Currently screening at the Pacific Film Archive through December 20, 2009 is a 14-film tribute "Otto Preminger: Anatomy of a Movie", curated by Steve Seid. The first three entries in the series—Laura (1944), Fallen Angel (1945) and Daisy Kenyon (1947)—constitute the heft of Otto Preminger's collaboration with actor Dana Andrews, with the exception of Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), which has not been included in the series (though—incidentally enough—it reunited the Laura duo: Andrews and Gene Tierney).

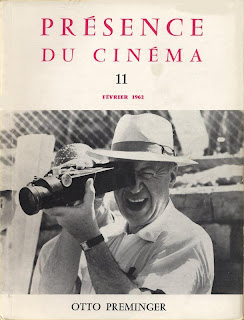

Currently screening at the Pacific Film Archive through December 20, 2009 is a 14-film tribute "Otto Preminger: Anatomy of a Movie", curated by Steve Seid. The first three entries in the series—Laura (1944), Fallen Angel (1945) and Daisy Kenyon (1947)—constitute the heft of Otto Preminger's collaboration with actor Dana Andrews, with the exception of Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), which has not been included in the series (though—incidentally enough—it reunited the Laura duo: Andrews and Gene Tierney). So much has been written about Otto Preminger that it seems foolish to reiterate what's already been stated many times over. Within immediate parameters, however, Steve Seid has synopsized: "As legend would have it, Otto Preminger was a bald-headed baddy scolding helpless actors about flaws in their performance—the tyrant on the set. But Preminger's films, some thirty-seven in all, bear no sign of this heated temperament, instead sharing a muted detachment that ironically excites our own engagement with his complex characters. …Preminger promoted a cool take on human nature that simultaneously savored cinema's expansive visual spaces; over time his eloquent way with the camera grew complex and sensuous. The willful director's insistence on artistic autonomy compelled him to become one of the first champions of independent film."

So much has been written about Otto Preminger that it seems foolish to reiterate what's already been stated many times over. Within immediate parameters, however, Steve Seid has synopsized: "As legend would have it, Otto Preminger was a bald-headed baddy scolding helpless actors about flaws in their performance—the tyrant on the set. But Preminger's films, some thirty-seven in all, bear no sign of this heated temperament, instead sharing a muted detachment that ironically excites our own engagement with his complex characters. …Preminger promoted a cool take on human nature that simultaneously savored cinema's expansive visual spaces; over time his eloquent way with the camera grew complex and sensuous. The willful director's insistence on artistic autonomy compelled him to become one of the first champions of independent film."There are, of course, the career overviews offered by James Quandt, Thomas Gale, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Tag Gallagher and Chris Fujiwara. James Quandt cleverly finesses the alphabet to review Preminger's career from autocrat to Zanuck at the Cinémathèque Ontario website; Thomas Gale's entry on Preminger for The Encyclopedia of World Biography can be accessed at Highbeam Research Library; Jonathan Rosenbaum's essay "The Preminger Enigma" is at The Chicago Reader website; Tag Gallagher's Film International essay on Preminger's "heroic" films can also be accessed at Highbeam Research Library; and Chris Fujiwara's nuanced profile for the Great Directors database can be found at Senses of Cinema.

Fujiwara, in fact, has provided the most recent biography on Preminger: The World and Its Double (Faber & Faber, 2008), published close on the heels of Foster Hirsch's own notable study Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King (Knopf/Random House, 2007). Earlier, in his Film International DVD review "4 x Otto Preminger" (May 2004, Vol. 2, Issue 3), Fujiwara convincingly contested the oft-stated ascription of "film noir" to the suite of Preminger films that include Laura, Fallen Angel, Where The Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool (1950), The Thirteenth Letter (1951), and Angel Face (1952). Fujiwara argued against this received wisdom: "It is pertinent to remember that Preminger repudiated this term, as far as his own work was concerned. Seeing these films as 'films noirs' is no more illuminating and no less destructive of any understanding of what the films are doing than seeing River of No Return (1954) as a Western; Carmen Jones (1954) as a musical; or In Harms Way (1965) as a war film. Preminger's films are absolutely heedless of genre, and Preminger never makes the slightest effort to adapt his style to generic norms."

Fujiwara, in fact, has provided the most recent biography on Preminger: The World and Its Double (Faber & Faber, 2008), published close on the heels of Foster Hirsch's own notable study Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King (Knopf/Random House, 2007). Earlier, in his Film International DVD review "4 x Otto Preminger" (May 2004, Vol. 2, Issue 3), Fujiwara convincingly contested the oft-stated ascription of "film noir" to the suite of Preminger films that include Laura, Fallen Angel, Where The Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool (1950), The Thirteenth Letter (1951), and Angel Face (1952). Fujiwara argued against this received wisdom: "It is pertinent to remember that Preminger repudiated this term, as far as his own work was concerned. Seeing these films as 'films noirs' is no more illuminating and no less destructive of any understanding of what the films are doing than seeing River of No Return (1954) as a Western; Carmen Jones (1954) as a musical; or In Harms Way (1965) as a war film. Preminger's films are absolutely heedless of genre, and Preminger never makes the slightest effort to adapt his style to generic norms."Fujiwara further pointed out that films like Laura, Fallen Angel, and Whirlpool "depart radically from the 'film noir' pattern … characterized by scheming femmes fatales, trapped and desperate male protagonists, and unhappy endings."

Laura (1944)

Dana Andrews—a popular leading man in the 1940s—has never been one of my favorite actors, though his brooding performance as the smitten detective Mark McPherson is unquestionably one of his best. In her profile of Andrews at Bright Lights Film Journal, Imogen Sarah Smith has written: "Dana Andrews, with his naturally tamped-down style and his gift for ambivalence, was an ideal leading man for Preminger. Apart from The Best Years of Our Lives, Andrews' four films with Preminger … were the peak of his career, and they gave him his most complex and compelling roles."

Dana Andrews—a popular leading man in the 1940s—has never been one of my favorite actors, though his brooding performance as the smitten detective Mark McPherson is unquestionably one of his best. In her profile of Andrews at Bright Lights Film Journal, Imogen Sarah Smith has written: "Dana Andrews, with his naturally tamped-down style and his gift for ambivalence, was an ideal leading man for Preminger. Apart from The Best Years of Our Lives, Andrews' four films with Preminger … were the peak of his career, and they gave him his most complex and compelling roles." In "Acting Like Children", his 1958 interview with the Columbia University Oral History Research Office, Andrews admitted: "People very often say to me that Laura was my first picture. Well, it's the first one they saw, which is why they think that." His recollections of the behind-the-scenes intrigues that shaped Laura—specifically his characterization of Detective McPherson—details how then-producer Preminger deviously wrested directorial control away from Rouben Mamoulian (the film's original director) by strategically aligning himself with studio head Darryl F. Zanuck. Andrews opines: "I think Mr. Preminger wanted to be a producer-director." Andrews also recounts how he and Preminger disagreed on a point of direction and stared each other down in stony silence for hours, "acting like children."

In "Acting Like Children", his 1958 interview with the Columbia University Oral History Research Office, Andrews admitted: "People very often say to me that Laura was my first picture. Well, it's the first one they saw, which is why they think that." His recollections of the behind-the-scenes intrigues that shaped Laura—specifically his characterization of Detective McPherson—details how then-producer Preminger deviously wrested directorial control away from Rouben Mamoulian (the film's original director) by strategically aligning himself with studio head Darryl F. Zanuck. Andrews opines: "I think Mr. Preminger wanted to be a producer-director." Andrews also recounts how he and Preminger disagreed on a point of direction and stared each other down in stony silence for hours, "acting like children." Allegedly, Zanuck's dissatisfaction with Rouben Mamoulian's interpretation of Detective McPherson as an Ivy-league criminologist clashed with Zanuck's preference for a tough "right-down-the-alley type of detective" more familiar to audiences. Preminger's willingness to cater to Zanuck's vision on such a major issue distracted the studio head from his noted objection to the casting of Clifton Webb in the role of Waldo Lydecker. Andrews recollected that Laura was Webb's first motion picture. "He'd been under contract to MGM for 18 months and never done a foot of film—never had seen himself on the screen." According to David Boxwell at Bright Lights Film Journal, the homophobic Zanuck was initially displeased with Webb's portrayal of Lydecker as an effete and waspish socialite; however, Preminger convinced Zanuck that such effeminacy suited the character and provided comic contrast to the traditionally masculine Andrews.

Allegedly, Zanuck's dissatisfaction with Rouben Mamoulian's interpretation of Detective McPherson as an Ivy-league criminologist clashed with Zanuck's preference for a tough "right-down-the-alley type of detective" more familiar to audiences. Preminger's willingness to cater to Zanuck's vision on such a major issue distracted the studio head from his noted objection to the casting of Clifton Webb in the role of Waldo Lydecker. Andrews recollected that Laura was Webb's first motion picture. "He'd been under contract to MGM for 18 months and never done a foot of film—never had seen himself on the screen." According to David Boxwell at Bright Lights Film Journal, the homophobic Zanuck was initially displeased with Webb's portrayal of Lydecker as an effete and waspish socialite; however, Preminger convinced Zanuck that such effeminacy suited the character and provided comic contrast to the traditionally masculine Andrews. Originally, as Eddie Muller intimated in his Noir City introduction of Hangover Square (1945), Mamoulian had wanted Laird Cregar for the role of Lydecker; but, Preminger worried that Cregar—who had gained notoriety playing the sinister role of Jack the Ripper in The Lodger (1944)—would lead the audience to become suspicious of Lydecker earlier than necessary. When Cregar died of a heart attack after a drastic attempt to lose weight for the role, Preminger brought in Clifton Webb. It's now nearly inconceivable that anyone else could deliver Lydecker's vicious bon mots more stingingly, which to this day delight audiences with their unfettered bitchiness. "The voice alone would have carried the performance: the tone of a courtly buzz saw, the razor diction dining on consonants as if they were truffled squab," Richard Barrios has written in Screened Out: Playing Gay In Hollywood From Edison to Stonewall (Routledge, 2003:202).

Originally, as Eddie Muller intimated in his Noir City introduction of Hangover Square (1945), Mamoulian had wanted Laird Cregar for the role of Lydecker; but, Preminger worried that Cregar—who had gained notoriety playing the sinister role of Jack the Ripper in The Lodger (1944)—would lead the audience to become suspicious of Lydecker earlier than necessary. When Cregar died of a heart attack after a drastic attempt to lose weight for the role, Preminger brought in Clifton Webb. It's now nearly inconceivable that anyone else could deliver Lydecker's vicious bon mots more stingingly, which to this day delight audiences with their unfettered bitchiness. "The voice alone would have carried the performance: the tone of a courtly buzz saw, the razor diction dining on consonants as if they were truffled squab," Richard Barrios has written in Screened Out: Playing Gay In Hollywood From Edison to Stonewall (Routledge, 2003:202).Despite Lydecker's homosexuality having been removed from the script early on (though, as Barrios continues, "the rewritten character's bouts of hetero-jealousy [sit] oddly upon Webb's epicene deportment"), Clifton Webb's performance of Waldo Lydecker has gone down in cinema history as one of the great gay characters on film; the epitome of the "mannered, high-gloss style" that David Thomson pointedly identifies in his recent book The Moment of Psycho (Perseus Books 2009, p. 43) as a "code for homosexuality" in American films of the '30s, '40s and '50s.

In retrospect, Preminger's direction of both Andrews and Webb—and the characterizations they finally settled upon—served to manifest a tension essential to Laura's suspense. As Imogen Sarah Smith has correctly perceived in her Bright Lights Film Journal profile: "Preminger was right about McPherson. Not playing him as hard-boiled not only destroys the comedy in his interactions with Laura's friends, it eliminates the tension within Mark's character as he begins to feel and behave in ways no one would expect of a standard-issue tough cop. Laura introduces the essential Dana Andrews character: the Average Joe with unexpected complications. It also demonstrates the Preminger Paradox: the director was a notorious tyrant, prone to tantrums and sadism often directed at the most vulnerable of his actors, yet the keynote of his films was tolerance for ambiguity. Ensembles in shades of gray, full of subtle, tamped-down performances, his films never turn on a simple axis of good and evil but listen to many voices and allow each some degree of persuasiveness."

In retrospect, Preminger's direction of both Andrews and Webb—and the characterizations they finally settled upon—served to manifest a tension essential to Laura's suspense. As Imogen Sarah Smith has correctly perceived in her Bright Lights Film Journal profile: "Preminger was right about McPherson. Not playing him as hard-boiled not only destroys the comedy in his interactions with Laura's friends, it eliminates the tension within Mark's character as he begins to feel and behave in ways no one would expect of a standard-issue tough cop. Laura introduces the essential Dana Andrews character: the Average Joe with unexpected complications. It also demonstrates the Preminger Paradox: the director was a notorious tyrant, prone to tantrums and sadism often directed at the most vulnerable of his actors, yet the keynote of his films was tolerance for ambiguity. Ensembles in shades of gray, full of subtle, tamped-down performances, his films never turn on a simple axis of good and evil but listen to many voices and allow each some degree of persuasiveness." Smith evokes the "long, wordless sequence, followed by Preminger's fluidly tracking camera" wherein "McPherson prowls around Laura's apartment, ostensibly looking for clues but really indulging his insatiable desire for communion with the dead woman. Reading her letters and her private journal isn't enough; he opens her closets, fingers her silky handkerchiefs (obvious Hays Code stand-ins for her unmentionables), and sniffs her perfume. He doesn't linger over things sensually; he fidgets brusquely, irritated by his own romantic yearning. He heads for the liquor cabinet and gulps Scotch while gazing at Laura's portrait. He snarls at Waldo Lydecker, who hits the nail on the head when he sneers, 'I wonder you don't come here like a suitor with flowers and a box of candy.' Mark couldn't, or wouldn't, openly admit his own feelings: cops just don't find themselves in the grip of morbid, perfumed obsession with dames who have been bumped off. But he knows that Waldo is right, hence his seething, brooding restlessness. Alone again, he plants himself in front of the portrait and nurses a drink until he falls into a stupor."

Smith evokes the "long, wordless sequence, followed by Preminger's fluidly tracking camera" wherein "McPherson prowls around Laura's apartment, ostensibly looking for clues but really indulging his insatiable desire for communion with the dead woman. Reading her letters and her private journal isn't enough; he opens her closets, fingers her silky handkerchiefs (obvious Hays Code stand-ins for her unmentionables), and sniffs her perfume. He doesn't linger over things sensually; he fidgets brusquely, irritated by his own romantic yearning. He heads for the liquor cabinet and gulps Scotch while gazing at Laura's portrait. He snarls at Waldo Lydecker, who hits the nail on the head when he sneers, 'I wonder you don't come here like a suitor with flowers and a box of candy.' Mark couldn't, or wouldn't, openly admit his own feelings: cops just don't find themselves in the grip of morbid, perfumed obsession with dames who have been bumped off. But he knows that Waldo is right, hence his seething, brooding restlessness. Alone again, he plants himself in front of the portrait and nurses a drink until he falls into a stupor." This pivotal scene—underscored by David Raskin's haunting theme (with belated lyrics by Johnny Mercer)—is seductive in its gravitational allure. It's one of my favorite scenes in Laura and one of my favorite scenes in film altogether. Rarely has desire for what is absent been so sensuously embodied in an imagined presence, save perhaps Portrait of Jennie (1948). It reminds me of what poet Mark Doty once wrote in his equally haunting study Still Life With Oysters and Lemon (Beacon Press 2001:3-4): "I have fallen in love with a painting. Though that phrase doesn't seem to suffice, not really—[rather, it's] that I have been drawn into the orbit of a painting, having allowed myself to be pulled into its sphere by casual attraction deepening to something more compelling. I have felt the energy and the life of the painting's will; I have been held there, instructed. And the overall effect, the result of looking and looking into its brimming surface as long as I could look, is love, by which I mean a sense of tenderness towards experience, of being held within an intimacy with the things of the world."

This pivotal scene—underscored by David Raskin's haunting theme (with belated lyrics by Johnny Mercer)—is seductive in its gravitational allure. It's one of my favorite scenes in Laura and one of my favorite scenes in film altogether. Rarely has desire for what is absent been so sensuously embodied in an imagined presence, save perhaps Portrait of Jennie (1948). It reminds me of what poet Mark Doty once wrote in his equally haunting study Still Life With Oysters and Lemon (Beacon Press 2001:3-4): "I have fallen in love with a painting. Though that phrase doesn't seem to suffice, not really—[rather, it's] that I have been drawn into the orbit of a painting, having allowed myself to be pulled into its sphere by casual attraction deepening to something more compelling. I have felt the energy and the life of the painting's will; I have been held there, instructed. And the overall effect, the result of looking and looking into its brimming surface as long as I could look, is love, by which I mean a sense of tenderness towards experience, of being held within an intimacy with the things of the world."Cross-published on Twitch.