Triple-crown award winner Ellen Burstyn claims she realized as a young actress that she wouldn't be able to rely on her looks if she wanted to have a career, and yet at a spry 83 years old, Burstyn is undeniably gorgeous. A last-minute announcement (only three days before the festival) and a last-minute venue change to the Victoria Theater may have accounted for the sparse audience (75-100 people) for the onstage conversation with Ellen Burstyn, the recipient of the Peter J. Owens acting award for the 59th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF); but, though at first seemingly disappointing, the small audience actually allowed for a closehand intimacy with a forceful talent. Had this event been at the Castro Theatre, it would have been an altogether different animal.

Peter J. Owens (1936-1991) was an actor, a film producer, a philanthropist and an important supporter of the San Francisco Film Society, who remain grateful to Scott Owens and the entire Owens family for continuing his legacy by endowing this award, which honors an actor whose work exemplifies brilliance, independence and integrity.

In his introduction to their onstage conversation, SFIFF Executive Director Noah Cowan noted that when it came to Ellen Burstyn, it was difficult to avoid her "triple crown". She's one of the few performers who has won an Emmy®, an Oscar®, and a Tony®. In reviewing her work, he found her performances daring, gutsy, and impressively diverse.

Arriving to the Victoria stage after the festival's clip reel, Burstyn joked, "I feel like I've just seen my whole life pass before me."

Cowan stated that—in researching Burstyn—it quickly became apparent that her outstanding career had not been one of "comebacks" but, rather, a consistency of exceptional work decade after decade, film after film. He wondered if that hadn't come about because fame came later for her? It didn't arrive until she was 42 and won her Oscar® for her performance as Alice Hyatt in Martin Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974). He queried how important her formative years had been in creating the hardworking actress she is today?

"I never wanted to be a movie star," Burstyn replied thoughtfully. "I always wanted to be an actress. I figured out pretty early on that—if I depended on my looks—I would have a short career. I had to learn how to be an actress. It took me a while to figure that out. At a certain point I saw the work of actors like Marlon Brando, Jimmy Dean, Kim Stanley, Geraldine Page and noticed that they knew something I didn't know. They were doing something I didn't really understand. I left the career I had in Hollywood for New York and studied with Lee Strasberg. I learned the art of acting, which is a different thing than a superficial presentation of yourself."

Cowan noted that the Strasberg School remained of importance in Burstyn's life. Along with Martin Landau and Al Pacino, Burstyn is one of the chief mentors at the school. He asked her to talk a bit about what studying with Strasberg brought to her and what the school brings to other actors?

"First of all," Burstyn answered, "there's the Actors Studio, which is a workshop for professional actors. You audition to get in and, once you're in, you're in for life and you use this studio whenever you need to for whatever you're working on. Then there's our school, our Masters Degree program at Pace University in New York. That's an accredited school where you get a degree. My training was at the Actors Studio with Lee. What I learned from him—I can't say it changed my life, it made my life—because my values weren't very developed until I went to him. He's the one that really introduced me to depth living, I would say, just because of the intention of what you're doing and your willingness to go deep. I didn't know about that before and I did learn it from him.

"When he died, by that time I was a member of the board and I was one of the moderators (he had asked me to be one in the '70s). We say moderators, some people might say teachers, but we like to keep a little distance from the teacher-student relationship when we're talking to actors with careers. After he died in the 1980s, I ended up being a president along with Al Pacino and Harvey Keitel, and currently I'm the Artistic Director and have been for quite a while. I moderate every Friday that I'm in town. The Actors Studio is the place I learned how to be an authentic human being and, therefore, qualify as an artist. I feel that there are very few places in the world that are free to actors to give them what is essential for them to practice their craft, which is the stage and an audience."

Cowan described her performances, as in The Exorcist and Alice, as iconic moments of '70s cinema and commented on how she didn't seem to care what genre she worked on, attracting roles that ran the gamut from dramatic to light comedic to horror and thrillers, which he deemed unusual.

"Is it?" Burstyn responded, surprised. "I never thought, 'I'm going to do this genre and not do that genre.' I can do comedy when I'm offered it. And I can do drama when I'm offered that. It's never been important to me what kind of film it is. What's more important is what the role is and what the film says, what the stories are."

When people discover Martin Scorsese directed Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and they watch it, Cowan assessed, they discover something different than what they associate with Scorsese, because it was actually Burstyn who made that film happen and brought Scorsese on to the project. Cowan asked her to recount how all that happened.

Burstyn: "I was shooting The Exorcist in New York and the dailies were going back to California, to the President of Warner Brothers at the time and he called my agent and said, 'We want to do another movie with her.' He sent me all of the scripts that they already owned. This was in the 1970s when the Women's Movement was just coming alive. Women were going through the transition where they were realizing—as my character said in Alice—that 'I'm going through my life and not some man's life I'm helping out with.' That was the transformation of consciousness that was happening at the time. All of the scripts that they sent me were the old way: women were either the loyal wife who stayed home when the hero went out to save the world and then—when he came home—she had hot chocolate waiting for him; or she was raped and beaten and a victim; or she was a prostitute with a heart of gold. They were all pretty stereotypical characters so I told them I didn't want to do any of those. I went out looking for a script that could reflect a woman as I understood women to be: as full human beings.

"I came across Alice and I brought it to Warner Brothers and they said, 'Let's do it. Who do you want to direct it?' They asked me if I wanted to direct it and I said, 'No, I'm not ready to direct and act at the same time, thank you very much.' So they asked, 'Who do you want?' I said, 'Someone new and exciting.' I phoned Francis Coppola and asked him who was new and exciting and he said, 'Look at a film called Mean Streets.' It had been made but not released. Warner Brothers owned it so they played it for me. I asked for a meeting with Marty and he came in—this very nervous little guy—and I said, 'I saw your film. I really liked it. But Alice is a film that's told from a woman's point of view and—in looking at your film—I can't tell if you know anything about women? Do you?' He said, 'Nope, but I'd like to learn.'

"So we did it and, of course, I had no idea that I was hiring one of the great film geniuses. We rehearsed and, in rehearsal, we did improvs and they were recorded. At the end of the day the ones that we liked were sent to the screenwriter, but there was a nod to all of us. We all created that film."

Cowan wondered if she felt not enough has changed for women in the film industry since Alice; if she felt there had been progress?

Burstyn: "I think there's been progress but it's been slow, as progress always is. Look how long we've been trying to outgrow racism in this country. It takes time. There's progress but there's a long way to go. The same with women. We live in a patriarchy, let's face it. To make a change in the patriarchy towards equality of the sexes takes time. I was just in Stockholm this year and I noticed there were a lot of women in executive positions. I mentioned it to one of the women and she said, 'Yes, we've had gender equality for two generations now.' I said, 'How has that worked out?' and she said, 'Really good.' I said, 'Why is that, do you think?' She said, 'Well, what we've discovered is that women work for consensus and men work to win.' Isn't that good? Don't we know that to be true? So it's run very well over there."

Cowan pursued the rumor that Burstyn was planning to direct a film.

Burstyn: "There was a script that I was sent to act in and I had just been thinking, 'Y'know, I've never directed a film. I meant to do that and somehow let that get away from me.' They sent me this script called Bathing Flo, which I really liked, and I said, 'Definitely. I want to do it.' They said, 'Well, who would you like to direct it?' It was like an answer from the Universe! I said, 'How about me?' They said yes, so we're in the process or raising money, which I want to tell you is the worst part of the business than I ever imagined. We've been trying to raise money for a year. We've come close but it hasn't happened yet. We currently have a financier who's interested and will give us his final word later this month."

As she gears up to direct, Cowan inquired how it has been to take direction from so many great directors?

Burstyn: "It's wonderful when you work with someone like Darren Aronovsky, who I adore, he's so smart and so kind and so good. I remember one scene we did in Requiem For A Dream (2000). We always did several takes and they would always vary. We finished a scene and he came up to me and said, 'Okay, we've got that in the can'—at which point he would usually say, 'Let's move on'—but, this time he said, 'Let's do one more and do whatever you want.' His saying that freed me to do something I had not done in any of the takes that is the take that's in the film. It's such a good lesson for directors: to take all the obligation off the actor or actress and just let it go, let it rip, and very often that inner motor—whatever that thing is that we have inside—suddenly gets released and something unexpected comes. I consider that a really good director."

Cowan asked: Did you know what you were getting yourself into when you accepted the role of Sara Goldfarb in Requiem For A Dream?

Burstyn: "I turned it down. When they sent me the script, I read it and I went, 'This is the most depressing script I've ever read in my life. Who wants to pay money to see this?' 'No,' I said to my manager, who was then my agent, and she said, 'Well, before you say no, look at a film called Pi.' Pi was Darren's first film. I said, 'okay' and put it on and it was not even four minutes, maybe four minutes at the most, and I went, 'Ah, I see. This guy's an artist. Okay.' So I called back and said, 'I'm in.' Then I met him and fell in love.

"While filming Requiem, I had the great good fortune of having Darren's mother on the set every day and that's her accent I'm doing. Darren's mother and father were on set every day. When Darren did Pi, she was the caterer because he couldn't afford to hire a caterer. They're wonderful people. Darren's father is a professor and she's a teacher too. I would talk to her every morning and she would help me get into not only the accent but the mannerisms. Basically, Sara Goldfarb is like all of us. She had desire to be more, experience more, be loved, be looked at and seen. Those are rich things to play with and to work on."

Cowan noted that toggling between stage, screen and television has been the hallmark of Burstyn's career. Aware the Actors Studio grounded Burstyn in very specific ways for whatever she was doing; he nonetheless wondered if there something different about those three mediums for her in how she approached them? Do they inform each other?

"The real work of acting," Burstyn reminded, "is an inside job. That is the same in any medium. The expression of it might be different. I remember this moment—it was one of my favorite moments making a film—in The Last Picture Show (1971). There's a scene where I'm sitting in a chair looking at television and thumbing through a magazine, bored. My husband is sitting there asleep and I'm bored! Then I hear my lover's car drive up. Yay! I get up and run out of the room I'm in. It's a tracking shot with a camera following me. I get into the other room to open the door ('Yay, I'm going to see my lover!'). I open the door. My daughter's there. Damn! It's not my lover; it's my daughter. But wait a minute. That was my lover's car. My daughter just got out of my lover's car. She's in tears. Oh … they had sex. Oh, my daughter's not a virgin anymore. Oh, poor thing, come here, honey.

"That was a scene with no lines, okay? I say to Peter Bogdanovich, 'Peter, I have eight different moments from here to the door and no lines.' He got this impish smile on his face and he said, 'I know.' 'Well, how the hell am I supposed to do that?' He said, 'Just think the thoughts of the character and the camera will read your mind.' Yeah. So you can do that with movies and television, but that won't work on stage. But what does work everywhere is to be real. If you're real, the audience gets it, whatever it is."

"Do you have a preference?" Cowan asked.

"I love the stage," Burstyn answered without missing a beat.

"Why?" Cowan pursued.

Burstyn: "The rehearsal process is so interesting. To go into a great play like, for instance, my favorite play I ever did was Long Day's Journey Into Night. To really go into that character in that play, and the history of Eugene O'Neill and that family and the things they were doing to each other, what they represented, it's just such a profound experience. To me, the rehearsal period is the richest time. The performance of it becomes like another life you're living; like you have an alternate life. The communication that happens with an audience; there really is an exchange of energy, thought, feeling, emotion, and you get it. The audience gets it when you get it."

Cowan queried whether there was any character, any stage persona, Burstyn still felt she wanted to play; that was still inside of her?

Burstyn: "I still want to play Mary Tyrone. I never got to do her in New York. I hate every actress who plays Mary Tyrone in New York. I saw Vanessa Redgrave do it. She's one of the greatest actresses in the world and I adore her, but I almost threw tomatoes at her. Now Jessica Lange's doing it in New York. [Scowling] Jesus! I tell myself, 'Life has disappointments.' "

Cowan observed that Burstyn has been part of a movement that has happened in the last few years where long-form television has seized the zeitgeist by recently portraying Elizabeth Hale on five episodes of the Netflix series House of Cards. He expressed that it felt like she had come full circle as much of her early career had been on television. Yet now so many people know her because of House of Cards, which has had a huge public cultural impact. He asked her for her thoughts on the popular rise of narrative seriality on TV?

Burstyn: "When they released the current season so you could stream House of Cards that weekend at the beginning of March, I went out to walk my dog at 7:00 in the morning and everybody in Central Park had seen the full season! I couldn't believe it! I mean, the fan base for that show is just amazing. I've never experienced anything like it in my career. It's an interesting transition because multinational corporations have bought the movie studios and they're not in the business of making movies; their business is making money. They have a formula of what will make money. If Spiderman 150 will still make money, they'll make that.

"The film business as I knew it in the '70s and even into the '80s and early '90s, has dropped through the floor into the independent film movement. That's where 'cinema' is. Not the action-adventure films but films about people. But there's no money down there. Everybody who's working there is working for almost free. At least the actors are. I'm sure the producers aren't. What has happened in the meantime is that television has now become another place where real writers sell their work. There's really good writing going on in television, which is now becoming a much more—what should I say?—respectable art form in a way.

"The only thing is that their schedules are killer. They're really tight. Art takes time. You can't just whip art together. You can whip together a TV show; but, in order to do something really good, you have to have time. They're just beginning to have enough schedule to allow for good work. Let me tell you a story about House of Cards. You've seen it? Okay, you know the scene where I pull off my turban and say, 'I'm the mother. I'm the mother. I'm the mother.' As it was first written, it said I open my robe and pound on my bare torso saying, 'I'm the mother. I'm the mother.' I said, 'Gentleman, that is not going to happen. We will find another way.' I had a later scene where she finds out that I'm bald when she finds the wig. I said, 'Why don't you let me be bald, wear the turban, rip off the turban, and do that?' They said, 'Okay.'

"But then when we went to shoot, we discovered that it was four hours in the make-up chair to make me bald and they couldn't afford to do that for two days. So they said, 'We're going to have to do both scenes in the same day.' Which meant that I did about an 18-hour day. Which is not easy, even if I weren't 83 years old. So we did it. I got through it. Fine. Then they call me and tell me that they fired the camera man because the lighting was so bad they couldn't see me and they had to do the whole thing over. I did. I came back and did another 18-hour day."

"So the rage was real?" Cowan quipped.

Burstyn: "But, you see, if this were 10 years ago, they wouldn't have re-shot those scenes. They would just let it be whatever it was with whatever they could do in post-production. It's a step forward for television that they actually care enough about the quality to re-shoot a tough day like that."

At this juncture Noah Cowan opened it up to the audience for questions. I was first: "Ellen, it's so wonderful to have you here. It's such a delight. Thank you so much. Requiem For A Dream, to me, is one of the most harrowing performances I have ever seen; you were absolutely brilliant. Earlier you were talking about performance as depth, a depth performance, and in Requiem you take a dark descent. My question is: how do you back up from a performance like that? How do you move out of such darkness back into 'normal' life?"

"Do you know how I feel at the end of the day after doing a really harrowing performance like that?" Burstyn asked me. "Elated. I feel wonderful. Nothing feels better than doing a good job, whatever your job is. At the end of the day I just feel happy."

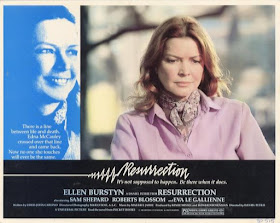

Cowan interjected that he could have asked a similar question about her performance as Edna in Resurrection (1980) because of the intense empathy of that role. He asked if it was hard to park a performance at the end of the day? To leave it on the set?

"No," she reiterated calmly. "I don't understand these stories from actors who say that they have to get away from the world. It just feels good. Resurrection is a film that I contributed a lot to; there's a lot of me in that film and what I was studying at the time. I think doing a job well is one of the most satisfying things anyone can do. I remember when I was preparing for Alice, I read Studs Terkel's Working where he interviewed people about their work. I found that they all took such pride in their work and that was where their flow was, when they could do a good job. I put that into Alice. I added that she really liked being a good waitress. Even though she wanted to be a singer and was waitressing as a day job, she felt good when she did a good job. I think that's very important in life and where we get the most satisfaction. I don't have any difficulty doing dark roles. I mean, at the time if it's an emotional role and heart-wrenching, I might make myself miserable. As I said to an actor at the Actors Studio the other day when she said, 'But it hurts', I said, 'Yeah, but that's the sacrifice we make for the people. That's what we do.' "

Q: You starred with the great Greek actress Melina Mercouri in A Dream of Passion (1978). What can you tell us about your relationship with her?

Burstyn: "Let me tell you a funny story about Melina. She was married to Jules Dassein. He was one of the great writers who was blacklisted. He went to Paris to live and his career from thereon was in Europe. He married Melina and wrote and directed A Dream of Passion. One day Melina comes to me and she says [Burstyn imitates her whiskey-throated voice], 'Do you like what I did there?' I said, 'Yeah, I think it's good.' She says, 'You don't think it's too much?' I said, 'No, Melina, I don't think it's too much.' She says [sobbing], 'Tell Jule!' I said, 'You tell him, Melina, he's your husband.' She said, 'He has this antagonism towards me.' "

Q: How do you convey to young actors that the work is going to take time? That they're going to have to be patient and that it's not all going to come overnight? What words of advice do you give to those young actors?

Burstyn: "I can tell you that when I studied with Lee, and I already had a career on stage, in film and on television. I started studying with him and doing the work that he taught, which is basically how to be real. The first time I worked with him, he said, 'You're very natural, darling, but you're not real.' Finally the day came when I was real, and not only in the Studio, but in my work. Being real is one thing when you do it for Lee in the Studio in a safe environment, but then when you try to bring that work to a picture that has to be shot quickly, it's not always possible. Or rather, it's possible but you don't always succeed. So I finally did it—I think it was The Last Picture Show, actually—and Lee saw it and he said, 'How long have you been studying with me now?' I said, 'Seven years.' He said, 'Yes, that's about what it usually takes.' It's not easy. Taking off the mask that you've been brought up to think is the right way to be—the nice, polite, acceptable, conventional way to be—and to be willing to peel that off and let show who you are underneath, that is hard."

A young woman admitted that she considered Burstyn to be one of her favorite actors and an extraordinary artist and that she is still mad to this day that Julia Roberts won the Oscar®. She wondered how Burstyn handled it?

"You know," Burstyn grinned, "I still have people who walk up to me on the street and go, 'You were robbed.' At first I didn't know what they were talking about. How do I handle it? I saw Julia Roberts on television the other night in an ad for a new movie she's playing and the thought that went through my mind was, 'You've got my second Oscar®!' "