—loved criminals, and doted on reading about their love problems as well as their sadism. My movie, grounded on this simple truth, was produced under the title Underworld. It was the first gangster movie to bedazzle the movie fans and there were no lies in it, except for a half dozen sentimental flourishes introduced by its director Joe von Sternberg." Hecht thought so little of von Sternberg's additions that—upon seeing the film—he sent the director a very blunt note via telegram: "You poor ham. Take my name off the picture." Paramount kept Hecht's name on the film and Underworld ended up being nominated for and winning the very first Oscar® ever presented for Best Original Story. Hecht would win again in that category in 1935 for a film called The Scoundrel. Several years later, Howard Hughes wanted Ben Hecht to write a movie based on the exploits of Al Capone. Hecht was a newspaper man in Chicago and knew the Capone territory very well. Hecht agreed to this with specific conditions. He had to be paid $1,000 per day in cash with the money delivered precisely at 6:00. "In that way," Hecht said, "I stood to lose only a single day's labor if Mr. Hughes turned out to be insolvent." He was not only a good writer, he was a smart businessman. The finished script of Scarface incorporated many elements that Hecht used in Underworld and also brought a pair of midnight visitors to his Hollywood hotel. Muller donned Hecht's persona to tell the tale.