As part of the recent PFA series "A Thousand Decisions in the Dark", David Thomson offered commentary on Billy Wilder's Some Like It Hot (1959). Though delayed by pneumonia from participating in a timely way, I nonetheless wanted to contribute Thomson's appreciation of this all-time Wilder classic to the Billy Wilder Blogathon, hosted by Jeff Duncanson at Filmscreed.

* * *

Black comedy. One of the quickest ways to lose your reputation for being a jokester and to have the room go silent around you is when you tell a black joke that you think everyone will get and you realize you've gone too far. In a world where it's almost impossible to tell a joke without it being black, maybe that's some reason for the decline in comedy.

[Some Like It Hot] is known now—and I hope it will repeat its reputation tonight—as being a film that has people bursting out with laughter and then being told by their companions to shut up so [they] can hear the next line. Because in film—as you can't do in theater—you can't let the laughter pause last as long as it will do naturally. You can see, I think, when you make a comedy, leaving the pause at the right length is a tremendous sign of judgment and taste. Nothing kills any film more than pauses.

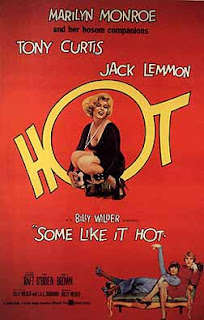

Billy Wilder really did not know for sure—and I hope to try to make it clear to you—just what a daring venture this film was. It was previewed, as most films were and still are, to try to get a feeling of what audiences were going to do with it, which would help the publicity people in theory. That's how [the publicists] would argue, "We'll show it to people so we can know how they're responding so we can respond to their responses", a sort of absurd double-think. There was a preview in the Pacific Palisades, full house, 700 people or so, and Wilder's at the back with I.A.L. Diamond, his writing partner, and everybody else from the Mirisch Brothers and several people from United Artists who were crossing their fingers. Because the film cost $2.8 million, which for those days was a lot, and it went way over budget and I dare say some dark spirits in the audience might be able to guess why it went over budget so much. Anyway, there are 700 people and everybody's waiting. It's the first time they've shown it to a live human audience. Imagine! Why do people do these things? They must be pushed by some desperate force. To expose yourself to an audience. The film starts and it does start like a gangster film, talking about the mixture of genres going on in this period, this does not look like what it's going to turn into, which may be a warning to ask yourself, has it really turned into what you think it's turned into? It looks like a gangster film and it's not well-signalled. So it didn't get the laughs at first. The film was deliberately constructed so that the first few minutes the audience would be saying, "What is this? Why's it called Some Like It Hot? It sounds playful when it's not looking playful at all." But then there a few laugh moments, when you discover what's in the hearse. If that's not going to get a laugh, then you may be in trouble. Anyway, this night at Pacific Palisades, one person in the front of the theater laughs out loud when they show you what's in the hearse. Wilder shakes his head and he thinks doom. Wilder was extremely competitive. He wanted every film to be a big hit. It went on this way all through the [preview]. Nobody laughed. It was an audience of kids. They'd been there to see something else. [But] there's this one guy down in the front who was the perfect audience and Wilder wanted to see who the guy is. He walks down to the front of the theater and it's Steve Allen. He always said to Steve Allen, "There aren't enough of you, Mr. Allen."

David Selznick, who knew [Wilder] socially, liked him. Wilder was a very witty, pungent, funny guy, a great entertainer. You always wanted to go to one of his parties at his house to see his painting collection. He rated his films by the paintings he acquired. David Selznick said to him at one of these occasions, "Well, Billy, what are you going to do next?" Wilder had this reputation for departing [from the commonplace]. He was one of those directors in the late '50s who was doing exactly what we've been talking about in this series of coming up with unexpected things. He said, "Well, I think what we'll do is we'll have a gangster film and we'll have a lot of murder, a lot of slaughter, and [it'll be] very funny." Selznick, who was not long in humor, looked at him and said, "Billy, you can't do that." Wilder cocked an eyebrow and took it as a provocation. He said, "I can't do it, Mr. Selznick? I can't do it? They told you you couldn't do Gone With the Wind." Selznick said, "You have to understand. I think I have a certain duty here. It's not American. You can frighten the life out of Americans and you can give them a very good, funny time; but, be careful about confusing the two."

Look at our world today, you know how the times have changed and how wrong Selznick was. Could you live in times that are more terrifying and more hilarious at the same time? Ten years before, Wilder had come out of a screening at the Selznick lot of a film called Sunset Boulevard. Selznick's father-in-law had gone up to [Wilder] and the legend says that he spat in Wilder's face and said, "How dare you make a film that bites the hand that has been feeding you?" Sunset Boulevard—one of the first films to say, "This could be a madhouse, this place called Hollywood." Not the wonderful place of A Star Is Born. Not the place where everybody believes in what they're doing but a place where tortured people are living nightmares of lost dreams, where people have compromised too many times. Wilder said, "We'll see what the public thinks." The public took it. Wilder, even though he was [an expatriated] German, had an extraordinary instinct—a much better instinct it proved than either Mayer or Selznick—for what the American public would like. Which is why he was so devastated at the end of his life when he lost the instinct. It's a funny thing: you can have an instinct about public taste, you can say, "Are they ready for this?" and they are. You can do it twice in a row and you think, "I've got it. I've really got this show business thing." Then you make a third film, a film of which you're the most confident of all, and the public doesn't come to see it. No one can explain it. To this day, the wisdom about films is constantly being proved wrong on a Friday afternoon. That's all it takes. Friday afternoon tells you.

I saw a press screening several months before it opened of Titanic in Hollywood. Talk about dark humor, gallows humor, going around that screening room. Everybody was saying to everyone they knew in the press, "Remember me. I'm going to need a job in two weeks time." Because this film, which was actually sponsored by two studios, cost so much money. "This film is going to kill two studios." [Yet,] it made more money than any film ever made before. You just can't tell.

Wilder remembered a silly German film [Fanfaren der Liebe, 1951] in which two guys who want to work as musicians can't get a job in a male band, dress up as women, and join a girl's band. The film had done no business at all but it had stuck in his head somehow. I wish he were here because I would love to push him on why he remembered it. He had personally bought the rights to it for a remake. Technically, [Some Like It Hot] is a remake of that German film. But he said straightaway, two guys are not going to dress up as women unless they're under some extraordinary pressure. The fact that they want to play music, I don't believe it. So he said, we've got to have the pressure; the pressure is going to do this.

[Wilder] worked always with a writing partner. If you look at his films, going back, the first man was a man named Charles Brackett. [Wilder] dropped Brackett—Brackett never knew why—and he picked up I.A.L. Diamond as the partner at the time of Some Like It Hot. Whenever they were asked who did what, Diamond would say, "Well, I type and [Wilder] walks around the room." There are brilliant writers in film—and film and theater are the only mediums in which is true, maybe television—where some people can only do it if they're doing it with someone else. To write a novel, to write a poem, people feel they have to be alone. There was a togetherness in writing for film that I think has to do with a very simple thing. I give you a line and I look at your face and you look at me and you say, "That was a line?" I know I've got to go back. If you laugh, and y'know, there are people who will laugh at the right time make wonderful writing partners. Wilder was clearly the driving force in the partnership but he could not do it without someone else.

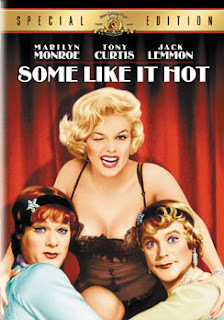

Wilder came in one day and he said, "I've got it!" He says, "These are two musicians but they are on the run." Diamond says, "On the run from what? They've escaped from prison, you mean?" [Wilder] says, "No, no. I don't think they've escaped from prison. They're not that bad. But they're not far from it. Maybe they have seen a gangland killing." Immediately, you have to make this film in Chicago in the 1920s, which had not really been a factor—they didn't quite know where they were going to set it until then—and the mob is after them because what they have seen is a version of the St. Valentines Day massacre. [Some Like It Hot] became one of those comedies that has the St. Valentines Day massacre in it. It clicked. They started saying, "Two guys. Who are the guys?" Wilder said, "I see Frank Sinatra. I see Frank Sinatra in this." Diamond says, "You can get Frank Sinatra in a dress?" Wilder says, "Well, we'll invite him to dinner. We will talk to him about putting on a dress." Somehow, word must have gotten back. Sinatra doesn't even come to the dinner. Wilder says, "I know the other guy though. He is the prettiest actor in town. He's going to be some doll. Tony Curtis." They offered it to him. Jack Lemmon—who is probably the person people most associate with the film and it's the most outrageous performance and the most sexually provocative performance some would say—Lemmon came in later and, of course, Marilyn.

Wilder had worked with Marilyn before on a film called The Seven-Year Itch and they had a terrible time. This was earlier on, about five years before, and they had a very bad time. People came up to Wilder and said, "You remember the terrible time you had with Marilyn back then?" She couldn't learn her lines. She'd show up late and this kind of thing. Wilder said, "I have to believe she's a reformed character. She's married to that Arthur Miller now. She must be more serious. She was married to a ball player back then." So they hired Marilyn; the most expensive part of the budget, although this is a Hollywood that distrusts her and is very uncertain about how to use her, to put it mildly. [Marilyn Monroe is] one of the great stars who has never been properly used, though that's as much her fault as other people's. They call a celebration dinner to sign the contracts at the house of Lew Wasserman, who is very important in the background of the deal, he's the agent to many of the people who are on the film. The dinner is for 7:00 and Marilyn gets there at 11:20. There's a lot of nodding of heads. It turns out to be a nightmare, aggravated by the fact that she's almost certainly—you can never quite tell with Marilyn—but [she] almost certainly got pregnant towards the end and lost the child. But there was a line—"It's me, Sugar"—if Marilyn could have done that, it would have been in the film. For three days they were trying to get her to say, "It's me, Sugar." She got the line wrong. She got the emphasis wrong.

There were these guys in drag and I won't go into detail but they had to wear steel jockstraps through the shooting of the film and they said it was extremely uncomfortable. Lemmon noticed that Curtis never went to the bathroom all day long and went up to him near the end of the film and said, "How do you do it?" Curtis said, "I've got my own method and I'm not telling." For these guys every day they were on the set they would get teased by everybody. They were getting paid to get teased so it was all right, but, they were both extremely proficient handlers of lines and comedy. Only a few years before Curtis had spoken the lines of Sweet Smell of Success and to see that this bimbo couldn't say, "It's me, Sugar"—she'd say, "Sugar, I" and things like that—they put it up all over the set. You have to say to yourself, "Was she that foolish or was she that controlling?" Many people did. Many people thought she did it to draw the film to herself. Of course, it led to something that actors hate. It's a terrible problem when you're making a film. There are certain actors—Clint Eastwood is famously one—if he can't do a scene on the first or the second take, you might as well drop the scene because he isn't going to persevere. Sinatra was exactly like that. If you couldn't get it straightaway, if it wasn't natural, it's wrong. And he may have been right. Actors have great instincts. There are other actors, method actors who like to work up to it. If you've got an actor who's very good on take two playing a lot of scenes in the film with an actor who likes 10-12 takes, you've already got a problem. Marilyn needed 60-70 takes just to get it in the can competent. That's what leads to one of the great black lines of all time, when somebody said to Tony Curtis, who in his male attire portion of the film where he is doing Cary Grant, has this extraordinary scene—I think it should have been censored, it's so indecent; but, the censors I think didn't get it—this extraordinary scene where he's having to encourage [Marilyn], to teach her how to really kiss and get him excited because he's never been excited—someone came up to him after days of this sequence and said, "Not a bad way of earning a living." [Curtis] said, "You won't believe it. It's like kissing Hitler." That's a pretty black line. There was a lot of extraordinary animosity on the set in this film and Wilder was having to control it. One of the great things about [Some Like It Hot] is that I don't think that you would come away from the film and think anything other than that they were having a ball. It looks and feels as if they're best friends and it's just a terrific experience.

Wilder always shot what he and the other guy had written. He did not like second guessing a script. Hardly a line would be changed. One of the questions I would come back with later is: does [Some Like It Hot] reliably become a comedy or does it always stay a macabre film? One of the things about Wilder's films that is so interesting is—and I'm thinking of films like Double Indemnity, Ace in the Hole, and The Lost Weekend as well as [Some Like It Hot]—I don't think Wilder liked the [characters] terribly. Often he's very tough on them and he puts them in embarrassing situations and he makes fun of them. There's a lot of laughter at Marilyn's expense in [Some Like It Hot]. I'm not saying she hadn't earned it as she may have done but I do think that the way she was treated in this film only added to her heartbreak—which I don't think you can question—about her being so misunderstood. She believed that she was the person that the film's constantly telling dirty jokes about. It's strong in this movie.

Another question I would ask about the film is the last line—one of the great last lines—is it just a get-off? A way to end the film, in other words? I think they have real problems about ending this film because if you look at the film, you will find that it's doing something that's very unusual in a film, it pretty well accelerates. It goes faster and faster. Now there's terrible danger with a film that's going like that because it will get out of control and it will crash at the end. So how you end a film like that is very interesting. They had lots of wild ideas. George Raft was going to come back from the dead and do a tango with Marilyn Monroe and then they thought, "Could we ever get her to learn the tango?" One day Diamond said outloud the last line. Wilder said, "Hmmmmm. Well, it will do for now. We'll write it in and if we think of something better, we'll move that in." [That last line is] probably the thing about which the film is best known and it's an extremely ambiguous line.

People teased Wilder when the film came out in 1959-60. This was a time when nobody was known outside of Hollywood as being gay. The place was stacked with them but nobody knew it. Somebody said to Wilder, "So Wilder, people are going to start telling stories about you." In his characteristic way, he would have said something like, "Oh, I'll just go and seduce another three or four women." That mind set, that thought that if you don't want to be thought gay you just fuck more women, no, we're much more sophisticated and we know that sometimes that behavior can be very much closeted of that attitude. Wilder's films are full of male bonding. Think of Edward G. Robinson and Fred MacMurray—"I love you too, Keyes"—remember? In Double Indemnity? Think of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, probably the film that Wilder most wanted to make. It was a crashing disaster in 1970. The film that really suggests flat out—and by 1970 a lot had changed so it was easier to do this—but Holmes and Watson work better for that time if they are a gay couple. I just don't know. Wilder was married to two beautiful women. Again, we know that doesn't prove anything. Wilder had also been raised in a society in Vienna where there was a great deal of [closeted homosexuality]. I think as you look at his work there's a fascination that is partly attraction, partly horror, but I think it's there and I think it's time people started talking about this. I don't think this ending is just a get-off, although it is a great get-off.

Wilder, by the late 1980s, sat in an office every day in Beverly Hills—I saw him there once—with his six Oscars lined up behind him, writing scripts Hollywood turned down every time. I don't know if the scripts were good. Some publisher ought to publish a few of them so that we could see. Maybe he had lost his touch. That's what they said to him. He was as bitter as can be because before his 50s, 60s, there was no one who had made as much money as a director in Hollywood as he had done. He said, "A guy doesn't lose his touch. I go to an art gallery and I know which is a good picture still. I go to a café or a restaurant and I still know who the beautiful, sexy girls are. I can still tell them. I know. I can still make a film." But the system wouldn't let him because they believed that he was of an age where you really couldn't expect to have it together anymore. It was an extraordinarily cruel thing. It's a marvel that someone like Lew Wasserman who had been a big part of his life couldn't just say, "Let the guy make a film. Let's see. If we lose $2,000,000, all right, we lose $2,000,000. We make so much crap all the time that we lose $2,000,000 on so what if he loses $2,000,000? We owe it to him. Maybe it won't lose $2,000,000. Maybe it will be another Some Like It Hot?" Because maybe the guy was just as alert as anybody. He took me around his art collection and he watched me. He didn't look at the paintings. He knew the paintings. He watched me responding to the paintings. He said, "Oh, you like that one, eh? You've got a dirty mind." He watched people like a young man. A good sign, I think, that he could have gone on making films but was not allowed to.

Anyway, here we are, 46 years later and I hope that those of you who have never seen Some Like It Hot are going to be amazed and laugh your heads off. I hope you still catch all the lines. There are some filthy lines in the film. Clearly the censors didn't know how to get past them. Finally, this is a film in which people making the film have said, okay, we've put George Raft in the film. He plays the gangster. That's good. George Raft always played gangsters. What did George Raft do? He tossed coins in his films. Okay. We'll play a little coin tossing joke on George Raft. The film is full of in jokes. Now once upon a time you couldn't make in jokes in the movies because everybody said that millions of people out there won't get in jokes. Wilder was dealing and working at a time in film history where he said, "Everybody knows what George Raft is famous for." Nobody knows anything about George Raft except he tosses a coin. The poor dear. That's all he could ever do. Sometimes he couldn't catch the coin. See if you can see the names of any famous agents in the film. Keep your eyes peeled for things like that. And film references because it's full of them. Wilder was confident in 1960 that the audience would pick up on them for it to work.