[Our thanks to intern Kurtiss Hare for offering these capsule reviews to The Evening Class.]

[Our thanks to intern Kurtiss Hare for offering these capsule reviews to The Evening Class.]Tokyo Story / Tokyo monogatari (Ozu Yasujirō, 1953)—After almost 70 years of smiling, the faces of Mr. and Mrs. Hirayama are adorned with the signature shadows of time's crescent shaped engraving. A train ride to Tokyo is in order, where they plan to meet up with several of their children, some of whom have families of their own. Tokyo is practically a world away from their home in Onomichi, a sleepy riverside town in the Hiroshima prefecture of Japan. Upon arriving, the two are met by their relatives, whose reactions betray attitudes of muffled inconvenience and snippy annoyance. In the final days of the trip, another of time's well-worn maneuvers makes an appearance, subtly conjuring tears at the eyes of those who witness.

Set behind the opening credits for Ozu Yasujirō's Tokyo Story, stretching from corner to corner in an extreme close-up, is a length of burlap textile. Its fibers are arranged in a grid, whose regularity and square proportions reverberate in the many taut and geometrically composed images of the Japanese domicile. When Ozu's camera is inside, it's crowded by its own perspective. Dining rooms resemble puzzle boxes with lines that carve away emptiness, such that sitting seiza seems not only polite, but necessary. Entrance ways on side walls skew so thin that actors who use them seem to blink in and out of recognizable space. When his camera is outside, we are shown great temples, fields, smoke stacks, trains on railways, and tugboats on channels. In general, we are relieved to be there. Tokyo Story dabbles in death without succumbing to morbidity and it touches tragedy without defaulting to cynicism. Its outlook on familial relationships is a rich one; it's no pauper's fabric. [Cinefrisco.]

Set behind the opening credits for Ozu Yasujirō's Tokyo Story, stretching from corner to corner in an extreme close-up, is a length of burlap textile. Its fibers are arranged in a grid, whose regularity and square proportions reverberate in the many taut and geometrically composed images of the Japanese domicile. When Ozu's camera is inside, it's crowded by its own perspective. Dining rooms resemble puzzle boxes with lines that carve away emptiness, such that sitting seiza seems not only polite, but necessary. Entrance ways on side walls skew so thin that actors who use them seem to blink in and out of recognizable space. When his camera is outside, we are shown great temples, fields, smoke stacks, trains on railways, and tugboats on channels. In general, we are relieved to be there. Tokyo Story dabbles in death without succumbing to morbidity and it touches tragedy without defaulting to cynicism. Its outlook on familial relationships is a rich one; it's no pauper's fabric. [Cinefrisco.] Dragnet Girl / Hijosen no onna (Ozu Yasujirō, 1933)—A bold ruby dresses enchanting Tokiko's finger. The jewel was not given to her by her "steady," Joji, a former champion pugilist turned gangster, whose furious extracurricular fisticuffs also go undisputed. Instead, as Tokiko teasingly recounts, it was the gift of a co-worker, eager to buy her favor. Her incendiary remarks were not without provocation: Joji's been uncharacteristically domesticated by a flirtatious encounter with the angelic Kazuko, and Tokiko is having none of it. Kazuko has turned on the charm in order to redeem her brother, Hiroshi, a young boxer who's taken to apprenticing Joji's illicit exploits. Tokiko, struggling to rectify her partnership in crime, suggests a final heist that culminates in a flurry of action.

Dragnet Girl / Hijosen no onna (Ozu Yasujirō, 1933)—A bold ruby dresses enchanting Tokiko's finger. The jewel was not given to her by her "steady," Joji, a former champion pugilist turned gangster, whose furious extracurricular fisticuffs also go undisputed. Instead, as Tokiko teasingly recounts, it was the gift of a co-worker, eager to buy her favor. Her incendiary remarks were not without provocation: Joji's been uncharacteristically domesticated by a flirtatious encounter with the angelic Kazuko, and Tokiko is having none of it. Kazuko has turned on the charm in order to redeem her brother, Hiroshi, a young boxer who's taken to apprenticing Joji's illicit exploits. Tokiko, struggling to rectify her partnership in crime, suggests a final heist that culminates in a flurry of action. Dragnet Girl is an incredibly kinetic piece of silent cinema. Ozu's left jab is an attraction of chaotic imagery—gymnastic rings in multiphase, pendular action; snooker balls rebounding against their bumpers; jump-ropes in full swing; and a gangster whose aggressive tic is to toss alarm-clocks where others might substitute a coin. His right hook is a precarious braid of aggressively interwoven trajectories. His final blow is a fascinating and exhaustive depiction of the facets of physical violence: knockouts, wake-up calls, and playful jabs. This is a jarring and spectacular combination, to be sure, but it's perhaps a bit below the belt. Dragnet Girl's universe is one where all possibilities are contenders, where the function of a dice roll is to span instead of to permute. His character's motivations are similarly far-fetched. Fortunately, Ozu fills these gaps with comic exaggerations that generate goodwill where others might substitute exasperation. [Cinefrisco.]

Dragnet Girl is an incredibly kinetic piece of silent cinema. Ozu's left jab is an attraction of chaotic imagery—gymnastic rings in multiphase, pendular action; snooker balls rebounding against their bumpers; jump-ropes in full swing; and a gangster whose aggressive tic is to toss alarm-clocks where others might substitute a coin. His right hook is a precarious braid of aggressively interwoven trajectories. His final blow is a fascinating and exhaustive depiction of the facets of physical violence: knockouts, wake-up calls, and playful jabs. This is a jarring and spectacular combination, to be sure, but it's perhaps a bit below the belt. Dragnet Girl's universe is one where all possibilities are contenders, where the function of a dice roll is to span instead of to permute. His character's motivations are similarly far-fetched. Fortunately, Ozu fills these gaps with comic exaggerations that generate goodwill where others might substitute exasperation. [Cinefrisco.] Sisters of the Gion / Gion no shimai (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1936)—For the enterprising geisha, the ability to afford a fetching kimono can make the difference between landing that next client and having to go "splitsies" on tomorrow's bowl of breakfast ramen. That's why, when her older sister's patron has gone bankrupt, Omocha, an indignant storm cloud of selfsame skill set and more ambitious career goals, takes matters into her own hands. Spurned and milked (of their money), a string of her customers catch on to the game. When they collude to take revenge, her mettle is put to its fiercest test yet.

Sisters of the Gion / Gion no shimai (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1936)—For the enterprising geisha, the ability to afford a fetching kimono can make the difference between landing that next client and having to go "splitsies" on tomorrow's bowl of breakfast ramen. That's why, when her older sister's patron has gone bankrupt, Omocha, an indignant storm cloud of selfsame skill set and more ambitious career goals, takes matters into her own hands. Spurned and milked (of their money), a string of her customers catch on to the game. When they collude to take revenge, her mettle is put to its fiercest test yet. Kenji Mizoguchi's Sisters of the Gion depicts a probably too-familiar kind of modern depravity; it's cornered between increasingly outmoded Japanese structures—lopsided gender roles, obsolete professions, and ancestral veneration—and adaptation born of an instinct for survival: in want of food, shelter, and a sense of security. In a particularly revealing shot, we're shown Omacha loudly complaining to her sister about the disloyal, domineering, and inconstant nature of men, which is visually hole-punched by her hasty and irreverently executed bows to a series of Shinto shrines. The streets of Gion are cavernous and empty; here, Mizoguchi rings out the unanswered, echoing call of a lone vendeuse. This inhospitable world provides a suitably dim backdrop against which Omacha's tenacious and vibrant schemes pop delightfully. [Cinefrisco.]

Kenji Mizoguchi's Sisters of the Gion depicts a probably too-familiar kind of modern depravity; it's cornered between increasingly outmoded Japanese structures—lopsided gender roles, obsolete professions, and ancestral veneration—and adaptation born of an instinct for survival: in want of food, shelter, and a sense of security. In a particularly revealing shot, we're shown Omacha loudly complaining to her sister about the disloyal, domineering, and inconstant nature of men, which is visually hole-punched by her hasty and irreverently executed bows to a series of Shinto shrines. The streets of Gion are cavernous and empty; here, Mizoguchi rings out the unanswered, echoing call of a lone vendeuse. This inhospitable world provides a suitably dim backdrop against which Omacha's tenacious and vibrant schemes pop delightfully. [Cinefrisco.] Street of Shame / Akasen chitai (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1956)—Stationed atop a cluttered desk, a battery-powered radio blares commentary on an important piece of legislation. If passed, the Baishun Bōshi Hō would directly impact the lives of Yasumi, Mickey, Yumeko, Hanae, and Yorie. These five prostitutes, in the employ of the Dreamland Brothel in the Tokyo outskirts, and many others like them, would be made into criminals. Bound together by a common alienation, the role these women play for each other is both supportive and enabling. The ensemble action comes to a head when—for a set of reasons as diverse as their personalities—the ladies experiment with the notion of parting ways with their patrons.

Street of Shame / Akasen chitai (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1956)—Stationed atop a cluttered desk, a battery-powered radio blares commentary on an important piece of legislation. If passed, the Baishun Bōshi Hō would directly impact the lives of Yasumi, Mickey, Yumeko, Hanae, and Yorie. These five prostitutes, in the employ of the Dreamland Brothel in the Tokyo outskirts, and many others like them, would be made into criminals. Bound together by a common alienation, the role these women play for each other is both supportive and enabling. The ensemble action comes to a head when—for a set of reasons as diverse as their personalities—the ladies experiment with the notion of parting ways with their patrons. Shame isn't the only adjective to prowl Mizoguchi's intimidating streets. There are howling cat-calls and frenetic physical confrontations; it's an open air market of push comes to shove. A positively freaky theremin warbles behind the action, beaming us into a kind of misconfigured, alien world. Extravagant and erotic statues line our near vision, obstructing us from entering the brothel's rooms with libido unengaged. Mizoguchi holds us complicit in the agony and glory of these women through a thorough and unsettling demonstration: the complete breakdown of a prostitute. [Cinefrisco.]

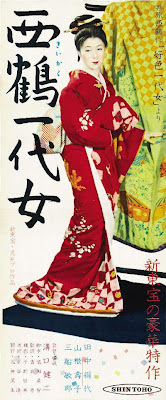

Shame isn't the only adjective to prowl Mizoguchi's intimidating streets. There are howling cat-calls and frenetic physical confrontations; it's an open air market of push comes to shove. A positively freaky theremin warbles behind the action, beaming us into a kind of misconfigured, alien world. Extravagant and erotic statues line our near vision, obstructing us from entering the brothel's rooms with libido unengaged. Mizoguchi holds us complicit in the agony and glory of these women through a thorough and unsettling demonstration: the complete breakdown of a prostitute. [Cinefrisco.] The Life of Oharu / Saikaku ichidai onna (Kenji Mizoguchi 1952)—Oharu's tough gal schtick isn't enough to fend off Katsunosuke's amorous advances. True, if their fling were publicized, Japan's Edo period punishment for breeding between the lines would be enacted swiftly and finally. And so was the fate of the briefly successful, lowly page Katsunosuke, who—despite the perks of Oharu's hoi polloi heritage—wanted only to marry for love. This retributive rejoinder is the first in a long procession of responses—with layovers at palaces and whorehouses, convents and domeciles—to quandaries that Oharu's actions really haven't posed.

The Life of Oharu / Saikaku ichidai onna (Kenji Mizoguchi 1952)—Oharu's tough gal schtick isn't enough to fend off Katsunosuke's amorous advances. True, if their fling were publicized, Japan's Edo period punishment for breeding between the lines would be enacted swiftly and finally. And so was the fate of the briefly successful, lowly page Katsunosuke, who—despite the perks of Oharu's hoi polloi heritage—wanted only to marry for love. This retributive rejoinder is the first in a long procession of responses—with layovers at palaces and whorehouses, convents and domeciles—to quandaries that Oharu's actions really haven't posed. The Life of Oharu is perhaps too optimistic a titling for the inauspicious chain of events that befall our director's trampled heroine. Analogous to the Bunraku puppet's operator, Mizoguchi employs a fine motor control: fluid and deliberate camera movements, peeking around a corner or straining down to peer through an opening, in order to reveal some scene-darkening aspect of the action space. He precisely denies us the few joys that Oharu must have experienced by fading instead to black, tenuto: the woman gives birth to a child and she finally does marry (for love). What's left is cruelty and shadow: a woman whose every round-faced, translucent-lobed, diaphonous-nailed conformance to ideal beauty is a commodity for trade and consumption. And consumed she is, to the point of exuding a goblin-like aura that serves for her latter day customers as an object lesson in chastity. What we know about Oharu is what has happened to her, and where we're locked out of a fuller, more recognizable humanness, we're indeed thankful for the lush cinematic treatment of what's there. [Cinefrisco.]

The Life of Oharu is perhaps too optimistic a titling for the inauspicious chain of events that befall our director's trampled heroine. Analogous to the Bunraku puppet's operator, Mizoguchi employs a fine motor control: fluid and deliberate camera movements, peeking around a corner or straining down to peer through an opening, in order to reveal some scene-darkening aspect of the action space. He precisely denies us the few joys that Oharu must have experienced by fading instead to black, tenuto: the woman gives birth to a child and she finally does marry (for love). What's left is cruelty and shadow: a woman whose every round-faced, translucent-lobed, diaphonous-nailed conformance to ideal beauty is a commodity for trade and consumption. And consumed she is, to the point of exuding a goblin-like aura that serves for her latter day customers as an object lesson in chastity. What we know about Oharu is what has happened to her, and where we're locked out of a fuller, more recognizable humanness, we're indeed thankful for the lush cinematic treatment of what's there. [Cinefrisco.] Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)—A priest has his proverbs. A woodsman, his bravery. But for the two devastated men crouching under the looming wooden arches of a massive dilapidated structure known as the Rashōmon gate, no character armor could provide sufficient protection from the barrage of twisted scenes to which their eyes bore witness. When an inquisitive wanderer joins their company, they recount for him a braided tale of bloodshed, in which each perspective offers competing motivations and culpability for the violence. It is said that, at the Rashōmon gate, a vicious demon was bested by a valiant samurai. But to comprehend the intricacies of the plots our witness offers us is to know something of the dark corners where this demon lurches still.

Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)—A priest has his proverbs. A woodsman, his bravery. But for the two devastated men crouching under the looming wooden arches of a massive dilapidated structure known as the Rashōmon gate, no character armor could provide sufficient protection from the barrage of twisted scenes to which their eyes bore witness. When an inquisitive wanderer joins their company, they recount for him a braided tale of bloodshed, in which each perspective offers competing motivations and culpability for the violence. It is said that, at the Rashōmon gate, a vicious demon was bested by a valiant samurai. But to comprehend the intricacies of the plots our witness offers us is to know something of the dark corners where this demon lurches still. Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon—while decidedly sporting frayed narrative edges—is an elegantly packaged little piece of cinema. There must be a statistical limit to the number of images a film can impress upon the cognitive firmament, and Rashomon certainly tests that limit: the impermeable waves of rain that flood the gate's shingles, the glint of the sun battling its way through the forest's protective canopy, the gnarled shadowy hands of a freshly dispatched victim. Kurosawa's camera is locomotive, hatcheting its way through dense patches of bamboo and brush. His staging can also be supremely and hilariously absurd: one scene featuring the sotto voce swordplay of two tremendous cowards is both high slapstick and poignant faceting. Many films require an active participation of the audience, but where Rashomon stands above its peers is in its ability to approach this relationship with thoughtful ingenuity. [Cinefrisco.]

Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon—while decidedly sporting frayed narrative edges—is an elegantly packaged little piece of cinema. There must be a statistical limit to the number of images a film can impress upon the cognitive firmament, and Rashomon certainly tests that limit: the impermeable waves of rain that flood the gate's shingles, the glint of the sun battling its way through the forest's protective canopy, the gnarled shadowy hands of a freshly dispatched victim. Kurosawa's camera is locomotive, hatcheting its way through dense patches of bamboo and brush. His staging can also be supremely and hilariously absurd: one scene featuring the sotto voce swordplay of two tremendous cowards is both high slapstick and poignant faceting. Many films require an active participation of the audience, but where Rashomon stands above its peers is in its ability to approach this relationship with thoughtful ingenuity. [Cinefrisco.]Cross-published on Twitch.