|

| Photo: Austin Young |

Ian Harvie began his stand-up comedy career in his home state Maine in 2002, then migrated to Los Angeles in 2006 when he began touring with Margaret Cho as her opening act. He began his solo headlining career in 2009, and has had his act memorialized in the documentary Ian Harvie Superhero (2013). More recent credits include episodic turns in the Golden Globe®-winning television series Transparent (2014). He's currently shooting the short film Upended (2016).

* * *

Michael Guillén: It's a great honor to talk to you today, Ian. Congratulations on being a rising star on the comedy circuit. You're probably the first transgender stand-up comic hit that I've heard of.

Ian Harvie: Well, thank you! Thank you very much.

Guillén: That must feel good?

Harvie: There are so many transgender comics out there doing stand-up.

Guillén: Is that true?

Harvie: There are now. I was the only transgender person I knew doing stand-up when I started. There were definitely performers, artists, actors, lots of theater people, but I was the only stand-up I knew that was traveling around 13 years ago trying to tell people who I was through humor. It's amazing to see a lot of people out there now, but to have people lift me up and let me be seen and heard and to have someone like you say that what I'm doing means something to you is really beautiful to me. So thank you. Thank you so much.

|

| Photo: Austin Young |

Harvie: One of the things I don't do is self-hate. I'm not a self-loathing comic. I endear myself to the crowd before I lay who I am on them. By the time I lay who I am on them, if they're incensed by it for some dumb reason, then they're clearly assholes because they've already liked me. My plan is always to make you like me before we ever get to the stuff about my identity and sexual politics, being trans and that experience.

But here's the other thing: the rule in comedy is that if it's your story, if you're telling your story—and that's the rule of any storytelling at all—your story is inarguable. I just get up and tell my story and nobody can come up to me afterwards and say, "No, suh. That's not true." Yes, it is. It happened to me and that's how I speak of it. That's how I share my story. Also at the end, without their really knowing it, they've probably learned something. They laugh, but they're also thinking, "I didn't know that."

Guillén: Absolutely. As an elder gay male who's experienced queer activism from the '70s on, the transgender voice is, perhaps, the most complicated story to tell and the most difficult to communicate and incorporate.

Harvie: Let me make it real easy. You know what? Everybody around us right now, everybody on this campus, everybody outside this campus throughout Boise, all the way to San Francisco, especially the gay men in San Francisco, feel uncomfortable about their bodies in direct relation to their masculinity or their femininity, their gender specifically. No one feels 100% okay about their bodies. If they do, then they're the weirdo.

When I first came out I thought, "Oh, I'm the only one that's ever felt this way." That's silly. I met other guys like me and started to feel more comfortable, but then I started to look around at people who—even if they're comfortable with the gender they were born with, their gender assignment—I began to realize that they are also modifying their bodies. Women are getting breast implantations to feel more feminine in their bodies. I took mine off to feel more masculine. It's the same motivation. We're all the same. We're all doing the same things and all feeling the same way but what we choose to do with it is different person to person. So, for me, everybody's trans. You are. They are. We don't stop to take a beat and a breath to think, "I wonder what that would be like to have discomfort with my body?" You already know what that's like.

If you take a moment to think about it, how many times in a week while you're getting dressed do you think about how you want to present yourself that day? "Today I'm feeling a little butch. I'm going to put on my flannel shirt, and my boots, and I'm going to go down to the store and get a coffee and I'll get the paper." Some days I'm a little bit more in my skinny jeans and my Oxford shoes and my fitted shirt and I pass as a gay guy. On the spectrum of masculinity and femininity, I land somewhere different every day. But I think that's everybody's thing. I know you do it. I know people think about it. Even straight people are thinking about it.

Guillén: And yet—in thinking about it—that's precisely what makes so many people uncomfortable. I'm pleased that you're here to host Add the Words: The Movie in Boise, Idaho. Have you seen the documentary?

|

| Photo: The Idaho Statesman |

Guillén: My understanding is they had a hearing behind closed doors to change state policy so that they could arrest her.

Harvie: And she wanted to be arrested?

Guillén: Nicole LaFavour is a valiant champion of LGBT rights in Idaho and, I believe, will go down in history for her efforts, in the same way that Harvey Milk is remembered for his efforts in San Francisco.

Harvie: Anyway, I saw that clip with her co-representatives walking by her and you could see that some of them wanted to help but couldn't, while others held her in disdain. That clip really impressed me.

Guillén: How did you end up being in Boise for this event?

Harvie: Cammie Pavesic got my information from a mutual friend who knew I was a comic and told her, "You should have Ian come and help raise money to get the word out about this film and to get the film out to other festivals." Cammie wrote to me last Fall and I wrote back saying, "Yeah, I would love to." She offered to pay for my flight and hotel and I said, "No problem. I'll just come up and do it." She said, "Are you sure?" So I'm not taking a dime on this. But what I did was I had my booker book Portland and Bend. I flew to Portland and did a show on Sunday night, Bend last night, drove here today, and so I'll do the show here tonight. So I made my money there in Portland and Bend to cover my expenses. I got this invitation first and built those gigs around it.

Guillén: This might seem obvious, but why did you want to help us out here in Idaho?

Harvie: You know what? This is one of the states that's being left behind. I'm originally from the state of Maine, though I live in Los Angeles now and, as you know, California is so modern. But Idaho is being left behind. That's something Cammie and I talked about on the phone. There are states out there that have not passed these laws yet to protect LGBT people. It's not special rights; it's equal rights. There are people within states like Idaho that still don't understand that. Idaho is one of those states that's—forgive me—in a time warp.

I lived here for 14 months 20 years ago and I worked at the one gay club in the state. People used to come in the parking lot with shotguns and fire them off to scare the LGBT people walking into the club. I don't think it's like that today, but I do think that there is still a lot of education to be done here, obviously. That these laws haven't been passed to add sexual orientation and gender to Idaho's human rights amendments for LGBT people is just crazy to me: it's 2015! I have a huge special place in my heart for Boise, and Idaho, because I lived here at such a developmental time in my life and I met such incredible people here and I can't bear to think of my friends and their families not being protected. It drives me nuts! Cammie reminded me that a lot of states have equality marriage and equal rights and don't know that their neighboring states don't.

Guillén: Don't get me started on solidarity issues. Even with "modern" California, I reached out to many queer film writers and activists to try to get them involved in supporting the Add the Words movement in Idaho, and Cammie and Michael's film on the movement, and their response has been silence. It embarrasses me that—once San Franciscan queers secured their rights—they appear to have lost interest in helping others secure their's in embattled states like Idaho.

Harvie: I am one of these people who cannot bear the thought of anybody being left behind. Let's say we're out at a restaurant after a club and there's a really quiet guy in the group, I'm the one who will say, "Get in here." I can't stand the idea of anybody ever being left out. So that was my urge. I said, "Yeah, I'll come up and do some stand-up and—if that helps—great."

Guillén: Well as one Californian to another, thank you for rallying. Now, here's a somewhat difficult question. I've talked to other transgender artists about it. It's an issue I want to understand. The issue here in Idaho—as testimony revealed at the hearing before our legislature—is something of a false heirarchy of need. There's some struggle but a willingness to accept sexual orientation within the human rights amendment, and yet a complete confusion about gender. The transgender individuals who stepped up to give testimony became the excuse to justify fear.

Harvie: Why do they frighten them?

Guillén: I don't know, but let's explore this. It came home to me when one of my best friends—a good-hearted friend of mine from high school who is adamantly in favor of the Add the Words movement—said to me over dinner after the disappointing results of the hearing: "If only the transgender people could be quiet for now and allow lesbians and gays to win their rights first, then the Add the Words amendment could pass in Idaho." I didn't even have the words to express how misguided I felt she was and how offensive such a strategy would prove to be.

Harvie: It is offensive.

Guillén: Can you speak to that argument?

Harvie: If that person were in front of me, I would ask them if they remember Stonewall? Stonewall was trans women and butches throwing punches with the police. They were the people on the front line.

Guillén: As they were even earlier at San Francisco's Compton's Cafeteria riots.

Harvie: We are one family, period. It's a hard thing to speak to because I don't want to get angry about it. I just want to explain to that person that's not how civil rights movements move forward. You don't concede. You don't leave someone behind. You don't say, "No, no, no, you'll be fine. We'll come back for you later." Meanwhile, trans people have the highest rate of murders. If you want to talk facts and numbers and statistics, trans women of color in particular need these protections more than anybody else. Eight trans women this year were murdered by the end of February. It wasn't eight gay men. It wasn't eight lesbians. It wasn't eight trans men. It was eight trans women.

Here's what it's going to take to deal with trans hate crimes. It's going to take as much passion and funding as the equality of marriage movement to stop people from murdering trans people, trans women in particular. You don't move a civil rights movement forward by separating the group. That's exactly what our opponents would want us to do. It weakens the movement.

Guillén: Yet the capacity to be divided remains a real danger. Just recently in San Francisco there was a physical confrontation between transgender activists and young gay men in the Castro over an attempt to protest the mainstream gay community's complicity with white supremacy and transphobia. This is something that I've had my eye on for some time. I already knew that some lesbians feel threatened by trans women and gay men by trans men and I don't understand why.

Harvie: I haven't seen that as much. But I will say that—as a trans guy—we have so much privilege. This is just to make a point, but—if I were walking down the street and we'd never met and you knew nothing about me—how would...?

Guillén: [Jokingly, I make a clicking catcall.]

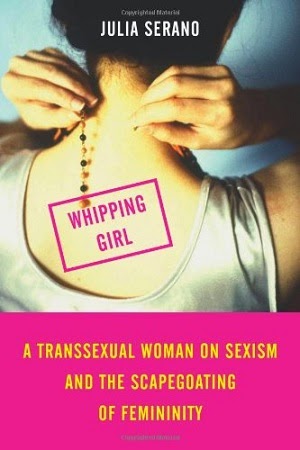

Harvie: [Laughs.] Okay. There's that. But, would you have even thought twice about what I was assigned at birth? That's a privilege that I have and it's a privilege that you have. The numbers are so opposite as to what trans guys have to go through in comparison to what trans women have to go through. There's a great book out there—I don't know if you've read it?—called Whipping Girl by Julia Serrano. She talks about how everybody fears femininity, especially when it comes from someone who was assigned male at birth and then later transitioned. She says there's a deep hatred for someone who wants to give up their male privilege. Why would you want that? It's misogynist. It's trans-misogynist. Whipping Girl speaks a lot about that, which is at the core of why gay men, cisgender men, are so fearful in particular and also why a few select separatist lesbians who—maybe of a certain age—are really adamant about not letting trans women into their spaces.

Guillén: I'm not really asking for an answer to this question. I'm simply seeking out multiple voices on the issue because I suspect it is a divisive one within our community, within our family, that is not acknowledged enough.

Harvie: Absolutely. It's a big problem.

Guillén: As a trans male, can you speak to gender parity within your own community? Is there communication between all of you?

Harvie: Yeah, everybody knows everybody.

Guillén: Do you know Jed Bell?

Harvie: I do. I know Jed Bell from Maine, 26 years ago.

Guillén: Jed was the first trans male I talked to. I realized I was afraid of trans men and I didn't want to be afraid.

Harvie: Were you afraid or you just didn't understand?

Guillén: I just didn't understand and I wanted to understand. I invited him over and told him, "I want to talk to you because I want to understand who you are, what you're about, and what your problems are within the gay community." What came out of that conversation was the realization that his transition to becoming a man was exactly comparable to my experience of becoming a man within the gay scene. He told me that what hurt him the most was the lack of acceptance, tolerance and understanding from gay males. He said he thought of himself as a gay male and looked to us for guidance. He thought he would be included but, at that time, didn't feel he was being included. I haven't talked to him in recent years so I'm not sure how he feels about those things now.

Harvie: Like many things, that tide is changing. What happens to guys who are attracted to guys who may still have female anatomy, but they're masculine? What does it say about them? They experience a shift around that process. Maybe, at first, they're confused and experience self-hate about it, but the tide is changing. For trans guys it is now becoming—I would say—even sometimes fashionable for top gay guys to have a trans male partner. A hole's a hole, whatever, bring it. Hot is hot, bring it. I've gotten that from a few guys. It's like, "Oh, right." It's becoming less important. It's easier for guys to let that go for trans guys than cisgender guys are for women.

Here's the thing: realness—of people being passable either as female or male—is way fucking overrated. It's something that people place intense importance on. When you were talking about the legislative people being scared of trans people, I'm guessing that's what this references. These are people who have not necessarily seen a trans person. And the media has done a terrible job at depicting who trans people are so that—when someone steps up—they use these frames of reference from the media that have been incorrect, such as that being transgender is a mental illness or that it's associated with pedophilia.

Guillén: This misunderstanding also supports the fulcrum of the argument that then politicizes space, specifically the reductive argument I'm hearing again and again ad nauseum about access to the contested space of the bathroom.

Harvie: Again, as a trans male, not a thing I have to deal with. I get fearful in the men's restroom because I'm afraid I'm going to be found out, but I absolutely without a doubt know that's not an issue for me walking into the bathroom, but I know it is for trans women. If a trans woman is living her life as her true self and she goes out and has to use the restroom, she's probably suffering some serious anxiety.

Guillén: I don't know how accurate this is, but I was told the other day that in the process of transitioning from male to female one of the prerequisites is that they have to go to a women's restroom even before they have transitioned?

Harvie: That's really old information. They don't require any of that stuff anymore. They used to require that you live a year as a woman before you transitioned, which was so fucking dangerous. "Go out and see if you can handle it first and risk your life for a year living your life as a woman before you really commit to this whole thing." They got rid of that and decided, "You know what? We believe people when they tell us who they are so we're no longer requiring that in the standards of care to make people do this crazy fucking thing." When someone tells me who they are, I believe them. I'm like, "Absolutely, yes, you are."

Guillén: I agree, and then I just seek to discover who you are on top of that.

Harvie: So, no, they don't require that anymore. Some really brilliant people advocated to have that removed; it was so insane.

Guillén: Shifting to tonight's screening of Add the Words: The Movie, I'm struck by how the Add the Words movement is distinguished as an ally-supported movement. It's such a different movement than the gay male movement of the '70s and '80s and it's something I can't quite get across to queers who have already earned their rights. Here in Idaho, if you're GLBT, it's dangerous to come out and be part of this movement. Not to say that there aren't brave souls who will do so, but primarily the fight is being fought by straight allies who see this—not as a gay rights movement—but a human rights movement. If you come out as a gay or lesbian or transgender person to support the movement you take an incredible risk of losing your job or losing your housing or being physically harmed. That's the point. I find this straight ally support astounding and incredibly moving.

Harvie: I'm so glad you've said that. When I was driving here today from Bend, I was thinking to myself that an ally-supported movement is exactly what is going to effect change in Idaho. Obviously, it will include GLBT people, but true change is going to have to come from families and friends of these loved ones and employers who embrace their hard-working employees. It's going to take those people who aren't at risk to bravely step up to support those who are, to open their mouths and say, "You know what? We love these people and we support them. You should do the same."

Here's the other thing: nothing ever gets done by wagging your finger in somebody's face and telling them they're a fat, bloated, white, potato-farming Republican. Nothing's going to get done that way. People are going to have to blow a little smoke up these people's ass and tell them that they have to do the right thing. But it will have to be nuanced in such a way by these allies to make it clear that this is the right thing to do. That's sometimes the only way to get that shit done.

Guillén: And I've always been a proponent of that saying Confucius had that if you want to change a culture, change its language. That's where I feel you help out as a comic. You're playing with the language by which we understand ourselves and tweaking it, by maybe even making us a little uncomfortable.

Harvie: Here's what I do. I talk more about feelings and my story and stay away from specific language that people don't yet wrap their heads around. I try to stick to feelings, like how I feel about my body. That way someone in the crowd thinks, "Hey, that's how I feel about my body too." Leaving the labels off sometimes feels subversive to me. The labels are important, but when you talk about feelings, you find more shared space. I wish I could do a show for those people at the state house and let their shoulders relax around all this information.

Guillén: Well, my feeling is that I'm so grateful that you are here, and that you accepted Cammie's invitation to come help us fight this fight. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me today.

Harvie: Thank you.