Setting and mindset—LSD research theorist

Stanislav Grof argued over the years—were essential for maximizing that drug's healing potential. The same might be said about cinema's power to ameliorate grief. My beloved sister Barbara Guillén passed away no less than three days before opening night of the 57th edition of the

San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF) after a prolonged hospitalization and—though I had some reservations about attending SFIFF as a consequence—concluded it would be best to continue with my scheduled participation. It was the appropriate thing to do, if at times admittedly difficult. Friends and colleagues have offered respectful condolences and loving support, helping to shoulder my burden, and I've taken comfort in the familiarity of the festival's infrastructure, its venues—the Castro Theatre, the Sundance Kabuki, and New People Cinema—in whose auditoriums I have automatically settled into favorite seats determined over years of attendance. Left side, center aisle.

Safe and secure in my setting, my mindset—on the other hand—has been volatile, a wild card, and I throw that out there to qualify how grief can affect reception and perspective on a film. Stories of children in peril, death watch sequences, testimonials of social injustice, have always been problematic for me to handle emotionally, but even more so this go-round. Exhaustion and rogue waves of overwhelming sorrow have weakened my patience for long takes, slapstick gags, and indie narratives that seem slight, even unnecessary. That being said, I am convinced more than ever that films are never seen in a vacuum; that our subjectivities—however affected by the crises in our lives—influence how we perceive and interpret the frenzy on the wall, which is in essence the symbiotic thrill of the cinephilic experience. That's not meant to be an apology for how I have reacted to the films I've seen in my first week at the festival, but merely a statement of cinematic fact. Offered with a note of gratitude at how cinema has helped me steer—yet again—through a tumultuous period of my life. I dedicate this year's coverage to my dear sister Barbara.

Unable to negotiate opening night, my opening pitch for SFIFF was Pittsburgh Pirate

Dock Ellis's infamous 1970 no-hitter on LSD, the obvious hook to

Jeff Radice's

No No: A Dockumentary (2014) [

official site] which Radice expands upon to assemble a fascinating, rich documentary about the baseball player nicknamed "the Muhammad Ali of the ballpark." St. Augustine in all his late life contrition could have played shortstop to this tale of a man who was proudly black, loudly opinionated, addicted to drugs and alcohol, but who—in his later years—discovered the value of remorse and turned his life around to counsel other athletes battling demons with which he was all too familiar. I'm not a sports enthusiast by nature, but am certainly enthused over Radice's sports doc, which reaches past the diamond to reveal the social pressures of a time and place on a beloved American sport and its players. An added high-five to the film's funky psychedelic score by

Adam Horovitz (of the Beastie Boys). Further thanks to Alex Hecht for forwarding the url to No Mas and artist James Blagden's animated rendition of Dock Ellis' legendary LSD no-hitter.

Speaking of high fives,

Mike Jacobs' captivating 10-minute short

The High Five (2014) preceded

No No: A Dockumentary. They're perfect teammates. On October 2, 1977,

Dusty Baker hit his 30th homerun of the season, making history as the 4th player on the Dodgers to hit 30 or more home runs. As Baker rounded the bases, an excited rookie named

Glenn Burke met him at home plate, raised his arm high in the air and slapped Baker five. It was the first high five recorded in the history of sports. A year later, Burke was forced out of baseball amid rumors of his sexual orientation. The film takes audiences back to the spontaneous moment between the two men and tells the story of how the celebratory gesture spread throughout the sports world at the same time Burke was being forced from the game he loved. Again, though not necessarily a sports enthusiast, I am highly respectful of this reclaimed gem of gay history. It

sparkles.

Originally entitled

Roots & Webs, San Francisco Film Society alumni

Sara Dosa—an associate producer on last year's

Inequality For All (2013)—boasted the world premiere of her first documentary feature

The Last Season (2014) [

Facebook]. With anthropological finesse and an open heart, Dosa aligns foraging with filmmaking as she tracks the tale of matsutake mushroom hunters in Oregon state, specifically the heartfelt interaction between an elderly Vietnam vet and a survivor of the Khmer Rouge who becomes his adopted son. What makes this season their last is not only the life cycle of the matsutake mushroom as threatened by undisciplined foraging and climate change, but the family's final opportunity to enjoy the mushroom hunting season together. Elegaic, and insightful as to the traumatizing effects of war on men from different backgrounds, I was quite taken by this documentary's narrative glimpse into one of America's relatively unknown subcultures. Word-of-mouth is rapidly spreading on

The Last Season and Dosa is assured a robust festival experience; for starters,

Melissa Silverstein's profile for

IndieWire.

SFIFF provided a refreshing touch of international glamour with the on-stage appearance of beloved French actor

Romain Duris, accompanied by director

Cédric Klapisch, for the one-off screening of

Chinese Puzzle (2013), the third installment in a trilogy that rivals Richard Linklater's "Before" Trilogy in its sophisticated purview of the maturation of cinematic characters over time. Ten years past, Klapisch delighted audiences with

L'Auberge Espagnole (The Spanish Room, 2002), introducing the charismatically frenetic Xavier (Duris) whose expectations of life are endlessly complicated by unfolding circumstance. Complication, however, veers into a kind of beauty, as Klapisch shifts his characters to New York City and sets their changing lives against a constantly shifting backdrop of urban existence. As someone deeply enamored with street art, I adored Klapisch's eschewal of ready architectural branding to explore the pedestrian and oft-overlooked street-level beauty of modern Manhattan.

This year's Persistence of Vision Award was awarded by SFIFF to

Isaac Julien, with

B. Ruby Rich in an on-stage conversation with Julien that was smart and far-reaching, and the first-ever projection of all nine screens of Julien's original installation

Ten Thousand Waves (2010) unified onto one screen. This afforded an omnipotent glimpse of the logical infrastructure of Julien's immersive film installation (recently at MOMA and San Diego), as well as the presiding emotional affects elicited by visual strategies of placement, replication, repetition, juxtaposition and inversion: negotiations of space and their attendant aesthetics. Every artistic choice triggered profound meditations, no less the green screen reveal incorporated as a dream sequence, or the intertextual citations to the film traditions of China. A satisfying, unique experience at the festival.

As mentioned by Rod Armstrong in his introduction to Philippine auteur

Lav Diaz's

Norte, the End of History (2013), it's possibly the longest film at SFIFF (clocking in at 250 minutes), at the same time that it's one of the shortest in Diaz's ouevre. I was swept up in this epic exploration of Dostevyskian themes regarding the nature of crime and its punishments, and ravaged by

Sid Lucero's savage performance as an existential law school dropout. Several scenes in

Norte felt like gliding vessels slowly filling up with grief, guilt, revelation and meaning. Elliptical interruptions in the narrative jolted the storyline into startling new trajectories. Profundity and depth earmark a familiar conceit of the free man imprisoned in his own skin and the incarcerated prisoner who has achieved freedom within.

Norte will be one of the featured highlights in the third edition of the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts focus on

New Filipino Cinema this Summer and well worth a second, if not repeated, viewings.

As someone currently in the grip of grief, hoping that movies will somehow ameliorate the pain, some films are as difficult to watch as they are soothing. Argentinian director

Juan Taratuto delivers a slow-burn low-key narrative in

La reconstrucción (The Reconstruction, 2013) suggesting that the grief of others can help reconstruct a life frozen by grief. I was frequently reminded throughout this film of the fairy tale of the Ice King whose frozen kingdom finally begins to melt when he issues his first tear. That's the challenge, isn't it? Not to allow grief to halt the flow of life. This film spoke as clearly to me as a friend sitting across a table.

As a San Franciscan, I will never forget November 1978, marked by two tragic events in rapid succession that left the city reeling in disbelief and horror. First, the Jonestown Massacre, and then the assassinations of mayor George Moscone and supervisor Harvey Milk, all within the same week. Time has a way of turning such historic tragedies into multiplex entertainment. The Massacre, in particular, was skillfully documented for

American Experience by Stanley Nelson in

Jonestown: The Life and Death of People's Temple (2006), which underscored (as

Nelson told me in interview) the death of utopian idealism in the United States.

Ti West resituates that cultural loss to an unspecified location in

The Sacrament (2013), programmed by Rod Armstrong for SFIFF's "midnight" series.

Contemporizing Jonestown's mass suicide through the use of digital cinematography and found footage tropes, West converts the memory of Jonestown into a piece familiar to his genre fanbase, eschewing his previous forays into supernatural horror to focus on the (natural?) horror of religious fanaticism and—perhaps even more horrific—the voyeuristic witnessing of same. Effective enough,

The Sacrament fails however to really bring anything new to the table except its prurience, although I'm pleased—after years of monitoring the work of

Joe Swanberg,

A.J. Bowden and

Kentucker Audley—to witness the unfolding maturation of their performances. They continue to come into their own within acting ensembles. Swanberg is a rooted actor with a gift for the comic, Bowden manifests grounded, serious virilities, and Audley exhibits a sensual befuddlement that's attractive. As "Father",

Gene Jones reigns over them all channeling Jim Jones to a chilling "t", right down to the characteristic shades.

Sultry tween

Josh Wiggins (reminiscent of River Phoenix and/or Leonardo DeCaprio in

their tween years) launches his career with a remarkably mature and nuanced performance in

Kat Candler's

Hellion (2014), proudly supported at the 57th edition of SFIFF by both the San Francisco Film Society and the Kenneth Rainan Foundation as part of their flagship funding initiative (which also helped to bring

Beasts of the Southern Wild and

Fruitvale Station, among other American independents, to multiplex screens). All of 15, Wiggins has captured a dream, co-starring against Idaho alumni

Aaron Paul, who adds yet another pigment to his palette of beleaguered masculinities. I predict it will be wonderful watching Wiggins and his talent grow up over the coming years. In retrospect, I'm grateful to have run into producer

Jonathan Duffy early on in the festival who encouraged me to catch the film. I met Jonathan last year at SFIFF's A2E Initiative when I interviewed him for Yen Tan's

Pit Stop.

Notable in part for being the first Costa Rican feature ever shown at SFIFF,

Por las plumas (All About the Feathers, 2013) achieves both Costa Rican and international traction, doing well at the home box office while inviting inquiry into the practice of creating national cinemas for international film festival networks. Whereas the film's aural landscape is undeniably indicative of its Costa Rican setting, its comic vignettes are universal in their quirky, deadpan, if somewhat amorphously assembled, delivery. Trained in Barcelona, and intriguingly well-versed in the mechanics of financing independent film through crowd funding and festival funding initiatives,

Neto Villalobos is another winning talent to watch in years to come. My thanks to Miguel Gomez for forwarding

a Vimeo link to one of Villalobos' music videos.

The first entry at SFIFF to go on rush,

Justin Simien's

Dear White People (2014) [

official site]—winner of the Sundance Film Festival's Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent—is a rather brilliant send-up of the campus comedy, skewering unfortunate headline events with brave, bracing critiques of racial inequities and identity stereotypes. A thoroughly entertaining and enlightening evening at the movies! I was especially impressed with

Tyler James Williams's comic turn as Lionel Higgins, the wary, wide-eyed gay fish-out-of-water; perhaps one of the best-written queer characters in recent memory, resonant with credible agency.

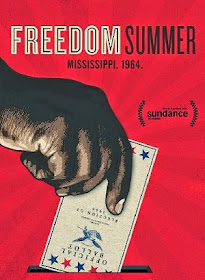

The continuing relevance of

Dear White People's comic scrutiny of race relations on contemporary American campuses seems decades distant and yet disturbingly allegiant to the efforts of college students in 1964 to secure voting rights for Black sharecroppers in racist Mississippi, as profiled in

Stanley Nelson's assured

Freedom Summer (2014). A competent use of archival footage combined with contemporary interviews with key participants, is further enrichened by illustrated re-creations, while the stinging haunt of the Supreme Court's recent decision to roll back key provisions of the Voting Rights Act hovers menacingly over the project. Unsung heroes are given prominent due in

Freedom Summer, specifically the charismatic Mississippi organizer

Fannie Lou Hamer, whose live testimony at the Democratic National Convention was kept off the networks' televised coverage by the less-than-subtle contrivances of President Johnson. Hamer's tombstone infamously reads: "I am sick and tired of being sick and tired." This is a tremendous historical document, necessary in the face of recent setbacks in American racial relations and increasing economic inequality.

Thomas Balmès' visually stunning documentary hybrid

Happiness (2013) deserves its Sundance prize in the World Cinema competition—the mountainous regions of Bhutan are filmed in all their snowcrested skyscratching grandeur—even as its staged narrative draws attention to itself, inducing suspicion as to the veracity of its documentary impulse. Its theme is honest however, as it questions the advance of modernization on traditional ways of life. Audiences can't resist being charmed by its nine-year-old protagonist Peyangki whose wide-eyed wonder never fails to solicit amused sentiment as he negotiates his monk's robe to perform cartwheels and to pretend he's flying. His first visit with his uncle to the nearby "city" of Thimphu to sell a yak to buy a television signifies Bhutan's uneasy negotiation with modernization. The seductive allure of television and the internet earns Bhutan's constitutional monarch his first-ever applause when during a public address he announces its allowance into the country—a country rated by

Business Week in 2006 as the happiest country in Asia—but reveals its unsettling and hypnotic grip in the film's final scenes, redefining the very notion of what "happiness" might mean.

Unfortunately, not every viewing experience at a festival can be a favorable one, no less for grief or a mild concussion. Within that camp I would have to include

Serge Bozon's

Tip Top (2013), misleadingly billed in SFIFF's program as a "screwball comedy". Along with brisk pacing, I expect screwball comedies to be characterized by warmth and wit, neither of which

Tip Top possesses, even as it sordidly rushes along with its sadomasochistic obsessions. All in all, I found the film to be a mean-spirited humiliation offered up for laughs. To each their own laughter.

Neither was I impressed with the moribund pacing and flat visuals of

When Evening Falls on Bucharest or Metabolism by Romanian auteur

Corneliu Porumboiu who seems intent on taking all magic out of moviemaking, making even the casting couch a plebian exercise. Maybe I just wasn't in the mood for endoscopy as entertainment? I can go to my doctor for that? To each their own endoscopy?

At least Taiwanese auteur

Tsai Ming-Liang exhibits visual audacity and a sense of mise en scène in his indulgent long takes in

Stray Dogs (2013). As Dennis Harvey culled from the protagonist of Porumboiu's

Metabolism, "reality deepens with the length of a camera shot", but that has unsettling implications when regarding "digital lensing's theoretically 'infinite' span". How much reality can one bear when one casually visits the moviehouse to either get away from reality or configure reality in more palatable terms? And how much does one have to bring to such temporal exercises in order to make it worth the time?

Ming-Liang is threatening to give up filmmaking because audiences just aren't "patient" enough for his cinema. He's disgruntled with audiences that want narratives to clip along at a steady pace or, as I've suggested, narratives that filet reality to appease an appetite for catharsis. I find Tsai Ming-Liang's complaints partly disingenuous, especially since he is an arthouse darling who does everything he possibly can to test the patience of his audiences. It strikes me that—when audiences become impatient with his films—he's achieved his creative goal, so why the complaint? To crib from Laura Nyro, "I've got a lot of patience, baby, but that's a lot of patience to lose." And lost it, I'm sorry to say, I have. Ming-Liang's latest snoozefest displays his talents for composition and atmosphere, yes, but gone are the humor and whimsy of his earlier films, and an appreciation for their structural beauty is harder won. But I appear to be a loud minority here at SFIFF when it concerns

Stray Dogs. Others have accepted the film on its own merits and countered that it "works" for them. Eminently more patient than I am, and probably more to be trusted in articulating these practices,

Brian Darr recently synopsized at

Hell on Frisco Bay: "Tsai's films have long developed recurrent themes of home and rootlessness, but with

Stray Dogs he uses these to create his rawest, bitterest attack on Taiwan's inequalities thus far. His first digital feature employs surveillance-style footage of his actor fetiche Lee Kang-sheng and two youngsters tramping through and setting camp in locations 'stolen' whether by crew or characters. It culminates in a fourteen-minute take that's simultaneously unforgiving and about forgiveness."