Triple-crown award winner Ellen Burstyn claims she realized as a young actress that she wouldn't be able to rely on her looks if she wanted to have a career, and yet at a spry 83 years old, Burstyn is undeniably gorgeous. A last-minute announcement (only three days before the festival) and a last-minute venue change to the Victoria Theater may have accounted for the sparse audience (75-100 people) for the onstage conversation with Ellen Burstyn, the recipient of the Peter J. Owens acting award for the 59th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF); but, though at first seemingly disappointing, the small audience actually allowed for a closehand intimacy with a forceful talent. Had this event been at the Castro Theatre, it would have been an altogether different animal.

Peter J. Owens (1936-1991) was an actor, a film producer, a philanthropist and an important supporter of the San Francisco Film Society, who remain grateful to Scott Owens and the entire Owens family for continuing his legacy by endowing this award, which honors an actor whose work exemplifies brilliance, independence and integrity.

In his introduction to their onstage conversation, SFIFF Executive Director Noah Cowan noted that when it came to Ellen Burstyn, it was difficult to avoid her "triple crown". She's one of the few performers who has won an Emmy®, an Oscar®, and a Tony®. In reviewing her work, he found her performances daring, gutsy, and impressively diverse.

Arriving to the Victoria stage after the festival's clip reel, Burstyn joked, "I feel like I've just seen my whole life pass before me."

Cowan stated that—in researching Burstyn—it quickly became apparent that her outstanding career had not been one of "comebacks" but, rather, a consistency of exceptional work decade after decade, film after film. He wondered if that hadn't come about because fame came later for her? It didn't arrive until she was 42 and won her Oscar® for her performance as Alice Hyatt in Martin Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974). He queried how important her formative years had been in creating the hardworking actress she is today?

"I never wanted to be a movie star," Burstyn replied thoughtfully. "I always wanted to be an actress. I figured out pretty early on that—if I depended on my looks—I would have a short career. I had to learn how to be an actress. It took me a while to figure that out. At a certain point I saw the work of actors like Marlon Brando, Jimmy Dean, Kim Stanley, Geraldine Page and noticed that they knew something I didn't know. They were doing something I didn't really understand. I left the career I had in Hollywood for New York and studied with Lee Strasberg. I learned the art of acting, which is a different thing than a superficial presentation of yourself."

Cowan noted that the Strasberg School remained of importance in Burstyn's life. Along with Martin Landau and Al Pacino, Burstyn is one of the chief mentors at the school. He asked her to talk a bit about what studying with Strasberg brought to her and what the school brings to other actors?

"First of all," Burstyn answered, "there's the Actors Studio, which is a workshop for professional actors. You audition to get in and, once you're in, you're in for life and you use this studio whenever you need to for whatever you're working on. Then there's our school, our Masters Degree program at Pace University in New York. That's an accredited school where you get a degree. My training was at the Actors Studio with Lee. What I learned from him—I can't say it changed my life, it made my life—because my values weren't very developed until I went to him. He's the one that really introduced me to depth living, I would say, just because of the intention of what you're doing and your willingness to go deep. I didn't know about that before and I did learn it from him.

"When he died, by that time I was a member of the board and I was one of the moderators (he had asked me to be one in the '70s). We say moderators, some people might say teachers, but we like to keep a little distance from the teacher-student relationship when we're talking to actors with careers. After he died in the 1980s, I ended up being a president along with Al Pacino and Harvey Keitel, and currently I'm the Artistic Director and have been for quite a while. I moderate every Friday that I'm in town. The Actors Studio is the place I learned how to be an authentic human being and, therefore, qualify as an artist. I feel that there are very few places in the world that are free to actors to give them what is essential for them to practice their craft, which is the stage and an audience."

Cowan described her performances, as in The Exorcist and Alice, as iconic moments of '70s cinema and commented on how she didn't seem to care what genre she worked on, attracting roles that ran the gamut from dramatic to light comedic to horror and thrillers, which he deemed unusual.

"Is it?" Burstyn responded, surprised. "I never thought, 'I'm going to do this genre and not do that genre.' I can do comedy when I'm offered it. And I can do drama when I'm offered that. It's never been important to me what kind of film it is. What's more important is what the role is and what the film says, what the stories are."

When people discover Martin Scorsese directed Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and they watch it, Cowan assessed, they discover something different than what they associate with Scorsese, because it was actually Burstyn who made that film happen and brought Scorsese on to the project. Cowan asked her to recount how all that happened.

Burstyn: "I was shooting The Exorcist in New York and the dailies were going back to California, to the President of Warner Brothers at the time and he called my agent and said, 'We want to do another movie with her.' He sent me all of the scripts that they already owned. This was in the 1970s when the Women's Movement was just coming alive. Women were going through the transition where they were realizing—as my character said in Alice—that 'I'm going through my life and not some man's life I'm helping out with.' That was the transformation of consciousness that was happening at the time. All of the scripts that they sent me were the old way: women were either the loyal wife who stayed home when the hero went out to save the world and then—when he came home—she had hot chocolate waiting for him; or she was raped and beaten and a victim; or she was a prostitute with a heart of gold. They were all pretty stereotypical characters so I told them I didn't want to do any of those. I went out looking for a script that could reflect a woman as I understood women to be: as full human beings.

"I came across Alice and I brought it to Warner Brothers and they said, 'Let's do it. Who do you want to direct it?' They asked me if I wanted to direct it and I said, 'No, I'm not ready to direct and act at the same time, thank you very much.' So they asked, 'Who do you want?' I said, 'Someone new and exciting.' I phoned Francis Coppola and asked him who was new and exciting and he said, 'Look at a film called Mean Streets.' It had been made but not released. Warner Brothers owned it so they played it for me. I asked for a meeting with Marty and he came in—this very nervous little guy—and I said, 'I saw your film. I really liked it. But Alice is a film that's told from a woman's point of view and—in looking at your film—I can't tell if you know anything about women? Do you?' He said, 'Nope, but I'd like to learn.'

"So we did it and, of course, I had no idea that I was hiring one of the great film geniuses. We rehearsed and, in rehearsal, we did improvs and they were recorded. At the end of the day the ones that we liked were sent to the screenwriter, but there was a nod to all of us. We all created that film."

Cowan wondered if she felt not enough has changed for women in the film industry since Alice; if she felt there had been progress?

Burstyn: "I think there's been progress but it's been slow, as progress always is. Look how long we've been trying to outgrow racism in this country. It takes time. There's progress but there's a long way to go. The same with women. We live in a patriarchy, let's face it. To make a change in the patriarchy towards equality of the sexes takes time. I was just in Stockholm this year and I noticed there were a lot of women in executive positions. I mentioned it to one of the women and she said, 'Yes, we've had gender equality for two generations now.' I said, 'How has that worked out?' and she said, 'Really good.' I said, 'Why is that, do you think?' She said, 'Well, what we've discovered is that women work for consensus and men work to win.' Isn't that good? Don't we know that to be true? So it's run very well over there."

Cowan pursued the rumor that Burstyn was planning to direct a film.

Burstyn: "There was a script that I was sent to act in and I had just been thinking, 'Y'know, I've never directed a film. I meant to do that and somehow let that get away from me.' They sent me this script called Bathing Flo, which I really liked, and I said, 'Definitely. I want to do it.' They said, 'Well, who would you like to direct it?' It was like an answer from the Universe! I said, 'How about me?' They said yes, so we're in the process or raising money, which I want to tell you is the worst part of the business than I ever imagined. We've been trying to raise money for a year. We've come close but it hasn't happened yet. We currently have a financier who's interested and will give us his final word later this month."

As she gears up to direct, Cowan inquired how it has been to take direction from so many great directors?

Burstyn: "It's wonderful when you work with someone like Darren Aronovsky, who I adore, he's so smart and so kind and so good. I remember one scene we did in Requiem For A Dream (2000). We always did several takes and they would always vary. We finished a scene and he came up to me and said, 'Okay, we've got that in the can'—at which point he would usually say, 'Let's move on'—but, this time he said, 'Let's do one more and do whatever you want.' His saying that freed me to do something I had not done in any of the takes that is the take that's in the film. It's such a good lesson for directors: to take all the obligation off the actor or actress and just let it go, let it rip, and very often that inner motor—whatever that thing is that we have inside—suddenly gets released and something unexpected comes. I consider that a really good director."

Cowan asked: Did you know what you were getting yourself into when you accepted the role of Sara Goldfarb in Requiem For A Dream?

Burstyn: "I turned it down. When they sent me the script, I read it and I went, 'This is the most depressing script I've ever read in my life. Who wants to pay money to see this?' 'No,' I said to my manager, who was then my agent, and she said, 'Well, before you say no, look at a film called Pi.' Pi was Darren's first film. I said, 'okay' and put it on and it was not even four minutes, maybe four minutes at the most, and I went, 'Ah, I see. This guy's an artist. Okay.' So I called back and said, 'I'm in.' Then I met him and fell in love.

"While filming Requiem, I had the great good fortune of having Darren's mother on the set every day and that's her accent I'm doing. Darren's mother and father were on set every day. When Darren did Pi, she was the caterer because he couldn't afford to hire a caterer. They're wonderful people. Darren's father is a professor and she's a teacher too. I would talk to her every morning and she would help me get into not only the accent but the mannerisms. Basically, Sara Goldfarb is like all of us. She had desire to be more, experience more, be loved, be looked at and seen. Those are rich things to play with and to work on."

Cowan noted that toggling between stage, screen and television has been the hallmark of Burstyn's career. Aware the Actors Studio grounded Burstyn in very specific ways for whatever she was doing; he nonetheless wondered if there something different about those three mediums for her in how she approached them? Do they inform each other?

"The real work of acting," Burstyn reminded, "is an inside job. That is the same in any medium. The expression of it might be different. I remember this moment—it was one of my favorite moments making a film—in The Last Picture Show (1971). There's a scene where I'm sitting in a chair looking at television and thumbing through a magazine, bored. My husband is sitting there asleep and I'm bored! Then I hear my lover's car drive up. Yay! I get up and run out of the room I'm in. It's a tracking shot with a camera following me. I get into the other room to open the door ('Yay, I'm going to see my lover!'). I open the door. My daughter's there. Damn! It's not my lover; it's my daughter. But wait a minute. That was my lover's car. My daughter just got out of my lover's car. She's in tears. Oh … they had sex. Oh, my daughter's not a virgin anymore. Oh, poor thing, come here, honey.

"That was a scene with no lines, okay? I say to Peter Bogdanovich, 'Peter, I have eight different moments from here to the door and no lines.' He got this impish smile on his face and he said, 'I know.' 'Well, how the hell am I supposed to do that?' He said, 'Just think the thoughts of the character and the camera will read your mind.' Yeah. So you can do that with movies and television, but that won't work on stage. But what does work everywhere is to be real. If you're real, the audience gets it, whatever it is."

"Do you have a preference?" Cowan asked.

"I love the stage," Burstyn answered without missing a beat.

"Why?" Cowan pursued.

Burstyn: "The rehearsal process is so interesting. To go into a great play like, for instance, my favorite play I ever did was Long Day's Journey Into Night. To really go into that character in that play, and the history of Eugene O'Neill and that family and the things they were doing to each other, what they represented, it's just such a profound experience. To me, the rehearsal period is the richest time. The performance of it becomes like another life you're living; like you have an alternate life. The communication that happens with an audience; there really is an exchange of energy, thought, feeling, emotion, and you get it. The audience gets it when you get it."

Cowan queried whether there was any character, any stage persona, Burstyn still felt she wanted to play; that was still inside of her?

Burstyn: "I still want to play Mary Tyrone. I never got to do her in New York. I hate every actress who plays Mary Tyrone in New York. I saw Vanessa Redgrave do it. She's one of the greatest actresses in the world and I adore her, but I almost threw tomatoes at her. Now Jessica Lange's doing it in New York. [Scowling] Jesus! I tell myself, 'Life has disappointments.' "

Cowan observed that Burstyn has been part of a movement that has happened in the last few years where long-form television has seized the zeitgeist by recently portraying Elizabeth Hale on five episodes of the Netflix series House of Cards. He expressed that it felt like she had come full circle as much of her early career had been on television. Yet now so many people know her because of House of Cards, which has had a huge public cultural impact. He asked her for her thoughts on the popular rise of narrative seriality on TV?

Burstyn: "When they released the current season so you could stream House of Cards that weekend at the beginning of March, I went out to walk my dog at 7:00 in the morning and everybody in Central Park had seen the full season! I couldn't believe it! I mean, the fan base for that show is just amazing. I've never experienced anything like it in my career. It's an interesting transition because multinational corporations have bought the movie studios and they're not in the business of making movies; their business is making money. They have a formula of what will make money. If Spiderman 150 will still make money, they'll make that.

"The film business as I knew it in the '70s and even into the '80s and early '90s, has dropped through the floor into the independent film movement. That's where 'cinema' is. Not the action-adventure films but films about people. But there's no money down there. Everybody who's working there is working for almost free. At least the actors are. I'm sure the producers aren't. What has happened in the meantime is that television has now become another place where real writers sell their work. There's really good writing going on in television, which is now becoming a much more—what should I say?—respectable art form in a way.

"The only thing is that their schedules are killer. They're really tight. Art takes time. You can't just whip art together. You can whip together a TV show; but, in order to do something really good, you have to have time. They're just beginning to have enough schedule to allow for good work. Let me tell you a story about House of Cards. You've seen it? Okay, you know the scene where I pull off my turban and say, 'I'm the mother. I'm the mother. I'm the mother.' As it was first written, it said I open my robe and pound on my bare torso saying, 'I'm the mother. I'm the mother.' I said, 'Gentleman, that is not going to happen. We will find another way.' I had a later scene where she finds out that I'm bald when she finds the wig. I said, 'Why don't you let me be bald, wear the turban, rip off the turban, and do that?' They said, 'Okay.'

"But then when we went to shoot, we discovered that it was four hours in the make-up chair to make me bald and they couldn't afford to do that for two days. So they said, 'We're going to have to do both scenes in the same day.' Which meant that I did about an 18-hour day. Which is not easy, even if I weren't 83 years old. So we did it. I got through it. Fine. Then they call me and tell me that they fired the camera man because the lighting was so bad they couldn't see me and they had to do the whole thing over. I did. I came back and did another 18-hour day."

"So the rage was real?" Cowan quipped.

Burstyn: "But, you see, if this were 10 years ago, they wouldn't have re-shot those scenes. They would just let it be whatever it was with whatever they could do in post-production. It's a step forward for television that they actually care enough about the quality to re-shoot a tough day like that."

At this juncture Noah Cowan opened it up to the audience for questions. I was first: "Ellen, it's so wonderful to have you here. It's such a delight. Thank you so much. Requiem For A Dream, to me, is one of the most harrowing performances I have ever seen; you were absolutely brilliant. Earlier you were talking about performance as depth, a depth performance, and in Requiem you take a dark descent. My question is: how do you back up from a performance like that? How do you move out of such darkness back into 'normal' life?"

"Do you know how I feel at the end of the day after doing a really harrowing performance like that?" Burstyn asked me. "Elated. I feel wonderful. Nothing feels better than doing a good job, whatever your job is. At the end of the day I just feel happy."

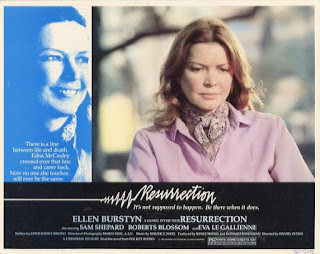

Cowan interjected that he could have asked a similar question about her performance as Edna in Resurrection (1980) because of the intense empathy of that role. He asked if it was hard to park a performance at the end of the day? To leave it on the set?

"No," she reiterated calmly. "I don't understand these stories from actors who say that they have to get away from the world. It just feels good. Resurrection is a film that I contributed a lot to; there's a lot of me in that film and what I was studying at the time. I think doing a job well is one of the most satisfying things anyone can do. I remember when I was preparing for Alice, I read Studs Terkel's Working where he interviewed people about their work. I found that they all took such pride in their work and that was where their flow was, when they could do a good job. I put that into Alice. I added that she really liked being a good waitress. Even though she wanted to be a singer and was waitressing as a day job, she felt good when she did a good job. I think that's very important in life and where we get the most satisfaction. I don't have any difficulty doing dark roles. I mean, at the time if it's an emotional role and heart-wrenching, I might make myself miserable. As I said to an actor at the Actors Studio the other day when she said, 'But it hurts', I said, 'Yeah, but that's the sacrifice we make for the people. That's what we do.' "

Q: You starred with the great Greek actress Melina Mercouri in A Dream of Passion (1978). What can you tell us about your relationship with her?

Burstyn: "Let me tell you a funny story about Melina. She was married to Jules Dassein. He was one of the great writers who was blacklisted. He went to Paris to live and his career from thereon was in Europe. He married Melina and wrote and directed A Dream of Passion. One day Melina comes to me and she says [Burstyn imitates her whiskey-throated voice], 'Do you like what I did there?' I said, 'Yeah, I think it's good.' She says, 'You don't think it's too much?' I said, 'No, Melina, I don't think it's too much.' She says [sobbing], 'Tell Jule!' I said, 'You tell him, Melina, he's your husband.' She said, 'He has this antagonism towards me.' "

Q: How do you convey to young actors that the work is going to take time? That they're going to have to be patient and that it's not all going to come overnight? What words of advice do you give to those young actors?

Burstyn: "I can tell you that when I studied with Lee, and I already had a career on stage, in film and on television. I started studying with him and doing the work that he taught, which is basically how to be real. The first time I worked with him, he said, 'You're very natural, darling, but you're not real.' Finally the day came when I was real, and not only in the Studio, but in my work. Being real is one thing when you do it for Lee in the Studio in a safe environment, but then when you try to bring that work to a picture that has to be shot quickly, it's not always possible. Or rather, it's possible but you don't always succeed. So I finally did it—I think it was The Last Picture Show, actually—and Lee saw it and he said, 'How long have you been studying with me now?' I said, 'Seven years.' He said, 'Yes, that's about what it usually takes.' It's not easy. Taking off the mask that you've been brought up to think is the right way to be—the nice, polite, acceptable, conventional way to be—and to be willing to peel that off and let show who you are underneath, that is hard."

A young woman admitted that she considered Burstyn to be one of her favorite actors and an extraordinary artist and that she is still mad to this day that Julia Roberts won the Oscar®. She wondered how Burstyn handled it?

"You know," Burstyn grinned, "I still have people who walk up to me on the street and go, 'You were robbed.' At first I didn't know what they were talking about. How do I handle it? I saw Julia Roberts on television the other night in an ad for a new movie she's playing and the thought that went through my mind was, 'You've got my second Oscar®!' "

Monday, April 25, 2016

Sunday, April 24, 2016

IFF PANAMÁ 2016: EL APÓSTATA (THE APOSTATE, 2015)—The Evening Class Interview With Federico Veiroj

Federico Veiroj's long-awaited third feature El Apóstata (The Apostate, 2015) had its world premiere at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival, continued on to the 63rd San Sebastian International Film Festival (where it won both the FIPRESCI Award and a Special Jury Mention), and made a striking appearance in the rich, diverse Ibero-American Portal programmed by Diana Sanchez at the recently-held 5th edition of IFF Panamá.

As synopsized by José Teodoro in IFF Panamá's program capsule: "Sleepy eyed madrileño Gonzalo Tamayo (co-scenarist Álvaro Ogalla) is a dreamer. Though well into his 30s, he has no career, no compulsion to complete his studies and no romantic life to speak of. But he has decided on one clear goal, one ambition to animate him with a sense of purpose: to apostatize from the Catholic Church. Will the Church's archaic bureaucracy prove too labyrinthine for our slacker hero to navigate? Imaginative, sexy, and composed of one elegantly rendered image after another, Uruguayan Federico Vieroj's The Apostate is a sophisticated, Iberian spin on the man-child comedy."

The Apostate is scheduled for two upcoming screenings in the 59th San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF), currently in progress, where Robert Avila notes in his program capsule: "More than a portrait of a man unwilling to fully grow up, The Apostate prompts subtle questions and subversive pleasures in its battle of wills between a would-be renegade and some of the more intimate institutions of social control."

Lead actor / co-writer Álvaro Ogalla is expected to attend these SFIFF screenings and—in anticipation of my own scheduled conversation with Ogalla—I offer my earlier conversation with director Veiroj from IFF Panamá, in turn anticipating the film's North American theatrical release through Breaking Glass Pictures, who acquired the film from FiGaFilms, who have likewise sold The Apostate to a host of territories, including France, Mexico, Brazil, Panama, Argentina and Central America.

As profiled on the SFIFF website: "Born in 1976 in Montevideo, Uruguay, Federico Veiroj began making short films in 1996, first entering festivals with As Follows (2004), a warm and witty coming-of-age tale set amid the filmmaker's own Jewish subculture of Montevideo. His first feature, Acne (2007), premiered in the Directors' Fortnight at Cannes and garnered accolades internationally. His follow-up, A Useful Life (SFIFF 2011), a loving and deftly drawn black-and-white homage to a life in the cinema, won the Coral Grand Prize for Best Film at the Havana Film Festival."

[This conversation is not for the spoiler-wary!!]

Michael Guillén: In your conversations with Danny Kasman at MUBI's The Notebook and José Teodoro at Film Comment following the film's world premiere at TIFF, you've made it clear that The Apostate is less concerned with a sociopolitical critique of the Catholic Church, and engaged more with the fanciful query of whether or not one can break with the past and, in gist, erase its effects. The presumed answer is no, and this is confirmed by the lovely image where we are shown our madrileño protagonist Gonzalo Tamayo (Álvaro Ogalla) with his shoe laces untied. The camera pans around the room and returns to his untied shoelaces, though now on Gonzalo's boyhood shoes, suggesting that he has not changed since childhood. Is this image a wry comment on the impossibility of the task Gonzalo has set for himself because of the very nature of his character? Can you speak to how in your films the strength and / or purity of image guides narrative? Alternately, how image becomes the script, is the script?

Federico Veiroj: One of my first inspirations was to work on a film based on an impossible task for the main character; let's say, to change something from his own past. But, working on a film and all the fantasy possibilities that it gives me as writer and director, I wanted him to really achieve it. So, with regard to your question about "images that guide narration", I would totally say yes, they do. I knew the ending of the film before having the last version of the script, and found myself in the grip of this very powerful image of Gonzalo that I knew was symbolic and poetic and that was dictating what the narration needed for its ending.

The sequence with the untied shoe laces was something very important for me during the script process because it was exactly that—Gonzalo's own mirror—and for him to even react (with a smile) to this memory was impossible to escape, which I now recognize every time it appears. The shoe lace sequence had to be strong because it was the only moment where we are in touch with a "harsh" or "aggressive" sensation from Gonzalo's past, but it had to be done with poetic simplicity. That's the kind of sequence that I imagine during script writing that is then difficult to shoot because there are many levels of interpretation that I need the audience to feel. Each decision as to the details of such a sequence, no matter how small—the kind of shoes, the trousers, that particular leather jacket he was wearing, and obviously the tiles of the floor (like a life transition)—are all important. I also had in mind the action of his stealing a vinyl single, which for me was the perfect size, because it stood in as a metaphor for his being a child. I guess I felt that his stealing a big LP would have been over-acted or seen as something overly important, and I didn't want that sensation.

Also, I would like to say that some of the music that I knew I was going to use was also an inspiration for some of the film's sequences, providing mental images. That was the case with the mellow classic music from NO-DO (Franco's documentary and newsreels department which made propaganda films, but also "anthropological" documentaries on traditions, on geography and many aspects of Spanish life and social life from 40's to late 70's). I was aware that some parts of this NO-DO music would elicit special feelings of the past that I had to take advantage of.

So, to summarize, I would say that in my case a film is made out of sequences that will be built together with my production designer and art director during the process—two people who I trust a lot—combined with other sequences I've already scripted, which we build as we adapt to shooting conditions. Sometimes there are elements that appear during scouting. In all cases, what guides me is always the mixture of narration, emotion and poetics. I rely and trust in this mixture because I believe in beauty and complicity with the audience. Sometimes deep emotions within certain shots or sequences arise from this combination.

As for the sociopolitical elements you mention, they appear when all the elements of the narration are in place. In any case, I am not naïve. I knew that the political act of a man questioning the ambiance of his present situation in Spain, which—more than criticizing the Catholic Church, I would say, admits to its big influence on every aspect of life—was also going to be a multiple level metaphor.

Guillén: How important was it to add an epistolary layer; i.e., the voiceover of Gonzalo writing letters to his "friend" to explain and / or justify his desire to apostatize? Instead of, let's say, writing an email? Clearly, his desire to apostatize is not just a religious gesture? As you've indicated elsewhere, "To apostatize is not something that you do just with religion. You can do it with your life. It's about embarking on life's journey on your own terms." I'm aware this film is based upon Álvaro Ogalla's personal experience of trying to apostatize; but, have you felt this impulse similarly anywhere within your own life? Or, more specifically, within your filmmaking?

Veiroj: First of all, the idea of Gonzalo writing a letter to a friend was a cinematic and universal device intended to place the film in the world of a fable; a world where all could be fantasy or memory built for a letter narration. An email is not like a physical letter whose imprint will remain (which bears relation to his purpose in the film "to erase" his past) but also I wanted to use correspondence as a means to blur the definition of time, to suggest that this story could be located in our contemporary moment or 30 years ago. I thought a letter provided the perfect mode to combine his confessions and inherent intimacy.

Further, I believe Gonzalo's approach to life operates at a high romantic level, as with Álvaro Ogalla—the actor, co-writer, and inspiration for this story. Álvaro's real-life attempt to apostatize from the Catholic Church in Spain was truly inspiring to me not only because of the peculiar fact of its meaning, but also because I knew in a film it would offer different levels of interpretation. Gonzalo is questioning himself about religion, family, work, and every established institution that reigns and guides our lives. He just wants to live life in his own way. Obviously, there's something completely utopian in such an endeavor, which is the kind of issue or idea that in a film becomes real. For this film, I liked the idea of working on that level of unrealistic purpose because it was the perfect way to narrate Gonzalo's mood and his place in the world.

As for your more personal question towards me and my film making, I can only say that I am a curious person. I let myself go every time I can. I always need new challenges for my work. So far, I haven't had any desire to apostatize from anything because I always do what I want. I can't give up my ambition to make new films or to build new artistic relations while making films; it's beautiful and so gratifying. Without new film challenges I get bored. I always want to dive into new oceans—or, at least, to have my own fantasy of diving into new oceans—and I've never liked to do things that I knew I would be good at, or efforts with predictable results. I guess making films for me is like gambling with aesthetics and emotions, and I like it. And since I also want to discover new music, new art, new films, etc., I can say that I can't give up something that's a passion. So, if no decay of the passion arrives, my plan is to keep doing what gives me pleasure, in film and in every aspect of life. Finally, I believe "to apostatize" from something is simply synonymous with recognizing the importance of it. That's also a way of having a close relation with something—even with something that you want to avoid—because it's consuming your energy and thoughts. Again, I feel that Gonzalo's intention to abandon something which he fully represents is so beautiful because it's his way of expressing how important these issues are for him.

Guillén: There's a bit of masochistic pleasure derived in Gonzalo trying to step away from the Catholic Church using the rules of their bureaucracy. Does this align him with the flagellant witnessed early in the film? Can you speak to the illicit aspect of pleasure that Gonzalo is experiencing by chafing against the Church?

Veiroj: The flagellant could be Gonzalo. He could be any of us who are victims of our beliefs and desires. In any case, the bureaucracy is justified because I wanted Gonzalo to feel the frustration that his case isn't an issue for anyone inside the Institution, nobody cares about him, he is just one more person. That sensation kills him, yet gives him more energy to achieve his task. For Gonzalo, receiving negatives from the Church deepens his desire to apostatize. Admittedly, the difficult process and bureaucracy to apostatize presented in the film is not based in reality but I wanted to exaggerate it because I needed that funny, tender and aggressive tone of Gonzalo's reaction.

When I talked about fantasy before, I meant to say also that I like to explore a character's reaction to things that would only happen within a film on a screen; the symbolism and the emotions are the important aspects here. If we judge Gonzalo by the laws of the real world, we could say his actions are illicit; but, within poetry, aesthetics, and the film world he lives in, his actions are totally licit. In any case, Gonzalo considers what the Catholic Church is doing to him as illicit, causing him unnecessary suffering, even if it's not really that much nor important for other people. The point of view of the film is necessarily Gonzalo's; his codes and laws are the ones I have to follow for the narration. His journey includes some pleasant moments, like recognizing the ring of the priest, recognizing some old religious lessons during his conversation with the bishop, and I am sure his final act is full of pleasure; it's all mixed because he is seeing himself in the past and remembering things, remembering old feelings and bringing them into his present (like his relation with his cousin), and even old complicities (like the one he has with the friend he is writing to). So, yes, I agree with you that Gonzalo may be enjoying some masochistic pleasures.

Guillén: Pursuing how the text of a script can be textural, i.e., layered, your choice of non-diegetic music is essential to shaping and presenting this epistolary fable. You incorporate the music of Hanns Eisler, Federico García Lorca on piano for "Romance Pascual de los Pelegrinitos", and Prokofiev's music for Alexander Nevsky. As much as Gonzalo is trying to break away from the past, the music in your film insists on a historicity that clings affectionately to the past? Explain your purpose in setting up what feels almost like an archival impulse? Certainly, archival practice is present in your unearthing Lorca on the piano and the aforementioned music you've used from the Franco-era NO-DO newsreels. This impulse comports with the archival flourishes in A Useful Life. How do archival practices influence your imagination and scriptwriting?

Veiroj: I thought Lorca's romance was perfect to present Gonzalo's character, because—apart from its beauty—I believe the sound situates the audience in the film, in the fable. And I also knew NO-DO music was going to be used in some parts of the film because of the sweet and melancholic emotions they inspire. All of the music, especially the NO-DOs, were part of an investigation that I've been doing together with Álvaro Ogalla at the Spanish Film Archive, the place where we first met and the place where we belong. I've mentioned how important discovery and curiosity are to me, and to have had the opportunity to dive into archival materials is one of the most incredible experiences I have ever had, and I still have it sometimes when discovering different materials every time I visit archives, especially the archive in Madrid.

Working at the Spanish Film Archive, I found color documentaries from NO-DO that weren't the official footage customarily associated with Franco opening a hospital or a march-past, but narrated footage of Spanish traditions, values and social issues that needed the aesthetics of orchestrated classical music, such as we hear in The Apostate. It's an unknown music that was specially created for those NO-DO documentaries. I admit that archival materials were a main inspiration for The Apostate and I believe they will be for my future films. To be more precise, I can say that I have grown up in film, not only by watching and making feature films, but also by learning from archival materials with an anthropological point of view.

As with my second film A Useful Life, I worked with the music that best suited the film to bring the right emotions to the surface. With The Apostate, I needed to think of the particular multi-layered portrait I was trying to build. Non-diegetic music was obviously a very important device to guide the audience where I wanted them to be. Both the investigation and the music work are two very special aspects of film making that I enjoy immensely.

Guillén: Several reviewers have referenced the Buñuelisms that have surfaced in The Apostate, most notably José Teodoro, who writes: "The Apostate recalls Buñuel’s cinema in its deadpan approach to perversion and senseless desire, its dearth of delineation between reality and reverie, and its curious mixture of irreverence and almost fetishistic fascination with the rites and institutional mysteries of Catholicism." Such comparisons are the craft and sport of film writers, but was an homage to Luis Buñuel intentional? Within the archival impulse we've just discussed, how much does the work of earlier filmmakers influence your own filmmaking? What movies, let's say, have you placed and cited within The Apostate?

Veiroj: I can't avoid being a filmmaker who adores Buñuel; especially Nazarin (1959), and many others. But when making this film (or any other) I never thought to do something "à la Buñuel" or "à la X director; but, naturally, he is close to me because I think a lot about his films, as I do with the films of Murnau, Bresson, Eustache, Sternberg, Woody Allen, and many other masters whose emotional generosity has made me laugh and cry (and still do).

With The Apostate, which was shot in Spain and leads with religion, tradition, oppression, family, among other issues, I knew that someone watching it could be thinking of Buñuel's influence—and, obviously, I am really happy for that because of my big admiration for him—but, I was not making an homage to him with my own film. I'd like to add that the most influential films in terms of emotions that were close to The Apostate were L'udienza (1972) by Marco Ferreri, Opera Prima (1980) by Fernando Trueba, and another masterpiece by Carlos Saura called La prima Angélica (Cousin Angelica, 1974). These were films that I love and that, in some way, helped me and convinced me that I had to make my film.

Guillén: None of which I've seen, and which now rise rapidly to the top of my film watching queue! Thank you for those recommendations. Clinging tenaciously to Buñuel, however, one particularly Buñuelian moment in The Apostate that I'd like to explore is when Gonzalo is confronted by the "inquisitional" assault of the replicated Bishop, speaking to him first from one window, then from another. Can you speak to that fevered, visually fractured moment?

Veiroj: That sequence had a total of seven minutes of text. I had originally conceived to show it only from one window. At the time of preparing for the shoot and during, the art director of the film (and co-writer) Gonzalo Delgado said that it was maybe too much text for a "close to the ending" sequence, and suggested that we should experience the "crazy" feeling not only with the spoken text but also with the changing windows. I agreed it was only perfect to try it and to cut many of the lines; so we shot it in two versions. It was tough to cut; but, in the end, what really counts is the film's needs and internal balance. Prokofiev's music was my reference for the editing and we were lucky to be able to keep it in the sequence (it's Claudio Abbado's recording of "The Battle on Ice" from Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky, which is wonderful).

In any case, what I tried to show with that sequence was the continuation of the battle between the man and the big institution, and—even more important—Gonzalo's resignation of purpose. I think there's beauty when Gonzalo admits his weakness and there's maybe a trace of abandoning his purpose; in effect, apostatizing from his attempt at apostasy. In any case, I needed Gonzalo's fractured defeat and also the metaphoric dialogue between he and the bishop, because at some point the ending of the film is there. Maybe I wasn't that clear before that the final sequence was, in a way, an inspiration for all of Gonzalo's journey. We had to build the development of the film quite specifically for that great finale. The "windows sequence" was part of that emotional crescendo.

Guillén: At film's end, after jumping through one hoop after another and not obtaining the result he seeks, Gonzalo ends up ripping the page out of the baptismal record that contains his information and stealing it. This transgressive sequence—which understands transgression as a heroic act—is composed through an intricate series of images that I would love for you to unpack a bit. First, his accomplice is Antonio, the young boy he has been tutoring. They see two nuns dressed in white habits climbing stairs (a profoundly incandescent image that thrilled me to the marrow). The theft is committed, and then—honoring the ancient rituals of apostatism—he faithfully adheres to those rituals by walking backwards away from the altar, even as confronted by the angered judgment of the altar boy who has taken a vow of silence. Talk to me about how you constructed this fantastically imagistic, and thoroughly enjoyable, denouement. There's a lot that is rapidly delivered in this sequence. Lay it out for me.

Veiroj: As I said before, that final sequence was very important when writing the script. The day we finally knew what Gonzalo was going to do at the ending of the film—to walk backwards away from the altar as suggested in the traditional ritual, and to do so in complicity with his friend Antonio, the kid, his alter-ego, and to "go back along" his life—we knew the film had to be built up in just such a way as to make that sequence as big as possible. That's also why we used Prokofiev's music there.

To explain more about the narrative order of the film, I need to mention that for Gonzalo the idea of making such a transgressive act is also part of his past. With the complicity of Antonio (who has made his own transgressive act of skipping school, with his teacher no less), I wanted the accent to fall on Gonzalo's regression in the present. The nuns are conducting him, leading him, to his past, to his education, and to this place where he belongs, in a very natural way surrounded by old buildings reminiscent of the middle ages. And the fantasy that emanates from Gonzalo's entering the Church is also a road to his past where he has to walk to the altar and endure difficult obstacles, such as the priest watching him (surveillance), or the chorus singing the same song his cousin sang (the desire), and all of it mixed with the nerve of the present.

When he finds the baptismal register with his family's imprinted name, and his specific record of baptism, he wants desperately to be erased from there. I like the idea of his disappearance from that record as an internal and symbolic consequence, which is the secret of the film: what is the real importance of ritual, symbolic acts? How do they truly affect one's life? How do they answer all the questions we are all the time thinking about as living, thinking creatures? Once Gonzalo is done with his record, he still has to "fight" with bureaucracy and the duel between him and the parishioner means the real and symbolic act of apostatizing from Church, but also from his past. Naturally, all this is my interpretation and I have explained it with the film's code of fantasy that I've used to make the film and, especially, this particular ending sequence.

As synopsized by José Teodoro in IFF Panamá's program capsule: "Sleepy eyed madrileño Gonzalo Tamayo (co-scenarist Álvaro Ogalla) is a dreamer. Though well into his 30s, he has no career, no compulsion to complete his studies and no romantic life to speak of. But he has decided on one clear goal, one ambition to animate him with a sense of purpose: to apostatize from the Catholic Church. Will the Church's archaic bureaucracy prove too labyrinthine for our slacker hero to navigate? Imaginative, sexy, and composed of one elegantly rendered image after another, Uruguayan Federico Vieroj's The Apostate is a sophisticated, Iberian spin on the man-child comedy."

The Apostate is scheduled for two upcoming screenings in the 59th San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF), currently in progress, where Robert Avila notes in his program capsule: "More than a portrait of a man unwilling to fully grow up, The Apostate prompts subtle questions and subversive pleasures in its battle of wills between a would-be renegade and some of the more intimate institutions of social control."

Lead actor / co-writer Álvaro Ogalla is expected to attend these SFIFF screenings and—in anticipation of my own scheduled conversation with Ogalla—I offer my earlier conversation with director Veiroj from IFF Panamá, in turn anticipating the film's North American theatrical release through Breaking Glass Pictures, who acquired the film from FiGaFilms, who have likewise sold The Apostate to a host of territories, including France, Mexico, Brazil, Panama, Argentina and Central America.

As profiled on the SFIFF website: "Born in 1976 in Montevideo, Uruguay, Federico Veiroj began making short films in 1996, first entering festivals with As Follows (2004), a warm and witty coming-of-age tale set amid the filmmaker's own Jewish subculture of Montevideo. His first feature, Acne (2007), premiered in the Directors' Fortnight at Cannes and garnered accolades internationally. His follow-up, A Useful Life (SFIFF 2011), a loving and deftly drawn black-and-white homage to a life in the cinema, won the Coral Grand Prize for Best Film at the Havana Film Festival."

[This conversation is not for the spoiler-wary!!]

* * *

Michael Guillén: In your conversations with Danny Kasman at MUBI's The Notebook and José Teodoro at Film Comment following the film's world premiere at TIFF, you've made it clear that The Apostate is less concerned with a sociopolitical critique of the Catholic Church, and engaged more with the fanciful query of whether or not one can break with the past and, in gist, erase its effects. The presumed answer is no, and this is confirmed by the lovely image where we are shown our madrileño protagonist Gonzalo Tamayo (Álvaro Ogalla) with his shoe laces untied. The camera pans around the room and returns to his untied shoelaces, though now on Gonzalo's boyhood shoes, suggesting that he has not changed since childhood. Is this image a wry comment on the impossibility of the task Gonzalo has set for himself because of the very nature of his character? Can you speak to how in your films the strength and / or purity of image guides narrative? Alternately, how image becomes the script, is the script?

Federico Veiroj: One of my first inspirations was to work on a film based on an impossible task for the main character; let's say, to change something from his own past. But, working on a film and all the fantasy possibilities that it gives me as writer and director, I wanted him to really achieve it. So, with regard to your question about "images that guide narration", I would totally say yes, they do. I knew the ending of the film before having the last version of the script, and found myself in the grip of this very powerful image of Gonzalo that I knew was symbolic and poetic and that was dictating what the narration needed for its ending.

The sequence with the untied shoe laces was something very important for me during the script process because it was exactly that—Gonzalo's own mirror—and for him to even react (with a smile) to this memory was impossible to escape, which I now recognize every time it appears. The shoe lace sequence had to be strong because it was the only moment where we are in touch with a "harsh" or "aggressive" sensation from Gonzalo's past, but it had to be done with poetic simplicity. That's the kind of sequence that I imagine during script writing that is then difficult to shoot because there are many levels of interpretation that I need the audience to feel. Each decision as to the details of such a sequence, no matter how small—the kind of shoes, the trousers, that particular leather jacket he was wearing, and obviously the tiles of the floor (like a life transition)—are all important. I also had in mind the action of his stealing a vinyl single, which for me was the perfect size, because it stood in as a metaphor for his being a child. I guess I felt that his stealing a big LP would have been over-acted or seen as something overly important, and I didn't want that sensation.

Also, I would like to say that some of the music that I knew I was going to use was also an inspiration for some of the film's sequences, providing mental images. That was the case with the mellow classic music from NO-DO (Franco's documentary and newsreels department which made propaganda films, but also "anthropological" documentaries on traditions, on geography and many aspects of Spanish life and social life from 40's to late 70's). I was aware that some parts of this NO-DO music would elicit special feelings of the past that I had to take advantage of.

So, to summarize, I would say that in my case a film is made out of sequences that will be built together with my production designer and art director during the process—two people who I trust a lot—combined with other sequences I've already scripted, which we build as we adapt to shooting conditions. Sometimes there are elements that appear during scouting. In all cases, what guides me is always the mixture of narration, emotion and poetics. I rely and trust in this mixture because I believe in beauty and complicity with the audience. Sometimes deep emotions within certain shots or sequences arise from this combination.

As for the sociopolitical elements you mention, they appear when all the elements of the narration are in place. In any case, I am not naïve. I knew that the political act of a man questioning the ambiance of his present situation in Spain, which—more than criticizing the Catholic Church, I would say, admits to its big influence on every aspect of life—was also going to be a multiple level metaphor.

Guillén: How important was it to add an epistolary layer; i.e., the voiceover of Gonzalo writing letters to his "friend" to explain and / or justify his desire to apostatize? Instead of, let's say, writing an email? Clearly, his desire to apostatize is not just a religious gesture? As you've indicated elsewhere, "To apostatize is not something that you do just with religion. You can do it with your life. It's about embarking on life's journey on your own terms." I'm aware this film is based upon Álvaro Ogalla's personal experience of trying to apostatize; but, have you felt this impulse similarly anywhere within your own life? Or, more specifically, within your filmmaking?

Veiroj: First of all, the idea of Gonzalo writing a letter to a friend was a cinematic and universal device intended to place the film in the world of a fable; a world where all could be fantasy or memory built for a letter narration. An email is not like a physical letter whose imprint will remain (which bears relation to his purpose in the film "to erase" his past) but also I wanted to use correspondence as a means to blur the definition of time, to suggest that this story could be located in our contemporary moment or 30 years ago. I thought a letter provided the perfect mode to combine his confessions and inherent intimacy.

Further, I believe Gonzalo's approach to life operates at a high romantic level, as with Álvaro Ogalla—the actor, co-writer, and inspiration for this story. Álvaro's real-life attempt to apostatize from the Catholic Church in Spain was truly inspiring to me not only because of the peculiar fact of its meaning, but also because I knew in a film it would offer different levels of interpretation. Gonzalo is questioning himself about religion, family, work, and every established institution that reigns and guides our lives. He just wants to live life in his own way. Obviously, there's something completely utopian in such an endeavor, which is the kind of issue or idea that in a film becomes real. For this film, I liked the idea of working on that level of unrealistic purpose because it was the perfect way to narrate Gonzalo's mood and his place in the world.

As for your more personal question towards me and my film making, I can only say that I am a curious person. I let myself go every time I can. I always need new challenges for my work. So far, I haven't had any desire to apostatize from anything because I always do what I want. I can't give up my ambition to make new films or to build new artistic relations while making films; it's beautiful and so gratifying. Without new film challenges I get bored. I always want to dive into new oceans—or, at least, to have my own fantasy of diving into new oceans—and I've never liked to do things that I knew I would be good at, or efforts with predictable results. I guess making films for me is like gambling with aesthetics and emotions, and I like it. And since I also want to discover new music, new art, new films, etc., I can say that I can't give up something that's a passion. So, if no decay of the passion arrives, my plan is to keep doing what gives me pleasure, in film and in every aspect of life. Finally, I believe "to apostatize" from something is simply synonymous with recognizing the importance of it. That's also a way of having a close relation with something—even with something that you want to avoid—because it's consuming your energy and thoughts. Again, I feel that Gonzalo's intention to abandon something which he fully represents is so beautiful because it's his way of expressing how important these issues are for him.

Guillén: There's a bit of masochistic pleasure derived in Gonzalo trying to step away from the Catholic Church using the rules of their bureaucracy. Does this align him with the flagellant witnessed early in the film? Can you speak to the illicit aspect of pleasure that Gonzalo is experiencing by chafing against the Church?

Veiroj: The flagellant could be Gonzalo. He could be any of us who are victims of our beliefs and desires. In any case, the bureaucracy is justified because I wanted Gonzalo to feel the frustration that his case isn't an issue for anyone inside the Institution, nobody cares about him, he is just one more person. That sensation kills him, yet gives him more energy to achieve his task. For Gonzalo, receiving negatives from the Church deepens his desire to apostatize. Admittedly, the difficult process and bureaucracy to apostatize presented in the film is not based in reality but I wanted to exaggerate it because I needed that funny, tender and aggressive tone of Gonzalo's reaction.

When I talked about fantasy before, I meant to say also that I like to explore a character's reaction to things that would only happen within a film on a screen; the symbolism and the emotions are the important aspects here. If we judge Gonzalo by the laws of the real world, we could say his actions are illicit; but, within poetry, aesthetics, and the film world he lives in, his actions are totally licit. In any case, Gonzalo considers what the Catholic Church is doing to him as illicit, causing him unnecessary suffering, even if it's not really that much nor important for other people. The point of view of the film is necessarily Gonzalo's; his codes and laws are the ones I have to follow for the narration. His journey includes some pleasant moments, like recognizing the ring of the priest, recognizing some old religious lessons during his conversation with the bishop, and I am sure his final act is full of pleasure; it's all mixed because he is seeing himself in the past and remembering things, remembering old feelings and bringing them into his present (like his relation with his cousin), and even old complicities (like the one he has with the friend he is writing to). So, yes, I agree with you that Gonzalo may be enjoying some masochistic pleasures.

Guillén: Pursuing how the text of a script can be textural, i.e., layered, your choice of non-diegetic music is essential to shaping and presenting this epistolary fable. You incorporate the music of Hanns Eisler, Federico García Lorca on piano for "Romance Pascual de los Pelegrinitos", and Prokofiev's music for Alexander Nevsky. As much as Gonzalo is trying to break away from the past, the music in your film insists on a historicity that clings affectionately to the past? Explain your purpose in setting up what feels almost like an archival impulse? Certainly, archival practice is present in your unearthing Lorca on the piano and the aforementioned music you've used from the Franco-era NO-DO newsreels. This impulse comports with the archival flourishes in A Useful Life. How do archival practices influence your imagination and scriptwriting?

Veiroj: I thought Lorca's romance was perfect to present Gonzalo's character, because—apart from its beauty—I believe the sound situates the audience in the film, in the fable. And I also knew NO-DO music was going to be used in some parts of the film because of the sweet and melancholic emotions they inspire. All of the music, especially the NO-DOs, were part of an investigation that I've been doing together with Álvaro Ogalla at the Spanish Film Archive, the place where we first met and the place where we belong. I've mentioned how important discovery and curiosity are to me, and to have had the opportunity to dive into archival materials is one of the most incredible experiences I have ever had, and I still have it sometimes when discovering different materials every time I visit archives, especially the archive in Madrid.

Working at the Spanish Film Archive, I found color documentaries from NO-DO that weren't the official footage customarily associated with Franco opening a hospital or a march-past, but narrated footage of Spanish traditions, values and social issues that needed the aesthetics of orchestrated classical music, such as we hear in The Apostate. It's an unknown music that was specially created for those NO-DO documentaries. I admit that archival materials were a main inspiration for The Apostate and I believe they will be for my future films. To be more precise, I can say that I have grown up in film, not only by watching and making feature films, but also by learning from archival materials with an anthropological point of view.

As with my second film A Useful Life, I worked with the music that best suited the film to bring the right emotions to the surface. With The Apostate, I needed to think of the particular multi-layered portrait I was trying to build. Non-diegetic music was obviously a very important device to guide the audience where I wanted them to be. Both the investigation and the music work are two very special aspects of film making that I enjoy immensely.

Guillén: Several reviewers have referenced the Buñuelisms that have surfaced in The Apostate, most notably José Teodoro, who writes: "The Apostate recalls Buñuel’s cinema in its deadpan approach to perversion and senseless desire, its dearth of delineation between reality and reverie, and its curious mixture of irreverence and almost fetishistic fascination with the rites and institutional mysteries of Catholicism." Such comparisons are the craft and sport of film writers, but was an homage to Luis Buñuel intentional? Within the archival impulse we've just discussed, how much does the work of earlier filmmakers influence your own filmmaking? What movies, let's say, have you placed and cited within The Apostate?

Veiroj: I can't avoid being a filmmaker who adores Buñuel; especially Nazarin (1959), and many others. But when making this film (or any other) I never thought to do something "à la Buñuel" or "à la X director; but, naturally, he is close to me because I think a lot about his films, as I do with the films of Murnau, Bresson, Eustache, Sternberg, Woody Allen, and many other masters whose emotional generosity has made me laugh and cry (and still do).

With The Apostate, which was shot in Spain and leads with religion, tradition, oppression, family, among other issues, I knew that someone watching it could be thinking of Buñuel's influence—and, obviously, I am really happy for that because of my big admiration for him—but, I was not making an homage to him with my own film. I'd like to add that the most influential films in terms of emotions that were close to The Apostate were L'udienza (1972) by Marco Ferreri, Opera Prima (1980) by Fernando Trueba, and another masterpiece by Carlos Saura called La prima Angélica (Cousin Angelica, 1974). These were films that I love and that, in some way, helped me and convinced me that I had to make my film.

Guillén: None of which I've seen, and which now rise rapidly to the top of my film watching queue! Thank you for those recommendations. Clinging tenaciously to Buñuel, however, one particularly Buñuelian moment in The Apostate that I'd like to explore is when Gonzalo is confronted by the "inquisitional" assault of the replicated Bishop, speaking to him first from one window, then from another. Can you speak to that fevered, visually fractured moment?

Veiroj: That sequence had a total of seven minutes of text. I had originally conceived to show it only from one window. At the time of preparing for the shoot and during, the art director of the film (and co-writer) Gonzalo Delgado said that it was maybe too much text for a "close to the ending" sequence, and suggested that we should experience the "crazy" feeling not only with the spoken text but also with the changing windows. I agreed it was only perfect to try it and to cut many of the lines; so we shot it in two versions. It was tough to cut; but, in the end, what really counts is the film's needs and internal balance. Prokofiev's music was my reference for the editing and we were lucky to be able to keep it in the sequence (it's Claudio Abbado's recording of "The Battle on Ice" from Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky, which is wonderful).

In any case, what I tried to show with that sequence was the continuation of the battle between the man and the big institution, and—even more important—Gonzalo's resignation of purpose. I think there's beauty when Gonzalo admits his weakness and there's maybe a trace of abandoning his purpose; in effect, apostatizing from his attempt at apostasy. In any case, I needed Gonzalo's fractured defeat and also the metaphoric dialogue between he and the bishop, because at some point the ending of the film is there. Maybe I wasn't that clear before that the final sequence was, in a way, an inspiration for all of Gonzalo's journey. We had to build the development of the film quite specifically for that great finale. The "windows sequence" was part of that emotional crescendo.

Guillén: At film's end, after jumping through one hoop after another and not obtaining the result he seeks, Gonzalo ends up ripping the page out of the baptismal record that contains his information and stealing it. This transgressive sequence—which understands transgression as a heroic act—is composed through an intricate series of images that I would love for you to unpack a bit. First, his accomplice is Antonio, the young boy he has been tutoring. They see two nuns dressed in white habits climbing stairs (a profoundly incandescent image that thrilled me to the marrow). The theft is committed, and then—honoring the ancient rituals of apostatism—he faithfully adheres to those rituals by walking backwards away from the altar, even as confronted by the angered judgment of the altar boy who has taken a vow of silence. Talk to me about how you constructed this fantastically imagistic, and thoroughly enjoyable, denouement. There's a lot that is rapidly delivered in this sequence. Lay it out for me.

Veiroj: As I said before, that final sequence was very important when writing the script. The day we finally knew what Gonzalo was going to do at the ending of the film—to walk backwards away from the altar as suggested in the traditional ritual, and to do so in complicity with his friend Antonio, the kid, his alter-ego, and to "go back along" his life—we knew the film had to be built up in just such a way as to make that sequence as big as possible. That's also why we used Prokofiev's music there.

To explain more about the narrative order of the film, I need to mention that for Gonzalo the idea of making such a transgressive act is also part of his past. With the complicity of Antonio (who has made his own transgressive act of skipping school, with his teacher no less), I wanted the accent to fall on Gonzalo's regression in the present. The nuns are conducting him, leading him, to his past, to his education, and to this place where he belongs, in a very natural way surrounded by old buildings reminiscent of the middle ages. And the fantasy that emanates from Gonzalo's entering the Church is also a road to his past where he has to walk to the altar and endure difficult obstacles, such as the priest watching him (surveillance), or the chorus singing the same song his cousin sang (the desire), and all of it mixed with the nerve of the present.

When he finds the baptismal register with his family's imprinted name, and his specific record of baptism, he wants desperately to be erased from there. I like the idea of his disappearance from that record as an internal and symbolic consequence, which is the secret of the film: what is the real importance of ritual, symbolic acts? How do they truly affect one's life? How do they answer all the questions we are all the time thinking about as living, thinking creatures? Once Gonzalo is done with his record, he still has to "fight" with bureaucracy and the duel between him and the parishioner means the real and symbolic act of apostatizing from Church, but also from his past. Naturally, all this is my interpretation and I have explained it with the film's code of fantasy that I've used to make the film and, especially, this particular ending sequence.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

SFIFF59—The Evening Class Interview With Rachel Rosen, Director of Programming

Short of a decade ago, in celebration of the 50th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF), Russell Merritt conducted interviews for the San Francisco Film Society's Oral History Project, which included a sprawling 78-page conversation with SFIFF head programmer Rachel Rosen, fascinating for its description of her early years at the San Francisco Film Society (SFFS), how its infrastructure was organized in the early '90s, and tasty reminisces of her colleagues and peers. At the time Rosen and Merritt conducted this interview, she was programming for the Los Angeles International Film Festival. Ever since returning to SFFS in 2009, I have been meaning to sit down to talk with her. Earlier this year we met at Mission Chinese to share a meal and catch up.

Michael Guillén: In your interview with Russell Merritt for the San Francisco Film Society's Oral History Project you said, "A film festival is a dialogue between the programmer and the audience." I'd like to pursue the idea of programmers' relationships with their audiences and who in the world might be the "New Audience"?

Rachel Rosen: Good question.

Guillén: So let's begin by setting some definitions. Do you distinguish between programming and curating and, if so, where do you identify yourself within that spectrum?

Rosen: I have not thought at all about what the differences between those two things might be. Curating is the word you use in the art world and programming the word you use in the film world. That's the main difference. The missions of a film festival are slightly different than the mission of an art gallery or museum, which might be what you're actually asking me? Meaning, in the art world the idea of curation is that you have an opinion, you're making a statement by what you choose, and people can follow it or not. Programming for a film festival involves creating a sense of community so it involves acknowledging that you have an audience and that you're programming to an audience. A museum person would say, "I'm programming to an audience of international art connoisseurs," whereas many film festivals are programming beyond the communities they're in or even the audience that comes to the festival; but, they're still programming in a way that acknowledges audience a little bit more than art purists.

Guillén: And isn't your relationship with audience more direct as a film programmer? You often hear immediate feedback from your SFIFF audiences? They don't just sit passively and watch. They tell you what they like, what they don't like, what they're excited about that you've included in your program and what has disappointed them to not find included. So I guess when I'm linking the curatorial to programming, it's in this sense: how you rudder, how you navigate, all these different constituencies and their likes and dislikes, negotiated through your own taste. It strikes me that each member of the SFIFF programming team have distinguished tastes, often variant, but frequently in consensus. For example, in the 10 years I've been attending SFIFF, it's become clear how important the documentary is to your festival. Is that because of you and your interest in documentaries?

Rosen: Again, with any festival there are at least three things going on. One is just the history. SFIFF has an international history, a very broad history. Of course, there are individual preferences—preference is the wrong word—areas of specific interest and influences for each programmer. My background is in documentary. I love all types of films but I'm super attracted to nonfiction storytelling. Then, whatever the organization has decided its mission and direction should be.

Guillén: That's what I was getting at. You started with SFIFF in 1991 when you were making Serious Weather, your documentary short on tornado chasers that served as your Masters Thesis at Stanford, and then you slowly winnowed your way into the San Francisco Film Society (SFFS). How many SFFS Directors have you worked under while programming SFIFF?

Rosen: Executive Directors I'm not sure I can even count. Peter Scarlett was both the Executive Director and the Artistic Director when I started. At a certain point, the Board brought in other Executive Directors like Barbara Stone, Amy Leissner, Roxanne Captor-Messina, and then I went away. Then there was Graham Leggat, Steve Jenkins as an Interim, then Bingham Ray, then Melanie Blum as an interim, then Ted Hope. Let's say, officially eight.

Guillén: Wow, that's quite a history. Is the programming that you and your team do for SFIFF delimited in any way by civic pressures, whether political or financial? Do you get any funding from the City?

Rosen: I wish. That's a more European concept, right? And it's got its great points and its bad points. All you have to do is take a look at what's going on in Busan to see what the nadir of local civic support for a film festival can turn into. We get some limited support from the Film Commission….

Guillén: But not enough that they can in any way tell you what to do or what to program?

Rosen: For U.S. festivals, that kind of pressure tends to come more from sponsors. That's an accommodation that a lot of festivals have to make.

Guillén: After a stint away working in L.A., you came back to SFIFF in 2009 when Graham Leggat was at the helm. As I had only been focusing on film since 2006, the excited news that you were returning caught my interest.

Rosen: [Laughing] Like, "Who is this lady? And what difference does it make?"

Guillén: Well, I wanted to know what you had done in the past that had made people so happy that they were excited upon your return. This was about the time that I was getting to know the Bay Area programmers and starting to distinguish their curatorial styles. Again, I say curatorial in terms of decisions informed by critical practice. There are hundreds and hundreds of movies that can be chosen at any given time for a film festival, but it's your job to decide—based, as you said earlier, on the audience you know—which film they will take a chance on, appreciate, follow up on from—let's say—earlier films you have shown by a certain filmmaker at earlier editions. It just so happened that it was the programming team you headed under Graham Leggat that became the team I could observe. Over the years you've all developed your styles, your choices. I began to know which films Linda Blackaby would promote. I grew fond of Rod Armstrong's genre programming. But it was Sean Uyehara's signature that became most pronounced for me for actively courting a new youthful audience. I don't mean to be ageist about it—it wasn't just an outreach to youth—but, he actively encouraged a new audience that looked at and applied film in different ways, either through multi-media or social setting. His teamings of silent film with contemporary musicians were engaging experiences that sometimes worked, sometimes didn't, but often worked exceptionally well—The Denque Fever event remains one of my top highlights of all my years attending SFIFF—so I'm curious, with his moving on to his new position with the Headlands, what will happen to that dimension at the festival?

Rosen: We'll hire someone who has those abilities in programming, events and partnerships. Sean did a lot of programs that were more than just the film on the screen. Some had a performative element, the events part, but he also really drew on facets of the community, whether the artistic community or other organizations, and was very in tune with what was happening in galleries and dance, resulting in partnerships that made for more individualist programming.

Guillén: Having grown up with your audience, do you think that such performative and partnership-oriented programming is more desired to offset, let's say, what's come to pass with increased access to home entertainment? Is the event aspect of film festival programming becoming a requisite value added?

Rosen: I don't know if it's requisite. I believed in the excitement of event programming before the advent of the small screen age or the second small screen age, whatever we want to call it. The first in the official string of music and film programming that we did was before I left to Los Angeles; we did a Tom Verlaine program with some avant garde shorts and then the next year Doug Jones and I, mostly Doug, put together the Yo Lo Tengo event. Being there and experiencing that is, for me, a more personal charge. I'm not pretending I know what the answer is to keeping younger audiences interested in traditional film—it's probably the problem I'm most interested in figuring out—but, what I've seen and come to believe is that along with this "I can get anything I want anytime I want on my home screen" there are people who will buy into special events, not necessarily even film events, they can be restaurant pop-ups, and are all a part of a popular phase where people feel they are getting a unique experience. Creating those kinds of experiences can bring audiences to films that wouldn't get an audience without them.

Guillén: Do you have any way of gauging audience demographics? Do you have someone standing there counting how many redheads there are in the crowd?

Rosen: We've done some surveys over the years but we haven't done one recently. With anyone who buys a ticket online, we can generally gauge where in the area they come from, so we can do geographics. But other surveys we haven't done for a couple of years.

Guillén: The very nature of cinephilia seems to have morphed in the past decade or so, evolving from individual if eccentric pursuits of rare films to social outings with others to observe event-films. How is your programming affected by this increased social element of viewing film?