During my recent stay in San Francisco I had the opportunity to attend two separate events showcasing the short films of Curt McDowell. The first—under the aegis of the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts' seventh edition of Bay Area Now (BAN7) and in collaboration with [ 2nd floor projects ]—was a program of five shorts, screened in conjunction with the BAN7 exhibition EROS / ON. The second was a companion event at the Roxie Theater screening two more of McDowell's rarely-seen short films.

As synopsized by YBCA, Curt McDowell (1945–1987) was a filmmaker, actor, visual artist, and writer. He arrived in San Francisco in the mid-1960s to attend the San Francisco Art Institute in the painting department and quickly changed course to become a filmmaker to work with George Kuchar, within a period that witnessed the Summer of Love, gay liberation, and the onset of AIDS, to which he succumbed at the age of 42. The author of numerous films that recast the American dream of plenty in pansexual terms, McDowell, like so many artists of his generation, indulged in the era's carnal abundance, and his appetites and experiences are reflected in the work. Thundercrack! (1975), his well-known feature, was cowritten with George Kuchar. He directed over 30 films, such as Confessions (1971), Weiners and Buns Musical (1972), Loads (1980), and Sparkle's Tavern (1985), celebrating sex as well as genre riffing and autobiographical narratives that bear the influences of Jack Smith's lush, DIY camp aesthetic; Rainer Werner Fassbinder's explosive melodrama; and Nan Goldin's glimpses of countercultural bohemia. McDowell had a vast history with 101-year-old Roxie Theater in San Francisco. The theater was reinvented in the 1970s as a vital repertory and alternative first-run cinema by his partner Robert Evans, along with Bill Banning, Peter Moore, and Anita Monga.

Melinda McDowell [Milks], Curt's sibling and an actor in many of his films, was present to introduce both programs and to engage in Q&As at both venues. She qualified when she took to the YBCA screening room stage that she was not so good at coming up with things to say about her brother's films and was better at answering questions about them. "Because I know the answers." Pulling a list of the evening's scheduled films from her purse, she asserted how fortunate an audience we were to be able to see a rarely-seen video by George Kuchar that he made for a one-off show in Chicago a few years ago. No one but her has a copy. Melinda didn't know Kuchar had made this video until she attended the show in Chicago, which featured some of Kuchar's films along with McDowell's. The video is basically Kuchar talking about McDowell and introducing him to a film-viewing public who might not know much about him, including mention of their own romance. People who knew both of them, Melinda asserted, would find this video of special interest because of the opportunity to hear George's side of his interaction with McDowell.

As for McDowell's short film Confessions (1972), Melinda confirmed that her brother was literally confessing to their parents and telling them in detail every bad thing he'd ever done. Asked if her parents ever saw Confessions, Melinda answered no, of course not. "They would have been horrified." As insight into the film, Melinda noted that the patchwork quilt Curt lies on while confessing to their mom and dad was made by their mom, who also wrote the lyrics to the music playing in the background. Curt was a sentimental, loving son, Melinda insisted, and Confessions wasn't made out of disrespect. Rather, it was made out of respect for their Mom, who he loved.

In his lovely broadsheet / chapbook written to accompany the selection of films in the [ 2nd floor projects ] screening, Johnny Ray Huston recalls: "I saw Confessions for the first time, and it put the world together for me, breaking through silence and leaping across states to share three-ways and four-ways and so many secret jewels of experience with mom and dad." And asks: "How much joy and lust and friendship can be crammed into one 16-minute movie? 'To put it into words is just not that easy to do.' After a tearful confession, Curt casts one true love as a leading man and lets the images do most of the talking, so what you know about him is felt. The difference between a messy guy in bloom and a perfect lifeless doll. The beauty of women's faces and men's cocks in close-up, and dirty bare feet, stepping forward. A live-wire radio built by editing that switches from folk to blues in a heartbeat. Fanfare, a cum shot, and a burst of applause as the director walks away from the camera, into San Francisco daylight. There's no happier ending in cinema."

With regard to the third film on the program, Ronnie (1972), Melinda advised that Ronnie, the young man who is the subject of the film, never had a clue that anyone would ever actually be watching the film. He thought he was just doing something for a little bit of money that day and that would be the end of it. "Boy, was he wrong," Melinda laughed, "because so many people have seen Ronnie." But he never knew. Though he'd be an older man now, Melinda expressed interest in seeing him again to say hi, if anyone knew how to locate him. Watching Ronnie, Melinda said she holds her breath throughout the entire film.

Huston writes of Ronnie: "Ronnie shaving, the camera staring down at his tight torso. Ronnie lighting a cigarette, a valentine heart tattooed on his forearm, a man on a horse dangling from his necklace, and his tighty-whiteys peaking out over his khakis. Ronnie reclining on the hardwood floor. Ronnie standing erect as the camera glides up and down his body, from his stout face to the shiny black boots on his feet. Ronnie scratching his cock. Ronnie naked in monologue in front of the window overlooking the street, the camera looking up from between his legs. Ronnie with his hands held behind him, a belt welt on his hairy, meaty right cheek. Ronnie on his elbows, laying stomach down on the floor, his back arched and his legs spread to show off his glorious ass.

"Ronnie, 'a very fussy guy' who doesn't 'believe in letters,' but who is writing a book he hopes will be a 'good seller,' titled Black and White. Ronnie, who wishes 'the Lord could come down off the cross and change things.' Ronnie, who still could have been a model for Old Reliable, or the subject of a story in Boyd McDonald's Straight to Hell, if he wasn't lucky enough to be immortalized as the star of Ronnie, a gorgeous black-and-white movie directed by Curt McDowell."

The evening's fourth film, A Visit to Indiana (1970), has received a response over the years that Curt would never have dreamed possible. That it would be purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, that it would be included in the Library of Congress, Curt would not have had a clue that the film would come to be seen as a social commentary.

As for the final film of the evening, Boggy Depot (1973), Melinda was convinced curator Margaret Tedesco included it in the program specifically because it's one of Melinda's favorites. A musical, Boggy Depot starts Curt, George Kuchar, and Ainslie Pryor, a beautiful young lady who starred in several of Curt's and George's films. Johnny Ray Huston asked Melinda if she could talk about the songs in Boggy Depot, "because I really love them and they're hilarious." Melinda admitted to loving all of Curt's musicals. Weiners and Buns (1972) is another of her favorites. She said Curt and Mark Ellinger loved to make those songs together. She has numerous reel-to-reel tapes of the songs those two wrote together, though she wasn't actually there during the songwriting sessions and wasn't personally involved.

Curt made a lot of his short films as a consequence of the fact that film was expensive. If he was working on a bigger project like the 60-minute Peed Into the Wind (1972), or any of the films that were a little bit longer, if there was any film left at the end of the roll he wanted to use it up, every inch of it, so he would come up with some short film written right then and there.

To wrap up the program, they included the five-minute Thundercrack! trailer narrated by George Kuchar, partly to entice the audience to purchase the DVD next year when it's finally released to celebrate the film's 40th anniversary. Melinda promised a great DVD release party that everyone could attend.

Asked if Curt knew about George before he met him, Melinda confirmed that, yes, Curt had heard of George, was his champion, and even had something to do with George coming to teach at the San Francisco Art Institute. George left the Bronx behind, came to San Francisco, and stayed.

Admitting that Curt had kept explicit diaries since the age of 17, I asked if any of that material was going to be made available? "Heck no," Melinda answered, explaining that in his diaries Curt revealed every detail of every encounter with every person, naming names. For all the time that she was with him, Curt wrote about her in his diaries like they were her diaries too. She wouldn't have let anything be published about George because George was private. Curt wasn't. He didn't care who read his diary entries. If it was up to Curt, he would have had the diaries published; but, Melinda was concerned with liability and privacy issues about all of the people written about in the diaries, since Curt was admittedly promiscuous. She's sure many of those people would not want to be named. Even if she changed their names, people would be able to figure out who was who.

Margaret Tedesco brought up the fact that Curt's prolific output as an artist was made all the more remarkable for recognizing that he was blind in one eye. It gave him an advantage, Melinda suggested, because—when you look with two eyes—an image is three-dimensional. With one eye, an image is not three-dimensional and much easier to render two-dimensionally on paper, creating an illusion of three-dimensionality, which worked for him. Being blind in one eye was not a drawback for him. Further, as one could guess, Curt was quite the voyeur but binoculars were of no use to him. Melinda bought him a monocular and he was so proud of it and enjoyed it immensely. He could look out the window at guys across the street.

One piece of good news Melinda shared with her YBCA audience was that Mark Toscano, an archivist of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences—and formerly involved with Canyon Cinema—asked the Academy 10 years back if they would be interested in having Curt's films restored and preserved at the Academy and having new prints struck? They said no, of course not, no, because of the content. But just recently Melinda found out that the Academy has changed its mind, perhaps due to new blood, and has asked for all of Curt's films—including ones most people haven't even seen yet—to preserve them at the Academy.

A week or so later, Melinda was present to introduce a second set of Curt McDowell films at the Roxie Theater, specifically Taboo: The Single and the LP (1980), which Curt made based on some bizarre graffiti he discovered first in one restroom, then another, and then another, all around San Francisco. He couldn't help himself and had to make a film about the Abner family referenced in this graffiti, which included statements like "Abner slapped hard like blue magic." So Curt created a character named Blue Magic. The characters in Taboo, in fact, enact statements made in the graffiti. But the mystery remains: "Who wrote the graffiti?" There were only the three members of the family: Abner, Dorothy and Mary. Recently, Melinda determined through a Google search that they were real people. She found the gravestone of Abner and Dorothy and discovered that Mary—the part she played in the film—is alive and living near her. Mary would be 74 now, and though Melinda has never met her, she feels Mary would be horrified with Curt's interpretation of her family in Taboo. With that in mind, Melinda said we would be seeing familiar faces—George Kuchar, Marion Eaton, and herself—in this "strange little film."

Melinda isn't quite sure what Curt was trying to do with Taboo and asked her audience to give her a clue if they knew. What is clear is that Curt had a crush on Fahed Martin and wanted to see more of him, literally. The film might have been an excuse for that. George had shown her drawings and pictures Curt had made of this young man. He was clearly having a great time interacting with Fahed and making Taboo gave him a chance to film him scantily clad in wet pants.

Asked about Curt's involvement with the Roxie, Melinda recalled that he worked at the theater for many years. But he also fell in love and married Robert Evans, one of the original owners of the Roxie.

Sparkle's Tavern is another McDowell film that few people have seen. "Let's talk about what it is and what it isn't," Melinda suggested. It is not like Thundercrack! There are no hardcore scenes in Sparkle's Tavern. When Curt decided he wanted to make this film, he asked Melinda what her main fantasy was. She had just recently returned from Wyoming and she told him that her fantasy was to be in a room full of cowboys who all wanted her. So he made that happen in the film. What the film turned into, however, was a more personal story for Curt. He represented himself and Melinda as the brother and sister in Sparkle's Tavern whose naughtiness reflected their personal naughtiness in making films like Thundercrack!, etc. But what it was really about was Curt's desire to be publicly accepted by his parents. Even though he knew they loved him very much, he wanted to be acknowledged in public by them, which was hard for them to do at the time. What he created was a story that had this happy ending.

Melinda apologized after the screening for her performance in Sparkle's Tavern, reminding us she was not really an actress. "I'm not sorry I'm in it," she said, "just sorry you had to see it." She hoped we could get past her performance to see what the film was supposed to be. She praised Connie Richmond's performance as Brenda. And George Kuchar's performance as Mr. Pupik. She asked if anyone knew what "pupik" meant? In Yiddish, it means "belly button."

Melinda mentioned the scene with Brandon where she's lying on her bed crying. She didn't know how to cry for the camera so they literally shoved an onion under her pillow. But the tears at the end of the film were real because the little note she's handed in the scene was written by George who said, "There is shit on your shoe." He had to know that would make her cry. Curt didn't know why she was really crying at the end of that scene. He asked if she wanted to stop filming but she said no, and encouraged him to keep filming while she was crying (even if it was because of the note).

As for working with Marion Eaton, Melinda described her as being exceptionally professional and knowing all her lines at all times. She wanted to be like Melinda and Curt's mother and tried her best. She's local so she couldn't capture the true Midwestern accent their mother had, but she tried. Melinda never wanted to tell her that she didn't sound anything like their mother because she thought Marion's performance was great just the way it was.

A piece of good news Melinda recently discovered is that—out of the 65 films that the National Film Preservation Foundation have chosen to preserve this year—one of them is Sparkle's Tavern. Curt never would have dreamed that would happen and that Sparkle's Tavern would have been chosen to be preserved for posterity. He would have been so honored.

Once Melinda opened it up to the audience, I was quick to assert that—despite her own humility towards her acting chops—she was a radiant presence on the screen. Melinda said my comment made her "a smiling fool." My question, however, was about the film's spectacular costumes, especially her final costume. Curt created the costume, she answered, and she still has it, though admitting she can't fit into it anymore. It was unquestionably a spectacular creation with its Elizabethan stand-up collar and hand-beading.

One final piece of news is that—in preparing Thundercrack! for its DVD release, and its inclusion in the Academy archives—she came across some footage in the short print of Thundercrack! that had not been included in the long print. She explained that when Thundercrack! was experiencing its cult status at midnight movies, it was considered a little too long and was cut down to accommodate midnight crowds. That left only one long print. Making the situation even more problematic, Melinda recalled that several of the traveling prints of Thundercrack! were confiscated. The first time Curt took the film into England he had no trouble because he had written on the label of the film cannister: Thundercrack! Weather Conditions of the Southwest United States. They let it in. They didn't know. But the second time he tried to get into England with the film, they confiscated it at the border. Another time, the film was pulled out of the projector by the Montreal police at a film festival. So several of the prints have been lost and the effort is to compile one final version from all the elements left.

Of Thundercrack!, Johnny Ray Huston writes: "Though Thundercrack! is as unique as a pair of George Washington peepholes, it has deep roots in horror and comedy. The film's orgiastic cast are free-love descendants of the frighteningly funny eccentrics in James Whale's The Old Dark House. Its trip to a haunted house is a Midwestern rite of passage."

[My thanks to Johnny Ray Huston for permission to replicate passages from his broadsheet / chapbook entitled "the single and the LP" and lovingly inscribed, "For Michael, my compadre!" Johnny Ray's broadsheet is available for PDF download here.]

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

SEISMOGRAPH OF AN ERA—The Evening Class Interview With Peter von Bagh

The 56th San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF56) presented its 2013 Mel Novikoff Award to legendary cinephile Peter von Bagh for his lifelong commitment to international film, accompanied by an onstage conversation with Anita Monga and a screening of Helsinki, Forever (Finland, 2008), von Bagh's ode to Finland's capital and its cinema. SFIFF56 likewise screened Mikko Niskanen's Eight Deadly Shots (Finland, 1972), a rarely seen epic drama, considered by many a lost masterpiece of Finnish cinema and personally selected by von Bagh for its U.S. premiere at the festival.

"Peter von Bagh embodies the essence of the Mel Novikoff Award," said Rachel Rosen, San Francisco Film Society's director of programming. "He has worked indefatigably and infectiously to share his appreciation of world cinema and has many good stories to share about the filmmakers and icons he's met during his half century in the movies."

Throughout his career Peter von Bagh wore many different hats in the cinematic arena. Besides being a film director, one especially attracted to compilation films, von Bagh had been a television and radio producer, book publisher, curator and program director of the Finnish Film Archive, professor of film history, artistic director and cofounder of the Midnight Sun Film Festival and artistic director of Bologna's Il Cinema Ritrovato festival. As a film critic and historian, he (co)wrote and/or (co)edited more than 30 books, including The History of World Cinema, 1975 and 1998. Regarded as a Finnish national treasure, von Bagh is a true master of international film and an extraordinary example of cinema lived to the fullest.

With both SFIFF56 screenings of Helsinki, Forever and Eight Deadly Shots, I was keenly aware of something von Bagh articulated in his documentary Sodankylä Forever (Finland, 2010-2011): "Film screenings, like films themselves, are part of history; the seismograph of the era." With his passing earlier this week, I recall the privilege of speaking with von Bagh when he was in San Francisco in 2013 to receive the Mel Novikoff Award. He was unpretentious and generous with his intellect and gifted me the four-DVD set of Sodankylä Forever; one of the treasures in my library. My thanks go out to Bill Proctor of the San Francisco Film Society for facilitating our conversation.

Michael Guillén: First and foremost, congratulations on receiving the Mel Novikoff Award from the San Francisco Film Society.

Peter von Bagh: Thank you.

Guillén: One of my predominant interests is in film festival culture and I thought you would be the perfect person to talk to about that.

Von Bagh: That's okay, but with the strong limitation that I don't go to film festivals. I don't like them, though I run a couple of them.

Guillén: Let's talk a bit about the two festivals you run. Can you synopsize for me their singular focus? How long you've been working with each? And how you were drawn into running them when, as you confess, you don't like film festivals?

Von Bagh: In Finland it was more natural in a way because I was programming for the Finnish Film Archive [the National Audiovisual Institute of Finland] for 20 years or so. I started there in 1967 and was programming there all the time until the mid-80s. Originally, I was the Executive Director of the Archive but then I concentrated on programming because I felt that was my thing—I didn't want to go to meetings or anything—so I had that background.

Then I finished at the Finnish Film Archive in 1985, which was very sad for me. I was programming even in my dreams and had no outlets for my thoughts. But that same year Anssi Mänttäri, a Finnish director, was in a small village in the north out in the middle of nowhere—I don't know why—and it was November and all dark. Anssi was probably drunk and was looking out the window at ... nothing. Even during the daytime there were no people around, just emptiness. Then he came up with the idea: "Why not start an international film festival here?" Certainly, the most absurd of all origins for a festival. He was associated with two emerging talents of the time, Mika and Aki Kaurismäki, there were the three of them, and Anssi contacted me and asked me if I would like to become the director of the festival? That's how the Midnight Sun Film Festival started.

At first, I doubted the idea could work. I felt it was too absurd to travel so far for a film festival. But within a month I agreed to do it. We already had good contacts. I had been around for a while with the Archive and had already published Elokuvan historia (History of Cinema) by the mid-70s, which was the only survey of world cinema published by a Scandinavian. But you must remember this was before video. So how did I see films? I went to archives and film shows everywhere. I also had an interest in interviewing film directors. So within the first group of people that we invited to the festival, I already knew Samuel Fuller. I knew Bertrand Tavernier. I'd met the Kaurismäki Brothers with Jonathan Demme. I knew Jean-Pierre Gorin. They were all willing to come as guests to the festival. In fact, since that first festival, no one has refused to come to the Midnight Sun Film Festival. It's just too strange to refuse.

So the festival was created and one specialty of the festival started on the very first morning of the first day, which was that every day at 10:00 there would be a two-hour discussion with one of the guests. It was an astounding event for a film festival. Usually, conversations with guests are flashy and rapid; but, we dedicated time for discussion, which became a signature for the festival. Several guests have since said that it was like a psychoanalytic session. But it was not all serious. There were plenty of funny moments and lots of laughing during the festival, but basically we respected the filmmakers as serious human beings and not joke machines at press meetings. We concentrated on seeing films. And the filmmakers would have time to talk to people on the street. Many film festivals destroy themselves by isolating the big names from their public. At the Midnight Sun Film Festival we didn't even care if someone was a "big name" or not, everybody behaved, no one acted like a star. For example, when Francis Ford Coppola came in 2002, he was absolutely wonderful. He was just one of the group. He never acted as if he were important. Never questioned why he had been invited.

Practicality is one of the most important attitudes when creating a film festival. If we showed a film, we intended it to be a memorable screening under the best circumstances. We wanted to represent the original work of filmmakers in the best way possible so that it would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I remember that second year Michael Powell stated what has been frequently stated since: "It was as if I was seeing my own film for the first time." That's a specific experience the Midnight Sun Film Festival provides.

Guillén: When is the Midnight Sun Film Festival held?

Von Bagh: It's always in mid-June 12-16. The 22nd of June is the Scandanavian mid-Summer and the festival is one week before that.

Guillén: The sense I'm getting when folks speak about "destination film festivals" is that these are events precisely meant to entice cinephiles to travel far for specific programming. With regard to the Midnight Sun Film Festival, it sounds as if there's an element of the pilgrimage involved. Cinephiles travel to a festival where films will be devotedly dealt with at depth. There's a deep motivation at work.

Von Bagh: With, perhaps, one added nuance. I don't think you could call the Midnight Sun Film Festival audience a cinephilic audience. Of course they like cinema, that's why they come, but they're not as knowledgeable as cinephiles are. By contrast, Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna is a cinephilic paradise. All the leading cinephiles of the world gather there. But in Finland at the Midnight Sun Film Festival, the audience is composed more of young people who come from all parts of Finland and are curious. By being curious, and accumulating knowledge in front of our eyes, by being directly influenced by film, they are somehow the best audience you can have.

Guillén: The Bologna film festival, then, how long have you been with them? How did that opportunity come about?

Von Bagh: Quite surprisingly, at the end of 2000 I was asked by the founder and existing director of the festival Gian Luca Farinelli to take over the festival in 2001. He was feeling that he could no longer run the festival because he had been hired as the director of the cinematheque and film archive Cineteca Bologna. Cineteca Bologna and Il Cinema Ritrovato are, in effect, one and the same thing; and so Farinelli is my boss in a sense. He basically said, "You do it now." This was one of the most surprising developments of my life. I would never have imagined that I, as a foreigner, would end up being the director of one of the best film festivals in the world! I was always happy to attend and saw everything there and admired it very much. As a foreigner, there were immediately practical difficulties, including some resistance to my appointment, but not so much. It was actually through the encouragement of his colleagues at film archives in Portugal and Spain that I was offered the position. I had never done anything abroad and so, for me, I thought, "Why not do that?" I didn't for a moment think there would be any difficulty in running two film festivals. I would run a third festival if someone wanted me. I've been with Bologna for 13 years now.

Guillén: What are the dates of Il Cinema Ritrovato?

Von Bagh: It runs from the last days of June to early August, eight days.

Guillén: So these festivals are back to back?!

Von Bagh: Yes, back to back. Which has become more and more difficult for me. In the last few years there has only been one day between the Midnight Sun Film Festival and Il Cinema Ritrovato, so it's almost inhumanly possible to recover from one festival to attend the next, let alone to switch the pathways of your brain because, as festivals, they are so different from each other. As we've already discussed, one of them is for cinephiles and the other is for the highest specialists of the world where you have to talk to them and satisfy their wishes to see their films. That's one of the reasons so many people come to the Midnight Sun Film Festival because there are so many diverse programs there and many films that no one has ever seen.

Guillén: Your criticism of the current film festival landscape is how so many of them have capsized into celebrity events where the spectacular dimension of a film festival is overemphasized.

Von Bagh: Very much. Not only the celebrity but that they are dedicated to paying attention only to known names. I would guess that remarkable films escape their attention all the time. They don't access them. They don't even look at them. A thousand films come out every year and no one pays attention to the unknown filmmakers so it's possible to say that the best film of the year might not make it to such a film festival at all.

Guillén: Recently, in a conversation with Thomas Elsaesser, he explained to me that the European film festival landscape was created at the time in conscious defiance or opposition to Hollywood's hegemony and that for many years, at least a couple of decades, these European film festivals were able to advocate cinema under the aegis of national cinemas with an auteurial emphasis. But somehow that has been co-opted again by the same commercial forces that they were initially resisting.

Von Bagh: He's absolutely right. Something ghostly happened along the years. Somehow European film festivals have become more Hollywood than Hollywood itself, not only with the ceremonies which imitate Hollywood, but also the concentration on best-selling names, and attracting audiences with stars who they pay to attend.

I am ambivalent about the Cannes Film Festival. I attended Cannes three times in a row in the early '70s when it was still relatively easy to get around. Even then I didn't much like it, and I would disappear after just a few days, but then beginning in 1999 I served three times as a juror at Cannes, otherwise I wouldn't have gone. I served on the jury for Caméra d'Or, which is for first films, and the chairman was Michel Piccoli and I would say that is the best time I had at Cannes because he was such a great personality. Then I served on the FIPRESCI jury, which was the most anonymous because no one on the jury even had time to sit down to talk to each other. It was restless. Then suddenly in 2004 I received a telephone call from Thierry Fremaux inviting me to be part of the Grand Jury. What surprises me now in retrospect is that I seem to have been the only film critic or film historian in the last 20 years who has been on the Grand Jury, which shows how wrong everything is because there should always be at least one film critic or film historian on the jury. They act as if we don't have the knowledge. Instead, they invite stars who aren't knowledgeable about film. The year I was there the jury was run by Quentin Tarantino. What was clearly lacking on the jury was a knowledge of film. That's when I finished with Cannes.

What is good about Cannes is that there is a cinephilic heart behind the machinations. That means they focus on innovation and—with regard to the names—there are not just 20 names from world cinema, but 50 names from world cinema, which means that when someone like Chantal Akerman or Jean-Marie Straub or Manoel de Oliveira make a new film, Cannes will promote them by giving their film good placement. Also, the most interesting new cinema is provided necessary help by Cannes. That is the best that I can say about the Cannes Film Festival.

Guillén: It's my understanding that—in reaction to the fact that the perspective or the vision of European film culture has capsized under the weight of international commercial interests—some film festivals have consciously matured into archival film festivals. Either that or strongly enunciating within their programs restored films from the archives. As you know, here in San Francisco we have the Silent Film Festival, which has turned into one of the best in the world....

Von Bagh: It is very remarkable.

Guillén: ...and we have Noir City, which focuses on Hollywood product but with a focus on public engagement with film preservation. Il Cinema Ritrovato clearly falls within this domain.

Von Bagh: That is the whole point of that festival. There are not other attractors at all. It's totally about rare, seldom seen films that have all but disappeared, restored films and so forth. With the silent cinema, they have a multitude of films that you wouldn't see anywhere else. It's simply the best place to find remarkably interesting old films.

Guillén: It strikes me that the reason that commercial forces could co-opt cinema is because audiences have let them. Is that because, as audiences, we've been colonized by commercial desires? Have we been taught to want only so much out of cinema? And how can festival progammers generate a film festival culture that teaches audiences, and guides them, not only to deeper historical connections to cinema, but to present and relevant connections to cinema?

Von Bagh: I would simply say that film festivals are absolutely free to do better than whatever they do nowadays. They are hiding behind the mask of audience opinion. It's a pretense. First, the audience is not as stupid as they think they are. Besides, it's not about that at all. It's not about whether the audience is stupid or not. At Il Cinema Ritrovato we can freely show anything of real rarity and we will have a full house. Audiences can trust us as programmers, and for me that's the most gratifying thing to see during a festival is when the audience sees something rare.

Someone in the audience might be at their very first film festival, but will still take almost anything. The point is film festivals are a place where you can get audiences. That's somehow alarming. The film culture that ought to be—and used to be—in the network of commercial cinemas, which had repertory theaters that would show films from 20-30 years back, has disappeared completely in Finland. It's impossible for Vertigo or a Preston Sturgess or a Humphrey Bogart film to come to a local theater. It doesn't happen anymore, even though such was the case just 25 years ago. Audiences, who have come to expect mediocre films at commercial theaters, attend a film festival and—within the frame of the festival—will accept any program you're proposing. As a programmer, then you can take considerable risks. At the Midnight Sun Film Festival, all we have to do is advertise that we are showing a film that has not been screened at a commercial theater in 25 years and the house is full.

Guillén: When the European film festival culture started to thrive, the concept of the national cinema became an important tool by which to promote perhaps the most artistic endeavors from each country. However, in our contemporary moment, with production expenses for film becoming exorbitant, there's more international financing going on. That makes the definition of a national cinema slippery. Can you speak to that?

Von Bagh: It's been a problem for quite some years now. And I'm always trying to avoid the dialectic that the more national you are with a film, the more local and truthful to a particular reality, the more universal you get. There was this saying in the '60s and '70s among the Anglo-Saxon film festivals that many of these films situated themselves "mid-Atlantic", meaning their audience was indeterminate; that the films were created for abstract international audiences. This is unfortunate for world cinema because it means local films will disappear. And even remarkable filmmakers will make films that don't situate themselves anywhere.

Roman Polanski was great when he was doing Chinatown in Los Angeles, Repulsion in London, not to speak of his early Polish films. But now his films in a way seem to spread everywhere; they don't have any characteristics of film.

Guillén: You say you're trying to avoid the dialectic that the local can lead to the universal?

Von Bagh: Exactly. My own modest films are very local. For me, it's interesting to think of my youth and my school time in northern Finland. What will happen to those films? For the first time, my films move around in retrospectives in Europe and so on. What will happen to these films that are limited to my childhood, my young age, that town, and what happened there? Somehow I'm hopeful that my films will become something that everyone will understand. I didn't compromise. I didn't remove my films from their surroundings.

Guillén: The compromise taken to make something seemingly international strikes me as a colonial mindset.

Von Bagh: That is a beautiful definition. That's quite thoughtful. It is colonialization. But it's happening in the big countries as well. It's more visible and obvious in the case of some Costa Rican director, but is less obvious with a United States-based director.

Guillén: You've been a programmer for such a long time, do you see a distinction between programming and curating?

Von Bagh: I've never thought of any difference between them because I was sometimes on both sides. Every day I learn the same thing somehow. But I feel the pressure of being the head of a film festival. Once, Edith Kramer and I were having some coffee after an interview and she remembered seeing me at the festival in Bologna sitting in the movies all the time. Edith said, "That's it." That was her policy also. It's a natural instinct. How would you know what's happening in the audience if you don't sit and watch films with them? Then you know your next step after that. I'm always sitting with the audience. That's my way to present. I mentioned this a little earlier, but you can articulate a film showing in a film festival in a way that the screening can be as memorable as a live performance of music or theater.

Guillén: As someone who has seen film culture evolve over the past few decades, any thoughts on the so-called digital revolution?

Von Bagh: I'm extremely pessimistic about that. No one would listen to my complaints. I refuse to see a film like Sunset Boulevard or Singing in the Rain on digital. For me, when it loses its own material truth, it's not the same thing anymore. I think it's tragic.

"Peter von Bagh embodies the essence of the Mel Novikoff Award," said Rachel Rosen, San Francisco Film Society's director of programming. "He has worked indefatigably and infectiously to share his appreciation of world cinema and has many good stories to share about the filmmakers and icons he's met during his half century in the movies."

Throughout his career Peter von Bagh wore many different hats in the cinematic arena. Besides being a film director, one especially attracted to compilation films, von Bagh had been a television and radio producer, book publisher, curator and program director of the Finnish Film Archive, professor of film history, artistic director and cofounder of the Midnight Sun Film Festival and artistic director of Bologna's Il Cinema Ritrovato festival. As a film critic and historian, he (co)wrote and/or (co)edited more than 30 books, including The History of World Cinema, 1975 and 1998. Regarded as a Finnish national treasure, von Bagh is a true master of international film and an extraordinary example of cinema lived to the fullest.

With both SFIFF56 screenings of Helsinki, Forever and Eight Deadly Shots, I was keenly aware of something von Bagh articulated in his documentary Sodankylä Forever (Finland, 2010-2011): "Film screenings, like films themselves, are part of history; the seismograph of the era." With his passing earlier this week, I recall the privilege of speaking with von Bagh when he was in San Francisco in 2013 to receive the Mel Novikoff Award. He was unpretentious and generous with his intellect and gifted me the four-DVD set of Sodankylä Forever; one of the treasures in my library. My thanks go out to Bill Proctor of the San Francisco Film Society for facilitating our conversation.

* * *

Michael Guillén: First and foremost, congratulations on receiving the Mel Novikoff Award from the San Francisco Film Society.

Peter von Bagh: Thank you.

Guillén: One of my predominant interests is in film festival culture and I thought you would be the perfect person to talk to about that.

Von Bagh: That's okay, but with the strong limitation that I don't go to film festivals. I don't like them, though I run a couple of them.

Guillén: Let's talk a bit about the two festivals you run. Can you synopsize for me their singular focus? How long you've been working with each? And how you were drawn into running them when, as you confess, you don't like film festivals?

Von Bagh: In Finland it was more natural in a way because I was programming for the Finnish Film Archive [the National Audiovisual Institute of Finland] for 20 years or so. I started there in 1967 and was programming there all the time until the mid-80s. Originally, I was the Executive Director of the Archive but then I concentrated on programming because I felt that was my thing—I didn't want to go to meetings or anything—so I had that background.

Then I finished at the Finnish Film Archive in 1985, which was very sad for me. I was programming even in my dreams and had no outlets for my thoughts. But that same year Anssi Mänttäri, a Finnish director, was in a small village in the north out in the middle of nowhere—I don't know why—and it was November and all dark. Anssi was probably drunk and was looking out the window at ... nothing. Even during the daytime there were no people around, just emptiness. Then he came up with the idea: "Why not start an international film festival here?" Certainly, the most absurd of all origins for a festival. He was associated with two emerging talents of the time, Mika and Aki Kaurismäki, there were the three of them, and Anssi contacted me and asked me if I would like to become the director of the festival? That's how the Midnight Sun Film Festival started.

At first, I doubted the idea could work. I felt it was too absurd to travel so far for a film festival. But within a month I agreed to do it. We already had good contacts. I had been around for a while with the Archive and had already published Elokuvan historia (History of Cinema) by the mid-70s, which was the only survey of world cinema published by a Scandinavian. But you must remember this was before video. So how did I see films? I went to archives and film shows everywhere. I also had an interest in interviewing film directors. So within the first group of people that we invited to the festival, I already knew Samuel Fuller. I knew Bertrand Tavernier. I'd met the Kaurismäki Brothers with Jonathan Demme. I knew Jean-Pierre Gorin. They were all willing to come as guests to the festival. In fact, since that first festival, no one has refused to come to the Midnight Sun Film Festival. It's just too strange to refuse.

So the festival was created and one specialty of the festival started on the very first morning of the first day, which was that every day at 10:00 there would be a two-hour discussion with one of the guests. It was an astounding event for a film festival. Usually, conversations with guests are flashy and rapid; but, we dedicated time for discussion, which became a signature for the festival. Several guests have since said that it was like a psychoanalytic session. But it was not all serious. There were plenty of funny moments and lots of laughing during the festival, but basically we respected the filmmakers as serious human beings and not joke machines at press meetings. We concentrated on seeing films. And the filmmakers would have time to talk to people on the street. Many film festivals destroy themselves by isolating the big names from their public. At the Midnight Sun Film Festival we didn't even care if someone was a "big name" or not, everybody behaved, no one acted like a star. For example, when Francis Ford Coppola came in 2002, he was absolutely wonderful. He was just one of the group. He never acted as if he were important. Never questioned why he had been invited.

Practicality is one of the most important attitudes when creating a film festival. If we showed a film, we intended it to be a memorable screening under the best circumstances. We wanted to represent the original work of filmmakers in the best way possible so that it would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I remember that second year Michael Powell stated what has been frequently stated since: "It was as if I was seeing my own film for the first time." That's a specific experience the Midnight Sun Film Festival provides.

Guillén: When is the Midnight Sun Film Festival held?

Von Bagh: It's always in mid-June 12-16. The 22nd of June is the Scandanavian mid-Summer and the festival is one week before that.

Guillén: The sense I'm getting when folks speak about "destination film festivals" is that these are events precisely meant to entice cinephiles to travel far for specific programming. With regard to the Midnight Sun Film Festival, it sounds as if there's an element of the pilgrimage involved. Cinephiles travel to a festival where films will be devotedly dealt with at depth. There's a deep motivation at work.

Von Bagh: With, perhaps, one added nuance. I don't think you could call the Midnight Sun Film Festival audience a cinephilic audience. Of course they like cinema, that's why they come, but they're not as knowledgeable as cinephiles are. By contrast, Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna is a cinephilic paradise. All the leading cinephiles of the world gather there. But in Finland at the Midnight Sun Film Festival, the audience is composed more of young people who come from all parts of Finland and are curious. By being curious, and accumulating knowledge in front of our eyes, by being directly influenced by film, they are somehow the best audience you can have.

Guillén: The Bologna film festival, then, how long have you been with them? How did that opportunity come about?

Von Bagh: Quite surprisingly, at the end of 2000 I was asked by the founder and existing director of the festival Gian Luca Farinelli to take over the festival in 2001. He was feeling that he could no longer run the festival because he had been hired as the director of the cinematheque and film archive Cineteca Bologna. Cineteca Bologna and Il Cinema Ritrovato are, in effect, one and the same thing; and so Farinelli is my boss in a sense. He basically said, "You do it now." This was one of the most surprising developments of my life. I would never have imagined that I, as a foreigner, would end up being the director of one of the best film festivals in the world! I was always happy to attend and saw everything there and admired it very much. As a foreigner, there were immediately practical difficulties, including some resistance to my appointment, but not so much. It was actually through the encouragement of his colleagues at film archives in Portugal and Spain that I was offered the position. I had never done anything abroad and so, for me, I thought, "Why not do that?" I didn't for a moment think there would be any difficulty in running two film festivals. I would run a third festival if someone wanted me. I've been with Bologna for 13 years now.

Guillén: What are the dates of Il Cinema Ritrovato?

Von Bagh: It runs from the last days of June to early August, eight days.

Guillén: So these festivals are back to back?!

Von Bagh: Yes, back to back. Which has become more and more difficult for me. In the last few years there has only been one day between the Midnight Sun Film Festival and Il Cinema Ritrovato, so it's almost inhumanly possible to recover from one festival to attend the next, let alone to switch the pathways of your brain because, as festivals, they are so different from each other. As we've already discussed, one of them is for cinephiles and the other is for the highest specialists of the world where you have to talk to them and satisfy their wishes to see their films. That's one of the reasons so many people come to the Midnight Sun Film Festival because there are so many diverse programs there and many films that no one has ever seen.

Guillén: Your criticism of the current film festival landscape is how so many of them have capsized into celebrity events where the spectacular dimension of a film festival is overemphasized.

Von Bagh: Very much. Not only the celebrity but that they are dedicated to paying attention only to known names. I would guess that remarkable films escape their attention all the time. They don't access them. They don't even look at them. A thousand films come out every year and no one pays attention to the unknown filmmakers so it's possible to say that the best film of the year might not make it to such a film festival at all.

Guillén: Recently, in a conversation with Thomas Elsaesser, he explained to me that the European film festival landscape was created at the time in conscious defiance or opposition to Hollywood's hegemony and that for many years, at least a couple of decades, these European film festivals were able to advocate cinema under the aegis of national cinemas with an auteurial emphasis. But somehow that has been co-opted again by the same commercial forces that they were initially resisting.

Von Bagh: He's absolutely right. Something ghostly happened along the years. Somehow European film festivals have become more Hollywood than Hollywood itself, not only with the ceremonies which imitate Hollywood, but also the concentration on best-selling names, and attracting audiences with stars who they pay to attend.

I am ambivalent about the Cannes Film Festival. I attended Cannes three times in a row in the early '70s when it was still relatively easy to get around. Even then I didn't much like it, and I would disappear after just a few days, but then beginning in 1999 I served three times as a juror at Cannes, otherwise I wouldn't have gone. I served on the jury for Caméra d'Or, which is for first films, and the chairman was Michel Piccoli and I would say that is the best time I had at Cannes because he was such a great personality. Then I served on the FIPRESCI jury, which was the most anonymous because no one on the jury even had time to sit down to talk to each other. It was restless. Then suddenly in 2004 I received a telephone call from Thierry Fremaux inviting me to be part of the Grand Jury. What surprises me now in retrospect is that I seem to have been the only film critic or film historian in the last 20 years who has been on the Grand Jury, which shows how wrong everything is because there should always be at least one film critic or film historian on the jury. They act as if we don't have the knowledge. Instead, they invite stars who aren't knowledgeable about film. The year I was there the jury was run by Quentin Tarantino. What was clearly lacking on the jury was a knowledge of film. That's when I finished with Cannes.

What is good about Cannes is that there is a cinephilic heart behind the machinations. That means they focus on innovation and—with regard to the names—there are not just 20 names from world cinema, but 50 names from world cinema, which means that when someone like Chantal Akerman or Jean-Marie Straub or Manoel de Oliveira make a new film, Cannes will promote them by giving their film good placement. Also, the most interesting new cinema is provided necessary help by Cannes. That is the best that I can say about the Cannes Film Festival.

Guillén: It's my understanding that—in reaction to the fact that the perspective or the vision of European film culture has capsized under the weight of international commercial interests—some film festivals have consciously matured into archival film festivals. Either that or strongly enunciating within their programs restored films from the archives. As you know, here in San Francisco we have the Silent Film Festival, which has turned into one of the best in the world....

Von Bagh: It is very remarkable.

Guillén: ...and we have Noir City, which focuses on Hollywood product but with a focus on public engagement with film preservation. Il Cinema Ritrovato clearly falls within this domain.

Von Bagh: That is the whole point of that festival. There are not other attractors at all. It's totally about rare, seldom seen films that have all but disappeared, restored films and so forth. With the silent cinema, they have a multitude of films that you wouldn't see anywhere else. It's simply the best place to find remarkably interesting old films.

Guillén: It strikes me that the reason that commercial forces could co-opt cinema is because audiences have let them. Is that because, as audiences, we've been colonized by commercial desires? Have we been taught to want only so much out of cinema? And how can festival progammers generate a film festival culture that teaches audiences, and guides them, not only to deeper historical connections to cinema, but to present and relevant connections to cinema?

Von Bagh: I would simply say that film festivals are absolutely free to do better than whatever they do nowadays. They are hiding behind the mask of audience opinion. It's a pretense. First, the audience is not as stupid as they think they are. Besides, it's not about that at all. It's not about whether the audience is stupid or not. At Il Cinema Ritrovato we can freely show anything of real rarity and we will have a full house. Audiences can trust us as programmers, and for me that's the most gratifying thing to see during a festival is when the audience sees something rare.

Someone in the audience might be at their very first film festival, but will still take almost anything. The point is film festivals are a place where you can get audiences. That's somehow alarming. The film culture that ought to be—and used to be—in the network of commercial cinemas, which had repertory theaters that would show films from 20-30 years back, has disappeared completely in Finland. It's impossible for Vertigo or a Preston Sturgess or a Humphrey Bogart film to come to a local theater. It doesn't happen anymore, even though such was the case just 25 years ago. Audiences, who have come to expect mediocre films at commercial theaters, attend a film festival and—within the frame of the festival—will accept any program you're proposing. As a programmer, then you can take considerable risks. At the Midnight Sun Film Festival, all we have to do is advertise that we are showing a film that has not been screened at a commercial theater in 25 years and the house is full.

Guillén: When the European film festival culture started to thrive, the concept of the national cinema became an important tool by which to promote perhaps the most artistic endeavors from each country. However, in our contemporary moment, with production expenses for film becoming exorbitant, there's more international financing going on. That makes the definition of a national cinema slippery. Can you speak to that?

Von Bagh: It's been a problem for quite some years now. And I'm always trying to avoid the dialectic that the more national you are with a film, the more local and truthful to a particular reality, the more universal you get. There was this saying in the '60s and '70s among the Anglo-Saxon film festivals that many of these films situated themselves "mid-Atlantic", meaning their audience was indeterminate; that the films were created for abstract international audiences. This is unfortunate for world cinema because it means local films will disappear. And even remarkable filmmakers will make films that don't situate themselves anywhere.

Roman Polanski was great when he was doing Chinatown in Los Angeles, Repulsion in London, not to speak of his early Polish films. But now his films in a way seem to spread everywhere; they don't have any characteristics of film.

Guillén: You say you're trying to avoid the dialectic that the local can lead to the universal?

Von Bagh: Exactly. My own modest films are very local. For me, it's interesting to think of my youth and my school time in northern Finland. What will happen to those films? For the first time, my films move around in retrospectives in Europe and so on. What will happen to these films that are limited to my childhood, my young age, that town, and what happened there? Somehow I'm hopeful that my films will become something that everyone will understand. I didn't compromise. I didn't remove my films from their surroundings.

Guillén: The compromise taken to make something seemingly international strikes me as a colonial mindset.

Von Bagh: That is a beautiful definition. That's quite thoughtful. It is colonialization. But it's happening in the big countries as well. It's more visible and obvious in the case of some Costa Rican director, but is less obvious with a United States-based director.

Guillén: You've been a programmer for such a long time, do you see a distinction between programming and curating?

Von Bagh: I've never thought of any difference between them because I was sometimes on both sides. Every day I learn the same thing somehow. But I feel the pressure of being the head of a film festival. Once, Edith Kramer and I were having some coffee after an interview and she remembered seeing me at the festival in Bologna sitting in the movies all the time. Edith said, "That's it." That was her policy also. It's a natural instinct. How would you know what's happening in the audience if you don't sit and watch films with them? Then you know your next step after that. I'm always sitting with the audience. That's my way to present. I mentioned this a little earlier, but you can articulate a film showing in a film festival in a way that the screening can be as memorable as a live performance of music or theater.

Guillén: As someone who has seen film culture evolve over the past few decades, any thoughts on the so-called digital revolution?

Von Bagh: I'm extremely pessimistic about that. No one would listen to my complaints. I refuse to see a film like Sunset Boulevard or Singing in the Rain on digital. For me, when it loses its own material truth, it's not the same thing anymore. I think it's tragic.

BOOK EXCERPT—HUCKLEBERRY: Stories, Secrets, and Recipes From Our Kitchen

"Everything in generosity" is the motto of Zoe Nathan, the big-hearted baker behind Santa Monica's favorite neighborhood bakery and breakfast spot, Huckleberry Bakery & Café. This irresistible cookbook collects more than 115 recipes and more than 150 color photographs, including how-to sequences for mastering basics such as flaky dough and lining a cake pan. Huckleberry's recipes span from sweet (rustic cakes, muffins, and scones) to savory (hot cereals, biscuits, and quiche). True to the healthful spirit of Los Angeles, these recipes feature whole-grain flours, sesame and flax seeds, fresh fruits and vegetables, natural sugars, and gluten-free and vegan options—and they always lead with deliciousness. For bakers and all-day brunchers, Huckleberry will become the cookbook to reach for whenever the craving for big flavor strikes.

Reprinted with permission from Huckleberry: Stories, Secrets and Recipes From Our Kitchen by Zoe Nathan (with Josh Loeb and Laurel Almerinda), © 2014. Published by Chronicle Books. Photography © 2014 by Matt Armendariz. Support your local independent bookstore, or purchase Huckleberry at IndieBound or Amazon.

The Evening Class has chosen the following three recipes to share with our readership.

Brown Rice Quinoa Pancakes

(Makes about 15 pancakes)

Occasionally I make something I love so much that I literally want to eat it every day, and that's how I feel about these. I like them as straightforward pancakes cooked on a griddle, but they're also really good as a large baked pancake. Pour all the batter into a buttered cast-iron skillet, bake at 450°F / 230°C for about 15 minutes, and serve immediately straight from the skillet slathered with butter and maple syrup. It's a fun way to eat a pancake with a group. These should be your go-to breakfast anytime you have leftover rice. And if you're not up for cooking quinoa, you can always use all brown rice, but I will say if you choose to use just quinoa, the flavor can be a little overpowering. It is mandatory to serve these with maple syrup, but, honestly, you don't even need butter these pancakes are so good.

½ cup/60 g whole-wheat flour

5 tbsp/50 g cornmeal

2 tbsp rolled oats

1 tbsp flax seed meal or wheat germ

2 tsp chia seeds or poppy seeds

1 tbsp millet

2 tbsp brown sugar

1½ tsp baking soda

1 tsp kosher salt

2 cups/480 ml buttermilk

½ cup/110 g unsalted butter, melted

3 eggs

1¼ cups/200 g cooked brown or wild rice

½ cup/100 g cooked quinoa

1. Put the whole-wheat flour, cornmeal, rolled oats, flax seed meal, chia seeds, millet, brown sugar, baking soda, and salt in a large bowl. Add the buttermilk, melted butter, and eggs and whisk to combine. Stir in the rice and quinoa.

2. About 5 minutes before you're ready to make the pancakes, pre-heat a greased griddle or large skillet over medium-high heat; the griddle is ready when a few droplets of water sizzle and dance across the surface. But once heated, lower the heat to medium to prevent burning.

3. Drop ⅓ cup/80 ml of batter onto the hot griddle. When bubbles set on the surface of the pancake and the bottom is golden, flip and cook for about 1 minute longer. Serve immediately, while hot.

These are best the moment they leave the griddle.

Bacon Cheddar Muffins

(Makes 15 muffins)

Please play with this recipe. Add and subtract to your heart's content. Don't eat meat? Add additional cheese and herbs for super-cheesy herby muffins. No rye flour in the pantry? Substitute another flour, like whole-wheat, buckwheat, or, if you must, more all-purpose flour. Black pepper is not my thing but Laurel is obsessed. She always adds a healthy dose to these. Ham instead of bacon? Do it. Goat cheese? Why not? Like I said, play!

Browning the tops of these before they overbake inside is the key to success. So you may want to bake one muffin pan at a time, right at the top of your oven. Feel free to ride your oven dial and go hotter or cooler to control the browning, but just remember that color is flavor, so you want these pretty dark.

6 tbsp/85 g unsalted butter, cubed, at room temperature

2 tbsp sugar

1½ tsp kosher salt

3 eggs

¾ cup/100 g all-purpose flour

¾ cup/120 g cornmeal

6 tbsp/40 g rye flour

1½ tbsp baking powder

½ cup + 1 tbsp/135 ml canola oil

3 tbsp + 2 tsp/55 ml maple syrup

1 cup + 2 tbsp/175 ml buttermilk

½ cup/70 g diced Cheddar (cut into 1-in/2.5-cm cubes), plus ¼ cup/30 g grated Cheddar

6 tbsp/40 g grated Parmesan

11 slices cooked bacon, coarsely chopped, plus 1½ tbsp bacon fat, cooled

¼ cup/10 g fresh chives, parsley, or a combo, finely chopped

Chopped rosemary for garnishing

1. Position a rack near the top of your oven and preheat to 400°F/ 200°C. Line two 12-cup muffin pans with 15 paper liners, spacing them evenly between the two pans.

2. In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and salt for 1 to 2 minutes until nice and fluffy. Incorporate the eggs slowly, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Add the all-purpose flour, cornmeal, rye flour, and baking powder and mix until incorporated. Add the canola oil, maple syrup, and buttermilk. Scrape the mixer bowl well, making sure everything is well incorporated. Add the diced Cheddar, 4 tbsp/25 g of the Parmesan, the bacon, and chives. Mix just until dispersed, folding by hand to be sure.

3. Fill the muffin cups to the very top.

4. In a small bowl toss the grated Cheddar with the remaining 2 tbsp Parmesan and sprinkle evenly over the muffins. Bake for about 15 minutes, until nicely browned but not overbaked inside. Garnish with chopped rosemary.

5. These are best eaten the day they're made.

Fresh Corn Cornbread

(Makes sixteen 2-in/5-cm squares)

This is your old-fashioned cornbread made insanely moist and delicious. It is the opposite of dry, and can really stand on its own without needing to be slathered with butter. This recipe is wildly versatile. Use fresh corn if you can; if it's not in season, you don't need it. For a fun jalapeño Cheddar version, increase the salt to 2 tsp, omit the honey, add ½ cup/120 g grated Cheddar, 2 jalapeños, finely chopped, and 2 tbsp chopped parsley. Take it any direction you please. The honey glaze is optional; if you go in a more savory direction, I would omit it. If you are making this cornbread for use in our Cornbread Pudding (page 164), omit the fresh corn and reduce the sugar to 6 tbsp/60 g.

6 tbsp/85 g unsalted butter

½ cup + 1 tbsp/110 g sugar

1¾ tsp kosher salt

4 eggs

1 cup/160 g cornmeal

¾ cup + 2 tbsp/100 g all-purpose flour

¼ cup/30 g whole-wheat flour

1 tbsp + 1 tsp baking powder

½ cup/120 ml whole milk

1 cup/240 ml buttermilk

¾ cup/180 ml canola oil

2 tbsp honey, plus ¼ cup/85 g for glazing (optional)

1½ cups/365 g fresh corn kernels (about 2 cobs; optional)

1. Preheat your oven to 350°F/180°C and grease an 8-by-8-in/20-by-20 cm pan.

2. In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and salt on medium-high speed until light and fluffy, about 2 minutes. Incorporate the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Be sure to scrape the sides of the bowl well. Pause mixing and add the cornmeal, all-purpose flour, whole-wheat flour, and baking powder.

3. With the mixer on low speed, pour in the milk, buttermilk, canola oil, and 2 tbsp honey and mix. This is a very loose batter. Small lumps of butter are no problem, but avoid any lumps of flour. If you see them, mix a little longer or work them out with your fingers.

4. Fold in the corn, if in season; if not, omit.

5. Pour the batter into the prepared pan and bake for 45 to 50 minutes, or until a cake tester comes out clean. Do not overbake!

6. If you are choosing to glaze, slightly warm the ¼ cup/85 g honey in a small saucepan and lightly brush the top of the warm cake. This is best served the day it's made but keeps, wrapped well, at room temperature, for up to 2 days.

Zoe Nathan and Josh Loeb are the wife-and-husband team who own and operate Huckleberry Bakery & Café. They fell in love while working together at their nearby restaurant Rustic Canyon Wine Bar and Seasonal Kitchen; they also own and operate Milo & Olive and Sweet Rose Creamery. They live with their two awesome kids in Santa Monica, California.

Laurel Almerinda has worked side by side with Zoe for years at Huckleberry, and now runs day-to-day pastry operations. Together Laurel and Zoe have created countless items, learned from each other, and grown in ways they never could have imagined. Laurel lives in Venice, California, with her husband, Ethan Pines.

Matt Armendariz is a celebrated food and lifestyle photographer based in Los Angeles, California.

Reprinted with permission from Huckleberry: Stories, Secrets and Recipes From Our Kitchen by Zoe Nathan (with Josh Loeb and Laurel Almerinda), © 2014. Published by Chronicle Books. Photography © 2014 by Matt Armendariz. Support your local independent bookstore, or purchase Huckleberry at IndieBound or Amazon.

The Evening Class has chosen the following three recipes to share with our readership.

Brown Rice Quinoa Pancakes

(Makes about 15 pancakes)

Occasionally I make something I love so much that I literally want to eat it every day, and that's how I feel about these. I like them as straightforward pancakes cooked on a griddle, but they're also really good as a large baked pancake. Pour all the batter into a buttered cast-iron skillet, bake at 450°F / 230°C for about 15 minutes, and serve immediately straight from the skillet slathered with butter and maple syrup. It's a fun way to eat a pancake with a group. These should be your go-to breakfast anytime you have leftover rice. And if you're not up for cooking quinoa, you can always use all brown rice, but I will say if you choose to use just quinoa, the flavor can be a little overpowering. It is mandatory to serve these with maple syrup, but, honestly, you don't even need butter these pancakes are so good.

½ cup/60 g whole-wheat flour

5 tbsp/50 g cornmeal

2 tbsp rolled oats

1 tbsp flax seed meal or wheat germ

2 tsp chia seeds or poppy seeds

1 tbsp millet

2 tbsp brown sugar

1½ tsp baking soda

1 tsp kosher salt

2 cups/480 ml buttermilk

½ cup/110 g unsalted butter, melted

3 eggs

1¼ cups/200 g cooked brown or wild rice

½ cup/100 g cooked quinoa

1. Put the whole-wheat flour, cornmeal, rolled oats, flax seed meal, chia seeds, millet, brown sugar, baking soda, and salt in a large bowl. Add the buttermilk, melted butter, and eggs and whisk to combine. Stir in the rice and quinoa.

2. About 5 minutes before you're ready to make the pancakes, pre-heat a greased griddle or large skillet over medium-high heat; the griddle is ready when a few droplets of water sizzle and dance across the surface. But once heated, lower the heat to medium to prevent burning.

3. Drop ⅓ cup/80 ml of batter onto the hot griddle. When bubbles set on the surface of the pancake and the bottom is golden, flip and cook for about 1 minute longer. Serve immediately, while hot.

These are best the moment they leave the griddle.

Bacon Cheddar Muffins

(Makes 15 muffins)

Please play with this recipe. Add and subtract to your heart's content. Don't eat meat? Add additional cheese and herbs for super-cheesy herby muffins. No rye flour in the pantry? Substitute another flour, like whole-wheat, buckwheat, or, if you must, more all-purpose flour. Black pepper is not my thing but Laurel is obsessed. She always adds a healthy dose to these. Ham instead of bacon? Do it. Goat cheese? Why not? Like I said, play!

Browning the tops of these before they overbake inside is the key to success. So you may want to bake one muffin pan at a time, right at the top of your oven. Feel free to ride your oven dial and go hotter or cooler to control the browning, but just remember that color is flavor, so you want these pretty dark.

6 tbsp/85 g unsalted butter, cubed, at room temperature

2 tbsp sugar

1½ tsp kosher salt

3 eggs

¾ cup/100 g all-purpose flour

¾ cup/120 g cornmeal

6 tbsp/40 g rye flour

1½ tbsp baking powder

½ cup + 1 tbsp/135 ml canola oil

3 tbsp + 2 tsp/55 ml maple syrup

1 cup + 2 tbsp/175 ml buttermilk

½ cup/70 g diced Cheddar (cut into 1-in/2.5-cm cubes), plus ¼ cup/30 g grated Cheddar

6 tbsp/40 g grated Parmesan

11 slices cooked bacon, coarsely chopped, plus 1½ tbsp bacon fat, cooled

¼ cup/10 g fresh chives, parsley, or a combo, finely chopped

Chopped rosemary for garnishing

1. Position a rack near the top of your oven and preheat to 400°F/ 200°C. Line two 12-cup muffin pans with 15 paper liners, spacing them evenly between the two pans.

2. In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and salt for 1 to 2 minutes until nice and fluffy. Incorporate the eggs slowly, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Add the all-purpose flour, cornmeal, rye flour, and baking powder and mix until incorporated. Add the canola oil, maple syrup, and buttermilk. Scrape the mixer bowl well, making sure everything is well incorporated. Add the diced Cheddar, 4 tbsp/25 g of the Parmesan, the bacon, and chives. Mix just until dispersed, folding by hand to be sure.

3. Fill the muffin cups to the very top.

4. In a small bowl toss the grated Cheddar with the remaining 2 tbsp Parmesan and sprinkle evenly over the muffins. Bake for about 15 minutes, until nicely browned but not overbaked inside. Garnish with chopped rosemary.

5. These are best eaten the day they're made.

Fresh Corn Cornbread

(Makes sixteen 2-in/5-cm squares)

This is your old-fashioned cornbread made insanely moist and delicious. It is the opposite of dry, and can really stand on its own without needing to be slathered with butter. This recipe is wildly versatile. Use fresh corn if you can; if it's not in season, you don't need it. For a fun jalapeño Cheddar version, increase the salt to 2 tsp, omit the honey, add ½ cup/120 g grated Cheddar, 2 jalapeños, finely chopped, and 2 tbsp chopped parsley. Take it any direction you please. The honey glaze is optional; if you go in a more savory direction, I would omit it. If you are making this cornbread for use in our Cornbread Pudding (page 164), omit the fresh corn and reduce the sugar to 6 tbsp/60 g.

6 tbsp/85 g unsalted butter

½ cup + 1 tbsp/110 g sugar

1¾ tsp kosher salt

4 eggs

1 cup/160 g cornmeal

¾ cup + 2 tbsp/100 g all-purpose flour

¼ cup/30 g whole-wheat flour

1 tbsp + 1 tsp baking powder

½ cup/120 ml whole milk

1 cup/240 ml buttermilk

¾ cup/180 ml canola oil

2 tbsp honey, plus ¼ cup/85 g for glazing (optional)

1½ cups/365 g fresh corn kernels (about 2 cobs; optional)

1. Preheat your oven to 350°F/180°C and grease an 8-by-8-in/20-by-20 cm pan.

2. In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and salt on medium-high speed until light and fluffy, about 2 minutes. Incorporate the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Be sure to scrape the sides of the bowl well. Pause mixing and add the cornmeal, all-purpose flour, whole-wheat flour, and baking powder.

3. With the mixer on low speed, pour in the milk, buttermilk, canola oil, and 2 tbsp honey and mix. This is a very loose batter. Small lumps of butter are no problem, but avoid any lumps of flour. If you see them, mix a little longer or work them out with your fingers.

4. Fold in the corn, if in season; if not, omit.

5. Pour the batter into the prepared pan and bake for 45 to 50 minutes, or until a cake tester comes out clean. Do not overbake!

6. If you are choosing to glaze, slightly warm the ¼ cup/85 g honey in a small saucepan and lightly brush the top of the warm cake. This is best served the day it's made but keeps, wrapped well, at room temperature, for up to 2 days.

Zoe Nathan and Josh Loeb are the wife-and-husband team who own and operate Huckleberry Bakery & Café. They fell in love while working together at their nearby restaurant Rustic Canyon Wine Bar and Seasonal Kitchen; they also own and operate Milo & Olive and Sweet Rose Creamery. They live with their two awesome kids in Santa Monica, California.

Laurel Almerinda has worked side by side with Zoe for years at Huckleberry, and now runs day-to-day pastry operations. Together Laurel and Zoe have created countless items, learned from each other, and grown in ways they never could have imagined. Laurel lives in Venice, California, with her husband, Ethan Pines.

Matt Armendariz is a celebrated food and lifestyle photographer based in Los Angeles, California.

Friday, September 19, 2014

ON THE WIRE: The Evening Class Interview With Linda Williams

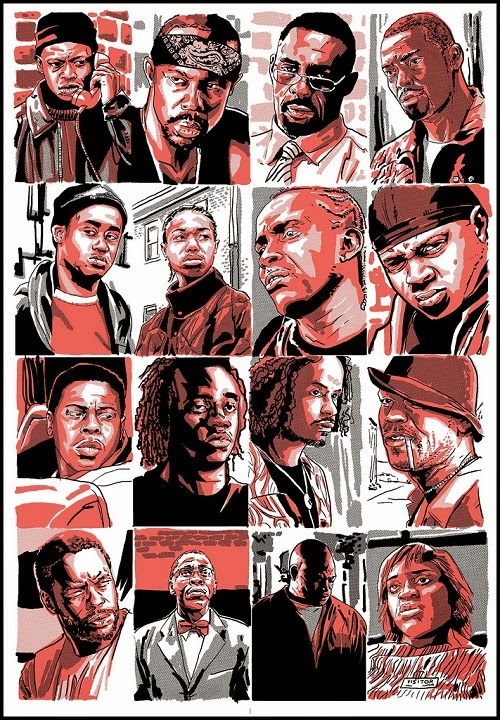

From the back cover of On The Wire (Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2014): "Many television critics, legions of fans, even the president of the United States, have cited The Wire as the best television series ever. In this sophisticated examination of the HBO serial drama that aired from 2002 until 2008, Linda Williams, a leading film scholar and authority on the interplay between film, melodrama, and issues of race, suggests what exactly it is that makes The Wire so good. She argues that while the series is a powerful exploration of urban dysfunction and institutional failure, its narrative power derives from its genre. The Wire is popular melodrama, not Greek tragedy, as critics and the series creator David Simon have claimed. Entertaining, addictive, funny, and despairing all at once, it is a serial melodrama grounded in observation of Baltimore's people and institutions: of cops and criminals, schools and blue-collar labor, local government and local journalism. The Wire transforms close observation into an unparalleled melodrama by juxtaposing the good and evil of individuals with the good and evil of institutions."

Linda Williams is Professor of Film Studies and Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. Her books include Screening Sex and Porn Studies, both also published by Duke University Press; Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson; Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film; and Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the "Frenzy of the Visible." In 2013, Williams received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Linda Williams' introduction to On The Wire is used with permission of Duke University Press. Purchase On The Wire by supporting your local bookstore, or buy the book through Amazon.com. My thanks to Laura Sell at Duke University Press for setting up my interview with Linda Williams.

Michael Guillén: In your introduction to On The Wire, you explain that you got into watching The Wire when you were laid up in bed in the summer and fall of 2007. How did you then go about structuring your study? Did you watch the series several times? How did you decide which episodes would best present your themes?

Linda Williams: It was harder than anything I'd ever done because we're talking about more than 60 hours of viewing time. I found that daunting. I simply watched The Wire the way anybody watches it, though I didn't watch it on a weekly basis—somebody had given me what were in effect bootleg copies of the first three seasons—so I was able to watch it every night and I did. It was the wonderful thing that I would give myself every night. I would go to bed at 7:00 and I would watch an hour of The Wire and then go to sleep exhausted.

It was overwhelming to me and also really intriguing: what was it that I had watched? What would I call it? A really long movie? That didn't quite seem right. I'd never encountered a serial that was as compelling. Serials never seemed timely to me, even though I'd grown up with serials like Flash Gordon.