"We wanted to change history, but destiny led us to this strange sensation of uncertainty and defeat. What did we do wrong? What mistakes did we make?"—Sergio Bitar, Dawson Island prisoner, and author of Isla 10.

"We wanted to change history, but destiny led us to this strange sensation of uncertainty and defeat. What did we do wrong? What mistakes did we make?"—Sergio Bitar, Dawson Island prisoner, and author of Isla 10."I felt like the protagonist of one of those World War II movies. When we arrived at the camp, some of us cried to see so many wire fences. There were 27. It was difficult to believe."—Baldovino Gomez, Dawson Island prisoner.

"A story starts when someone is born, someone dies, someone leaves, or someone arrives."—Director Miguel Littin, quoting Ernest Hemingway.

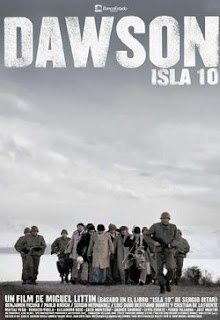

The arrival in September 1973 of approximately 50 former Chilean President Salvador Allende's Popular Unity ministers, senators and deputies to Dawson Island—a concentration camp "at the end of the world"; i.e., latitude 53 South at the western end of the Strait of Magellan—introduces a political crime largely unknown by the world, let alone most Chileños; a calculated historical omission that acclaimed Chilean filmmaker Miguel Littin sought to redress through his feature film Dawson Island, 10 (2009), which screened at PSIFF10 as Chile's official submission to the Best Foreign Language Film category of the Academy Awards®. Although Littin has been nominated twice for an Oscar®—first, as Mexico's official submission for Actas de Marusia (1975), and then again as Nicaragua's official submission for Alsino El Condor (1982)—Dawson Island, 10 marks the first time he has represented his native country. Although Dawson Island, 10 did not make the Oscar® shortlist, Littin advised me that he was pleased with the attention that the submission process afforded the film. The film is the first Chilean-Brazilian co-production and likewise represented Chile at Spain's Goya Awards.

The arrival in September 1973 of approximately 50 former Chilean President Salvador Allende's Popular Unity ministers, senators and deputies to Dawson Island—a concentration camp "at the end of the world"; i.e., latitude 53 South at the western end of the Strait of Magellan—introduces a political crime largely unknown by the world, let alone most Chileños; a calculated historical omission that acclaimed Chilean filmmaker Miguel Littin sought to redress through his feature film Dawson Island, 10 (2009), which screened at PSIFF10 as Chile's official submission to the Best Foreign Language Film category of the Academy Awards®. Although Littin has been nominated twice for an Oscar®—first, as Mexico's official submission for Actas de Marusia (1975), and then again as Nicaragua's official submission for Alsino El Condor (1982)—Dawson Island, 10 marks the first time he has represented his native country. Although Dawson Island, 10 did not make the Oscar® shortlist, Littin advised me that he was pleased with the attention that the submission process afforded the film. The film is the first Chilean-Brazilian co-production and likewise represented Chile at Spain's Goya Awards.However, as reported by Pascale Bonnefoy for The Global Post, some people—including former Dawson Island prisoner Miguel Lawner—have taken exception to how Littin's film "sometimes consciously sacrifices accuracy to dramatic license, offering viewers a trade-off: exposure to this period of history at the expense of the historical record." Lawner criticized: "The movie is full of situations that aren't like they actually happened. I went to see the movie very skeptical, but since then, I have gotten many calls, especially from young people, impacted by the movie, saying they had no idea all of that had happened. In that sense, I guess Littin achieved his objective, in spite of the liberties he took."

That such an impact should be but one of Littin's prime objectives in recounting the story of Dawson Island seems evident; but—as he has likewise forcefully asserted in a piece for Moving Pictures Magazine—"Making a film in Latin America and especially in Chile is not just a technical and economic challenge but is also a matter of confronting censorship that moves through shadows, hidden powers with the mission to keep these histories forgotten. That's why there is a permanent disqualification. Cinema must not be political, they say as they scare away and use the power of the media to quietly squelch whoever dares to tell the stories, and many filmmakers fall into their traps and enter the game. Cinema, an ontology that is born from life, projects it and, through emotion and truth, permeates the consciences of free men and women of this world. In their names and for them, I film."

That such an impact should be but one of Littin's prime objectives in recounting the story of Dawson Island seems evident; but—as he has likewise forcefully asserted in a piece for Moving Pictures Magazine—"Making a film in Latin America and especially in Chile is not just a technical and economic challenge but is also a matter of confronting censorship that moves through shadows, hidden powers with the mission to keep these histories forgotten. That's why there is a permanent disqualification. Cinema must not be political, they say as they scare away and use the power of the media to quietly squelch whoever dares to tell the stories, and many filmmakers fall into their traps and enter the game. Cinema, an ontology that is born from life, projects it and, through emotion and truth, permeates the consciences of free men and women of this world. In their names and for them, I film." Dawson Island, 10 is based on the book Isla 10 by Sergio Bitar, who in 1973 served as Minister of Mining under President Allende. Currently, Bitar is Minister of Public Works under President Michelle Bachelet. In addition, Bitar is part of the Executive Committee of the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, DC. Prior to these positions, he was a Senator and Chairman of the Party for Democracy (PPD), which forms part of the current government coalition in Chile since 1990. As indicated by Boyd van Hoeij at Variety—despite Bitar's assistance on the screenplay—Littin's adaptation relegates Bitar to "a bit player" in its narrative preference for a more general overview. But Littin has made it clear in his interview with Alt Film Guide "that the book and the film were two different bodies, but with the same soul."

Dawson Island, 10 is based on the book Isla 10 by Sergio Bitar, who in 1973 served as Minister of Mining under President Allende. Currently, Bitar is Minister of Public Works under President Michelle Bachelet. In addition, Bitar is part of the Executive Committee of the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, DC. Prior to these positions, he was a Senator and Chairman of the Party for Democracy (PPD), which forms part of the current government coalition in Chile since 1990. As indicated by Boyd van Hoeij at Variety—despite Bitar's assistance on the screenplay—Littin's adaptation relegates Bitar to "a bit player" in its narrative preference for a more general overview. But Littin has made it clear in his interview with Alt Film Guide "that the book and the film were two different bodies, but with the same soul."Miguel Littin was born in Palmilla, Colchagua, Chile, earned a Dramatic Art Degree from the Universidad de Chile, and has written and adapted a vast number of plays, including El Hombre de las Estrellas (The Man of the Stars). At the age of 25, he shot the film El Chacal de Nahueltoro (1968), which became one of the most successful films in Latin American cinematography and has since gone on to be recognized as a classic worldwide. Littin has been awarded many prizes and distinctions. The French Government bestowed upon him the official title of Caballero de Las Artes y Letras. In 2002, Littin was granted Mexico's most important official recognition: La Orden Aguila Azteca. As well as being a novelist, Miguel Littin has been the subject of Gabriel García Márquez's 1986 book Clandestine in Chile: Adventures of Miguel Littin.

My thanks to Cheri Warner, publicist at Weismann/Markovitz Communications, for inviting me to interview Miguel Littin and for patiently arranging same. Also, I'm grateful to Lilinas Mejiras, Assistant Trade Commissioner for Pro/Chile, for stepping in to offer interpretive assistance.

My thanks to Cheri Warner, publicist at Weismann/Markovitz Communications, for inviting me to interview Miguel Littin and for patiently arranging same. Also, I'm grateful to Lilinas Mejiras, Assistant Trade Commissioner for Pro/Chile, for stepping in to offer interpretive assistance.* * *

Michael Guillén: It was fascinating for me to watch this story because I knew nothing about Dawson Island. And—as you've stated in your director notes about the organization of memory: that memory is not restored, but awakened—Dawson Island, 10 awakened for me the memory of the shame I felt as an American citizen of the Nixon administration's involvement with Pinochet's overthrow of Allende. That made me wonder about how the Chilean public has responded to having their memories awakened about events in the not-too-distant past?

Miguel Littin: Extraordinarily well. All of the screenings were sold out. It was very satisfying for me to see the long lines waiting outside the theaters to get in to see the movie. And the audiences were composed of people from four different generations. The film caused different emotions: some people laughed; some people cried; some people experienced deep emotions. The film is still being screened in Chile.

Miguel Littin: Extraordinarily well. All of the screenings were sold out. It was very satisfying for me to see the long lines waiting outside the theaters to get in to see the movie. And the audiences were composed of people from four different generations. The film caused different emotions: some people laughed; some people cried; some people experienced deep emotions. The film is still being screened in Chile.Guillén: Clearly, the timing to tell the story of Dawson Island was just right?

Littin: Yes.

Guillén: I'm aware that you have adapted other literary works to film. This particular film was based upon Sergio Bitar's book and Bitar helped you to write the screenplay. What is the value for you as a filmmaker to work with existing literary works?

Littin: I am fascinated with literature in general. When I read a book, it's a pleasure to imagine a script. It's my passion. I remember when I adapted Alejo Carpentier's El recurso del método [The Recourse to the Method, 1978], I was writing the script in the margins of the pages. When I adapted Gabriel García Márquez's La Viuda de Montiel (1979), I spoke with García Márquez and he asked me how the script was going? I showed him two empty notebooks. "So where's the script?!" García Márquez asked. I told him, "It is in my mind. It's in my head." In that instance, I didn't take any notes to write the script. I have a fluid connection with literature and scriptwriting.

Littin: I am fascinated with literature in general. When I read a book, it's a pleasure to imagine a script. It's my passion. I remember when I adapted Alejo Carpentier's El recurso del método [The Recourse to the Method, 1978], I was writing the script in the margins of the pages. When I adapted Gabriel García Márquez's La Viuda de Montiel (1979), I spoke with García Márquez and he asked me how the script was going? I showed him two empty notebooks. "So where's the script?!" García Márquez asked. I told him, "It is in my mind. It's in my head." In that instance, I didn't take any notes to write the script. I have a fluid connection with literature and scriptwriting.Guillén: And also with poetry?

Littin: Yes.

Guillén: In this film, I appreciated the sequence where you shot the sea with the recitation of Pablo Neruda's poem. In watching a lot of Latin American cinema, I often see this connection between politics and poetry. Can you speak to that connection?

Guillén: In this film, I appreciated the sequence where you shot the sea with the recitation of Pablo Neruda's poem. In watching a lot of Latin American cinema, I often see this connection between politics and poetry. Can you speak to that connection?Littin: It has to do with identity. Latin America's identity has a lot to do with its poetry, much like Walt Whitman is associated with American democracy. Neruda, [César] Vallejo, and many others have provided a democratic identity for Latin America. Poetry is included in Latin America's history, in its memory, and expresses the Latin American fascination with the word. In his words in the poem read in that sequence, Neruda is linking nature—the sea, the mountains—such that they move forward to create an identity that also creates a history for Chile, from love poems to historic poems.

Guillén: Which leads me to consider how you have effectively used the image of the pencil as being equivalent to a weapon; self-expression as a weapon. Also, in the image of the inscribed stones. Did the prisoners at Dawson Island actually carve into stones? Or was that a poetic license inspired from Neruda's poem: "In every stone, I left a telegram written"?

Littin: No, that actually happened.

Guillén: Do these stones still exist?

Littin: When they premiered Dawson Island, 10 in Santiago, they had an exhibition of the carved stones.

Guillén: I would love to see those. Where are they now?

Littin: They're still in Santiago. The people who were collecting the stones loaned them by way of exhibition to the premiere of the movie.

[Note: As if to confirm the equivalency of self-expression with weaponry, José Tohá's testimony at the Chile Information Project relates: "The island produced 'an enormous feeling of isolation, of intense cold, wind, few sunny days. It was a prison, surrounded by water, with absolutely no escape. One of the great things was to be allowed to carve the stones: it relieved the stress and for some brought in some income.' Until one day an officer decided that the implements used were dangerous weapons and carving was banned."]

[Note: As if to confirm the equivalency of self-expression with weaponry, José Tohá's testimony at the Chile Information Project relates: "The island produced 'an enormous feeling of isolation, of intense cold, wind, few sunny days. It was a prison, surrounded by water, with absolutely no escape. One of the great things was to be allowed to carve the stones: it relieved the stress and for some brought in some income.' Until one day an officer decided that the implements used were dangerous weapons and carving was banned."]Guillén: Your conscious usage of the camera as a tool is pronounced throughout your work. In Dawson Island, 10, you shifted the palette frequently from black and white to color throughout the film. Why did you do that?

Littin: Well, it's like when you play poker and you show your hand. It's a way to get people involved in the game. I made a proposition at the beginning of the film that it was going to be this way or that way. Was it going to be like a documentary or a feature film? I mixed everything up—fiction, documentary—and used a narrative language combining both.

Guillén: So are you saying you were hedging bets to win the best audience?

Littin: I'm not sure about that. But I wanted to create a link between the audience and the movie.

Guillén: Why did you choose to combine authentic documentary footage with reenacted simulations made to look like documentary footage—specifically the scenes of Allende in the palace during the 1973 coup d'état? [Note: This was one of the scenes objected to by Miguel Lawner for suggesting that Allende was murdered, rather than the official recognition of his death by suicide.]

Guillén: Why did you choose to combine authentic documentary footage with reenacted simulations made to look like documentary footage—specifically the scenes of Allende in the palace during the 1973 coup d'état? [Note: This was one of the scenes objected to by Miguel Lawner for suggesting that Allende was murdered, rather than the official recognition of his death by suicide.]Littin: Because nothing of what happens in the movie would have happened without Allende. The history of Chile is marked and addressed by the presence of Allende. Allende was forefront in the memory of all the Dawson Island prisoners. It's similar to Hamlet: when he remembers his father, he can't live. The remembrance of Allende doesn't allow Chile to live quietly. Until all the wounds are healed, neither Denmark nor Chile will be quiet.

Guillén: As Dawson Island, 10 starts out, the characters are rendered fairly black or white. The audience knows straight off who the good guys are (the prisoners) and who the bad guys are (the guards). But, by film's end, that certainty has capsized. This created a compelling ambivalence for me. I didn't know what to feel towards certain of the characters, the director of the concentration camp (Sergio Hernández) for example, who—though harshly adherent to military protocol when the prisoners arrive—became recalcitrant with his later interpretations of that protocol, thereby actually saving the lives of the Dawson Island prisoners from military factions wishing them executed for expediency's sake. What were you trying to show in this ambivalent behavior?

Guillén: As Dawson Island, 10 starts out, the characters are rendered fairly black or white. The audience knows straight off who the good guys are (the prisoners) and who the bad guys are (the guards). But, by film's end, that certainty has capsized. This created a compelling ambivalence for me. I didn't know what to feel towards certain of the characters, the director of the concentration camp (Sergio Hernández) for example, who—though harshly adherent to military protocol when the prisoners arrive—became recalcitrant with his later interpretations of that protocol, thereby actually saving the lives of the Dawson Island prisoners from military factions wishing them executed for expediency's sake. What were you trying to show in this ambivalent behavior? Littin: That's it. That life is neither black nor white. There are greys inbetween. And the importance of that is that nothing is definite, one can change things, different outcomes can be achieved dependent upon oneself. Instead of only taking orders, the soldiers from the army were also able to impact results. In the end, it's about having faith in the human condition; having faith that the human condition is fragile but changeable. In some ways this example from Dawson Island tells soldiers in the military that they cannot behave this way again because they are also human beings who have feelings, not just soldiers. By dividing the army from the civilian populace, we're doing militarism a favor. When you promote individual responsibility, however, these problems become different. Besides, it was the true story. I didn't make it up. That's how it happened. That's how they behaved.

Littin: That's it. That life is neither black nor white. There are greys inbetween. And the importance of that is that nothing is definite, one can change things, different outcomes can be achieved dependent upon oneself. Instead of only taking orders, the soldiers from the army were also able to impact results. In the end, it's about having faith in the human condition; having faith that the human condition is fragile but changeable. In some ways this example from Dawson Island tells soldiers in the military that they cannot behave this way again because they are also human beings who have feelings, not just soldiers. By dividing the army from the civilian populace, we're doing militarism a favor. When you promote individual responsibility, however, these problems become different. Besides, it was the true story. I didn't make it up. That's how it happened. That's how they behaved. Guillén: It's a great honor for me to speak with you today because of the strength of your career and the evident influence you have had on so many younger Chilean filmmakers. I've spoken with many of them—Alicia Scherson, Pablo Larraín, Sebastián Campos—and I'm wondering if you have any final thoughts regarding Chile's younger filmmakers?

Guillén: It's a great honor for me to speak with you today because of the strength of your career and the evident influence you have had on so many younger Chilean filmmakers. I've spoken with many of them—Alicia Scherson, Pablo Larraín, Sebastián Campos—and I'm wondering if you have any final thoughts regarding Chile's younger filmmakers?Littin: I interact with them all the time. I admire their films.

Guillén: Among them, is there anyone you would single out to have me pay attention to?

Littin: There are several who are really good, including those you have mentioned. Sebastián Campos's Navidad is quite good. Also the work of Alejandro Fernández Almendras (Huacho). The work of Andrés Wood is very important. He's made some good films like Machuca (2004); but, I think he is accomplished and mature and will soon have a big hit.

But more important than specific recommendations is to remember that Chile's film industry possesses four generations of filmmakers currently making films. This continuity or lineage began in 1968 when a new wave of filmmaking in Chile was encouraged. This has generated more and more satisfying films out of Chile. All of these young filmmakers have their eye on the human being.

But more important than specific recommendations is to remember that Chile's film industry possesses four generations of filmmakers currently making films. This continuity or lineage began in 1968 when a new wave of filmmaking in Chile was encouraged. This has generated more and more satisfying films out of Chile. All of these young filmmakers have their eye on the human being.Cross-published on Twitch.