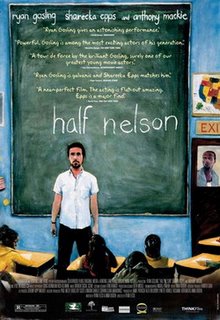

Half Nelson was one of my favorite press screenings from the 49th San Francisco International Film Festival, where I had the opportunity to speak with directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck. Half Nelson then went on to win the festival's FIPRESCI prize. It's easy to understand why. Half Nelson's compassionate portraits of Dan Dunn—a high school instructor caught in the grip of a crack habit—and Drey—the student who discovers Dunn's secret and is caught in the grip of latchkey impoverishment—provide an affirmative conviction that each can help the other. Ryan Gosling's performance as the addicted instructor is disturbingly believable and even more disturbingly sympathetic. Shareeka Epps as his streetwise young charge matches him scene for scene. Their unlikely friendship proves revelatory.

* * *

Michael Guillén: Congratulations on winning the IndieWIRE Critics Poll. That's some compensation for Sundance not recognizing what they had in their hands. But I was glad to hear you'd received some recognition because I think that you have a remarkable project here for a first feature, and of course you've done such a good turn for Ryan Gosling who—I predict—will get a nomination for an Independent Spirit Award at the very least, if not an Academy Award nomination. Your film title Half Nelson is a wrestling term, but my understanding is the title isn't that literal?

Ryan Fleck: It's a metaphoric use of the wrestling term. To represent someone who's struggling with all kinds of aspects of social political addiction, class, any kind of addiction.

Anna Boden: Yeah, it was inspired by the Miles Davis tune Half Nelson, which we imagine uses the metaphor in a similar way.

Ryan: I doubt that Miles Davis is writing songs about actual wrestling.

MG: That Miles Davis tune isn't on the soundtrack?

Ryan: A little expensive. [Laughs.] Not on our budget.

MG: Still, you got some good music through Broken Social Scene. I'm intrigued with the compassion the two of you have for each of your characters' situations. You show them at a juncture where they both fall into need and hopefully, potentially, help each other out of their respective situations. Where is that compassion coming from?

Ryan: I think it comes from the Bay Area and growing up here. I don't know. I'm kidding. Maybe I'm not kidding. I don't know. I just feel we really love these characters. It would be hard to make a movie about someone you didn't like. Even if Dan Dunn pushes the limits of what you will accept in a person, you ultimately root for this guy because he's such a great teacher and he's such a charming person. You really want him to get over whatever he's wrestling with and you want him to help Drey out and his students and you want her to get out of the situation that she's in. I think that's what it comes from. Liking the characters. Liking the people.

Anna: Even if all these characters in the film are judging themselves and judging each other, we don't feel like it's our jobs as writers or filmmakers to judge the characters.

MG: That's an appropriate but unexpected response. I've seen several movies about addicts and you usually get the gutter down-and-outer or Bukowski strata that, in my experience, doesn't hold true and doesn't align with the white collar addicts I know. They're certainly portraits that test compassion more than engender it. I'm not sure if you're aware, but here in San Francisco as in many parts of the nation there's a major methamphetamine epidemic. So many people I know, many of them friends, have been put into this half-nelson almost before they knew what was happening. At one point in the film when Dan is scoring from Frank [Anthony Mackie], there seems to be an indication that he was transitioning away from something like meth into crack. Is that a correct observation?

Ryan: Yes. I think he started out doing a lot of cocaine, which was more expensive, and I think occasionally he just wants something.

MG: That was a subtle point to get across. You zoom in on Dan when the shift to crack precipitates his downspin.

Ryan: I think it may have been something he may have done before but it's starting to increase in frequency.

MG: How did Ryan prepare for this role? Again, his depiction is probably one of the most accurate I've seen, especially after he would smoke the crack, and you would see him blanche and start to slightly sweat. How did he do that?

Anna: He went to meetings and he talked to people who had been through addiction. I don't know if he actually has ever smoked crack. You'd have to ask him. As an actor, he digs deep and is able to put himself into the position where he thinks his character should be in a way that most of us who aren't actors don't know how to do. So it's a little bit of a mystery to us how he's able to get into that place so realistically.

Ryan: But when he's there, he stays there. When we were shooting that scene in the bathroom, when he came from his dressing room—which was a classroom in the school—he came down, the set was totally quiet and everyone—it wasn't like I said, "Okay, everyone be quiet. Here comes Ryan. He's going to do some acting"—everyone just knew he was in a state where you just wanted to be quiet and watch. Between takes he wasn't like, "Hey guys! How did that go?" He was still in this weird place and really intense to watch.

MG: It's remarkable because it is the most accurate depiction of a crack fugue state that I've ever seen in a film. Returning to the compassion issue—because, really, you must be commended for what you did here—as I've been reviewing the critical response to Half Nelson—which is already amping up and it hasn't even opened yet—I'm finding some of the critics are judging. It's like they're not even evaluating the film; they're judging what's going on in the film. I thought that was sadly ironic that the compassion you're trying to get across in the film, not everybody's going to get it.

Ryan: Right.

MG: Dennis Harvey wrote in Variety that you have a challenge ahead of you in presenting this "unappetizing subject matter" to the average public. I felt, from something that I had read, that you two wanted to do the film out of a point of frustration and, clearly, so many people who fall into the clutches of addiction are frustrated with the fact that they can't make any change happen. The frustration leads to a loss of responsibility.

Ryan: Yeah.

MG: The scene I thought was incredible—among so many of them—was the denouement where Drey delivers drugs to Dan in his hotel room and realizes at that point what she's getting into and that she's harming people she cares about. Before then, she didn't seem aware of that. How did you two develop the script? Did you go through many drafts that you volleyed between each other?

Ryan: Yeah, it's evolved for a long time. One of the things about writing on spec before you have any kind of career in film, which we're still not sure we have….

MG: Oh, you have a career in film.

Ryan: Thank you. At the time we really wanted to tell the story but no one was saying, "Hey, what do you have? I want to take a look and maybe make a movie with you." We had time and we were trying to get things off the ground and we were making the short film version of it to try to raise awareness of the feature….

MG: That was Gowanus, Brooklyn?

Ryan: Gowanus, yeah. In that time we had plenty of time to keep talking about it and working out ideas and that scene particularly evolved over this time, going from exchange of dialogue to stripping it all out to where it's just where nobody says a word but everything is communicated.

Anna: When you have a job and someone pays you to write something, they give you three months, and you're getting paid so you have literally all those three months full-time to be working on it. That's great. That's a lot of time and we never had that where we could be working on writing full-time; but, we were working part-time over years and sitting with things. So even when we weren't writing, we were living this story and I think that was a great liberty to have.

MG: Do you think if you had been less compassionate with this character and you had painted him more stereotypically that things would have been easier for you?

Ryan: It's hard to say, I don't know.

Anna: We never thought about that.

Ryan: Well, there's definitely, like, okay so we've made this movie and the studios have seen it and they're scouting for directors and writers for their projects and we would go out there and we met a few people who might say, "I'm really taken, I really love the film. Is there…."—and they actually would ask us—"Is there a way you think it could be more commercial? Is there a way you could remake it somehow?" Which was completely bizarre to us because it was, like, well, no, this is the film that we wanted to make and we never considered the commercial viability of it. I don't know if that answers your question.

MG: I don't mean to belabor your compassionate treatment of these characters, it was just so stunning to me that I can't seem to let go of it. I suspect one of the main reasons you won the IndieWIRE poll among the critics was precisely because you've crafted a film where the audience is engaged to understand these characters rather than judge them. Usually in these kinds of films an audience is removed from addict protagonists; with Half Nelson, you're not. You feel for Drey, this young woman who has to be the adult among adults, and you feel for Dan, this teacher whose obvious disillusionment has led him to addiction. Some critics are saying, "Why didn't you show why he was having such a problem and why he became addicted?" Others are saying, "Oh, I'm so glad you had the scene with the parents with the end because then we finally got why he became addicted." There but for the grace of God…. Why do you think he became addicted?

Ryan: I think we touched upon that already. Some people oversimplify the end with the parents as—like you said—"Oh, now I get it. His parents were addicts." But I think what's going on there and why we wanted to diverge at the end of the film was to explore this idea of lost idealism, this idea that his parents came out of this activist culture of the '60s and felt that they could make a difference in some way. I think that they did and I think Dan Dunn thinks that his parents did, but, they've lost the ability to think that they can make change and not just in their communities and in the world, but in their own families even at some point. And when that happens, they go into denial and they start to use and abuse.

MG: How old are you guys?

Ryan: I'm 29.

Anna: I'm 26.

MG: My goodness. You're wise beyond your years.

Ryan: I don't mean to say that this is how the world works but I just thought it was a fascinating idea.

MG: This is how the world works; don't apologize. I'm a child of the '60s. I recently was talking with David Zeiger who directed the documentary Sir! No Sir! on Vietnam, this whole forgotten history. His documentary was so revitalizing for me because it allowed me to remember that spirit of my longhaired youth and I have to tell you it is the loss of that spirit that weakens you over time. It's the loss of that ability to make any kind of change that corrodes, where you're just working day after day after day, maybe you've even worked up to a pretty cush job, and it means nothing because you don't touch anyone, you're not doing anything of importance. As young filmmakers I'm anticipating that you're going to be touching people with your awareness of this spiritual crisis and its connection to chemical dependency.

Anna: Well, thank you.

Ryan: That's great. Thanks. We feel like—even though it's not totally resolved—that there's a glimpse of hope for the two of them.

MG: How did Ryan Gosling become involved?

Ryan: Serendipitously—I like to say that word—but we had imagined someone being a little bit older in that part, maybe mid-30s, more of a Mark Ruffalo type of guy, and through our casting director who was friends with Ryan's manager or agent or somebody, they just started talking about the role and his manager said, "Oh, that might be something that Ryan might be into." He got a hold of the script and—before we knew any of this had happened—we were having lunch with him to consider him for the role. We'd only seen The Believer, which we thought was a terrific performance, but thought this guy was just out of high school, how is he going to teach? We thought he was too young.

Anna: He'd aged.

Ryan: We looked at his other movies and I actually thought, "This would be great. He's still young but he's not 19. He could play late 20s and it will be great, this teacher who's idealistic right out of school. I feel that it worked. It shows his rapport with the students.

MG: Yes, he had to have that street cred with them. And Shareeka. What a natural. How did you come across Shareeka?

Anna: When we were casting for the short a couple of years ago we didn't have a casting director so we literally walked into—well, we called ahead of time—but we walked into public schools in Brooklyn and Manhattan and told the kids about open auditions and she came. She'd never acted before but she was charming and great and natural and we ended up casting her in the short. We're really lucky to be able to keep her for the feature because she didn't grow too much even though it'd been a couple of years, even though it was the difference between 13 and 15.

MG: Is she still acting?

Anna: She wants to pursue it now. She got a manager after Sundance this year.

MG: As a young actor, as a young person, how did she deal with these issues that she was seeing in the movie or having to enact in the movie?

Ryan: I think there are a lot of parallels in her own life, which we weren't really aware of, but became clear, we could just tell there was a lot going on with this kid's life, and instead of hiding from it, she was able to embrace it and use it for her performance.

MG: My final question: you've dealt a lot with dialectics. Can you touch upon why the use of dialectics? You feel it expresses how change occurs?

Ryan: Yeah, for all of the political, subversive stuff involved with it, I thought that that fit this rebellious teacher, what he wanted to explore in the classroom.

Anna: And in his own life because he's struggling with how to make change in his own life as well so he uses this as a tool for himself as well as his class.

Ryan: And the idea [that] all of these characters are made of their opposing force. Frank is not 100% bad. He's a good friend in some ways. And the same with Dan. He's a good teacher but he's also got this secret other life going on. And Drey is being pulled between them. I just felt that metaphorically it was provocative.

MG: You've toured the festival circuit primarily in North America?

Ryan: So far, yeah.

MG: Any invitations to go overseas at all?

Ryan: Not yet. We're working on it. Think Film is just trying to figure out….

Anna: Strategize….

MG: Congratulations, by the way, on them picking you up. I'm interested in the phenomenon of new directors and their first year on the festival circuit; how they cope with becoming festival darlings. What's that like for you?

Ryan: It's been great. We're level-headed about it.

MG: You've worked hard for it.

Ryan: It's nice to have people respond to the film.

MG: You have a screening tonight?

Ryan: Tomorrow night.

MG: And you'll be there for Q&A?

Ryan: Yeah.

MG: I'll try to drop in to see how the audience reacts.

Ryan: It will be good because it won't all be filled with my dad's friends. [Laughs.]

MG: Thanks again.

Photo of the directors courtesy of Henny Garfunkel/Retna Ltd., Filmmaker Magazine, where Matthew Ross likewise interviews Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck.

Cross-posted on Twitch.