When I consider the term "eccentric", I think of the orbits of comets, irregularly-shaped pearls, and the conversation I had with my ex-employer when our relationship began to deteriorate and she complained that my "eccentricity credits had run out." Four years later, I have to ask: "Can eccentricity credits ever really run out?" Or more importantly, should they? I think not! And I consider it highly irregular of her to think so.

When I consider the term "eccentric", I think of the orbits of comets, irregularly-shaped pearls, and the conversation I had with my ex-employer when our relationship began to deteriorate and she complained that my "eccentricity credits had run out." Four years later, I have to ask: "Can eccentricity credits ever really run out?" Or more importantly, should they? I think not! And I consider it highly irregular of her to think so.Now—due to the programming efforts of Pacific Film Archive's Steve Seid—to the term "eccentric" I associate cinema. "Eccentric Cinema: Overlooked Oddities and Ecstasies, 1963–82", currently running at PFA through August 27, 2009, states Seid's case: "Eccentric cinema thrives on pictorial surplus, the indulgent storyline, and a contempt for the customary, all resting upon the sagging shoulders of extravagant skill. This is no trash cinema, with its cheesy topics, uninvited camp, and joyful ineptitude. Instead, eccentricity might show itself as a dizzy disregard for the stuff of genre and style, or in the pursuit of ungainly ideas that consign a filmmaker to the status of outsider. Often the eccentric surfaces early in a career, before the artist has lost the exuberance of youth or succumbed to the timidity of the marketplace."

With "trashy" cinema now popularized and relegated to the academic footnote, eccentric cinema comes along to stake a claim on the side margins, clinging fiercely to that empty space for fear of slipping down to the bottom of the page for enumerated consideration. Steve Seid has constructed a veritable "Noah's Ark of oddities", shepherding two of each kind of subgenre into his confabulated series: "a pair of Westerns in which heroism has gone south; two postapocalyptic tales where virility prevails; dual vampiric accounts that suck, differently; a brace of psychological breakdowns involving mawkish men with issues; a duet of rock musicals that strike discord with their delivery; and a twosome of fantasies about that elusive thing called love, one with a mermaid, the other with a monomaniac." Seid concludes: "Genre meltdowns, faulty parables, self-detonating critiques: these films may not be trash cinema, but they are definitely worth recycling."

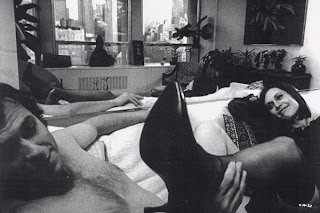

With "trashy" cinema now popularized and relegated to the academic footnote, eccentric cinema comes along to stake a claim on the side margins, clinging fiercely to that empty space for fear of slipping down to the bottom of the page for enumerated consideration. Steve Seid has constructed a veritable "Noah's Ark of oddities", shepherding two of each kind of subgenre into his confabulated series: "a pair of Westerns in which heroism has gone south; two postapocalyptic tales where virility prevails; dual vampiric accounts that suck, differently; a brace of psychological breakdowns involving mawkish men with issues; a duet of rock musicals that strike discord with their delivery; and a twosome of fantasies about that elusive thing called love, one with a mermaid, the other with a monomaniac." Seid concludes: "Genre meltdowns, faulty parables, self-detonating critiques: these films may not be trash cinema, but they are definitely worth recycling." I caught the series' first installment Coming Apart (1969) where Rip Torn—in his first starring role as one of the "mawkish men with issues"—"earns his moniker." As Seid writes: "He's ripped and torn and on the way to a big, bawdy breakdown in [Milton Moses] Ginsberg's voyeuristic sex romp. Torn plays Joe Glazer, a psychiatrist whose pent-up proclivities find him moving into a studio apartment in the building where his former mistress (Viveca Lindfors) lives. Once there, he begins a seduction 'experiment' that involves a one-way mirror, a couch, and a procession of sexually apt young women. Succumbing to his own predatory appetite, Joe becomes horrified by the emptiness of his conquests. His comeuppance arrives in the person of a former patient, played by a desperately determined Sally Kirkland, who deflates his fragile fantasy. Scorned at the time of its release, this prodding pic may have captured the painful collapse of sixties counterculture with too much provocation. Filmed entirely from behind the mirror, Ginsberg's frisky fete makes us voyeurs at our own love-in. The eyes have it."

I caught the series' first installment Coming Apart (1969) where Rip Torn—in his first starring role as one of the "mawkish men with issues"—"earns his moniker." As Seid writes: "He's ripped and torn and on the way to a big, bawdy breakdown in [Milton Moses] Ginsberg's voyeuristic sex romp. Torn plays Joe Glazer, a psychiatrist whose pent-up proclivities find him moving into a studio apartment in the building where his former mistress (Viveca Lindfors) lives. Once there, he begins a seduction 'experiment' that involves a one-way mirror, a couch, and a procession of sexually apt young women. Succumbing to his own predatory appetite, Joe becomes horrified by the emptiness of his conquests. His comeuppance arrives in the person of a former patient, played by a desperately determined Sally Kirkland, who deflates his fragile fantasy. Scorned at the time of its release, this prodding pic may have captured the painful collapse of sixties counterculture with too much provocation. Filmed entirely from behind the mirror, Ginsberg's frisky fete makes us voyeurs at our own love-in. The eyes have it." Coming Apart strips away the pleasure of voyeurism to reveal its addictive implication. Seid confirmed this in an email when I complimented him on his introduction: "What I was getting at but never managed to articulate about Coming Apart has to do with the reception of the film. I was referring to the voyeurism as an important theme. What I think riled many critics is not the sometimes gratuitous sexuality, nor its parade of neurotic nudes, but the fact that the film continually implicated the viewer. It seems to me that taboo things fare better when they just appeal to our base instincts. Everyone agrees that we have base instincts and base instincts indulged act as social release valves. But if you somehow complicate the use of base instincts, if you turn the impulse into a critique of abuse or power, then those instincts no longer function as release valves, but as subterfuge. In this context, the baser things critique their own source in culture. They become subversive. Coming Apart continually turns the mechanism of Rip Torn's voyeurism back on the audience. There is that great moment when he is remorseful that he can't turn off the machine even though he knows he must, that he's being self-destructive. But his compulsion is greater (at that moment) than his despair. And we as viewers can't stop watching him and his exploitation. That's just part of the film's intent, but it's pretty good stuff."

Coming Apart strips away the pleasure of voyeurism to reveal its addictive implication. Seid confirmed this in an email when I complimented him on his introduction: "What I was getting at but never managed to articulate about Coming Apart has to do with the reception of the film. I was referring to the voyeurism as an important theme. What I think riled many critics is not the sometimes gratuitous sexuality, nor its parade of neurotic nudes, but the fact that the film continually implicated the viewer. It seems to me that taboo things fare better when they just appeal to our base instincts. Everyone agrees that we have base instincts and base instincts indulged act as social release valves. But if you somehow complicate the use of base instincts, if you turn the impulse into a critique of abuse or power, then those instincts no longer function as release valves, but as subterfuge. In this context, the baser things critique their own source in culture. They become subversive. Coming Apart continually turns the mechanism of Rip Torn's voyeurism back on the audience. There is that great moment when he is remorseful that he can't turn off the machine even though he knows he must, that he's being self-destructive. But his compulsion is greater (at that moment) than his despair. And we as viewers can't stop watching him and his exploitation. That's just part of the film's intent, but it's pretty good stuff." When Coming Apart was first released in 1969, Time characterized Joe's "experiment" as "a voyeur's version of Candid Camera. The analyst analyzed, the schizoid psyche caught flagrante delicto—it is a notion worthy of Pirandello or Antonioni. And totally beyond Milton Moses Ginsberg…."

When Coming Apart was first released in 1969, Time characterized Joe's "experiment" as "a voyeur's version of Candid Camera. The analyst analyzed, the schizoid psyche caught flagrante delicto—it is a notion worthy of Pirandello or Antonioni. And totally beyond Milton Moses Ginsberg…."When Time complained that the transvestite character was "presumably added to assure the widest possible audience appeal", they were being condescending of course, though time lends a piquant reading to Joe's latent homosexual impulses, suspected by his peers. Is Coming Apart a misogynistic film? Probably not, though the demarcation is slight. Is Joe a misogynist? Perhaps a self-loathing misogynist: "I hate men, they degrade you for being a female." Is Coming Apart a homophobic film for the way Joe treats the transvestite when his anatomical secret is revealed? Perhaps only in the sense that misogyny has long been credited as the seat of homophobia. Contrary to Time's smarmy insinuation, there is appeal in recovering this transvestite character in '60s cinema for no other reason than it reinforces the project of archiving representation. He's a character consigned to the ranks of some of the minor players in Midnight Cowboy. M.M. Ginsberg has left a time capsule that—no matter how you judge the container—contains some far out stuff from the sixties; perhaps most notably an uncomfortable record of its capsized idealism.

At The New York Times, Vincent Canby noted that—though Rip Torn's character moves the camera several times—"for most of Coming Apart the camera remains focused on the couch and the mirror. As a result, almost every image is half real, half the reverse of reality, which is, I suppose, a legitimate cinematic equivalent of the way one automatically supplements reality with fantasy in conscious experience."

At The New York Times, Vincent Canby noted that—though Rip Torn's character moves the camera several times—"for most of Coming Apart the camera remains focused on the couch and the mirror. As a result, almost every image is half real, half the reverse of reality, which is, I suppose, a legitimate cinematic equivalent of the way one automatically supplements reality with fantasy in conscious experience."Canby assessed fairly: "The autobiographical film form is ambitious and offers lots of opportunities for fancy effects that try to tell us we're watching captured reality. There are blackouts, when the sound is on and the camera is not; 'whiteouts,' and representations of film leaders, when the camera seems to be running out of film; 'flash frames,' or subliminal shots, when Joe flicks the camera on and off. From time to time, Joe also talks to the camera, but his musings on reality ('All I wanted to do was see, to encounter myself in the midst of my being ...') are as open-ended as the sight of an image receding into the infinity provided by two mirrors.

"Instead, Coming Apart compels attention as an anthology of various types of sexual endeavor, all photographed from the fixed position that in stag films is a matter of economic necessity (each new camera set-up adds more money to the budget) but here is a matter of conscious style." In fact, Canby suggested, "Coming Apart is an unequivocably entertaining movie only if you cherish the rigorous ceremonies enacted by participants in stag movies, photographed with the kind of frontal, skin-blemished candor that shrivels all desire. As an attempt to elevate pornography (or what we thought was pornography until all the points of reference came unstuck) into art, it is often witty and funny but it fails for several reasons, including Ginsberg's self-imposed limitations on form (to which he's not completely faithful)."

Locally, when Coming Apart had a one-week revival run at the Lumiere 10 years ago, Edward Guthmann from the San Francisco Chronicle complained: "The claustrophobic intimacy of Coming Apart is supposed to bring us inside Joe's head to share his agony and self-loathing, one supposes. Instead, the whole set-up of the hidden camera and the mirror—and the implied correlation between psychiatry and voyeurism—feels like a gimmick, an arty pose." (Time likewise criticized that Ginsberg's manifest intent to make his film "a set of X rays" comes off instead as "only a suite of poses.") Guthmann, further contextualizing that 1969 was the year of such films as Easy Rider, Medium Cool and Midnight Cowboy, suggested that—though cultural forms and sexual behavior were being turned inside out and Coming Apart probably had some relevance for some people—"today it looks phony and self-important. It's meant to be unvarnished and truthful but the situation it portrays—of Torn lying back while a series of desperate women throw themselves at him—is pure fantasy, the silly wish fulfillment of a Playboy subscriber."

Locally, when Coming Apart had a one-week revival run at the Lumiere 10 years ago, Edward Guthmann from the San Francisco Chronicle complained: "The claustrophobic intimacy of Coming Apart is supposed to bring us inside Joe's head to share his agony and self-loathing, one supposes. Instead, the whole set-up of the hidden camera and the mirror—and the implied correlation between psychiatry and voyeurism—feels like a gimmick, an arty pose." (Time likewise criticized that Ginsberg's manifest intent to make his film "a set of X rays" comes off instead as "only a suite of poses.") Guthmann, further contextualizing that 1969 was the year of such films as Easy Rider, Medium Cool and Midnight Cowboy, suggested that—though cultural forms and sexual behavior were being turned inside out and Coming Apart probably had some relevance for some people—"today it looks phony and self-important. It's meant to be unvarnished and truthful but the situation it portrays—of Torn lying back while a series of desperate women throw themselves at him—is pure fantasy, the silly wish fulfillment of a Playboy subscriber."Meanwhile at The Examiner, Wesley Morris added: "Bizarre, irritating, self-indulgent to the point of narcissism, Coming Apart is a stark, necessary reminder of what kind of actor Torn was when the nature of the work he was doing allowed him to fold a psyche into his particular brand of menace."

More recent critics have found much to recommend the film, though acknowledging it remains very much a product of its time. IndieWIRE crowns it "One of the most challenging, visionary, important films of independent cinema." At A.V. Club Nathan Rabin observes: "Coming Apart's secret-camera gimmick proves tremendously limiting, but it's also an audacious stylistic choice that lends the film a harrowing, claustrophobic intensity that can be almost unbearable." He concludes the film is "disconcertingly original, if self-indulgent and formless. A noble, if not entirely successful, experiment that promises more than it can deliver, it's a fascinating, frustrating time capsule that too often lapses into tedium."

More recent critics have found much to recommend the film, though acknowledging it remains very much a product of its time. IndieWIRE crowns it "One of the most challenging, visionary, important films of independent cinema." At A.V. Club Nathan Rabin observes: "Coming Apart's secret-camera gimmick proves tremendously limiting, but it's also an audacious stylistic choice that lends the film a harrowing, claustrophobic intensity that can be almost unbearable." He concludes the film is "disconcertingly original, if self-indulgent and formless. A noble, if not entirely successful, experiment that promises more than it can deliver, it's a fascinating, frustrating time capsule that too often lapses into tedium."PFA's "Eccentric Cinema: Overlooked Oddities and Ecstasies, 1963–82" continues this evening with a new print of L.Q. Jones' A Boy and His Dog (1975).

Cross-published on Twitch.