Now I've heard there was a secret chord

That David played, and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor fall, the major lift

The baffled king composing Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Well, maybe there's a God above

As for me all I've ever learned from love

Is how to shoot somebody who outdrew you

But it's not a crime that you're here tonight

It's not some pilgrim who's seen the Light

No, it's a cold and it's a broken Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Well people I've been here before

I know this room and I've walked this floor

You see I used to live alone before I knew you

And I've seen your flag on the marble arch

But listen love, love is not some kind of victory march, no

It's a cold and it's a broken Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

There was a time you let me know

What's really going on below

But now you never show it to me, do you?

I remember when I moved in you

And the holy dove she was moving too

And every single breath we drew was Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Now I've done my best, I know it wasn't much

I couldn't feel, so I tried to touch

I've told the truth, I didn’t come here just to fool you

And even though it all went wrong

I'll stand right here before the Lord of song

With nothing, nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah

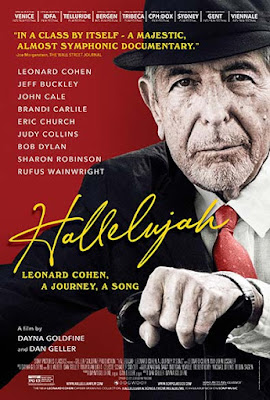

Quoting the lyrics of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” can arguably only be a snapshot in time. As laid out in Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song (2021)—Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller’s long-anticipated documentary (it took eight years to make)—"Hallelujah” was a song whose lyrics Cohen adjusted for years. Alan Light described it as “a little number he had been sweating over for years.”(1) Reputedly, the song had gone through anywhere from 80 to 180 draft versions.(2) Although it might seem that—since Cohen has been dead for nearly six years now—the lyrics of “Hallelujah” would be indisputably fixed, there remains a forward momentum to the song that suggests its intention to continue evolving, having already gone through so many transitions and varied performances within Cohen’s lifetime, subsequently shifting into a standard cover for multiple performers (at last count over 300), edging towards an ensouled anthem, and destined (I believe) to become a traditional a century or two down the line. “Hallelujah” is a song that has found and celebrates a life of its own.

As synopsized in the film’s trailer, the resurrection of “Hallelujah” from its near-death is the stuff of music legend, and as close to remedial justice as an artist could ever hope for. Five years after Recent Songs (1979), Cohen’s sixth studio album (and the third in a row that failed to do well), Cohen came down from a zen monastery on Mount Baldy, just north-east of Los Angeles, and entered into collaboration with producer John Lissauer to craft Various Positions (1984), which featured Cohen’s first recorded version of “Hallelujah.” Upon completion, Lissauer was convinced the album was going to be an important breakthrough for Cohen. Unexpectedly, Walter Yetnikoff—then president of CBS Records—hated it and refused to distribute it, even though it had been paid for. Various Positions was eventually picked up by the independent label Passport Records, and the album was finally included in the catalogue in 1990 when Columbia released the Cohen discography on compact disc. A remastered CD was issued in 1995.(3)

Despite the shortsightedness of Yetnikoff, “Hallelujah” was performed by Cohen on tour (with varying lyrics). “Hallelujah” was then first covered by John Cale in 1991, which inspired Jeff Buckley’s 1994 version. Both versions, strengthened by Rufus Wainwright’s rendition on the Shrek soundtrack (2001) helped the song gain traction. The ability for a cover of a song to, in effect, rescue and resuscitate a song seemed an appropriate place to launch a conversation with Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

My thanks to Karen Larsen, Zachary Thomson and Zahra Sadrane of Larsen Associates for facilitating that conversation during the film’s mid-June San Francisco press junket at the Fairmont Hotel.

* * *

Michael Guillén: What is the value of a cover song? What is a cover song? Why that term “cover”? Do you have insight into what is the value of a covered song? Traditionals have always meant a lot to me. I interact with several young musicians in Boise, Idaho—there’s a strong music scene there—and I’ve argued for their learning traditionals.

Dayna Goldfine: What would you consider a traditional?

Guillén: “Wayfaring Stranger”, which has been around for 300 years. It’s been sung a million different ways. It could be the subject of another documentary!!

Goldfine: There’s a documentary Bill Moyers made about Amazing Grace (1990). That’s the only other one about a single song….

Dan Geller: The value of a cover—it’s an interesting question—because most songs that you’re talking about that I would consider covered are songs where the major difference is in the musicality of the song. The song holds its own as its own emotional and intellectual orbit but the musicality will shift around it a bit. The emotional emphasis may shift a bit.

“Hallelujah” is strange because the lyrics are so prismatic in a way—they’re so complex—that those covers by different artists seem like they’re entirely different songs. Just the preoccupations of the singer—whether they’re more enchanted by the Biblical references or by the sense of brokenness, or the yearning, or the celebration—they’re so different from each other that I can’t think of another song where the covers themselves almost feel like they’re new songs.

Goldfine: Right. I probably wouldn’t be able to answer your question as a generic “what’s the value of a cover”; it’s more like “what’s the value of a cover of ‘Hallelujah’?” In an early incarnation when we were first thinking about this project, we were going to have a strand of this film where we would follow two or three artists as they decided to sing the song for the first time. We were going to watch the process that they used to make the song their own.

Ultimately, a film tells you what it wants to be and—as we continued on the journey of making this film—that strand went by the wayside; but, I think every single cover of the song that we listened to, where people have really thought about it and made it their own, it’s a unique creation. I don’t think Brandi Carlile’s version is the same version Eric Church sang spontaneously at Red Rock because he was feeling blessed that night.

Geller: Or even how Leonard covers his own song with different lyrics along the way. The way he covered his own song—it’s certainly seen in the handful of video covers that are in the movie—they almost look like he’s singing a completely different song for a very different reason in each of those. That’s one of the reasons—as we got deeper and deeper into the movie—why we felt that the songwriter and the song, his preoccupation and the song he wrote and kept rewriting, were so twinned up together. To watch his own covering of his own song evolve in that way was startling. I hadn’t seen that footage before. We knew him from either hearing the original recording or seeing the concerts at the Paramount late in his life. When these other versions kept popping up while we were doing the research, it was startling to me; I had no idea.

Guillén: It was a startling pronouncement in the documentary when Cohen admitted he wanted the song to become secular. That was a nice moment in the film because it made me think, “Oh! He chose to take it out of that holy realm.”

Goldfine: Isn’t that cool? At a certain point he wanted to bring the song back down to Earth.

Guillén: I understand that the structural traction of the documentary was based upon Alan Light’s The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of "Hallelujah" (2012)?

Goldfine: Not so much the structure because in a lot of ways the film just jumps off from the book. But Alan’s book was inspiring, because—basically, knowing that someone could get 250+ pages out of this song—gave us heart that we could probably do a film. But his book really does intertwine the Jeff Buckley and Leonard Cohen trajectories with the song and our film has a section of Jeff, but that’s it.

Geller: But it was the inspiration, certainly. And Alan became a consulting producer and advisor, and also introduced us to all sorts of people. In many ways it was the depth of Alan’s book that was inspiring. It wasn’t just a simple sketching of “Gee, interesting that this song was rejected and then went on to heights.” It was the depth with which he approached the book that informed us that our film was going to be possible.

Guillén: Language is a funny thing, y’know, particularly in its false dichotomies—the holy "and / or" the broken—whereas my appreciation for Cohen over the years since I was a teenager has always been that it’s not an either / or proposition we’re talking about when accessing the poetry of Leonard Cohen, which is holy and profane at the same time. That’s what I love about his work. There’s no “or” to fiddle over. Any comprehension of his work must embrace and encompass both.

I could say the same thing about “Hallelujah.” People want to say, “I’m singing it in a sexual way” or “I’m singing it in a religious way”; but, neither approach really matters because the listener, the wild card, is going to take the song as they understand it anyways. For someone who’s being chaste, “Hallelujah” might be sexy beyond belief in its lyrics alone, no matter how its sung or how—as you said, Dan—its musicality is interpreted.

Did the two of you ever get to talk to Leonard Cohen in person?

Geller: We did not. And Alan’s advice was, “Don’t ask for an interview because you’ll never get it. Then they won’t even consider letting you do the movie.” The point of Leonard’s life was, “Leave me alone. I need to concentrate on writing what I can.”

Guillén: Your film had a wonderful metaphor. I don’t know if he said it or you two said it about reaching an older age.

Goldfine: Leonard said, “I’m not saying that 70 is old age, but it’s definitely the foothills.”

Geller: The other thing he said is that it’s indisputably not youth.

Goldfine: But he said there’s a pressing sense—I mean, these aren’t his exact words—but, there’s the pressing sense that one needs to complete one’s work. I thought that was so beautiful.

Guillén: That’s where I am!! On the edge of 70, I identify with that so much. I live in a valley surrounded by foothills that every winter—when they’re covered with snow—I’m feeling. I find myself hiking in these foothills. It’s a liminal space conducive to subjectivity. I’m not quite old, and I happen to think I’m still good-looking…. [Laughter.]

Goldfine: [Laughter]. You arrrreeeeee…!!

Guillén: Oh, thank you!!

Geller: And you dress well!! [Laughter.]

But getting back to what you were asking about lyrics being “ands” and not “ors”, and how you interpret it, there’s a moment with Rabbi Mordecai Finley that’s not in the movie but was in the interview we did with him. We were going through the verses of “Hallelujah” together, just so I could understand his take on some of it, and we came to that verse:

Remember when I came in you

And the Holy Dove was moving too

He went on about how that was right out of Medieval Jewish literature, but I said, “Rabbi, that couplet is about sex.” “No it’s not,” he said. I recited, “Remember when I moved in you and the Holy Dove was moving too? That’s about having sex.” You could see his eyes pop. “Oh my God, I never even thought about it that way,” he admitted.

That’s to your point that one reason “Hallelujah” can be sung at weddings, or funerals, at all sorts of different events, is because you can approach the song on your own terms and get from it what you want; but—if you really look at the song—you can approach that same lyric and say, “Well, what else is it trying to say?” And it will be saying a lot of things. Every single line will be saying a lot of things, inviting you in to multiple interpretations.

Guillén: As a teenager discovering Cohen (largely through Judy Collins singing “Suzanne” and then getting caught up in his published poetry), I steered through puberty reading sensuality—if not sexuality—into all of his spiritual phrasings. The importance of that fusion became seared into my sensibility.

Goldfine: Maybe halfway through the film, Sharon Robinson says that Leonard conflated the feminine with spirituality. Leonard does this riff on how, y’know, this is something we drive towards, the sexual impulse, but it’s the other side of the spiritual impulse and this sense of wanting to get at the bottom of the meaning of life. He constantly twinned those two forces.

Guillén: Which brings us to his understanding that his poetry was responsive to or informed by the bat kohl.

Goldfyne: Which Rabbi Finley articulates as the “feminine voice of God.”

Guillén: That quality of the bat kohl in Cohen’s poetry was influential upon me as a young person and, admittedly, a presiding guide to my own writing. Authors that I sought out after Cohen, such as William Goyen, also wrote with a fusion of the sensual and the spiritual.

A song is like a room that you walk into that you’re thinking of renting for a while. What are you going to put up on the walls? What color are you going to paint the walls? What will you do to make this room yours? It’s the same with a song—and is part of my interest in covers—is how do you make a song yours? What is necessary creatively to make a song yours? How will it be different than how others sing it?

The variance of how one can interpret a song has preoccupied my consciousness since I was a child. We were migrant laborers and I grew up singing in the fields, or listening to friends and family singing in the fields. My mother had a beautiful singing voice and she would sing while we were working and—inspired by her—sometimes I would sing. I remember one time this guy we were working with commented, “You sing too slow.”

Goldfine: Interesting. What does that even mean?

Guillén: Exactly! But it hurt my feelings at the time and I protested, “No I don’t. It’s just the way I sing.” Then someone else actually supported me and said, “He’s singing that song absolutely okay. Leave him alone.” But then that made me wonder: was I singing slow? And, if so, why?

Goldfine: I don’t think there’s a rule. There have been two cases where this film has shown at festivals. The first was in Denmark, in Copenhagen, and one of the programmers found three Danish musicians to perform after the screening and sing various versions of Leonard Cohen songs. This one young woman sang, “That’s No Way to Say Good-bye” and it was a very different “That’s No Way to Say Good-bye” than Leonard would have done, but it was a poignant version. And then this last Sunday at the Beacon Theater in New York Amanda Shires [website]—who’s a country crossover who idolizes Leonard—she sang “I’m Your Man” and played it on her ukulele. It was unbelievable. I loved hearing a woman sing, “I’m Your Man.” It was completely distinct from how Leonard would have sung it.

Geller: There are some artists where the original recording of what they did was so specific to the entity of the song that it’s almost impossible to think that anyone can do a version that would match up. With the exception of Cocker doing “With A Little Help From My Friends”, pretty much everything in The Beatles catalog you cannot find any cover that equals that original. It’s the sonic environment that they created, the way they sang it, everything, it just can’t be topped. Cohen’s different because the words are so deep and so important and offer so much possibility for interpretation. I think there are plenty of covers of his songs that are every bit as good as the original versions.

Goldfine: Why would we even need to go, “This one’s good. This one’s not good. This one’s better. This one’s not.” They’re all valid.

Guillén: Because they’re doorways. Each song is a way to enter the body of Cohen’s work.

Goldfine: But what I was going to say is that for me the word would be that they’re every bit as valid, as opposed to good.

Guillén: Yes. Again, emotional truth.

Goldfine: Exactly.

Guillén: The documentary has such a wonderful cast of talking heads, some who I knew, some who I didn’t know. I was delighted to see Rufus Wainwright—because I adore Rufus—and I had totally forgotten that his version of “Hallelujah” was on the Shrek soundtrack. But I was also noticing significant absences that I would have included if I were a filmmaker and only because I am caught up in my own mythos of Leonard Cohen. He’s not only a direct influence on my life as a writer but that influence has been continual. I’ve read everything he’s written. Read everything I could get my hands on that was written about him. Listened to every song he’s sung and any covers I’ve known about. Jennifer Warnes.

Goldfine / Geller: [In unison] She’s the one!

Geller: We couldn’t get her.

Goldfine: We tried to get her.

Guillén: “Famous Blue Raincoat” was the album of Cohen covers that brought him back to me. I had set him aside as the poet of my youth, feeling I had to move on, but then Jennifer brought out her album “Famous Blue Raincoat” and I felt, “Oh my God!!”

Goldfine: Believe me, we tried.

Guillén: I had no idea that she had been a back-up singer for him until your documentary. I knew she had backed up Roy Orbison, but I didn’t know about Cohen.

Geller: Our inability to get her to talk on the documentary was a combination of things. First, it was too close after Leonard’s death when we approached her; she, among others, really needed to hibernate a bit with their feeling about what that had been like. And she’s very shy as well. As far as people we went after, she was the only one who declined.

Goldfine: Obviously, she was front and center when we first started thinking about who to approach. Though I have to say that Sharon Robinson is also a great back-up singer and then a collaborator with Cohen on many albums.

Guillén: I was so glad to be introduced to Sharon through your documentary.

Goldfine: She’s amazing. John Lissauer was a very early interview as well, back in 2016, and we knew he was friends with Jennifer and I remember saying, “We would like to interview her” and he said, “I’ll be surprised if she does it. She’s very shy.” At that point Leonard was still alive so we put it on a back burner and started asking other people. Then Leonard passed. I had reached out to Roscoe Beck, who was Jennifer’s ex-husband, and who was in the process of producing her last album, which came out a couple of years ago. I asked if he would sit for an interview and he said, “You don’t want me. You want Jennifer.” At that point I wrote back and said, “Indeed. But everyone tells us she’s too shy.” He said, “Write me a letter and I’ll forward it to her.” He was generous enough to do that. She still said, “I just don’t want to. My memories of Leonard are here and I’m not really ready to articulate them.” As a filmmaker, I think it’s very important to respect that. When a potential subject of an interview tells you clearly and articulately, “I don’t want to do it”, I think it’s only fair as a filmmaker to go, “I respect that.”

Guillén: What about Cohen saying that people should stop singing “Hallelujah”?

Goldfine: I agree with “Ratso” that he was kidding.

Guillén: Kidding, perhaps, but also not kidding? I don’t believe in either / or positions. I think multiple feelings are going on at the same time.

Geller: I think so too.

Guillén: The other person whose absence I noted—though you did have one image of her—was Joni Mitchell.

Goldfine: Because we were looking at it through the prism of “Hallelujah”, it narrowed our choices. But it was a gift to us as well because it meant we didn’t need to be trying to make the definitive Leonard Cohen bio pic. Every time we thought about who we were going to interview and what kind of things we were going to include, it was always, “How does this fit into the prism of ‘Hallelujah’ ”? And, of course, his relationship with Joni was in the ‘60s and it wasn’t that long-lived, so it didn’t make sense to include her.

Guillén: Which I accept and understand, but more I was thinking about “Rainy Night House”, the song she wrote about him.

Goldfyne: And “Case Of You”.

Geller: If you can get us the interview, I’ll be down in a second.

Guillén: I’ll see what I can do. [Laughter.]

Goldfine: But then again, it didn’t make much sense. Jennifer was for sure.

Guillén: Well, all the more reason to congratulate you on the strenuous work you did obtaining the archival footage. I’ll give you a classic reaction, because I can only have a personal reaction to this film. Your press notes have excellently laid out the process of making this film and I will borrow from that for review, but for me your film was just all so personal. I had always heard that Leonard was a ladies man, a serial amoreaux. I monitored these different affairs he had and the songs that came out of them. The archival footage you presented that I loved was when he was talking about how when you get older as a Jewish man, you change your name. He was talking to this woman about how he would change his name to September. He is so beautiful and so sensual in that sequence and the smile on his face is so seductive. You could see how he was seducing this woman and how irresistible he was. I could see how women would fall in love with him.

Geller: He’s like a cat toying with a mouse.

Guillén: Exactly. And he does that a lot actually.

Goldfine: I love that footage.

Guillén: Can you talk about where you got that footage. It enfleshed him.

Goldfine: We had seen that footage early and catalogued it in our minds and also in our notes on archival footage.

Geller: That’s CBC footage.

Goldfine: But it wasn’t until we were fortunate enough to sit down with Leonard’s rabbi, Rabbi Finley, in L.A. over coffee that he reminded us of that footage and unpacked it for us in a Jewish way. It was like, “Oh my God. This gives us a whole other layer.” Then when we got back home after that interview with Rabbi Finley and revisited that footage, it was unbelievably rich footage in terms of the way Leonard was flirting mercilessly with this woman. She was in his palm.

Guillén: As was I!! That’s what I’m saying. I’m so grateful that you found and incorporated this CBC footage because I felt that I was being seduced by Leonard Cohen.

Geller: And also being toyed with, because when he says September—and he’s not fessing up that it’s a Jewish rite of passage—when he says, “I’m also thinking of getting a tattoo” and that has a double meaning. First, we’re talking about (at that point) less than two decades away from Auschwitz, right? A tattoo on a Jew means something very different. The other is in the orthodox Jewish tradition, or in the priestly Cohenim tradition—because the Cohens are the priestly tribe—tattoos are forbidden. If you have a tattoo, you cannot be buried in a Jewish cemetery, right? So, whoa, he’s just throwing these little bombs at her, figuring she has no idea. Most people don’t have an idea what he’s saying in such a simple line. And then, of course, she says, “Where are you going to get the tattoo?” and he says, “Over on York Street.” [Laughter.]

Goldfine: Because he’s always one step ahead of her. But, again, I thank Rabbi Finley so much for unpacking that scene for us because it might have made it into the film without that, but—having Rabbi Finley explain in this very beautiful, graceful way about what it really meant to Leonard to say he wanted to change his name to September—it allowed us to use that scene in all its comic but rich context.

Guillén: You had to negotiate a difficult transition when you began to talk about Jeff Buckley reintroducing “Hallelujah”. As I was watching the film and the focus shifted to Buckley, I winced because—I have to be very honest—I never cared for Jeff Buckley or his cover of “Hallelujah”. It never did anything for me. I never liked his version of the song.

Goldfine: So did you agree with him when he said he hoped Leonard would never hear it?

Guillén: Well, I thought he was being a bit precious.

Goldfine: No, I think he was right. He was actually quite humble.

Guillén: But, truthfully, how could Leonard not hear it?

Geller: Right. I think he was just saying he hoped Leonard would never hear it. When he finally fessed up and said, “It sounds like a boy singing it”, there’s truth. I think he knows vis a vis Leonard at that stage in the early 1990s that it would be hard to measure up. Musically, it’s gorgeous.

Guillén: As your documentary points out, and as is well known, Buckley’s version is how most people know this song; but, when the documentary started going off on this, I thought, “Oh-oh. Is that all for Leonard? Because I’m not done with Leonard! I want Leonard.” I thought the way you paced and abbreviated the focus on Buckley was masterfully edited. You offered just enough Buckley that I actually felt for him this time around and actually appreciated what he had done with the song.

Geller: Good.

Guillén: The headline of his drowning in the river was tragic, and it made me wonder if this song would have become what it became had that not happened? There’s a mystery touched upon in your documentary about that song. “Hallelujah” is going to become a traditional, as I mentioned before when talking about “Wayfaring Stranger”, which is already 300 years old. “Hallelujah” is going to become a traditional sung 300 years down the line, 400 years down the line, people are still going to be singing this song.

Goldfine: Both Clive Davis and Rufus—actually, almost every single artist that we interviewed—said that if it’s not part of the Great American Songbook, it will be.

But the one thing I wanted to say about Jeff was that was the hardest section—not so much to edit as a sequence—but to figure out how much to go there and when to cut back. The very first version of the Jeff Buckley “chapter” of the film (if you will), was twice as long. We had to find a way to pare it back.

Geller: Bit by bit by bit.

Goldfine: It took a long time to get it to be the right balance.

Guillén: I often feel that editing is not given the due it deserves. It is the hard part of making a film, especially when you’ve gained access to so much information. After the Buckley chapter, as you phrased it, the documentary then explores the popularization of the song via “American Idol” and Shrek, which admittedly began to make me feel a little bit uncomfortable because of the dangers associated with the commodification of a song. It’s like all the conflicted feelings I have about the commodification of Frida Kahlo.

Geller: Commemorative mugs!

Guillén: Refrigerator magnets! But then—again, quite skillfully—you brought it back to Leonard and how he did the song, showing what the song really was.

Goldfine: Thank you.

Geller: We had the let the air out of the balloon a bit because—after blowing it up like that with the “American Idol” sequence—we had to let the air out carefully so that you don’t feel a sudden disjuncture and could be let down from that manic crazy moment when the song is at number 1, 2 and 36 on the U.K. charts. There were some corners to turn that we weren’t immediately successful at first, but we kept at it.

Goldfine: Thank God somebody interviewed Leonard right at that moment in 2007 or so when the song was in three places on the charts. I love that he says, “Maybe people should stop singing it for a while” and he has this little smile on his face. Ratso says he was kidding. Who knows? Other critics have said he told people not to sing it anymore.

Geller: You’ve brought up something, Michael. When we make our films, we hope that they last for a while and some of them have lasted for decades now, which is great, but I hadn’t thought until you just mentioned it that the song is likely to become a standard and that might give a chance to this movie to be a resource for people for however many years down the line if they’re curious about this song that is a standard, a portrait of how it came to be, and the man who made it. That just made my day thinking, “Maybe this film might last for a good long while.”

Guillén: And there’s value to that. I’m just about to hit 70 and I think, this guy, this song, has been in my life since I was a teenager. His poetry helped me through my early love affairs. His poetry told me what a love affair was supposed to be, or what a poetic life was supposed to be, so that when I first visited Manhattan, I had to stay in the Chelsea Hotel, and when I had the chance to meet Joni Mitchell after a concert in Memphis, I lingered at the stage door to meet her. In other words, his has been a longbody influence. What is speaking to me now—that you have so elegantly portrayed in your documentary—is that Leonard Cohen, ever since he was a young man, wanted to be an elder.

Goldfine: Isn’t that unbelievable?

Guillén: And approaching 70, I too long to be an elder in the full and resonant meaning of the word.

Goldfine: I don’t know if it’s ever chic to say that you want to be an elder, but for him to say it in 1974, at the age of 40, in a conversation with Ratso Sloman….

Guillén: And perhaps he shouldn’t have said it at 40?

Goldfine: Why not?!

Guillén: Because he wasn’t an elder.

Goldfine: No, he wasn’t saying he was an elder. He said, “I would love to become an elder. I hope I have the good fortune to be able to become an elder.”

Guillén: Okay, that I accept. And it tracks with what I’m currently feeling. I tell myself, “You made it through AIDS. You made it through Trump….”

Geller: [Laughter.] You’re still making it through Trump!!

Guillén: Right. We just had that horrible incident of the men arrested in northern Idaho who were on their way to a gay rally to cause horrible damage and I think, “Another near miss.” But what Cohen keeps giving me and making me think—specifically through what your documentary presents to your audience—is, “Look how elegant he is. Look how humble he is. Look how loving he is. Everyone who collaborates with him, who works with him, loves him.”

So, first, as a young man he taught how to have a love affair and now he’s teaching me how to be an elder, how to be gracious to the young. What’s holy about his graciousness is what the Native Americans would call the longbody. When he was young, it was as if he was already old. And when he was old, he related to the young. That holiness is what I believe people respond to in Leonard Cohen. It’s a palpable, physical, visceral response to his writing and his music and the experiential arc of his life, which served to create “Hallelujah”. I can’t get that song out of my mind since watching your film. I’ve been singing it under my breath for about 69 hours now. [Laughter.] And I don’t even know all the lyrics so I keep singing the same incomplete phrases over and over!

Goldfine: When the film played at the Beacon on Sunday night, there was a mini-concert afterwards and the concert promoter set up who was going to be in it. There was Judy Collins—that was an obvious choice—so that when the curtain came up after the film she sang “Suzanne” and then it was Sharon Robinson, Amanda Shires, and then this promoter goes, “Trust me, be open-hearted about this, I think this guy named Daniel Seavey who’s in a boy band and who came to fame singing ‘Hallelujah’ on ‘American Idol’ should sing ‘Hallelujah’ at the end of this show.” I can’t speak for Dan but I was like, “You’re going to have someone come out and actually sing ‘Hallelujah’ after this film’s over?!” Daniel came out—he’s like 22, 24 years old—and he hit it out of the park. He brought the house down. He made that song his own.

Guillén: That’s it! That’s what I’m approaching when I talk about the cover, or when I talk about traditionals, what I’m trying to say to my young musician friends in Boise, “It’s not really about you. It’s not about how you’re going to interpret the song. It’s not about how you’re going to phrase it, or pace it. That’s not what the true value of a cover is. It’s that the song is holy. It covers time. It’s about time. You’re the steward. You’re a speck of time in the life of the song. And don’t you want to be a part of it? That’s where ‘you’ come in. That’s where—when you match the holiness of the song—you own it and it becomes yours as it becomes anyone’s who willingly serves as the steward to the holiness of the song.”

I’m so grateful that you chose with this film to focus on such a powerful song. But I was surprised when I reviewed your press notes that you claimed to have never done any film about music. What about Ballets Russe (2005)?

Geller: Well, there was music in that but I wouldn’t say it was a movie that was examining music in and of itself.

Goldfine: Early on, when we were just starting to toy with this idea, we were fortunate enough to be on a festival jury with Morgan Neville who’s made a lot of music docs….

Guillén: Good ones!

Goldfine: Really good ones. He’s a great filmmaker. We pitched this idea and he offered to come on as a DP and that gave us some street cred because—even though we thought we could make a music doc based on our past work—the world didn’t necessarily agree that we could.

Geller: It just opened more doors. His participation was a validation. By Morgan Neville saying that these filmmakers have the chops to do something like this, for people in the music world who might not have been familiar with us, it helped. People in the dance world know who we are. People in the art world know who we are. But we were entering a new terrain.

Guillén: And I believe it’s becoming an increasingly popular genre, largely because of my generation, our generations, people are more interested in what influenced us in our youth? Here I am now, pushing 70, what made me who I am now that I can look at these foothills dusted with snow and have a poetic, aesthetic arrest? It was music. Music helped me become myself and continues to do so through every year I’m alive. What songs mattered to me? What songs matter to me now?

I’ve been saying for years that as I grow older my films of choice are documentaries. They’re the most interesting stories because they’re real stories.

Goldfine: You can’t make up anything better.

Guillén: Right.

And I think people are more interested now in the musicians, the artists, the art of crafting songs, and your documentary is attractive for providing the fulcrum of one song to shed light on the man who wrote the song and on the art of songwriting itself.

Goldfine: It definitely allowed us to narrow and hone in on one aspect of Cohen’s artistry. In some ways it’s a revisionist history because so many people have idolized the Marianne-Leonard relationship but I feel our film is saying, “That was one thing, but, you know, there was Dominique.”

Guillén: And though you use “Hallelujah” as a fulcrum to leverage insight, your film is not just about “Hallelujah”. You sample many of Cohen’s songs.

Geller: There are 22 of his songs in the film.

Guillén: Which was a great relief because I was concerned that you were just going to keep playing “Hallelujah” over and over again until I would go crazy and have to rush out into the lobby to stuff popcorn into my ears.

Goldfine: We didn’t know we were going to do 22 other songs, but we also weren’t completely upfront with Robert Corey, the head of the Cohen estate, who said, “If I would have known eight years ago that you were going to talk about 22 other songs, I don’t know if Leonard or I would have allowed you to do this project.”

Geller: But we didn’t know when we approached it! But as we started playing with it, to understand “Hallelujah”, you need to know “Who By Fire”. To know “Who By Fire”, it would help to know a little bit on the other side, like “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On”, just to see the different elements of Leonard. Then, because the film does extend to late in his life, “Tower of Song” becomes important. It’s all about mortality, and aging, and where you are in that tower. Bit by bit we began to get further into debt. [Laughter.]

ENDNOTES

(1) Alan Light, “Broken Tablets”, MOJO (January 2020, pp. 70-71).

(2) Wikipedia entry on “Hallelujah”, accessed August 5, 2022: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallelujah_(Leonard_Cohen_song)

(3) Wikipedia entry on Various Positions, accessed August 5, 2022: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallelujah_(Leonard_Cohen_song)