Jacob Gentry's Synchronicity (2015) had its world premiere at last summer's Fantasia International Film Festival where my review for The Evening Class stated: "With its stylish evocation of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982), homage becomes—for genre fans, at least—a form of time travel. However, Synchronicity is less a replicant than its own atmospheric application of noir aesthetics to a sci-fi narrative about time looping through parallel universes. Although we've seen this premise before with such films as Timecrimes (2007), Looper (2012) and Time Lapse (2014)—and the requisite effort to bring compromised timelines back into alignment—Synchronicity admirably maximizes the bang for its buck and delivers an elegantly-mounted puzzler with swank art direction by Jenn Moye that looks like it was created with a considerably heftier budget, bolstered by Ben Lovett's melancholic score that recalls Vangelis without losing its own significant character."

My conversation with Gentry and his lead actor Chad McKnight followed shortly thereafter. Synchronicity is now poised to rollout on multiple platforms. Theatrically, it opens today at the Sundance Sunset Cinema in West Hollywood, California; the Plaza Theatre in Atlanta, Georgia; the Lake Worth Playhouse in Lake Worth, Florida; the Jean Cocteau Theatre in Santa Fe, New Mexico; and the Gateway Film Center 8 in Columbus, Ohio. This compelling mindbender is also available on demand at numerous streaming sites, including Amazon, iTunes, VUDU and YouTube, among others.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

BERLIN & BEYOND (2016)—B&B IN B&W

More by chance, I presume, than design, several entries in the 20th edition of San Francisco's Berlin & Beyond Film Festival (January 14-20, 2016) were shot in B&W and projected large on the Castro Theater's historic screen. Brendan Uffelmann's impressive cinematography, in fact, along with Paul Wollin's physically commanding breakout performance, recommended the U.S. premiere of Martin Hawie's Toro (2015).

German Film Quarterly's nutshell synopsis: "Toro, whose real name is Piotr, came to Germany 10 years ago, where he works as an escort, hoping to save money to return to Poland with his best friend Victor. But Victor has sold his dreams for drugs. When three small-time criminals are out to get him, Toro's and Victor's hostile environment loses its balance and their longstanding friendship is put to the test."

"Friendship" as the working euphemism in this instance does little to guise the film's reveal that Toro is gay. Within the first few scenes of the film Wollin drops his pants to flash his glutes. If your gaydar doesn't kick into high gear, then you need a check-up. What troubles this script is a lack of back story that would make Toro's devotion to his drug-addled boyfriend Victor (Miguel Dagger) believable. Without knowing who Victor might have meant to him in earlier years, and what the nature of their relationship is really about, Toro comes off as stupidly throwing pearls before swine. Other characters are introduced incidentally as well, making for uneven storytelling. This film aspires to a certain height but is held back by a queer grip that settles for softcore porn before character development. Skin takes over the script. What did I really learn about Toro from his prolonged practice "moves" on his mattress?

You tell me.

With equally assured purpose, the North American Premiere of Burhan Qurbani's We Are Young. We Are Strong (Wir Sind Jung. Wir Sind Stark, 2014) deploys Yoshi Heimrath's B&W cinematography in its first half, then self-consciously shifts to color midway through the film with no apparent reason other than, perhaps, fire looks better in color? Or to demarcate the moment when Germany's 1992 Rostock riots threatened a community of immigrant Vietnamese? That stylism might draw unnecessary attention to itself, but credit is due Qurbani for creating a sense of the rising anger of disaffected German youth shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Jonas Nay's performance as Stefan reveals an unsettled mind easily persuaded towards xenophobic neo-Nazism.

The recipient of B&B's Spotlight Award, Tom Schilling, attended the festival to introduce the revival screening of Germany's festival and box office hit Jan Ole Gerster's A Coffee in Berlin (Oh Boy, 2012), handsomely shot in B&W by Philipp Kirsamer. Schilling garnered considerable acclaim—including a German Film Award for Best Actor—for his feckless performance as Niko Fischer. At Variety, Peter Debruge wrote: "Gerster's decision to film in black-and-white lends a melancholy romance to Niko's various encounters, infusing even a scene where he's seen flushing leftover meatballs down the toilet with a measure of introspection."

Also screening at B&B, though not in B&W, was Schilling's follow-up performance in Baran bo Odar's own follow-up four years after The Silence (2010)—his thoughtful yet disturbing study of the relationship between two child molesters. Odar returned with an altogether different vehicle Who Am I: No System Is Safe (Who Am I: Kein System ist sicher, 2014), a slick surface glamorization of cyberhackers revved up with hypermasculine highjinks. Schilling plays Benjamin, a young German computer whiz who applies his skills to help a subversive hacker group be noticed on the world's stage.

Perhaps most intriguing about Who Am I is its staged enactment of online interactions in darknet. Avatars suspensefully encounter each other in the personified space of a crowded subway train. It's an attractive visual calesthenic that underscores Who Am I's kinetic style. Hoodies and Anonymous masks become the new black.

For Mara Eibl-Eibesfeldt's The Spiderwebhouse (Im Spinnenwebhaus, 2015), boasting its U.S. premiere at B&B, the B&W camerawork of Jürgen Jürges provided a framing intimacy to this children-in-peril narrative. While Mother battles her demons up at the Sunvalley Psychiatric Clinic, her children are left unsupervised and—as everyone knows—childhood cannot wait for the parent to grow up. The eldest boy Jonas (Ben Litwinschuh) becomes what Mark Cousins terms "the child-parent" raising his younger siblings and standing in for a mother who's gone missing and a father who has abandoned them.

B&B's closing night film—the U.S. debut of the restored version of Walther Ruttmann's Berlin, Symphony Of A Great City (Berlin, Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt, 1927)—featured an array of B&W cinematographers—Robert Baberske, Reimar Kuntze, László Schäffer, and Karl Freund—visually weaving a vibrant urban tapestry, accompanied by the rock rhythms of ALP (Aggressive Loop Productions and/or Analog Love Providers), a trio of musicians who unfortunately defused their energized performance in a deflated, and unnecessary, Q&A.

German Film Quarterly's nutshell synopsis: "Toro, whose real name is Piotr, came to Germany 10 years ago, where he works as an escort, hoping to save money to return to Poland with his best friend Victor. But Victor has sold his dreams for drugs. When three small-time criminals are out to get him, Toro's and Victor's hostile environment loses its balance and their longstanding friendship is put to the test."

"Friendship" as the working euphemism in this instance does little to guise the film's reveal that Toro is gay. Within the first few scenes of the film Wollin drops his pants to flash his glutes. If your gaydar doesn't kick into high gear, then you need a check-up. What troubles this script is a lack of back story that would make Toro's devotion to his drug-addled boyfriend Victor (Miguel Dagger) believable. Without knowing who Victor might have meant to him in earlier years, and what the nature of their relationship is really about, Toro comes off as stupidly throwing pearls before swine. Other characters are introduced incidentally as well, making for uneven storytelling. This film aspires to a certain height but is held back by a queer grip that settles for softcore porn before character development. Skin takes over the script. What did I really learn about Toro from his prolonged practice "moves" on his mattress?

You tell me.

With equally assured purpose, the North American Premiere of Burhan Qurbani's We Are Young. We Are Strong (Wir Sind Jung. Wir Sind Stark, 2014) deploys Yoshi Heimrath's B&W cinematography in its first half, then self-consciously shifts to color midway through the film with no apparent reason other than, perhaps, fire looks better in color? Or to demarcate the moment when Germany's 1992 Rostock riots threatened a community of immigrant Vietnamese? That stylism might draw unnecessary attention to itself, but credit is due Qurbani for creating a sense of the rising anger of disaffected German youth shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Jonas Nay's performance as Stefan reveals an unsettled mind easily persuaded towards xenophobic neo-Nazism.

The recipient of B&B's Spotlight Award, Tom Schilling, attended the festival to introduce the revival screening of Germany's festival and box office hit Jan Ole Gerster's A Coffee in Berlin (Oh Boy, 2012), handsomely shot in B&W by Philipp Kirsamer. Schilling garnered considerable acclaim—including a German Film Award for Best Actor—for his feckless performance as Niko Fischer. At Variety, Peter Debruge wrote: "Gerster's decision to film in black-and-white lends a melancholy romance to Niko's various encounters, infusing even a scene where he's seen flushing leftover meatballs down the toilet with a measure of introspection."

Also screening at B&B, though not in B&W, was Schilling's follow-up performance in Baran bo Odar's own follow-up four years after The Silence (2010)—his thoughtful yet disturbing study of the relationship between two child molesters. Odar returned with an altogether different vehicle Who Am I: No System Is Safe (Who Am I: Kein System ist sicher, 2014), a slick surface glamorization of cyberhackers revved up with hypermasculine highjinks. Schilling plays Benjamin, a young German computer whiz who applies his skills to help a subversive hacker group be noticed on the world's stage.

Perhaps most intriguing about Who Am I is its staged enactment of online interactions in darknet. Avatars suspensefully encounter each other in the personified space of a crowded subway train. It's an attractive visual calesthenic that underscores Who Am I's kinetic style. Hoodies and Anonymous masks become the new black.

For Mara Eibl-Eibesfeldt's The Spiderwebhouse (Im Spinnenwebhaus, 2015), boasting its U.S. premiere at B&B, the B&W camerawork of Jürgen Jürges provided a framing intimacy to this children-in-peril narrative. While Mother battles her demons up at the Sunvalley Psychiatric Clinic, her children are left unsupervised and—as everyone knows—childhood cannot wait for the parent to grow up. The eldest boy Jonas (Ben Litwinschuh) becomes what Mark Cousins terms "the child-parent" raising his younger siblings and standing in for a mother who's gone missing and a father who has abandoned them.

B&B's closing night film—the U.S. debut of the restored version of Walther Ruttmann's Berlin, Symphony Of A Great City (Berlin, Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt, 1927)—featured an array of B&W cinematographers—Robert Baberske, Reimar Kuntze, László Schäffer, and Karl Freund—visually weaving a vibrant urban tapestry, accompanied by the rock rhythms of ALP (Aggressive Loop Productions and/or Analog Love Providers), a trio of musicians who unfortunately defused their energized performance in a deflated, and unnecessary, Q&A.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

BOOK EXCERPT—GIRLS WILL BE BOYS: Crossed-Dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934

|

| Cover image is Marie Eline, the Thanhouser Kid |

Her anthology, Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space (Indiana University Press, 2014), co-edited with Jennifer Bean and Anupama Kapse, won the Society of Cinema and Media Studies’ Award for Best Edited Collection of 2014.

Her new book, Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934, will be published by Rutgers University Press in February 2016. As noted by Publishers Weekly: "Horak (co-editor, Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space) has produced a meticulously researched, astutely argued, and highly readable text on cross-dressing and lesbianism in early American cinema. The book first examines female cross-dressing in American films between 1908 and 1921. Horak describes how women playing male roles, often young boy characters such as Peter Pan and Little Lord Fauntleroy, were initially labeled 'innocent' and 'pure.' She argues that the trend of young women cross-dressing as cowboys in 'Frontier Films' and as boys in chase films portrayed an active frontier girlhood as a 'revitalizing' but necessarily transitory phase in women’s lives. On the other hand, in stories set during the Gold Rush, cross-dressed women 'legitimized men's same-sex desire in these sex-imbalanced places.' The book's second part explores depictions of lesbianism in mainstream American culture and cinema between 1921 and 1934, as well as female stars such as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich who wore masculine clothing. Horak concludes with the more censorious climate of the 1930s, clearly illustrating how a once-accepted practice came to signify taboo sexuality. Her use of archival materials is impeccable and her filmic and historical analyses clearly display a nuanced understanding of her topic."

More of a teaser than an excerpt (I was only allowed 450 words), I am nonetheless indebted to Rutgers University Press for permission to publish the following paragraphs from Horak's introduction to her upcoming publication. The entirety of the introduction to her volume can be accessed through a Google Books search, whereas her original research—satisfying her UC Berkeley dissertation—can likewise be secured online. While at Berkeley, she programmed an eponymous film series at the Pacific Film Archive. She has likewise published various articles pertaining to her ongoing research at various venues, including "Afterthoughts and Postscripts, 52.4" for the Society for Cinema & Media Studies (focusing on "The Female Boy on the Frontier: The Strange Case of Billy and His Pal (1911)"; "Edna 'Billy' Foster, the Biograph Boy" in Not So Silent: Women in Cinema Before Sound (eds. Sofia Bull and Astrid Söderbergh Widding); "Landscape, Vitality, and Desire: Cross-Dressed Frontier Girls in Transitional-Era American Cinema", for Cinema Journal (Volume 52, Number 4, Summer 2013); and " 'Would you like to sin with Elinor Glyn?' Film as a Vehicle of Sensual Education" for Camera Obscura (Volume 25, Number 2 74: 75-117, 2010). She also contributed to R.A. McBride and Julie Lindow's Left in the Dark: Portraits of San Francisco Movie Palaces. Jan-Christopher Horak profiled Horak for his "Feminist Study of Early Cinema."

* * *

In the first part of this book I will show that the American moving picture industry used cross-dressed women in the 1910s to help the medium become respectable and appeal to audiences of all classes. Cross-dressed actresses embodied turn-of-the-century American ideals of both boyhood and girlhood. The second part of the book traces the emergence of lesbian representability in American popular culture between the 1890s and 1930s. Only in the late 1920s, in the wake of the multi-year censorship battles over the play The Captive, did codes for recognizing lesbians begin to circulate among the general public—codes that included, but were not limited to, male clothing. This development tarnished cross-dressed women's wholesomeness and inspired the first efforts to regulate cinema's cross-dressed women. It also established the transgressive meanings with which we are familiar today. This book ends where other accounts of cross-dressed women and lesbians in American cinema begin—with Dietrich, Garbo, and Hepburn.

Previous scholars have read representations of cross-dressed women as mirrors of their own concerns and identities. That is, feminist scholars have read cross-dressed women as feminists; lesbian scholars have read them as lesbians; and queer and postmodern scholars have read them as queer and postmodern. Transgender scholars have considered cross-dressed individuals as examples of historical gender variance, though they usually stop short of claiming them as trans. Indeed, the open meanings of cross-dressed women are a key part of their appeal . But scholars' interpretive zeal has obscured the ways that representations of cross-dressed women were understood at the time they were made and circulated. Reading cross-dressed women as embodiments of contemporary concerns flattens and sometimes misrepresents the cultural work that they were doing in their own times. While my interest in historical representations of cross-dressed women is inspired by my present-day experiences of gender and sexuality, in this project I have tried to stay open to what they meant in their own contexts. One of the surprising things I've discovered was that cross-dressed women were not inherently subversive were sometimes mobilized in support of nationalist, white supremacist ideologies. Rather than making abstract identitarian claims for these figures, this book explores the multiple, contradictory meanings attached to them, how these interpretations developed, and why they changed. [Footnotes omitted] ("Introduction", p. 2)

Thursday, January 14, 2016

PSIFF 2016—TALKING PICTURES: OSCARS® BUZZ

|

| Courtesy of The Hollywood Reporter |

|

| Courtesy of The Hollywood Reporter |

Feinberg welcomed his audience and gave thanks to PSIFF Artistic Director Helen du Toit and her programming team for making the panel possible. He equally thanked the panelists for making films that were such a pleasure to watch this year. He promised that by the time we were through with the panel discussion, we would want to seek these films out, an opportunity unique to PSIFF: nowhere else would all nine films on the Oscar® shortlist be available for viewing.

* * *

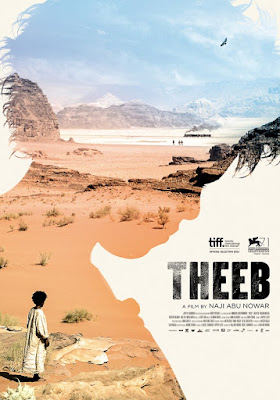

Scott Feinberg: On behalf of Colombia's Embrace of the Serpent—a film about the last surviving member of an Amazonian tribe and the people who come to see him in 1909 and 1940—please welcome, Ciro Guerra. On behalf of France's Mustang—a film about five orphaned sisters who come of age in their grandmother's deeply-conservative household in Turkey—please welcome, Deniz Gamze Ergüven. On behalf of Hungary's Son of Saul—a film about a Jew in a Nazi concentration camp who comes across a body that may be his son and risks his own life to give the boy a proper burial—please welcome László Nemes. On behalf of Jordan's Theeb—a film about a Bedouin child forced to grow up very quickly when people he has accompanied on a trip through the desert are ambushed—please welcome Naji Abu Nowar. And last, but not least, on behalf of Denmark's A War—a film about a Danish military commander who makes a fateful decision when his company of troops in Afghanistan are ambushed—please welcome, Tobias Lindholm. Thank you all for being here.

To begin with, I want to talk about what inspired each of you to tell the stories that you've told in these films and what it was like getting it off the ground because I know—from having read up on you guys—that in many, if not all, cases it was a challenge, as I think it probably always is; but, in some very interesting ways in this case.

Ciro, you've lived—as I understand it—in Colombia your whole life but like a lot of Colombians had not really experienced the Amazon. For many years it wasn't a safe place to go; but, that's changed a little bit, I guess, in recent years. Was that what made you decide to go explore it in film?

Ciro Guerra: Yes, the Amazon is half of our country. I had done two previous films, which were very personal and which dealt with issues of family, culture and personal feelings. I wanted to get away from all that and to take a journey into the unknown and to invite the viewer into the unknown.

Feinberg: Deniz, you were born in Turkey. Was the story that you tell in Mustang at all similar to your experience? What made you decide to go back to Turkey in your film to tell this story?

Deniz Gamze Ergüven: My life takes me back and forth between France and Turkey, and it's exactly that zooming in and out of Turkey that made me want to tackle the issues in Mustang of something specific in the experience of being a girl, a woman, in Turkey, which is a permanent sexualization of every movement, every action, and every parcel of skin of girls, which starts—as with the characters in the film—at a very early age. Just like the characters in the film, I sat on the shoulders of boys when I was 12 or 13, which I was told was totally disgusting and questionable. It's a precise filter that articulates the place of women in society, so I wanted to discuss this question.

Feinberg: László, this is also your feature directorial debut and I understand that the idea came to you while you were working as an assistant to another very interesting filmmaker: Béla Tarr. What motivated you to revisit the experience of someone in a concentration camp?

László Nemes: I read these texts by the members of the Sonderkommando workers of the crematorium in Auschwitz. These are not very well-known texts. They exposed me to a reality unknown to me: the reality of the extermination. As a reader, you were projected into the middle of it and I wanted to find a cinematic way to express the vision from the inside: how to convey something that has never been conveyed. What has been forgotten in the so-called holocaust film genre is the individual, the person, and I wanted to concentrate on the individual.

Feinberg: Naji, can you talk about the present-day applicability of the story that you tell about, basically, an outsider, a Westerner, coming into a community in that part of the world and throwing things, essentially, into disarray? Was there a larger point that you were going for? A metaphor for the present day?

Naji Abu Nowar: The Arab Spring hadn't happened yet, but I think it was in the zeitgeist of the time, certainly not just on a great level, but in terms of the fact that I have been trying to make films for ten years. We'd struggle and always get rejected. There came a point when we were developing Theeb where we said, "We no longer need permission from someone. We're just going to do it." That was liberating. Me and my colleagues haven't looked back since that moment once we realized that we should just do it. But I'm not going to say that I predicted the Arab Spring, because I didn't, but I think it was in the air.

Feinberg: Tobias, as I understand it you've not been a soldier yourself, but—obviously, with many people in your country as with many people in this country—you felt the impact of the last 15 years of war. In Denmark, that's been very much the case with incidents including the one that you documented. What is it that made you decide to make this particular real event the focus of your film?

Tobias Lindholm: It's the first war that Denmark has fought since the Second World War. In the Second World War we fought for five hours against the Germans and then gave up. So it's a new thing. This war has defined my generation more than anything else. We became that war-faring generation. There's a new Denmark growing that I'm a little scared of. I thought it was appropriate to tell a story about it. It's not one real event that the film is based on; it's several cases. I've taken bits and pieces from the reality and the logic of those cases and tried to put it in a story seen from a soldier's perspective of how complex the job that we ask these guys to do actually is. What happened in Denmark is that the politicians that made the decision to go into these wars, afterwards started to prosecute the soldiers 1) because they needed to try the rules of engagement under the Danish law system—that makes sense—but also 2) to try to legitimize their own actions and decisions by pushing them away and blaming the young soldiers for what happened down there instead of looking at themselves.

Feinberg: I want to ask each of you about some of the casting challenges and interesting decisions that you made. One point I want to make is that in a number of these films there are terrific child actor performances. Let's talk about those.

Ciro, I want to ask you about the very memorable sequence in your film in the Amazon at a mission where children are being indoctrinated into Christianity. A number of kids—who, I believe, are from that part of the area—are being abused at this mission. Where did you find these guys and how—even just in terms of language—were you able to direct them?

Ciro Guerra: During the process of research I found out that with the indigenous people of the region the coming of Christianity was a big scar. Christianity arrived in a brutal way. Basically, children would be taken away from their families. Some of them would be sole survivors of families that were wiped out during the rubber exploitation. They were confined to these missions where they were forbidden to speak their own language. They were forbidden to think in any way like indigenous people of the Amazon should. Jesuit priests would be really hard on them. It's a part of the story that hasn't been told. It's become a taboo subject. After seeing the film, many indigenous people have approached me and said, "Thank you for showing this because it has been something that happened over 30 years ago and no one ever speaks about it. No one knows about it." For me it was very shocking.

In order to have children participate in these kinds of sequences, you don't need to put them into this state. You do the opposite. Basically, you work with them as if it's a game. You say, "This is a game and someone is beating you and you're really in pain." Kids have so much imagination and they're willing to try everything. When you take a game to a serious level, they go all the way. I ran tests with the children. They did some scenes that were really harrowing and they would cry, I would say, "Cut!", and they would immediately start joking around and say, "Let's do it again!" It's a game for them but it's also a game for us. I like to keep the drama on the screen and, afterwards, it was a lot of fun for us.

Feinberg: Deniz, there are five young women in your film, ranging—at least at the time—from 13 to 20. An amazing thing I learned after watching your film was that four of them had never acted before! How did you assemble this group who are so good together and so good as actresses that you would never imagine they had never acted before?

Deniz Gamze Ergüven: We looked at a long list to choose these girls. I had asked these young actors to do specific things to let me know if I could direct them. I never said, "This girl is a good actor. This girl is not a good actor." I wanted great listening and great imagination. They had to be one body. They had to look like a pile of puppies and be playful.

Feinberg: Naji, your whole movie centers on one child actor, Jacir Eid Al-Hwietat, and he's terrific. You needed him to be truly Bedouin to play that part. My understanding is that it was a happy accident that you found Jacir in the first place, as you were just beginning the process?

Naji Abu Nowar: We worked for a year developing the script with the Bedouins and did eight months of acting workshops. It was just luck that we found Jacir. We didn't have any money so we did a trailer to try to convince investors to fund us and I asked our Bedouin producer to find us a 9 to 12-year-old boy. He sent his son. He was the first person I'd lived with so I was actually upset because I knew Jacir and knew that he was very shy. He'd always be in the corner. He'd never talk. I thought, "Oh my god, I'm in serious trouble now."

It was that magical thing: we put him on camera, had him moving and doing things, and he just lit up the screen. We never looked at anyone else. Although we had spent a lot of time developing the other actors, with Jacir it was really more about just keeping him comfortable and helping him get over the social taboos. In Bedouin culture, a young boy should be seen and not heard and he certainly shouldn't be kicking people and such things, as seen in the film. That was the big challenge: getting him to overcome the social taboos of things he shouldn't be doing as a Bedouin boy.

Feinberg: Tobias, in your film we see two textures—more than that—but two main settings: at conflict in Afghanistan, and then back home. Back home you have several kids as well in your film. Do these processes sound familiar to you?

Tobias Lindholm: The best way to make the kids work was pretty much to just let them be kids, so we didn't write any lines for them. I would invite them into the home for the family and fill it with what they liked—toys, film stuff—and they would just run around. Tuva Novotny, the actress who played the mother, would help me control the situation, because basically that's what parenting is with children of that age: trying to control the situation. I needed them to do as much chaos as possible so they just went around, didn't follow a script at all, and she would try once in a while to get them into the narration. Basically, I just needed them to put life in there.

There's one incident in the film where the youngest kid cries in the hospital. He eats some pills and she has to take him to the hospital. He cries for real. The thing is he always cried every morning for 30 seconds when his father left. So that day I asked the father to stay until the final moment when we were ready to shoot. I had 30 seconds of him crying. We got those real tears and the great thing was that he made up his own line; he says, "Where is my Papa?" As you know watching the film, he's in Afghanistan, so it all makes sense. But that was him calling for his real dad.

Feinberg: Moving on to casting decisions that are not necessarily about children, László, I wanted to ask you about Géza Röhrig who is someone, I believe, you had known for a while? Correct me if I'm wrong, but he's a Hassidic Jew, a poet, and had been a punk rock musician at one time?

László Nemes: He's not Hassidic.

Feinberg: But he's an interesting, colorful guy. How did you two guys meet and what made you think that this person—who had never acted in a feature film before—could carry your whole movie?

László Nemes: In a way Géza embodies the scars of the 20th century. He carries the suffering of the 20th century, and Eastern Europe. The destruction of the European Jewish civilization is in him. He has been thinking about this his entire life. His entire life has been in preparation for this film, which might seem like a crazy idea but is true to a certain extent.

He had a strange life in the '90s. He was supposed to be a film director, enrolled in the program, and then quit before making his first film, was in acting, then a punk musician, and then left for New York. What I really wanted was someone who was ordinary and extraordinary at the same time. My main character was / is an ordinary man, not a hero; we're not talking about a hero who turns insane, if you will. That's the process that's inside him already. I knew it was risky to pick someone who hasn't been in front of the camera in 20 years and who had forgotten about filmmaking in a way, especially for this kind of film because the whole film is based on him. If he was bad, the whole film would be bad. There's no way to come out from this. But, actually, I think that gave us the energy and the willingness to work together.

Feinberg: Ciro, why was it important to shoot Embrace of the Serpent in black and white?

Ciro Guerra: There were so many reasons. I could speak for two hours about why it was important to shoot the film in black and white. It was such a huge decision. The first inspiration for the film were the images taken by the explorers. Those images were unbelievable when I saw them. They were daguerreotype photographic plates. When you saw them, you saw an Amazon that was completely different than the Amazon that you think about. It was completely devoid of exuberance and exoticism. It was a different world and time; but, looking at it through those images, I started thinking this film should be in black and white. When I went to the Amazon I realized that it would not be possible for any kind of film, any kind of video, any kind of representation to give you a real idea of what the green of the Amazon is. Amazonian people have 50 words for what we call green. I thought, maybe by taking it away it would be possible to trigger the imagination. It's not the real Amazon you see in the film—it's an imagined Amazon—but, what we imagine would certainly be more real than what I could portray. Also, when I talked to the Amazonian people, I realized that with black and white images there was no difference between nature being green and us being something else. Every human, every bird, every drop of water is made up the same in black and white so it was perfectly coherent. I decided the film had to be in black and white and we had to overcome the expectations of a lot of people, but we stuck to it, and—if I had been forced to film in color—I would have preferred not to do it.

Feinberg: László, why do you leave it uncertain whether or not the boy is, in fact, Saul's son?

László Nemes: I believe films should leave room for the imagination of the viewer. There's been a tendency in cinema to get rid of the viewer, to kill the imagination, to show everything, to tell everything. I grew up with films that made me feel the magic of cinema because I was involved with them. They left room for my mind. I wanted to have a story and a visual experience that takes place in the mind of the viewer more than on the screen. It had to be a narrow approach to allow an opening in the mind. For me, cinema is this approach. I wanted the film to become a journey for the audience. It had to be a journey because—especially in this context of the concentration camp—you have no access to all information; you have no access to the entire story. As an individual, you only have access to your own experience, which is limited. As we follow the story with the main character, there are questions asked to the audience; the main question being: when there's no more hope, no more God, and no more religion, is there still room for an inner voice that would allow the individual to remain human? I'm not forcing the audience to answer in one way or the other. I want this to be a personal journey with a personal answer.

Feinberg: Naji, what was it like to shoot this film in the desert—as you guys actually did—and, in fact, in the same desert as where Lawrence of Arabia was shot 50+ odd years earlier? How did those logistics work?

Naji Abu Nowar: It's tough. We shot in two deserts. The first desert is actually the border between Israel and Jordan, called Wadi Rum and that's a military zone, so we had to get permission from the Jordanian military to shoot there. The scary thing about it is that no civilians go there so it's full of all the creepy crawlies you can imagine. The sound man found a snake in his bag. It meant that all our equipment was light. There was no cell phone reception. There were flash floods, sand storms, and all that kind of stuff. It got pretty dangerous at times; but, the one thing we had was the Bedouins. I'd known from living there that you always have to listen to the Bedouins. I nearly got myself killed once by getting lost. I thought I was like them and went off on my own. They tracked me, found me and saved me. We always listened to them. So when they said that there was going to be a flash flood in five minutes, we packed up the set and evacuated.

Feinberg: One thing I want to ask all of you to talk about is the process—which can be a marathon—of getting your film out to be seen by a lot of people around the world in the festival circuit, which we're on right now, and all of that. If you could just share for you where it began and what it has been like? In a number of cases I think it was a film festival that catapulted your movies into the "must watch" list for a lot of people. Film festivals have the ability to bring out the best of what's out there. To begin with, we had three of these films unveil at Cannes: Mustang, Son of Saul and Embrace of the Serpent. Deniz, what was that like to have your film unveil at Cannes, which in itself is a sort of circus, right?

Deniz Gamze Ergüven: In the beginning when you're starting to work on a film it's like you're on top of a mountain. You're pushing this huge rock on your own for a long time and it doesn't move an inch, not even a vibration. There's a few points, at the eve of a shoot, when you literally can't do anything. Then it just takes off. Once the film is out of post-production, it's as if you're taking your kid to kindergarten for the first time. You see the film have its own life. We screened in Cannes and then the film started having its own life, literally. It's thrown into orbit. But you still stay, holding onto your kid.

Feinberg: Out of Venice we had A War and Theeb. Tobias, what was it like to start your journey on the Lido?

Tobias Lindholm: It was a great experience. I did a film called A Hijacking that premiered there as well so I was pleased to come back. My wife's Italian so it was great to get her back to her mother there. It's a strange feeling because it's part of the job, but it's not a part of the job that I enjoy too much. I like to work. I love to sit and write. I tend to believe that's where the big battles are won. Then, at a point, you start to hope that it can become a film. Then, when you start to make that film, you hope that it can become a good film. And then you hope for an audience. And then you hope for a festival where you can actually meet an international audience.

When we started doing A War, for me it was important to be honest to the real soldiers who were acting in the film. It felt strange to forget that because that felt so important when we started the film and now suddenly it was important how reviewers or how a festival accepts your film or not. I always feel a little conflicted in that. It's great, it's wonderful, but at the same time it's far away from the working space that I enjoy so much being in. So in many ways it's leisure time because you can drink rosé and meet people; but, at the same time, it's scary and I've probably never been as distant from my films as I feel at festivals.

Feinberg: I do want to expand this point for a second, Ciro, to find out if and how the folks in the Amazon have been able to see your film?

Ciro Guerra: Yes, the first ones to see it were, of course, the actors. Nilbio Torres, who played the young Karamakate, had never even seen a film before. After the film, I asked him, "What was it for you?" He said it was scary. We brought him to Bogotá to do the final sound work and we showed him an unfinished version of the film and he said, "I was in Bogotá, it was a city, very strange to me, but then the lights went out and, suddenly, I was in the jungle again. Everything felt real." When he saw the jaguar in the film, he had never seen a jaguar up close. He had actually hunted them but to see a jaguar up close was an experience for him. As for the hallucinatory sequence, he said he almost fainted because he was so scared.

But they loved it. They said, "This is what we were doing. This is unbelievable." After the film premiered in Venice, we managed to screen the film for the people in the Amazon. We screened it three times in different places. It was a big deal for the people there. Some of them walked for three days to see the film because they came from so far away. We managed to turn a maloca, an Amazonian longhouse, into a cinema for one night. It was magical.

For them it was a big deal to see their language on screen. There are some words of the Ocaina language in the film. The Ocaina language will disappear in this generation. It is spoken by only 16 people, so it was a big deal for them. To see foreign actors speaking their language was powerful. When they saw the mountains at the end of the film, which are a very big part of their mythology, it was like a football game: everyone was screaming and clapping. That was one of the most emotional screenings I've ever attended.

Feinberg: Naji, back in Jordan has there been any way for the Bedouins to see their story be told?

Naji Abu Nowar: Yeah. The main actors, Jacir and Hussein Salameh Al-Sweilhiyeen, we got them passports. It was the first time they were on a plane and they attended the premiere in Venice. Very similar to what Ciro was saying, they went to a 1,500-seat cinema and it was the first time they had been in a cinema and the first time they had seen a film. It was an amazing experience for them, including a standing ovation from the crowd. It was incredible. I had never seen these guys show real emotion, but they were crying. For the Jordanian premiere, we went to Wadi Rum in the village where we lived, pulled all the surrounding tribes, and screened the film under the stars. They loved it. We did have one problem. The niece of Hussein couldn't grasp the concept of cinema and she thought he had really died. She was absolutely inconsolable and we had to take him out of the premiere and bring him around as proof of life that he still existed.

Feinberg: Deniz, would you feel comfortable showing Mustang to people in Turkey? It doesn't show Turkish people in the best light, but it's probably an accurate portrait of what's happened, right?

Deniz Gamze Ergüven: Right now Turkey feels as if we've been sailing through rapids and we don't know exactly what's going to happen at the next turn. It was already like that by the time we were making the film. At many moments I had the impression we were doing the title of Woody Allen's first movie Take the Money and Run. But it wasn't just about the money. We would shoot, take what we had, then run. Shoot some more, take what we had, then run. You have to navigate and know what's around you.

Feinberg: Has Mustang screened in Turkey?

Deniz Gamze Ergüven: It has screened in Turkey and was released in Turkey. The film is quite warmly embraced wherever it goes, though in Turkey the reactions were extremely polarized. It was either loved or hated, exuberantly expressed by both extremes, and nothing in the middle. The social attitude in Turkey is always extreme, and—to this day when I see the film myself—I think, "Oh, this is shocking." The film is deeply in sacred territory and is breaking down quite a few doors so the amount of reaction we are receiving is normal.

Feinberg: The last thing I would like to do up here is to talk about this period since you all got the news that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Foreign Language Committee deemed that out of dozens of films from around the world, you guys are the last standing. That's got to be an exciting thing for all of you and I wanted to pose a couple of questions to a few of you because I think it will help contextualize how historically significant it is for all of you but especially so in certain countries.

To begin with, Naji, Jordan has only submitted one film ever before, Captain Abu Raed in 2008, which did not advance. How does it feel to have advanced to the shortlist? How does it feel to take a film further than any other film that has come out of your country?

Naji Abu Nowar: It feels incredible. I live in Jordan so when the news came out my phone literally exploded. We don't really have an industry, just some passionate people walking through it together, and everyone on the crew jumped together and we had a party. Everyone's been going crazy on social media and Twitter. It's just been nuts! One of the really nice things that's happened with me is that people have come up to me off the street and said, "We don't have a lot to celebrate. Things are pretty bad at the moment, but we're rooting for you. This is a positive thing to come out of our country." That's been touching. It's been a hell of a ride.

Feinberg: Ciro, Colombia has submitted 23 films prior to this one, including two others of yours. This is the country's first to be shortlisted with the potential to be nominated. You're going where no other Colombian has gone before!

Ciro Guerra: This is a very special moment for us. This is the year where, finally, after 50 years of conflict, we're about to sign a peace agreement. It's a special moment full of hope. We didn't have cinema in Colombia 10 years ago. We only made about two films a year. And now we're at this moment where we're about to start looking back at the darkest period of our history. Cinema is hope, and a way of telling our stories: who are we in this context? There are a lot of young people who believe in cinema. Cinema has not been something which we've been allowed to be proud of in the past so this means a lot for the Colombian people. I hope to see the movies mean more than the awards, but it's a moment when—a lot of people who don't believe in Colombian cinema—are starting to believe. There's a reason to be optimistic.

Feinberg: Again, it's interesting because part of the thing about the Oscars® is that it gives us a look into each of your countries' cinematic histories. László, in the years since the fall of Communism it's been hit-or-miss for Hungarian cinema but you've restored a lot of excitement with your film. What's been the response back home to the acclaim Son of Saul has received?

László Nemes: Let me first give you some perspective on the film because I think it's interesting. This was my first film and nobody wanted to finance it. We tried throughout Europe with the French Film Fund, the Israel Film Fund, the Germans, the Austrians, nobody. When we finally made it, we submitted it to the Berlin Film Festival and they didn't want to take it in competition! Seventy years after the liberation of Auschwitz and Berlin didn't want to take this film into competition! It's not about any rights that I might have, but people see Son of Saul more as a subject than a film, you know?

Cannes took a huge risk to take this into competition, which they rarely do with a first feature. I feel this film came back from the dead, so now that we're in this campaign for the Oscars®, it feels magical and unreal at the same time. I know that Hungary has had a long tradition of filmmaking and Hollywood is partly founded by Hungarian Jews, so in a way we have it in our blood. At the same time, there's so much resistance. If you go to the street in Hungary, they'll ask, "Who is this Jew boy who wants to make a film? He's representing our country?!" There's so much resistance, and hate. It's been a conflicted story and I think it always will be; but, being part of the journey is incredible and I'm like a little boy in the candy store, impressed by it. It's great to meet these filmmakers from around the world so I'm thankful for that.

[A videocast of this "Talking Pictures" forum is available here.]

PSIFF 2016—A WAR (2015): Q&A With Tobias Lindholm

[Warning: This write-up contains spoilers.]

Danish filmmaker Tobias Lindholm is a contemporary master of suspense, both in his screenplays, which include The Hunt (Jagten, 2012)—brought to the screen by Thomas Vinterberg and starring Mads Mikkelson in a Hitchcockian scenario of a man wrongly accused of a crime—and in his own narrative features such as A Highjacking (Kapringen), also from 2012, which addressed tense negotiations with Somali pirates. Pilou Asbæk and Søren Malling, two of the actors featured in A Highjacking, have returned for Lindholm's follow-up military drama A War (Krigen, 2015), Denmark's official submission currently nominated for the Foreign Language Academy Award®. It screened in the Awards Buzz sidebar at the 2016 Palm Springs International Film Festival (PSIFF) with director Lindholm in attendance.

As synopsized by PSIFF: "The stakes are higher than ever in this tense and suspenseful drama as a well-liked Danish company commander is forced to choose between his responsibility for his troops, the Afghan locals, his family back in Denmark and the written and unwritten rules of war. While Commander Claus Michael Pedersen [Asbæk] and his men are stationed in an Afghan province, Claus's wife Maria [Tuva Novotny] is trying to hold everyday life together back in Denmark. Meanwhile, during a routine mission, the soldiers are caught in heavy crossfire. In order to save his men, Claus makes a decision that has grave consequences."

As aggregated by David Hudson at Fandor's Keyframe Daily, reviews from the film's premiere at the 2015 Venice Film Festival have been uniformly supportive, including Guy Lodge's write-up for Variety—"A rigorous, engrossing anatomy of a suspected war crime: In its nerve-shattering first half, it conveys the on-the-ground maelstrom of combat as vividly as any film on the subject. A War doesn't seek to break new ground in the ongoing cinematic investigation of the Afghanistan conflict; rather, it scrutinizes the ground on which it stands with consummate sensitivity and detail."—and Boyd van Hoeij for The Hollywood Reporter—"Almost as much time is spent with Pedersen's wife back home…. [W]hat interests Lindholm is what it means for a family when a vital component of it is absent for months on end; by contrasting Afghanistan and Denmark, a clearer picture emerges of what Claus does but also what he's missing and isn’t able to do, which is just as telling."

Lindholm reveals his skill for suspense by bifurcating the tension. The film's first half is on the ground in Afghanistan in harrowing crossfire with the Taliban, and in its second half in a rigorously modulated court hearing where Claus' field decisions come under fire from military prosecutors. It's hard to say which is more jangling on the nerves.

In his introduction to his PSIFF audience, Lindholm stated: "When I started to do this project, I knew that I needed real soldiers, not actors, to do the battle scenes, basically because I have never been a soldier and don't have the expertise so how would I be able to direct actors to move naturally as soldiers? It would be impossible."

That strategy proved invaluable in the film's re-enactment of the pivotal battle sequence where Pedersen gives the order to bomb a compound without first confirming enemy presence; a desperate effort to save the lives of his own men. As a result, eleven civilians are killed, including eight children. My question to Lindholm was one of craft. "How do you choreograph an action sequence like that?" I asked. "Do you use storyboards?" Having already confided that—not having been to war himself—he relied on soldier informants, I wanted to know about the nature of that reliance. Did he improvise scenes with them in order to construct such a complicated action sequence?

Lindholm repliled: "That's the great thing about soldiers; they know what to do. The actors just had to follow them. I would place huge loudspeakers just outside the wall and they would never know when the explosions would come, so they were reacting to the reality around them, as they do when they rehearse. Pilou just followed them. I remember we challenged Butcher, who is on the ground with the radio. I was doing all the radio communication live so I would have a soldier beside me at the monitor and he would ask questions and tend the orders and do stuff on the radio live with them. We kept pouring gasoline on the fire, saying, 'Call and tell him this, tell him that, let's see how he reacts. Push him!' Pilou got frustrated in the situation because he could feel that Butcher was frustrated and that spread among them.

"We actually didn't do any choreography. We just went out there and played it out. I knew where I had put the explosions. I knew when I wanted to push the button so that it would sound like bullets over their heads. They just reacted. That's the great thing about soldiers. They didn't know it, but they were great actors because they could reproduce the situation again and again and again. They've done that. That's their job: to be able to cope with chaos and do the same thing, the same drill, again and again and again. That's moviemaking! I relied on them and hoped to capture something that could feel real."

Lindholm qualified that he hunted out Danish veterans who had spent years of their lives in Afghanistan. He promised them that he would be honest with them all the way; that he wouldn't lie; that he wouldn't change anything to make them look morally bad or good; but, would portray them as honestly as he could. "Now the honesty thing, I've kept," he added in his introduction, "but, after the film, you can tell me if they look good or not."

Which becomes the film's spectatorial conundrum. "It's frankly difficult to imagine a more generic setup for a contemporary war movie," writes Tommaso Tocci at The Film Stage, "but if there's one director that can make the how more compelling than the what, it is Lindholm." As a film, yes, A War is competently constructed. Its subject matter, however, remains morally problematic for rallying behind a brothers-in-arms mentality that effectively skirts (and justifies?) the war crime of civilian casualties. Yet, as honest as Lindholm endeavored to be with the soldiers who appeared in his film, he is no less transparent with his audience.

When asked how he developed the script—whether he started from a basic premise and then followed up with interviews to confirm his premise or whether his interviews inspired the script from the get-go—Lindholm answered amusingly that he started with wondering about his mother, who he loves very much, but who is a classic Scandinavian Socialist. She raised him with the belief that rich people were rich because they've stolen money from poor people and—although he's not sure if that's the truth—it was part of the questioning cultural zeitgeist in Denmark in the 1960s. She also raised him with the idea that war was evil and that soldiers, by extension, were evil; an idea he wanted to confront. In gist, he wanted to create a story that would make his mother cheer for a war criminal. He figured if he could pull that off, then he would have negotiated the central challenge of the film.

In order to achieve that, his starting point was to introduce Lasse, a broken-down young soldier wanting to return home after watching his best friend die from an IED explosion. His commanding officer Pedersen can't allow that, of course, but—when Lasse gets shot—the audience begins to understand why Pedersen struggles to save him, his reasoning, and why his actions feel necessary. "It's a bit technical," Lindholm explained, "but I'm always looking for a middle point and a fake ending. If we know the beginning, the middle point, and the fake ending, then the whole story's there." In this case, the beginning is Lasse's breakdown after witnessing his friend's death. The middle point is Pederson ordering the bombing. The fake ending, of course, is his admittance of the crime. With those points to write through, Lindholm felt confident in his narrative and could then conduct interviews to secure requisite information, including the logic of the military worldview.

Thus, A War is based on a combination of true events and not one person's nightmarish account, which Lindholm would have considered parasitic. He knew he wanted to make a film about this war; the first war that Denmark has fought since the Second World War (which lasted all of four-five hours). This war has in many ways defined Lindholm's generation; but, at first, he couldn't find his way in. "We've often seen a lot of war films," Lindholm offered, "where you follow the dehumanization of as young man from the minute he goes to war and then you see how he'll fall apart as a human being in that process. I felt that story had been told already. Then I read an interview with a Danish officer going back on his third tour to Afghanistan where he said, 'I'm not afraid of getting killed down there; I'm afraid of being prosecuted when I get back home because the rules of engagement and doing my job are in conflict.' That, right there, was when I knew I had a story and where I wanted to go." He started talking to everyone who had been involved in trials—the prosecutors, the defense lawyers, everybody who knew about them—to try to find a case situation or legal conflict that would be so precise that everyone could understand Andersen's essential conflict: not only why he did what he did, but recognizing at the same time that it was a war crime.

At this juncture, Lindholm's filmic enterprise borders on Dostoyevsky in its examination of the definition of crime itself and how apparent crimes are often predicated on equally criminal forces operating behind the scenes, avoiding culpability by redirecting punishment. Suddenly the question becomes what was the "mission" of Denmark's presence in Afghanistan?

"Originally we went in to hunt down bad guys," Lindholm synopsized. Following 9/11, together with the U.S. and the U.K., special troops went in to Afghanistan right away on the clear logic—neither good nor bad, but logical—to try to kill the bad guys. This clear purpose morphed into abstraction as it soon became clear that Danish forces were not there to fight; they were there to walk around in an area and, once in a while, step on an IED or get shot. The fact that they were there became the mission, even if they also became walking targets for the Taliban.

Conceding that the military may have had good reasons for this "mission", it nonetheless became difficult to reconcile their logic with the hazard of walking out the gates of the military compound, fully aware of the danger of IEDs and snipers. Danish military were encouraged to enter Afghan villages and befriend villagers, even if they knew it wasn’t helping the villagers and that—once they left—the Taliban returned. That being said, villagers never escaped the taint of collaborating with the Taliban. That informed the scene where the Afghan family is turned away from the military compound. Lindholm had originally included an explanation in the script, but found the scene too obvious in the editing room. If you apply military logic, of course the soldiers could not let the Afghan family into their compound. What if they were Taliban? If they were let in, they would see how everything looks, how everything works. It's not a refugee camp. The political reason that the soldiers are there is to keep the Afghan locals in the villages and protect them against Taliban. If they started inviting them into their camp, they wouldn’t be doing their job. They were under orders to keep the Afghans in their own villages. Besides, even if they made an exception, where would it stop? What would be allowed for the next family? And the next?

Real soldiers were used in filming that scene, including the female translator who had served in Afghanistan a couple of times. The family were from the Helmand Province. They escaped the war, lived in a refugee camp and knew all too well the situation of the family in the film. On the day of shooting, they became extremely emotional. Lindholm seeks to create scenarios that play out as if real, inflected by a documentary impulse, albeit controlled. In this case, he gave the scene a long time to shoot. He respected that the Afghan family had never acted before. For them, as well as the female translator, the scene became real. Her frustration in having to send them back to their village was tangible for her, energized by accumulated experiences from her two deployments.

Lindholm recalled when Danish military proposed as their rationale what they called "the ink drop principle" where you'd take a pen and make arbitrary “drops” on a map: “Let's pick a place here for a liberation base and just have 100-150 guys living there and patrolling the area." But not really fighting an enemy, not really doing too much. Within the idea of befriending the locals, “not doing too much” meant the rules of engagement became increasingly complicated and difficult. Soldiers had to have really good reasons to shoot, which meant that—in the case of the film’s sniper scene with the guy on the motorbike—it's pretty clear to everybody what's going on; but, a soldier has to be absolutely certain that someone’s a bad guy before he can shoot him. Maybe such safeguards are the right thing to do?

“I'm not the judge of that,” Lindholm insisted, adding, “I can only imagine how frustrating it must be to walk out that gate every day not exactly knowing why you're there. The reason that you're there will become to protect your friends.” That's what Andersen does all the way through, and why Lindholm accepts that Butcher lies in court to protect his commander. “That's what he's trained to do.” Lindholm achieves his task of garnering support for Andersen, and asks (without answering) the underlying question: was it the right thing to do to cover up a war crime in order to protect a friend?

The sad truth is that in just the past few months the Helmand Province has fallen back into Taliban hands, which has caused much public discussion in Denmark: “Why has this happened? Why were we even there? Do we have to go back in to try to clean it up? What's happening?” This public uncertainty characterizes the situation in Denmark at this time, and is envisioned in A War’s final scene where Andersen is shown sitting on his back deck smoking a cigarette. After what he has experienced, can he ever truly return to civilian life? Though Denmark’s soldiers have been called home, the Danish now have the difficult task of reflecting on why Denmark was in Afghanistan in the first place and what actually happened? These questions are challenging Denmark’s democracy in much the same way that opposition has articulated itself in the U.S.

“We are in what you would call a small-scale post-Vietnam phase in Denmark right now,” Lindholm explained. “We're trying to figure out what kind of people we are and how our democracy can continue with this happening at the same time? That was the reason for me to make this film in the first place.” The final image of Andersen reflecting on his deck suggests questions that won’t be answered for a long time. His doubts and regrets will probably haunt him for the rest of his life.

Perhaps not so surprisingly, most of the questions following Lindholm’s PSIFF screening had to do with Andersen’s military trial. How could a civilian trial judge military misconduct? Does the verdict in a civil trial have to be unanimous?

One of the problems of being a young warfaring nation, Lindholm responded, is trying to figure out how to deal with war crimes. Admittedly shocked that a civilian court would oversee such a process, Lindholm learned that the prosecutor is from the military hired by the military to work in these courts. The rest are civilians who have no to little idea what military engagement entails. What happened in Denmark, Lindholm explained, and what is happening right now, is that the politicians who sent these young people to war need to wash their hands as they say, "Yes, we went out to war but we would never accept war crimes." The whole idea for Lindholm is a strange thought that you would create something as chaotic as war and then think that you could sit back in Denmark and make laws about it as if you understood what armed conflict really is? At the same time, as a democracy, they need these trials because, of course, it wouldn't be possible to let military do their jobs without there being some sort of control, some rules of engagement; but, the idea of civilians being able to cope, understand and judge military misbehavior is absurd and a huge problem in a democracy like Denmark.

The verdict in a civil trial does not have to be unanimous. It can be two to one. It frustrated Lindholm to discover that within Denmark’s system the panel hearing such cases is composed of two civilians and one judge, but the judge’s opinion doesn’t count any more than the other two. The defendant can, of course, appeal and have the case go into the system; but, ordinarily, they try to keep it simple. A fun story is that the judge in Lindholm’s film is a real judge. She went on pension just a week before he started to shoot. “And I can tell you,” he grinned, “she didn't take direction from anybody. That was her courtroom. I took direction from her.”

Danish filmmaker Tobias Lindholm is a contemporary master of suspense, both in his screenplays, which include The Hunt (Jagten, 2012)—brought to the screen by Thomas Vinterberg and starring Mads Mikkelson in a Hitchcockian scenario of a man wrongly accused of a crime—and in his own narrative features such as A Highjacking (Kapringen), also from 2012, which addressed tense negotiations with Somali pirates. Pilou Asbæk and Søren Malling, two of the actors featured in A Highjacking, have returned for Lindholm's follow-up military drama A War (Krigen, 2015), Denmark's official submission currently nominated for the Foreign Language Academy Award®. It screened in the Awards Buzz sidebar at the 2016 Palm Springs International Film Festival (PSIFF) with director Lindholm in attendance.

As synopsized by PSIFF: "The stakes are higher than ever in this tense and suspenseful drama as a well-liked Danish company commander is forced to choose between his responsibility for his troops, the Afghan locals, his family back in Denmark and the written and unwritten rules of war. While Commander Claus Michael Pedersen [Asbæk] and his men are stationed in an Afghan province, Claus's wife Maria [Tuva Novotny] is trying to hold everyday life together back in Denmark. Meanwhile, during a routine mission, the soldiers are caught in heavy crossfire. In order to save his men, Claus makes a decision that has grave consequences."

As aggregated by David Hudson at Fandor's Keyframe Daily, reviews from the film's premiere at the 2015 Venice Film Festival have been uniformly supportive, including Guy Lodge's write-up for Variety—"A rigorous, engrossing anatomy of a suspected war crime: In its nerve-shattering first half, it conveys the on-the-ground maelstrom of combat as vividly as any film on the subject. A War doesn't seek to break new ground in the ongoing cinematic investigation of the Afghanistan conflict; rather, it scrutinizes the ground on which it stands with consummate sensitivity and detail."—and Boyd van Hoeij for The Hollywood Reporter—"Almost as much time is spent with Pedersen's wife back home…. [W]hat interests Lindholm is what it means for a family when a vital component of it is absent for months on end; by contrasting Afghanistan and Denmark, a clearer picture emerges of what Claus does but also what he's missing and isn’t able to do, which is just as telling."

In his introduction to his PSIFF audience, Lindholm stated: "When I started to do this project, I knew that I needed real soldiers, not actors, to do the battle scenes, basically because I have never been a soldier and don't have the expertise so how would I be able to direct actors to move naturally as soldiers? It would be impossible."

That strategy proved invaluable in the film's re-enactment of the pivotal battle sequence where Pedersen gives the order to bomb a compound without first confirming enemy presence; a desperate effort to save the lives of his own men. As a result, eleven civilians are killed, including eight children. My question to Lindholm was one of craft. "How do you choreograph an action sequence like that?" I asked. "Do you use storyboards?" Having already confided that—not having been to war himself—he relied on soldier informants, I wanted to know about the nature of that reliance. Did he improvise scenes with them in order to construct such a complicated action sequence?

Lindholm repliled: "That's the great thing about soldiers; they know what to do. The actors just had to follow them. I would place huge loudspeakers just outside the wall and they would never know when the explosions would come, so they were reacting to the reality around them, as they do when they rehearse. Pilou just followed them. I remember we challenged Butcher, who is on the ground with the radio. I was doing all the radio communication live so I would have a soldier beside me at the monitor and he would ask questions and tend the orders and do stuff on the radio live with them. We kept pouring gasoline on the fire, saying, 'Call and tell him this, tell him that, let's see how he reacts. Push him!' Pilou got frustrated in the situation because he could feel that Butcher was frustrated and that spread among them.

"We actually didn't do any choreography. We just went out there and played it out. I knew where I had put the explosions. I knew when I wanted to push the button so that it would sound like bullets over their heads. They just reacted. That's the great thing about soldiers. They didn't know it, but they were great actors because they could reproduce the situation again and again and again. They've done that. That's their job: to be able to cope with chaos and do the same thing, the same drill, again and again and again. That's moviemaking! I relied on them and hoped to capture something that could feel real."

Lindholm qualified that he hunted out Danish veterans who had spent years of their lives in Afghanistan. He promised them that he would be honest with them all the way; that he wouldn't lie; that he wouldn't change anything to make them look morally bad or good; but, would portray them as honestly as he could. "Now the honesty thing, I've kept," he added in his introduction, "but, after the film, you can tell me if they look good or not."

Which becomes the film's spectatorial conundrum. "It's frankly difficult to imagine a more generic setup for a contemporary war movie," writes Tommaso Tocci at The Film Stage, "but if there's one director that can make the how more compelling than the what, it is Lindholm." As a film, yes, A War is competently constructed. Its subject matter, however, remains morally problematic for rallying behind a brothers-in-arms mentality that effectively skirts (and justifies?) the war crime of civilian casualties. Yet, as honest as Lindholm endeavored to be with the soldiers who appeared in his film, he is no less transparent with his audience.

When asked how he developed the script—whether he started from a basic premise and then followed up with interviews to confirm his premise or whether his interviews inspired the script from the get-go—Lindholm answered amusingly that he started with wondering about his mother, who he loves very much, but who is a classic Scandinavian Socialist. She raised him with the belief that rich people were rich because they've stolen money from poor people and—although he's not sure if that's the truth—it was part of the questioning cultural zeitgeist in Denmark in the 1960s. She also raised him with the idea that war was evil and that soldiers, by extension, were evil; an idea he wanted to confront. In gist, he wanted to create a story that would make his mother cheer for a war criminal. He figured if he could pull that off, then he would have negotiated the central challenge of the film.

In order to achieve that, his starting point was to introduce Lasse, a broken-down young soldier wanting to return home after watching his best friend die from an IED explosion. His commanding officer Pedersen can't allow that, of course, but—when Lasse gets shot—the audience begins to understand why Pedersen struggles to save him, his reasoning, and why his actions feel necessary. "It's a bit technical," Lindholm explained, "but I'm always looking for a middle point and a fake ending. If we know the beginning, the middle point, and the fake ending, then the whole story's there." In this case, the beginning is Lasse's breakdown after witnessing his friend's death. The middle point is Pederson ordering the bombing. The fake ending, of course, is his admittance of the crime. With those points to write through, Lindholm felt confident in his narrative and could then conduct interviews to secure requisite information, including the logic of the military worldview.

Thus, A War is based on a combination of true events and not one person's nightmarish account, which Lindholm would have considered parasitic. He knew he wanted to make a film about this war; the first war that Denmark has fought since the Second World War (which lasted all of four-five hours). This war has in many ways defined Lindholm's generation; but, at first, he couldn't find his way in. "We've often seen a lot of war films," Lindholm offered, "where you follow the dehumanization of as young man from the minute he goes to war and then you see how he'll fall apart as a human being in that process. I felt that story had been told already. Then I read an interview with a Danish officer going back on his third tour to Afghanistan where he said, 'I'm not afraid of getting killed down there; I'm afraid of being prosecuted when I get back home because the rules of engagement and doing my job are in conflict.' That, right there, was when I knew I had a story and where I wanted to go." He started talking to everyone who had been involved in trials—the prosecutors, the defense lawyers, everybody who knew about them—to try to find a case situation or legal conflict that would be so precise that everyone could understand Andersen's essential conflict: not only why he did what he did, but recognizing at the same time that it was a war crime.

At this juncture, Lindholm's filmic enterprise borders on Dostoyevsky in its examination of the definition of crime itself and how apparent crimes are often predicated on equally criminal forces operating behind the scenes, avoiding culpability by redirecting punishment. Suddenly the question becomes what was the "mission" of Denmark's presence in Afghanistan?

"Originally we went in to hunt down bad guys," Lindholm synopsized. Following 9/11, together with the U.S. and the U.K., special troops went in to Afghanistan right away on the clear logic—neither good nor bad, but logical—to try to kill the bad guys. This clear purpose morphed into abstraction as it soon became clear that Danish forces were not there to fight; they were there to walk around in an area and, once in a while, step on an IED or get shot. The fact that they were there became the mission, even if they also became walking targets for the Taliban.

Conceding that the military may have had good reasons for this "mission", it nonetheless became difficult to reconcile their logic with the hazard of walking out the gates of the military compound, fully aware of the danger of IEDs and snipers. Danish military were encouraged to enter Afghan villages and befriend villagers, even if they knew it wasn’t helping the villagers and that—once they left—the Taliban returned. That being said, villagers never escaped the taint of collaborating with the Taliban. That informed the scene where the Afghan family is turned away from the military compound. Lindholm had originally included an explanation in the script, but found the scene too obvious in the editing room. If you apply military logic, of course the soldiers could not let the Afghan family into their compound. What if they were Taliban? If they were let in, they would see how everything looks, how everything works. It's not a refugee camp. The political reason that the soldiers are there is to keep the Afghan locals in the villages and protect them against Taliban. If they started inviting them into their camp, they wouldn’t be doing their job. They were under orders to keep the Afghans in their own villages. Besides, even if they made an exception, where would it stop? What would be allowed for the next family? And the next?

Real soldiers were used in filming that scene, including the female translator who had served in Afghanistan a couple of times. The family were from the Helmand Province. They escaped the war, lived in a refugee camp and knew all too well the situation of the family in the film. On the day of shooting, they became extremely emotional. Lindholm seeks to create scenarios that play out as if real, inflected by a documentary impulse, albeit controlled. In this case, he gave the scene a long time to shoot. He respected that the Afghan family had never acted before. For them, as well as the female translator, the scene became real. Her frustration in having to send them back to their village was tangible for her, energized by accumulated experiences from her two deployments.

Lindholm recalled when Danish military proposed as their rationale what they called "the ink drop principle" where you'd take a pen and make arbitrary “drops” on a map: “Let's pick a place here for a liberation base and just have 100-150 guys living there and patrolling the area." But not really fighting an enemy, not really doing too much. Within the idea of befriending the locals, “not doing too much” meant the rules of engagement became increasingly complicated and difficult. Soldiers had to have really good reasons to shoot, which meant that—in the case of the film’s sniper scene with the guy on the motorbike—it's pretty clear to everybody what's going on; but, a soldier has to be absolutely certain that someone’s a bad guy before he can shoot him. Maybe such safeguards are the right thing to do?

“I'm not the judge of that,” Lindholm insisted, adding, “I can only imagine how frustrating it must be to walk out that gate every day not exactly knowing why you're there. The reason that you're there will become to protect your friends.” That's what Andersen does all the way through, and why Lindholm accepts that Butcher lies in court to protect his commander. “That's what he's trained to do.” Lindholm achieves his task of garnering support for Andersen, and asks (without answering) the underlying question: was it the right thing to do to cover up a war crime in order to protect a friend?