Linda Williams is Professor of Film Studies and Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. Her books include Screening Sex and Porn Studies, both also published by Duke University Press; Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson; Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film; and Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the "Frenzy of the Visible." In 2013, Williams received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Linda Williams' introduction to On The Wire is used with permission of Duke University Press. Purchase On The Wire by supporting your local bookstore, or buy the book through Amazon.com. My thanks to Laura Sell at Duke University Press for setting up my interview with Linda Williams.

* * *

Michael Guillén: In your introduction to On The Wire, you explain that you got into watching The Wire when you were laid up in bed in the summer and fall of 2007. How did you then go about structuring your study? Did you watch the series several times? How did you decide which episodes would best present your themes?

Linda Williams: It was harder than anything I'd ever done because we're talking about more than 60 hours of viewing time. I found that daunting. I simply watched The Wire the way anybody watches it, though I didn't watch it on a weekly basis—somebody had given me what were in effect bootleg copies of the first three seasons—so I was able to watch it every night and I did. It was the wonderful thing that I would give myself every night. I would go to bed at 7:00 and I would watch an hour of The Wire and then go to sleep exhausted.

It was overwhelming to me and also really intriguing: what was it that I had watched? What would I call it? A really long movie? That didn't quite seem right. I'd never encountered a serial that was as compelling. Serials never seemed timely to me, even though I'd grown up with serials like Flash Gordon.

My initial thought was, "Wow. What did I just see? That's amazing." Then I needed to teach an honors seminar with a relatively small class of only about 15 students so I could experiment, which is a rarity at a large public university. I said, "Well, all right, what if I were to teach a course on The Wire?" Then, as a group, the class and I could try to figure out what we were watching. But even there I had the problem of how to screen it? So, I would give long screening sessions every week of three to four hours; but, that still wasn't quite long enough to see it all. Besides which, I didn't want to just re-experience seeing it all over again—although, ultimately, that is what I did—but, I wanted to be able to organize it a little bit for students and help them through the viewing even though I was not really a great guide at that point because I didn't know much; I didn't know enough.

That first class that I taught was probably pretty bad. But one of the devices that I used in order to decide who would be in the class—because I couldn't take everyone who wanted to be in it—was to give them a quiz about the first season. I expected them to have seen the first season. The quiz had simple questions like "who was Omar?" or "what word do detectives Moreland and McNulty exchange in episode four of season one?" Questions like that. Then I could weed out people who didn't already care or hadn't already immersed themselves in the first season. I basically decided not to show the first season and expected the students to know it. I don't particularly like the second season, although I showed some highlights from it. Basically, then, I had three more seasons to show them. I felt a bit guilty about that. I kept changing my mind. At first, I was going to only give them flat summaries of certain things but then I realized they had to see more. I was bad at it because I didn't know how to handle a series that big and then, of course, there was the necessity of having to compare other kinds of serial television narratives. So the first time I taught The Wire, I learned a great deal from the students who were, most of them, real fans, if not absolutely brilliant analysts. They were really into it. They knew it and they had more familiarity with television than I did because I, frankly, had not watched much television.

Then the second time I taught it, I did it in a large lecture class and I had it down. I knew which episodes I wanted them to see and I would analyze them and talk about them. It was in that process of trying to organize what it was—it would actually be interesting for me to go back and look at the syllabus of that class—that I began to think about television seriality as an important thing to talk about. I began to think about the rhythm of a series like The Wire and to count the beats, which was important to me. Somewhere in the book I argue that there is a telling rhythm to television that is different from movies. That rhythm is created by commercials. And it's a rhythm that doesn't quite trust the attention span of viewers. Even in a series like The Wire, if you take the commercials out—the commercials often interrupt moments so you get a climax before a commercial—that is the rhythm of television. Even when the commercials aren't there, you can tell that they should be there; that they're meant to be there. So I started counting the beats and rhythmically figuring it out and then I thought, "Well, how did this come to be? How did David Simon come to write this?" That was a rather natural process of reading his newspaper writing and reading his long journalism. That became important. Gradually I began to get chapters.

Then for me there was this huge question that everybody who talks about The Wire talks about its authenticity, its realism, its quality of being a visual novel like the 19th century realist novel and I just felt that was wrong because of earlier work that I've done with melodrama. That became a major thesis of a couple of the chapters, which allowed me to explore the tragic elements of The Wire, which are definitely there, but then pursue the series' more melodramatic qualities. And I don't mean "melodramatic" as a pejorative term.

Guillén: No, in fact, you've given the term a resuscitated definition. I had envisioned that maybe in your office you set up a huge evidence board with lines connecting names and photos.

Williams: [Laughs.] No, no, no.

Guillén: I didn't quite know how a person could have culled out and connected such subtle themes from so many various episodes, so I thank you for all that associative research. Let's approach some of the terms you've used in your study. One of the terms that has intrigued me in recent years is the concept of the "spatial imaginary." I can't profess to understand it fully or that I have explored it fully—you've certainly inspired me to explore it more fully—but can you give my readers a sense of what is a spatial imaginary and how you have applied it as a racial perspective on The Wire?

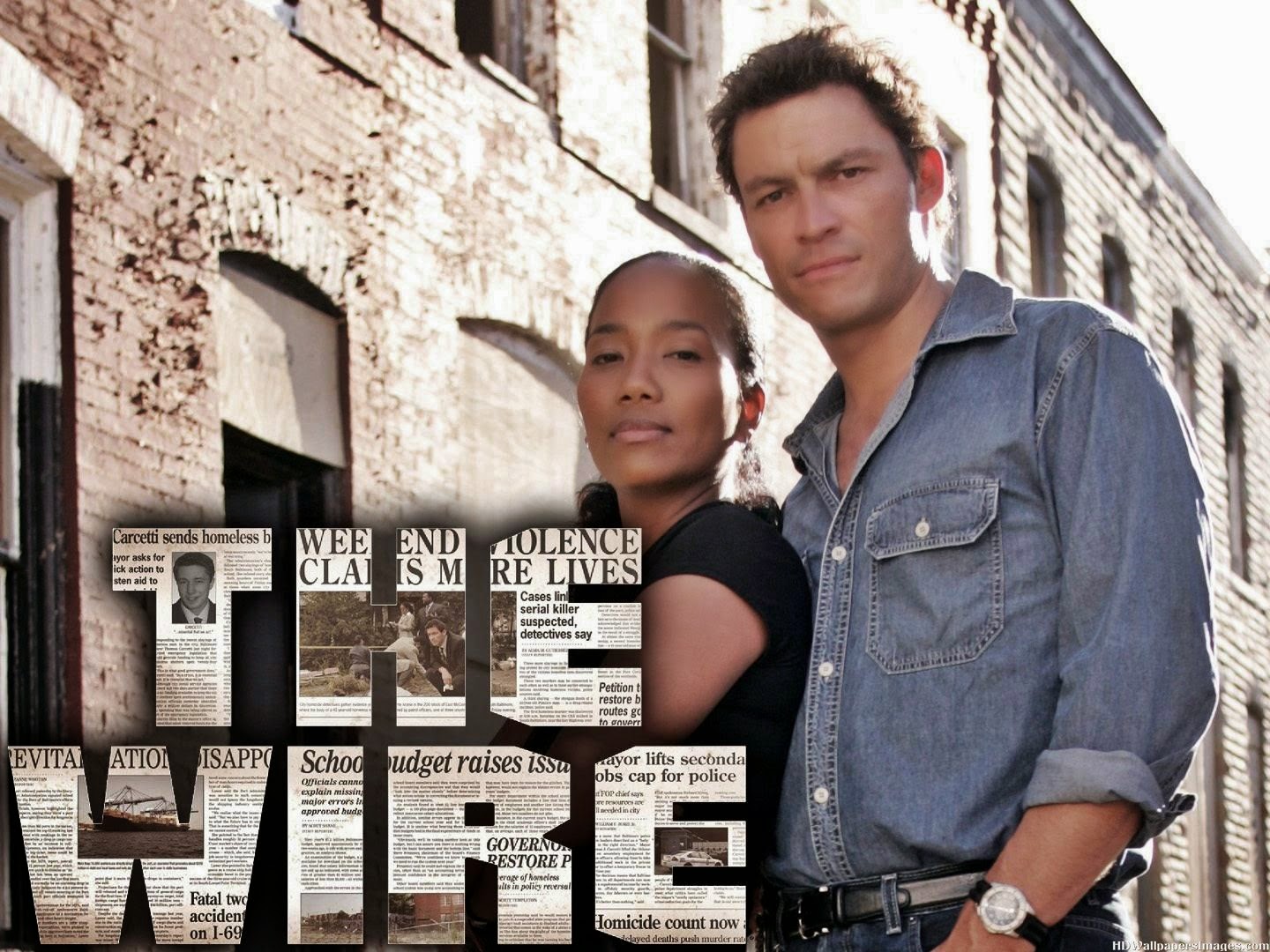

|

| Artist: Tim Doyle |

But I glommed on to the term "ethnographic imaginary" first by reading ethnography and realizing that ethnography always has a problem. It goes to a particular street corner, let's say, and it tries to understand what's happening; but, how can it fully understand what's happening if it doesn't understand the larger world in which that economy of the corner functions? With drugs and street corner stores and all the things that go with it: poverty, etc? You end up attributing a single-sited ethnography to something that is absent. Let's call it the system. And let's say it's capitalism in our society or—what do people like to call it?—neoliberal capitalism.

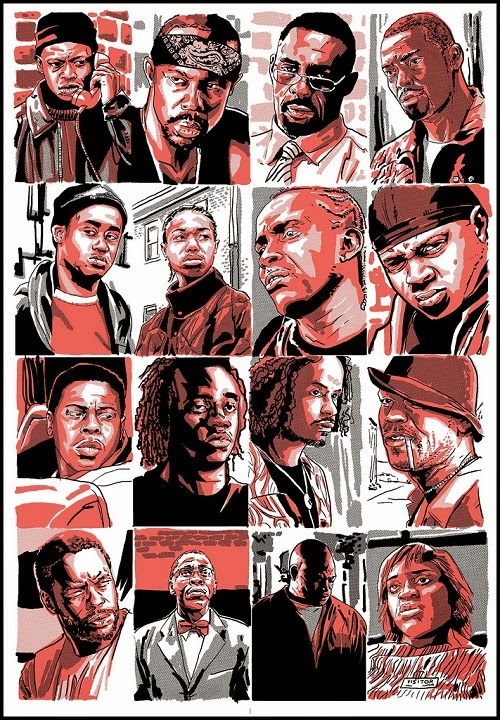

|

| Artist: Tim Doyle |

Once you get this idea of "the fiction of the whole", and the ethnographic imaginary, then you realize that if you move into fiction it's possible to see how all the singular sites work together as a system. That's what initially interested me, but then I thought, "Well, of course, these specific sites are racialized, they're in Baltimore, and many are in inner cities, not entirely but predominantly spaces of especially black men who do not have jobs, who are hustling enough for drugs, or whatever. I began to think that maybe "the fiction of the whole" could be a useful term.

I'm critical of the way in which one critic, George Lipsitz, exchanges the terms racial and spatial. It's one way of accounting for what The Wire accomplishes as a fictional, melodramatic serial. Because the series goes on for so long and because it encompasses so many different spaces, viewers begin to get a notion of the whole. You can't get that notion of the whole without it being fictional but the fiction is related to the ethnography because Simon and his colleagues know that place. Certainly they know the police. Certainly they know the corners. And then they begin to expand to the schools and to the media. Certainly Simon knows the media. He knows the newspapers. Simon built through an ethnographic knowledge of specific spaces an ethnographic imaginary that is, in fact, fiction but which turns out to give more of the sense of the interactions of a whole than I had ever seen! And I've read Balzac! I know how these things work. I needed a vocabulary to talk about what was happening uniquely in this work.

Guillén: Which is precisely what you've achieved.

Williams: But I do think it's important to recognize it as a fiction. The language of The Wire is something that, the more you immerse yourself in it, the more you understand, which is why I don't like the subtitles because then you don't rely upon yourself to learn. A lot of that language is made up. Slang changes so fast. My guess is that nobody speaks that way—maybe they say, "You feel me?"—but nobody speaks exactly that same way today in Baltimore.

Guillén: Once you decided upon the structure, which you've laid out for me, did you approach Simon? Did you run your thoughts by him? Have you two had any interaction?

|

| Artist: Tim Doyle |

If you just follow what Simon says, you end up interpreting The Wire as he wants it to be seen, which is simply: truth. In a way, this does a disservice to the form, the structure, and the power of what has been achieved in The Wire. I wanted to say yes, it's trying to be tragedy, but we don't have Oedipuses today, we don't have King Lears. These are great figures; great human beings who fall. And that's all you get in tragedy, is the fall. And then the fatedness of the fall. It seems to me there's this other force that's operating in The Wire and it's a force that I think most of us respond to in our day and age, which is to say what's wrong and to show how people suffer through the lack of social justice, and that we want to fix it. We want it to be put right. That's the hopefulness of melodrama, which is often disappointed. But it's not a tragic fall. It's not a preordained fall.

So, no, I did not want to talk to David Simon. I wanted to, with my students, enter into an interpretation of what we thought it was. I didn't want to have his intentions articulated once more. I was more interested in a deep reading. But I also got in trouble with Simon. He threatened to sue the press. And I did have to change a few things [she laughs] because he's a feisty kind of man. But what I changed is not important to me, to my reading of The Wire, and had to do with facts about his journalistic career.

Guillén: You've talked about The Wire's televisual elements, its seriality, and you've distinguished between melodrama and tragedy, so now I'd like to approach your concept of "the buffer host"—so important to Simon's previous effort The Corner—but all but eliminated in The Wire.

Williams: Novels have narrators and narrators can sometimes be present in the work. But sometimes the narrator is not a presence and simply says what's happening. What I discovered in Simon's journalism, in his long form and his short form journalism, was a certain tendency for that narrator to be present, and for there to be a strong narrative voice. That narrative voice is, naturally, the voice of a white, middle class man. In reviewing his journalism, I talk about an essay he wrote on metal scavengers for the Baltimore Sun wherein he responded to metal scavengers industriously pulling every piece of copper or metal out of a house even before it's built in order to sell it to get a fix. He writes, "The ants are here; the picnic is us." When you do that, when you use "us", it creates us vs. them, the ants. That voice is the middle class voice disturbed that we are being eaten by these ants. There's nothing wrong with it. It's nice phrasing. But the work of a buffer is going on there. We don't just dramatically get into what the ants are doing. Simon's voice is there to distinguish between us and them.

I felt that in the creation of the dramatized version of The Corner, where actors are playing the real people who are chronicled in The Corner, that the insertion of Charles Dutton at the beginning and at various points was very much to create someone who could buffer us from the raw encounter with the addict who will do anything to get a fix, for example. The fact that Dutton is black and from Baltimore was an attempt I think by the producers of the show—I don't believe this is something that Simon actually wanted—to protect viewers from that raw encounter by creating this once-addict once-street corner man who is no longer that but who is black so you get rid of some of the paternalism of the white buffer of Simon's voice. But there's still a problem in not trusting the viewer and not dramatically structuring what is going on in a way that you can just sort of see it happen. The progression into The Wire, where you do not have a host buffer, where you do not have the literal voice of David Simon, means to me that the drama—and I would say the melodrama—has achieved a state where it can do what it wants to do without using that voice. I applaud that.

Guillén: Can you speak at all to what it might have been in the culture, in the reception of the time, that allowed audiences to be ready for that?

Williams: That's a good question. Among other things, HBO itself had ventured into grittier topics with, say, The Sopranos, which preceded The Wire by a couple of years. The fact that cable television in general did not have the usual prohibitions on language and sex and violence that films had, at least with the ratings system. The fact that Simon's own journalism had preceded and maybe got some people ready.

Guillén: You've described The Wire as a little bit retro with its square screen format and the simplicity of its presentation and you introduce the topic of the allure technology has for law enforcement. The whole notion of "the wire" changes each season slightly adapted to each season's variant narrative. I'm wondering if we can bring this further into the present where there's currently so much discussion about the militarization of the police and the technology being provided them?

Williams: The Pentagon is giving it to them! But I don't actually mean to say that there's not some surveillance technique that's useful to the police. But it does strike me that in The Wire this obsessive search for the better and better technology, the envy that McNulty always has of the FBI man, is meant to be seen and certainly teaches the lesson to anyone open to it that we are too technologically dependent and that there's something about good old-fashioned face-to-face cop on the beat that we lose with the quest and the fetishization of the latest technology.

Guillén: In the compelling distinction you make between tragedy and melodrama, you liberate melodrama from the domestic center of the home and observe it at an institutional level. That made me wonder if, in turn, a nation could be a tragic entity?

Williams: In the common parlance I think that our nation has made tragic mistakes. The invasion of Iraq. It would have been so much better to have left it alone. Yes, you could say there's a tragic flaw in the American character. But I think it's maybe more instructive to say that we are caught up in a melodrama rather than a tragedy, because tragedy is now almost an anachronism to modern culture. Tragedy believes in Fate and the Gods. We believe we can change things.

The United States was adhering to a melodramatic script when it got attacked by al-Qaeda and then thought, "Oh, we have been harmed. We have been injured." There's a terrible flaw in melodrama in that it sanctifies whoever gets hurt, whoever is injured, and whoever is suffering but seems to undergo an alchemy and become—as a victim—automatically good. America had already done a lot of things wrong in Iraq, supported all the wrong people, but all of a sudden we were hurt and we became the victims and we had—in our eyes—the moral right to invade a country. Even though the people who probably brought down the Towers were not in that country. We could lie to ourselves about the weapons of mass destruction and lie to everybody else because we had that apparent moral upper hand. That's the phenomenon that I'm interested in. The phenomenon of injury and suffering which seems to give a certain moral rectitude.

Melodrama is an insidious tool, but it is the way we think. If somebody runs over me with a car, I will feel like a victim and I will play that victimhood to the hilt to try to get whatever reparation I can. We don't accept things like that. Whereas a tragic hero may scream to the Gods but what does Oedipus do? He blinds himself. He so agrees that he did such a wrong thing that he takes the punishment into his own hands. That's a tragic gesture.

Guillén: I don't speak French, but I loved a term you used—ressentiment. Is it safe to say it translates into English as resentment?

Williams: It translates into resentment, but I believe the term comes from Nietzsche and I believe he used it to talk about lesser people, not tragic people, not big heroic people, but lesser people who feel a resentment towards the greater people or the more powerful people. Neitzsche thought it was a terrible sign of his times that ressentiment was such an important feeling. It's a feeling of, "I am wronged. I deserve to get back." But, in fact, it's not coming out of the heroic sensibility of ancient times.

Guillén: Reading your book while watching movies has heightened my appreciation of the melodramatic strengths of those movies. For example, I recently watched Michaël R. Roskam's The Drop (2014), whose narrative protagonist is basically a bad guy, he's a murderer, and a little bit of a thug, who gets injured and becomes morally resentful, which recalled me to a statement you made that most action films are based on melodramatic formula.

Williams: They're all melodramas. We settled on domestic melodrama and soap opera as the definition of melodrama and we like to watch Douglas Sirk movies—I love them myself—but, before those movies, melodrama could encompass action. There are passive victims and active injured victims who get their revenge. Typically, it was the women who would suffer in the home and sacrifice, so we have Mildred Pierce and Stella Dallas and that whole tradition. The other side of it is the action hero who is injured, always, and who then becomes righteous. Bruce Willis is my favorite example but there are a million of them. I don't know why we call those "blockbuster action" movies, but they're premised on an old-fashioned kind of melodrama.

Guillén: Let's talk about some of the characters in The Wire. The one character you did not mention much in your study is Bunk, the character who most captured my imagination when I began watching the series. I thought Wendell Pierce's portrayal was magnificent. You didn't say much about Bunk in your book?

Williams: No, you're right. I have so many regrets about this book, which again had to with how to structure it. It didn't seem right to have a chapter about my favorite characters.

Guillén: For me, Bunk was the realistic voice of The Wire.

Williams: Yeah, and he turns out to be the morally correct voice in the end. There's a television critic by the name of Jeffrey Sconce who says that if you're a true fan of The Simpsons then you not only know Apu but you know the names of his eight children. I asked this to a class once: "If you are a true fan of The Wire, you not only know Bunk Moreland but you know the name of his wife." [Directly at me.] What's the name of his wife?

Guillén: Oh dear, I'm no good at pop quizzes. I don't remember.

Williams: Maureen, or Nadine, or something like that.

Guillén: Nadine sounds right, now that you mention it. Returning to our earlier discussion on the spatial imaginary, as a self-identified queer male I've been considering a queer spatial imaginary and have discovered quite a lot has already been written about that. With regard to The Wire, one of my first obvious attractions to the series was to its gay and lesbian characters, specifically Omar and Kima, and possibly Bubbles. At that time in 2002 I had yet to see queer characters like the ones enacted in The Wire. They maybe didn't reflect my personal queerness, but they reflected a competent queerness, an effective queerness, which inspired me. Can you speak at all to that?

Williams: I think you're right. As with race, the important thing with The Wire is that in a way it doesn't make a big thing about somebody being black, because that's really common, and it doesn't make a big thing about somebody being gay. Which is not to say that there isn't homophobia. Within the book I share some images that show a homophobic reaction to Omar. The Omar character is a rich character and everybody's favorite character, though not always, but often. Part of the reason is because he's a really tough gangster and yet he feels things and he expresses his feelings and he suffers and he mourns and he feels guilty and puts a cigarette out in his palm. He's somebody with very strong emotions and also a strong moral code. In a way he's different from the other characters because he's so good. Aside from the fact that he robs people, he doesn't want to kill them. And sometimes people just give him the drugs. Omar is exceptional and wonderful and I talk about how he overcomes that problem of the "magical Negro." Bubbles is an interesting case because many people don't think he's gay. Only one person has actually said that in print.

Guillén: But there's no question that he's within a homoerotic domain?

Williams: He has repetitive relationships with younger men in which he likes to be the wise man who teaches them. There's no sense that he's sleeping with these men but, yeah, there's something queer about him.

Guillén: You actually say that in your book, that Bubbles may not be gay but he might be queer. What do you mean by queer?

Williams: Queer is a term invented by the queer community that signals that it doesn't necessarily have to do with sexual practices. According to some gay queer activist you just have to think a little different and be a little different and you get to be queer. It's a more encompassing category. There are reasons to be just a little suspicious of it, but it's there.

Kima's interesting because she's one of the guys and wants to be one of the guys and proves herself as one of the guys. It is possible to use someone like Kima to argue that the whole series is insensitive to women. The Wire is really good on race, and it's really good on queer or gay identities, but where are the sympathetic women? That means that you would be counting Kima as a man. The same thing with Snoop. It would be hard to say that Snoop is a lesbian, but she also is a woman who wants to be a man, as Kima wants to be a man, in the social way that men are. So where are the women in The Wire? That leaves us only Rhonda Pearlman really. There aren't strong, interesting female characters, if you go along with the idea that Kima and Snoop are really like men.

Guillén: You suggest further in your book that's possibly due to the fear of associating melodrama with the feminine; the popular mode of the '50s.

Williams: When narrative television drama got to be so serial—it wasn't always serial; it used to be more episodic—but when it got to be so serial, then there was a little bit of a concern that it might be regarded as soap opera. That may be the reason to account for the insistent maleness of so many of the television dramas: Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, Deadwood.

Guillén: And why Orange Is the New Black....

Williams: ...is so refreshing!

Guillén: In trying to understand narrative issues of identity, the danger of fixing things into nouns has long irked me, instead of finding comfort in the flexibility of adjectives. In other words, instead of being a melodrama or a tragedy, it might be more useful to point out how a film has melodramatic or tragic elements. As a professor of rhetoric, can you say we are too hooked on the fixed quality of nouns?

Williams: Well, you have a point but I don't just want to use the word "melodramatic" first of all because that always is a term of disapproval, whereas melodrama once existed as a thing that people liked. "Don't be so melodramatic," we say. One of the things I'm trying to do is to rehabilitate the noun melodrama and to understand it a little more historically. If we understand it a little more historically, maybe we can see that its reputation goes up and down at different times and that we would not dare call the brand-new serial television that we're all watching melodramatic because that's a form of abuse. I'm saying, let's look at what melodrama is and has done and let's look at how it doesn't want to call itself that anymore. I want to reassert the noun.

Guillén: And you've done that well by posing the difference between melodrama as genre, which is how I think most people think of melodrama, and melodrama as mode. Can you speak to that?

Williams: In film studies this has been a real problem because we are avidly interested in the genres of cinema.

Guillén: And in recent years there's been a lot of talk about elevating genre.

Williams: Yes, and that's why David Simon insists The Wire is not a cop show. I think it is a cop show and a lot of other things. Why do we have to deny genre? Because it's low. When we think of melodrama as a genre, we actually lose the sense of genre, because I would say that science fiction, action, westerns, crime thrillers, almost all of those would have what I like to think of as the structure or the skeleton of melodrama. To say melodrama as a genre usually refers to just those women's films. Every now and then one gets made and we all cry but that's to ignore all the guy-cry movies that are very popular but never called melodrama because they're manly.

Guillén: So what do you mean by the "mode" of melodrama?

Williams: You wouldn't say that realism is a genre. Realism is a mode. Realism is a way of telling the story. My argument is that melodrama is a chameleon-like mode that often interacts with realism. But if the purpose of the story, if the way it makes you feel, is to watch it and right a wrong or fix an injustice or judge the fairness of something, then it's better to call it melodrama making use of realism and bringing into the realm of the representable things that typically have not been represented, like drug addicts.

Guillén: When The Wire came out in 2002, and I was watching it on HBO and had to wait each week for the next episode, I found it difficult to keep up with things.

Williams: By "keep up" you mean "hard to remember"?

Guillén: Yes, because there were so many characters, so many sites, so much going on. Then, towards the final seasons I gave up watching on HBO and waited for each subsequent season to be available on DVD, which I would then watch in batches of three or four episodes per disc. Now I binge. The availability to visually binge on a series helps me absorb its narrative traction. Any thoughts on the changes in viewer reception and their capacity to absorb what The Wire really has to say through binge viewing?

Williams: First of all, perhaps the history of serials can be instructive. It was in 1837 that Dickens wrote The Pickwick Papers and—instead of publishing the novel—he published parts of it and people started buying it. Some of his novels were weekly installments and some of them were monthly installments. Sometimes they were in magazines and sometimes in penny installments; sometimes 20 installments once a month. And somehow people were holding all of that together. There were the bingers among them who would wait and collect all of the installments—but still the novel hadn't been published as a whole—and they would binge on the parts.

Guillén: Like some collectors do with graphic novels and comic books?

Williams: Yes. Bingeing has always been with us. The ability to binge is greater now with DVDs; or to, at least, binge on a season, if not the whole. Part of the problem with bingeing is—if you wait too long—you don't get to be part of the conversation that everybody might be having, although it's hard to know where and when that conversation is taking place. I don't know if you do much television criticism?

Guillén: A bit of short form commentary on social media, but I primarily just watch lots of television. I mainly write about film, but I'm getting tired of writing about movies because I'm finding the better stories are on television.

Williams: That's what's happening. But then when do you write about television? When you see a movie, you have something to say about it but when do you say something about a serial? Only when it's over? Or at the beginning? Or in the middle? It's a real issue.

Guillén: You've talked about melodrama having an impulse to right a wrong and you've shifted melodrama out of the personal realm into an institutional realm....

Williams: Well, it can be and, again, The Wire is the example.

Guillén: As one citizen to another, I'm troubled by the fact that—even though we know so much more now and are more articulate about what's going on and the pressures impacting our lives under neoliberal capitalism—we seem unable to do anything. Reading your book, I kept wishing everyone could take a class in melodrama to understand what they're doing (or not doing) and then maybe we would have a fighting chance. Can melodrama truly offer remedy to social ills?

Williams: No, it can't. I wrote this book because I thought The Wire was the best use of melodrama I'd ever seen, the most intelligent, equally dramatic and compelling, and yet socially relevant and engaged. We can see that the war on drugs is stupid. But I'm acutely aware that melodrama is not always on the side that I want it to be. I learned this lesson many years ago when I began teaching one of the most famous movies in American history and probably the film most responsible for making movies popular to large audiences, which was The Birth Of A Nation, which is....

Guillén: Hard to watch.

Williams: ...a powerful melodrama and not hard to watch if you just give yourself up to it and there you are rooting for the Ku Klux Klan at the end of the film. That's the power of melodrama. The Ku Klux Klan, as that story is told, was being terribly abused and injured by these former slaves who wanted to rape their women. The Klan had to ride to the rescue. Melodrama is neutral as far as position. You can have strong melodramas on the side of Ceaușescu, or all of the melodramas prevalent in Hitler's Germany. So it's not like melodrama is the answer.