Thursday, April 25, 2013

SFIFF56—LATINBEAT

A cursory glance at the "Country Index" included in the program guide for the 56th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF) reveals several titles showing up more than once; a clear indicator of the state of international co-productions in today's festival landscape. Whereas at one time films in an international festival could be guided by the category of a national cinema, such a determinant now teeters on the quaint in the face of economic necessity and/or availability. The language or location of a film no longer signifies its nationality, neither does its director nor its talent. It now seems clear that money and money alone determines a film's country of origin and—in the case of international co-productions—the top financier gets to claim geographical rights, although indices such as SFIFF's "Country Index" gracefully allow shared (albeit tiered) national credits. Yet, just as the concept of a national cinema developed in film festival culture as a perceived reaction to Hollywood's hegemony—and as a tenuous distinction between an art film and a commercial film—it now seems new categories must be devised to distinguish artistry over commercial forces, with how one secures financing—from one country or many countries—emerging as a new style of auteurism for the 21st century. Of course, it's foolish to term it "auteurism", which is in itself a problematic ascription, and perhaps it's best to just call it good business sense in the service of creativity? Fundamentally, does it even matter where a film is from if a good story gets told? And seen? Or do we lose something when films evolve away from their distinct national characters?

While distinctions can still be sifted, however, and because old habits die hard, I offer up a preview of the Ibero-American and/or Latin American entries in this year's edition of the San Francisco International (absent shorts) and—since this is a distinction that may all but fade in the next decade or so—why not start with the official selections in the 2013 New Directors Narrative Feature Competition, where those coming up over the horizon matter more for being new on the scene than where they're from?

The Cleaner / El Limpiador (Adrián Saba, Peru, 2011)—As synopsized by Robert Avila at SFIFF: "As a mysterious epidemic eviscerates Lima's adult population—but spares its children—a solitary middle-aged forensic worker discovers an orphaned boy at one of his cleanup sites and decides to shelter the traumatized youth until he can find a relative to take him. As time passes, a subtle transformation takes hold of both man and child in this gently haunted and affecting study of social alienation and redemption."

The Cleaner is the perfect film to start out this problematic purview, because it's a wholly Peruvian production and yet—as Michael Hawley has suggested in his capsule review—while he can't be sure how, or even if, Saba's film is commenting upon contemporary Peruvian society, "it's clear that his distinct voice is one we should be hearing more of in the future." The film has certainly gained pedigree on the festival circuit. It first came to my attention at the Palm Springs International Film Festival (PSIFF) earlier this year, having already received a New Directors Award Special Mention at its San Sebastián premiere. It ended up winning the New Voices / New Visions Grand Jury Prize at PSIFF 2013 where the jurors remarked: "While it is set in the midst of a deadly epidemic, this film eschews the usual genre tropes and instead offers an aesthetically distinctive, minimalist portrayal of a human connection at a time when it seems all hope is lost. The director creates an eerie, strangely calm atmosphere which is carefully controlled but never feels forced, and without sensationalism or overt sentiment, allows a touching bond to develop between his lead characters, a lonely old man and a young boy. With The Cleaner, Adrian Saba has created a singular, unusual and intimate tale which stayed with us long after viewing."

I regretted missing The Cleaner at PSIFF—and the opportunity to hear Saba discuss his film with his audience—but was pleased to catch it at the recent Panamá International Film Festival (IFF Panamá) where lead actor Víctor Prada (last seen in Octubre) accompanied the film and interacted with his audience. There Diana Sanchez categorized the film as "an inspired combination of science fiction and Latin American neorealism" where "kindness and generosity reign … despite the surrounding death and decay." By "science fiction", I understand her to mean that The Cleaner is a "near future" narrative, similar to Alex Rivera's Sleep Dealer (2008). Without question, The Cleaner evokes an eerie temporal alterity and rewards the patient viewer with heartfelt flourishes.

Habi, the Foreigner / Habi, la extranjera (María Florencia Álvarez, Argentina / Brazil, 2013)—As synopsized by SFIFF: "Highlighted by an impressive and subtle performance by Martina Juncandella, first-time director María Florencia Álvarez's film traces a 20-year-old woman's spontaneous attempt to create a new identity for herself as a Lebanese orphan in Buenos Aires. Sensitively examining the role of culture in self-definition, Habi, the Foreigner is a beguiling coming-of-age story detailing the feeling of being an outsider in your own land."

Habi had its premiere at the Berlin Film Festival where Stephen Dalton dispatched to the Hollywood Reporter that he found the film to be a "puzzling portrait of cultural tourism taken to extremes." Co-produced by Walter Salles and sporting its North American premiere at SFIFF, Dalton describes the film as "delicately crafted" but found the film's plot "slender, open-ended and frustratingly opaque in places." He cautions that though the film "poses some interesting questions about identity and self-reinvention", it never fully answers them. "While Juncadella gives a quietly luminous performance," Dalton continues, "the script offers no persuasive motivation for Analia's bizarre experiment in cultural tourism. Is her attraction to Islam a rebellious protest against her stifling family? An unconscious reaction to the demonization of Muslims in the wake of 9/11? Just a random accident? We can only guess."

The Towrope / La Sirga (William Vega, Colombia / France / Mexico, 2012)—As synopsized by Miguel Pendás at SFIFF, "A shy teenage girl, cast out of her home by a fire which also destroyed her parents, seeks shelter with a handful of denizens of the shores of a mist-shrouded lagoon in this coming-of-age tale set in the lonely, enchanted landscapes of the high Andes where everyone quietly nurtures illusions of success and fantasies of intimacy with other humans."

At Variety, Rob Nelson reviewed the film from the Cannes Film Festival where it was a contender for the New Directors Prize: "Proving that it's still possible for a young director to deliver a film that's committed more to ambiguity than to clarity, and as much to sound as to image, William Vega's La Sirga is a thoroughly engrossing art film that … emphasizes nuance over narrative." At White City Cinema, Michael Glover Smith writes: "Though it feels at times like a checklist of elements designed to go over well at international film festivals (war-torn country, child protagonist, liberal-humanist tone), this is a small, well-made film, bolstered by gorgeous footage of the Andes mountains and an evocative performance by [Joghis Seudin] Arias, whose expressive face could be that of a silent film actress. A vivid snapshot from a remote corner of the earth that's well worth a look." At Critic Speak, Danny Baldwin asserts "it's important to discuss La Sirga … because through its microcosmic symbolism, the film has much to say about the corruption and social inequity that still plague several South American nations." Film Movement has picked up the film for North American DVD distribution and offers their press kit in PDF.

They'll Come Back / Eles Votram (Marcelo Lordello, Brazil, 2012)—As synopsized by Julia Barbosa: "A potent exploration of class and adolescence, They’ll Come Back tells the story of Cris, a privileged 12-year-old who—after being left on the side of the road as punishment for her and her brother's constant bickering—embarks on a journey that will open her eyes to a world she never knew as she tries to find her way home."

Winner of the Candango Trophy at the Brazilia Festival of Brazilian Cinema for Best Film, Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress, nominated for the Tiger Award at the 2013 edition of the Rotterdam International, and featured in Lincoln Center's New Directors / New Films, They'll Come Back—according to Tomas Hachard at Slant—"shares both a location and theme (the country's intensifying class divisions) with Kleber Mendonça Filho's Neighboring Sounds, but distinguishes itself in method: Filho never showed the Recife slums, preferring instead to have them figure absently as a potential source of menace for his film's middle-class residents, whereas Lordello allows himself more explicit juxtapositions." Hachard praises the film's "high-wire act that They'll Come Back manages to pull off. Lordello doesn't temper any anger toward the status quo and privileged classes, but by emphasizing [lead character] Cris's shift from seclusion to emerging humility and empathy, he also leaves a space open for reconciliation." At Filmleaf, Chris Knipp praises Lordello's "sly and original script" and notes that the "film's class-conscious agenda is transparent but made convincing through a steady accumulation of detail."

Shifting away from the New Directors Narrative Feature Competition, SFIFF56 offers a Spanish debut for their 2013 Golden Gate Award for Documentary Feature Competition, co-presented by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts.

The Search for Emak Bakia / La casa Emak Bakia (Oskar Alegría, Spain, 2012)—As synopsized by Miguel Pendás: "In 1926, avant garde artist Man Ray shot a film titled Emak Bakia, a Basque expression that means 'Leave me alone.' Intrigued by the fanciful conundrums and coincidences of Ray and his art, filmmaker Oskar Alegría ignores Ray's dictum and sets out to plumb the mysteries of Emak Bakia, leading to an unforgettable journey of whimsical discoveries and charming surprises."

At the San Francisco Chronicle, Walter Adieggo observes that there are "plenty of humorous and intriguing byways" in Alegría's pilgrimage to solve the mystery of Man Ray's experimental shot film and assesses, "The journey is the whole point, of course." Indiewire adds: "A path that was covered and later forgotten is usually a good starting point for a documentary. …But Alegría's aim is not so much to 'document' but to 'explore', and so he goes deep into (Super)Man Ray's footprints like a film diver, like someone who explores the deep, what we can't see on the surface, bringing something that is far-off but completely new. With invention as his North he playfully places his film on top of another—the metaphor about the referent—and brings those remains from the past in the form of a palimpsest, subverting the emphatic gesture of avant-garde art and transforming it into a classic one. But at the same time, Alegría tries to build his home/film and does so with an exceptional use of resources, from collage to symmetry, and from visual parallelism to written irony. As in every good story, this film narrates a journey in search of (inventing) a house we all wish we could live in." At the East Bay Express, Kelly Vance suggests that a film like The Search for Emak Bakia is the heart and true spirit of programming at SFIFF, which he characterizes as a "grassroots appreciation of art for art's sake, the more rough-edged the better. Bay Area audiences are not especially impressed with glitz. Filmmakers mean more than movie stars here." As to The Search for Emak Bakia specifically, Vance writes: "It's kind of a surrealist scavenger hunt, with clowns, tombstones, eyelids, happenstance, and coincidence."

Here are the remainder of Ibero-American and Latin American entries rounding out SFIFF's line-up, alphabetically arranged.

After Lucia / Después de Lucia (Michel Franco, Mexico / France, 2012)—As Joanne Parsont synopsizes: "After his wife's death in a car accident, Roberto moves to Mexico City with his teenage daughter Alejandra. While father and daughter are inherently close, their repressed grief and lack of communication threatens to unhinge them when Ale becomes the victim of brutal bullying at school."

My previous entry on After Lucia can be found here on The Evening Class.

The Artist and the Model / El artista y la modelo (Fernando Trueba, Spain, 2012)—As synopsized by Miguel Pendás: "An aging painter (Jean Rochefort) and his wife (Claudia Cardinale) discover a beautiful, waiflike young woman wandering the streets whom they take in as his model in this story by 1994 Oscar® winner Fernando Trueba (Belle Epoque) about artists and their muses."

Winner of the Silver Seashell for Best Director at the San Sebastián Film Festival, and co-written by Jean-Claude Carrière, The Artist and the Model—according to Jonathan Holland at Variety—emerges as "an exquisitely crafted miniature about the creative rebirth of an aging sculptor" that "brings the same craft and care to its subject as its titular artist does to his own work." Though admirable, Holland nonetheless finds The Artist and the Model "oddly remote" and a "kind of study fashioned expressly for the arthouse." At the San Francisco Bay Guardian, Kimberly Chun writes: "The horror of the blank page, the raw sensuality of marble, and the fresh-meat attraction of a new model—just a few of the starting points for this thoughtful narrative about an elderly sculptor finding and shaping his possibly finest and final muse." She adds: "Done up in a lustrous, sunlit black and white that recalls 1957's Wild Strawberries, The Artist and the Model instead offers a steady, respectful, and loving peek into a process, and unique relationship, with just a touch of poetry."

Chaika / Seagull (Miguel Ángel Jiménez Colmenar, Spain / Georgia / Russia / France, 2012)—As synopsized by Michelle Devereaux: "In the startlingly bleak yet beautiful Chaika, Ahysa (Salome Demuria), a young Kazakh prostitute who gives birth to an illegitimate son, finds a home with a downtrodden yet sympathetic sailor in the brutal winter wastelands of expansive, empty Siberia. Trapped in the moonscape-like terrain while longing to take flight, Ahysa suffers the tragic effects of family resentments and her own independent spirit." Winner of the Golden Frog at Cameraimage for both Best Director's Debut and Best Cinematographer's Debut.

Crystal Fairy (Sebastián Silva, Chile, 2013)—As synopsized by SFIFF: "An American in Chile (Michael Cera) joins up with three lanky brothers and a spaced-out hippie chick to seek out the perfect high of a desert psychedelic in this partially improvised road movie from Chilean director Sebastián Silva, whose The Maid won a 2009 Sundance Jury Prize. Merging Woody Allen-esque humor and Ugly American dickishness, Cera is a revelation."

Silva won an award for directing at Sundance where the jurors stated: "One film above all the films we saw felt organic and unassuming; we fell in love with the characters without ever knowing too much about them, embarking with them on a fascinating journey infused with humor and discovery." At Screen Daily, Anthony Kaufman writes: "Director Silva is after something deeper than a mere drug movie, touching upon the fine lines between the fronts people put up and who they really are, as well as a plea for tolerating other's differences." At IonCinema, Nicholas Bell categorizes Crystal Fairy as a "loopy endeavor that is most certainly unpredictable" but complains that its hilarious opening act devolves into a painstaking third act that's "unable to achieve the incredible high it achieves during its setup." At First Showing, Ethan Anderton concurs: "In the end, Crystal Fairy has an interesting opening title sequence, a good amount of laughter, but a story that never quite comes together as complete."

The Future / Il Futuro (Alicia Scherson, Italy / Germany / Chile / Spain, 2012)—As synopsized by Mel Valentin: "Through their relationship with a pair of bodybuilders, an orphaned brother and sister stumble on an opportunity they can't refuse: seemingly easy money by way of a former Mr. Universe turned reclusive movie star. This adaptation of Roberto Bolaño's novella isn't a standard issue crime drama. Ultimately, it's something else altogether: a poignant meditation on time, aging, identity and the movies."

Winner of the KNF Award at the Rotterdam International, Nicholas Bell at IonCinema writes: "While intriguing, and at moments, striking, there's an unfortunate distance from the events and characters in Scherson's film, and an undeniable indifference to what's unfolding before us." At Smells Like Screen Spirit, Don Simpson states that "Il Futuro exists in a surreal fugue state in which strange events are explained by the siblings' damaged psychological state after their parents' catastrophic accident." At Exclaim, Robert Bell characterizes Il Futuro as "wildly impressionistic" and culls out an underlying subtext of "oedipal relations and gender performance."

Google and the World Brain (Ben Lewis, England / Spain, 2013)—As synopsized by Steve Ramos: "Veteran documentarian Ben Lewis travels the world speaking to futurists like Wired Magazine co-founder Kevin Kelly and scholars such as Harvard University cultural historian Robert Darnton for his mind-bending film Google and the World Brain, a fascinating look at the Google Books Project and its global implications."

At Screen Daily, Anthony Kaufman writes: "The documentary convincingly points out that Google's ambitions [to create a massive digital library by scanning millions and millions of books, fulfilling the promise of a 'universal library'] aren't entirely philanthropic, but meant to continue to improve their Search algorithms, and find ways to monetise their enormous stores of information." Though describing the documentary as "largely staid," Kaufman nonetheless proposes that Google and the World Brain "manages to raise intriguing questions about the future of books and the corporate control of information in the Internet age." At Ioncinema, Jordan M. Smith finds Google and the World Brain a "fluently astute and alarmingly predictory film" that "revolves around conflict between intellectual freedom, copyright remembrance and corporate ascendancy" and that suggests a need to find "a legal path into the future." At East Bay Express, Kelly Vance writes: "Google and the World Brain stands out for its sizzling topicality…. Futurists and similar pundits insist, among other things, that Google exists to monetize knowledge, and that despite its paid publicity, Google Books is not a library but a bookstore. If Google were somehow to own every book, all knowledge would carry a price tag."

Mai Morire (Enrique Rivero, Mexico, 2012)—As synopsized by Jesse Dubus: "In the ethereal, nearly pre-Columbian landscapes of the Mexican town of Xochimilco, a stoic woman returns home to care for her 99-year-old mother nearing the end of her life. Haunting and meditative, Mai Morire shows a woman's experience of her mother's death not as a tragedy, but as a natural, even beautiful event in her life."

Winner of a Special Jury Award for director Rivero at the Huelva Latin American Film Festival and Best Technical Contribution for cinematographer Arnau Valls Colomer at the Rome Film Fest, Lee Marshall writes at Screen Daily: "This is a film whose drama lies as much in the play of light on water, fields, trees and distant mountains as in the minimal dialogue and interactions between its few characters." But he complains about the film's "funereal" pacing and wishes that the film's "exaggerated understatement" were "just a little less reticent, and a little more legible." At The Hollywood Reporter, Jordan Mintzer states that Mai Morire is a "stunningly shot slice of Mexican realism, but one that would have fared better had it not leaned so heavily on narrative minimalism. …Still, as a meditation on family, ritual and the passing of time, it packs a quiet punch."

Night Across the Street / La noche de enfrente (Raúl Ruiz, France / Chile, 2012)—As synopsized by Judy Bloch: "Cinema sadly lost Raúl Ruiz in 2011, but this posthumously released film, shot in his native Chile, brings back the elegance of his straight-faced surrealism in the story of a man nearing retirement and death who indulges his love for words and conjures up his childhood heroes, from Beethoven to Long John Silver. Ruiz's visual message from beyond is that death is just a word, and not to be feared."

Quite a lot has been written about Night Across the Street, but I would single out write-ups by Daniel Kasman (MUBI) and Justin Chang (Variety). But don't stop there.

Monday, April 22, 2013

SFIFF56—Michael Hawley Previews the Line-up

Museum Hours—When I read that SFIFF56's Persistence of Vision Award winner was to be one Jem Cohen, I drew a complete blank. An IMDb search revealed he co-directed the acclaimed 2000 documentary Benjamin Smoke and a slew of familiar R.E.M. videos. Now I've seen his fascinating and unclassifiable new film and declare it my favorite of all the works I previewed for this year's festival. On the surface, Museum Hours follows a developing friendship between Johan, a distinguished-looking ex-punk band manger turned museum guard and Anne, a broke and bewildered Canadian woman in Vienna visiting her hospitalized distant cousin. At its heart, Museum Hours is also a tribute to the riches of Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum, most famous for the Pieter Brueghel collection of which we're given an on-screen docent tour. In both conversation with Anne and in voiceover, Kunsthistorisches guard Johan ruminates on the purpose, origin and future of museums, and what it's like for him to be an observer of other people observing art. Museum Hours' most whimsical moment follows a discussion of frank nudity in an Adam and Eve painting with a cut to several museum visitors who are also, quite frankly, nude. Cohen's film frequently flees the museum's confines and becomes an ode to Vienna in wintertime, albeit a shabbier Vienna than one sees in travel brochures. While the movie operates on many other levels, the festival's "Hold Review" restrictions prohibit me from saying a whole lot more. Museum Hours screens just once, at the Golden Gate Persistence of Vision Award program which will also feature an on-stage conversation with Jem Cohen. My advice is not to miss it.

The Strange Little Cat—The little cat is the only thing that isn't strange in this mini-masterpiece of choreographed chaos from Ramon Zürcher, a film student whose little movie made big noise at this year's Berlin Film Festival. Save for a few flashbacks, the film is staged entirely within a cramped apartment as an extended German family spends the day hanging out and preparing meals. The kitchen is ground zero for all manner of hustle-bustle, petty arguments and wounding both physical and psychological. A toy helicopter flies through the air, sausages squirt grease, a popping cork extinguishes the ceiling light and a little girl screams every time an appliance is in use—all while grandma naps in the next room. Zürcher's camera spends most of its time hovering at belly button level, when it isn't foot-fetishizing or obsessing over a hair floating in a glass of milk. Meanwhile, a hyperactive sound design refuses to be ignored. What's nice is that amidst all this craziness, Zürcher's characters are never reduced to human cartoons, but emerge as real people with relatable quirks and foibles.

Good Ol' Freda—In 1961, a Liverpool typing pool secretary named Freda Kelly got taken to the Cavern Club for lunch. The 16-year-old dropout ingratiated herself with the band she saw perform that afternoon and was soon hired by manager Brian Epstein to run The Beatles fan club. She held that pleasurable but arduous position for 11 years. Until now the charmingly self-effacing Kelly, who remains a secretary at age 67, has remained quiet about her front-row seat to Beatlemania. She was fiercely loyal to the band then and remains so now, meaning no real dirt gets dished here. But she is full of lovely anecdotes, such as when she convinced Ringo to sleep on a pillowcase sent in by an adoring fan, or when she made John get on his knees and beg her to stay after getting sacked for spending too much time in the Moody Blues dressing room (she was dating a band member). Other subjects include Epstein's legendary tantrums and Kelly's close relationships with the band's family members. Apparently, there was no problem securing rights to use original Beatles recordings in the soundtrack. While director Ryan White's documentary never strays from a talking heads and archival materials template, it should be considered essential for fans—and really, who isn't one? Be sure and stay for a video message from Ringo that plays over the closing credits.

Sofia's Last Ambulance—The workaday routine of a paramedic emergency response team in Bulgaria's capital is the subject of this verité documentary from director Ilian Metev. Over the course of its 75 minutes, we ride along with Krassi the doctor, Mila the nurse and Plamen the driver as they bounce along pothole-ridden streets in a race against time and a wrecked system. A dashboard-mounted camera alternately observes the road ahead and stares at our protagonists parked in the front seat. The camera then goes into hand-held mode as it films the trio in action, sticking tightly on the crew and keeping those they're helping out of frame as much as possible. In the case of a woman whose head has been eaten by worms, that's a very good thing. Spurts of intensity are contrasted with periods of downtime, in which these colleagues who are clearly fond of each other chain smoke, banter and kvetch about things like being put on hold for 30 minutes when phoning dispatch for a new assignment. "This country is broken," sighs Plamen, the young driver whose changing hairstyles indicate that filming took place over an extended period.

The Cleaner—There's an epidemic of lethal lung infections in Lima, Peru and it's middle-aged sad sack Eusebio's job to clean up the mess. On one particular assignment he discovers newly orphaned Joaquin hiding in a closet. He brings the skittish child home to his rudimentary apartment and the two gradually bond. Eusebio spends the rest of the film tracking down Joaquin's relatives—no easy task thanks to overwhelmed social services and uninterested bureaucrats. Director Adrian Saba's tenderly somber feature debut employs tropes common to contemporary Latin American art cinema—a stationary camera, impressive compositions, minimalist electronic scoring and barely perceptible humor. In one scene, Joaquin asks to be read a bedtime story and all Eusebio has available is the manual for his TV set. Unlike a lot of Latin American art cinema, however, The Cleaner moves along at a relatively brisk pace. While I can't be sure how, or even if, Saba's film is commenting upon contemporary Peruvian society, it's clear that his distinct voice is one we should be hearing more of in the future.

What Maisie Knew—Six-year-old Maisie is a poor little rich girl caught in a custody battle between her unmarried rock star Mom (Julianne Moore) and art dealer Dad (Steve Coogan). When Dad marries the nanny (Joanna Verderham) out of the blue, Mom ties the knot with a hot young bartender (Alexander Skarsgard) out of revenge. How Maisie survives thanks to the love and care of her newly-acquired step-parents is the focus of this new film from former S.F filmmakers Scott McGehee and David Siegel (Suture, Bee Season). They fully succeed in conveying the conflict from a child's POV, in no small part aided by a heartbreaking titular performance by Onata Aprile. It strains credulity, however, that in light of the insecure harpie and boorish slimeball she has for parents, angelic Maisie never once "acts out." Other elements of plot and characterization are wobbly, but that doesn't stop What Maisie Knew from being an engaging and frequently powerful entertainment that should serve well as SFIFF56's Opening Night film. Seen at a SFIFF56 press screening.

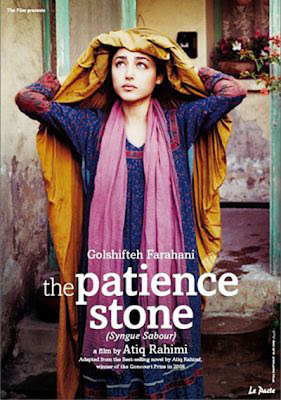

The Patience Stone—In an unnamed war-torn country clearly meant to be Afghanistan, an abandoned woman spends her days verbally unburdening herself of heretofore unspeakable thoughts over the body of her comatose husband, a mujahedeen who's been wounded in a brawl. As battles rage around her home, she seeks help from a long lost aunt, now a prostitute, to care for her two little girls. Additional solace appears in the form of a shy, stuttering soldier, himself an abused former bacha bazi, with whom she'll share a guarded intimacy. Director Atiq Rahimi has adapted his best-selling novel for the screen with the help of legendary French screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, although their decision to fashion the film as basically one long monologue can feel unnecessarily stodgy. The cinematography, production design and Golshifteh Farahani's lead performance are flawless. The title derives from Persian lore in which a person pours all their tribulations into a stone until it shatters, thereby bringing deliverance. Seen at a SFIFF56 press screening.

Habi, the Foreigner—In this low-key feature debut from Argentine director María Florencia Álvarez, a young woman arrives in a new city, checks into a seamy pension and begins insinuating herself upon the local Muslim community. Director Álvarez parcels out information very slowly. Eventually we learn we're in Buenos Aires and the woman is of Lebanese descent, but the question of where she came from and why she left largely goes unanswered. Most of the film is spent watching her try on this new personage—wearing a hijab, learning to pray, sampling Arab foods—and dealing with conflicts of the secular world as they arise. A romance with a handsome Argentine Arab leads to what could be an enormous revelation about her past, but the film weirdly takes it nowhere. Habi, the Foreigner works as a portrait of someone testing a new identity, though it ultimately proves more frustrating than enigmatic and mysterious.

After Lucia—Following the death of their spouse / mother, an upper class father and daughter move to Mexico City and begin a new life. The father, a chef, has come to open a new restaurant but is having an extremely hard time coming to terms with grief. His high-school aged daughter, however, has been accepted by the cool kids at school and appears to be doing well. That changes when a moment of poor judgment launches a wildly over-the-top onslaught of peer bullying made all the more aggravating by the girl's astonishing passivity and surrender to fate. As with Michel Franco's previous film Daniel and Ana, in which a wealthy brother and sister are kidnapped and forced to have sex with each other on film, I suspect this director is less interested in exploring so-called social issues than he is in dragging our faces through muck. At Cannes last year, the Un Certain Regard jury awarded After Lucia its top prize, and it is certain to be one of the most talked about films at SFIFF56. Seen at the 2013 Palm Springs International Film Festival.

Short Takes—Three other Palm Springs crossover films appear in the SFIFF56 line-up and all are highly recommended. Rama Burshtein's Fill the Void is a stirring and nuanced tale set within Tel Aviv's Orthodox Hasidic community, whereby a young woman is asked to put aside her own romantic aspirations and marry her sister's husband after she dies during childbirth. The film opens in the Bay Area on June 7, but director Burshtein and the amazing Hadas Yaron, who won the Best Actress prize at last year's Venice Film Festival, are expected at the SFIFF56 screenings. Next, those who were blown away by Russian director Sergei Loznitsa's My Joy when it screened at this festival two years ago, won't want to miss his latest, In the Fog. While stylistically less audacious, this saga about the ambiguity of wartime morality set in 1942 Byelorussia is no less haunting, complex and visually arresting. Finally, Hungarian director Bence Fliegauf returns to the festival for the first time since 2005's memorable Dealer, with his latest film Just the Wind. This Berlin Silver Bear winner is based on real events and uses the plight of one Romany family to expose ethnic prejudice in modern day Hungary. Employing methods similar to early Dardenne brothers' work—grainy, close-up hand-held camera work and non-pro actors—Fliegauf follows his characters through a day of mounting tensions en route to an inevitably tragic and unforgettable climax.

Cross-published on film-415.

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—PALABRAS MÁGICAS (MAGIC WORDS, 2012) / CARRIÈRE, 250 METROS (CARRIÈRE, 250 METERS, 2013)

Two documentaries screened back-to-back at IFF Panamá's new venue, the Teatro Anita Villalaz (situated in the National Institute of Culture), both of which utilized the poetics of memory to further their narratives, albeit by slightly different strategies. Mercedes Moncada Rodríguez's documentary Palabras Mágicas (Magic Words, 2012)—situated in IFF Panamá's "Stories From Central America" sidebar—configured memory as an expression of history. In fact, her documentary quite brilliantly demonstrated how it is the commonplace nature of our everyday struggles that truly places us within the historical moment, which unfolds as it occurs but is given context and underscored import as it is remembered, suggesting as well the ongoing tension between popular memory and official accounts of history.

Her's is a sad reflection on the betrayal woefully built into revolutionary zeal. As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "Magic Words underlines how the Revolution and the subsequent government, rather than usher in a wave of radical change, simply offered proof to the notion that history is destined to repeat itself." With so much being said these days about the loss of a moral compass, Palabras Mágicas cautions that—when a people lose their point of reference—they don't know where to go and, as a consequence, end up circling back again and again, disoriented, repeating the lessons they have not learned from history.

As Rodríguez introduces her own film: "Here in Lake Managua, reside the dissolved ashes of [Augusto César] Sandino. Will the contents change the container? Lake Xolotlán is possessed by him, Sandino. If this is true then this is all of Managua, because it is the city's sewer and the waste comes from us all. I am like this lake that—like Nicaragua—is not like a flowing river always renovating itself, for I hoard and save. Palabras Mágicas is my emotional perspective of the revolution in Nicaragua."

By jumping back and forth in time Rodríguez seeks to juxtapose the lofty promises of the Revolution fueled by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (who took their name and inspiration from Sandino) and provocatively aligns them against the deflated compromises that resulted in the Sandinistas eventually behaving no differently than their ousted predecessor Anastasio Somoza Debayle, leaving the Nicaraguan people no better off than before the Revolution. This structural strategy, rife with potential for poetic counterpoint, proved sometimes confusing, though its basic thrust of how the Somoza regime and the Sandinistas simply switched abusive authorities came across loud and clear.

It's also of note to state that Latin American documentaries rarely flinch from portraying U.S. intervention in an appropriately harsh light. In fact, the perception of Sandino as a Nicaraguan hero is precisely because of his resistance to U.S. domination. This remains for me one of the most difficult aspects of being a U.S. citizen—knowing of our government's sponsorship of dictatorships that have overthrown Latin American democracies; knowing that each American citizen is guilty by implication—especially for having no political will to do anything about it. In this sense U.S. citizens are as disoriented as Nicaraguans, having lost their moral point of reference. Through her emotional perspective, Rodriguez beautifully comments on the hypocrisies of military governments on all sides of their wars.

I was stunned by archival footage of the Nicaraguan resistance lifting cobblestones out of the streets to fight the Somozan forces, especially in light of the fact that Somoza owned most of the cobblestone factories in Nicaragua, whose product he sold back to his own country to pave roads, never dreaming that these roads would be ripped up by hand and that these stones would one day be used against him, victoriously leading to his regime's collapse. Visually, it reminded me of the student protests in Paris in May 1968 where, likewise, cobblestones were dislodged to wield as projectiles.

Juan Carlos Rulfo's affectionate portrait of scenarist Jean-Claude Carrière likewise yokes memory to poetry, but more from the individual perspective of an older man's nostalgia for days gone by. I could relate so much to this elder statesman recalling his youth of 40 years past, back when being a hippie meant running away from the culture of our parents and dreaming that love and peace could change the world. How have we come, Carrière asks in voiceover, from peace and love to 9/11? 40 years later, I am asking many of the same questions.

The title of Rulfo's documentary Carrière, 250 Metros (Carrière, 250 Meters, 2013) references the fact that his family's grave plot lies no more than 250 meters from the house where he was born. But what begins at first as a circumscribed tribute to his family roots in a small village in Languedoc expands outwards into a compelling exploration of the cities Carrière has claimed throughout the course of his creative career. His deep taproot into the soil of his family home offsets his creative rootlessness, which has propelled him outward, seeking creative adventure over the face of the planet. Thus, Carrière , 250 Metros becomes as much a meditation on the acquisition of space as it is on the diminuation of time; a clocked cartography wholly personal and hand-drawn.

Carrière's recollections of his friendships and creative collaborations with Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel recount their ritual pilgrimages to Toledo, Spain, thereby delighting in the comforting patterns that enforce friendship. And Carrière's love for Miloš Forman is beautifully captured by photojournalist Mary Ellen Mark, both in their youthful questing embraces, and their elderly assured ones.

I left this film quite wistfully, wandering through the labyrinthine streets of Casco Viejo and—taking Carrière's cue—imagining the lives within half-lit residences, pausing at a corner to watch a group of children spilled out onto the sidewalk and into the street singing along with a song playing on a radio. It moved me to tears. A sultry breeze off the water made me feel that I was floating on air, and traveling—as Carrière suggested—not to see things, but to not see things; that is, to go within, to use travel as introspection, to allow the beautiful distractions of the world to wash over me as I center myself within.

Her's is a sad reflection on the betrayal woefully built into revolutionary zeal. As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "Magic Words underlines how the Revolution and the subsequent government, rather than usher in a wave of radical change, simply offered proof to the notion that history is destined to repeat itself." With so much being said these days about the loss of a moral compass, Palabras Mágicas cautions that—when a people lose their point of reference—they don't know where to go and, as a consequence, end up circling back again and again, disoriented, repeating the lessons they have not learned from history.

As Rodríguez introduces her own film: "Here in Lake Managua, reside the dissolved ashes of [Augusto César] Sandino. Will the contents change the container? Lake Xolotlán is possessed by him, Sandino. If this is true then this is all of Managua, because it is the city's sewer and the waste comes from us all. I am like this lake that—like Nicaragua—is not like a flowing river always renovating itself, for I hoard and save. Palabras Mágicas is my emotional perspective of the revolution in Nicaragua."

By jumping back and forth in time Rodríguez seeks to juxtapose the lofty promises of the Revolution fueled by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (who took their name and inspiration from Sandino) and provocatively aligns them against the deflated compromises that resulted in the Sandinistas eventually behaving no differently than their ousted predecessor Anastasio Somoza Debayle, leaving the Nicaraguan people no better off than before the Revolution. This structural strategy, rife with potential for poetic counterpoint, proved sometimes confusing, though its basic thrust of how the Somoza regime and the Sandinistas simply switched abusive authorities came across loud and clear.

It's also of note to state that Latin American documentaries rarely flinch from portraying U.S. intervention in an appropriately harsh light. In fact, the perception of Sandino as a Nicaraguan hero is precisely because of his resistance to U.S. domination. This remains for me one of the most difficult aspects of being a U.S. citizen—knowing of our government's sponsorship of dictatorships that have overthrown Latin American democracies; knowing that each American citizen is guilty by implication—especially for having no political will to do anything about it. In this sense U.S. citizens are as disoriented as Nicaraguans, having lost their moral point of reference. Through her emotional perspective, Rodriguez beautifully comments on the hypocrisies of military governments on all sides of their wars.

I was stunned by archival footage of the Nicaraguan resistance lifting cobblestones out of the streets to fight the Somozan forces, especially in light of the fact that Somoza owned most of the cobblestone factories in Nicaragua, whose product he sold back to his own country to pave roads, never dreaming that these roads would be ripped up by hand and that these stones would one day be used against him, victoriously leading to his regime's collapse. Visually, it reminded me of the student protests in Paris in May 1968 where, likewise, cobblestones were dislodged to wield as projectiles.

Juan Carlos Rulfo's affectionate portrait of scenarist Jean-Claude Carrière likewise yokes memory to poetry, but more from the individual perspective of an older man's nostalgia for days gone by. I could relate so much to this elder statesman recalling his youth of 40 years past, back when being a hippie meant running away from the culture of our parents and dreaming that love and peace could change the world. How have we come, Carrière asks in voiceover, from peace and love to 9/11? 40 years later, I am asking many of the same questions.

The title of Rulfo's documentary Carrière, 250 Metros (Carrière, 250 Meters, 2013) references the fact that his family's grave plot lies no more than 250 meters from the house where he was born. But what begins at first as a circumscribed tribute to his family roots in a small village in Languedoc expands outwards into a compelling exploration of the cities Carrière has claimed throughout the course of his creative career. His deep taproot into the soil of his family home offsets his creative rootlessness, which has propelled him outward, seeking creative adventure over the face of the planet. Thus, Carrière , 250 Metros becomes as much a meditation on the acquisition of space as it is on the diminuation of time; a clocked cartography wholly personal and hand-drawn.

Carrière's recollections of his friendships and creative collaborations with Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel recount their ritual pilgrimages to Toledo, Spain, thereby delighting in the comforting patterns that enforce friendship. And Carrière's love for Miloš Forman is beautifully captured by photojournalist Mary Ellen Mark, both in their youthful questing embraces, and their elderly assured ones.

I left this film quite wistfully, wandering through the labyrinthine streets of Casco Viejo and—taking Carrière's cue—imagining the lives within half-lit residences, pausing at a corner to watch a group of children spilled out onto the sidewalk and into the street singing along with a song playing on a radio. It moved me to tears. A sultry breeze off the water made me feel that I was floating on air, and traveling—as Carrière suggested—not to see things, but to not see things; that is, to go within, to use travel as introspection, to allow the beautiful distractions of the world to wash over me as I center myself within.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—DANS LA MAISON (IN THE HOUSE, 2012)

As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "A high school French teacher (Fabrice Luchini) becomes implicated in a series of increasingly precarious and unethical acts when he encourages a student to explore his fantasy of insinuating himself into a classmate's home. François Ozon's latest film fuses psychological thriller with class-conscious comedy, creating a twisty meditation on voyeurism and the dangers of storytelling."

Adapted from Juan Mayorga’s play The Boy in the Last Row, Dans La Maison (In the House, 2012) reunites Ozon and Luchini (who worked together on the clever Potiche), but to less winning effect, partly because it attempts to fuse too much together and reveals its processes of fusion way too willingly. Just when you’re starting to invest in the characters, they start dalliancing around the script itself, pulling down the fourth wall in a staged-as-sophisticated but increasingly disingenuous manner that left me dissatisfied and put off by film’s end. Still, it's a frothy experiment at storytelling, melding film with literature, even if breaking the fourth wall is hardly novel and has been explored more expertly elsewhere. For an informed analysis of this playful device, I recommend Catherine Grant’s essay “Breaking the Fourth Wall: Direct Address and Metalepsis in the Cinema and other Media” at Film Studies For Free.

The performances in Dans La Maison are playful enough, even if the characterizations are implausible, with a particularly notable debut by newcomer Ernst Umhauer as 16-year-old Claude who exhibits both a put-upon vulnerability and a slightly amoral adolescent menace; in other words, a classic puer leaving emotional devastation among the gullible adults in his wake. Kristin Scott Thomas co-stars in a characteristic pinched performance that is nonetheless pleasantly humorous. She’s an art gallery owner desperate to find art she can actually sell. Her exhibition of sexual dictators was my favorite self-conscious flourish in the film. The lovely Emmanuelle Seigner does the honors as Claude’s object of desire.

At Fandor, David Hudson rakes in the reviews from the film’s theatrical release, whereas Steven Erickson interviews Ozon. Earlier, Hudson reported on the film’s double-win at the San Sebastián Film Festival—the Golden Shell for Best Film and the Jury Prize for Best Screenplay—and its earlier win of the FIPRESCI prize for Special Presentations at last fall’s Toronto International.

Adapted from Juan Mayorga’s play The Boy in the Last Row, Dans La Maison (In the House, 2012) reunites Ozon and Luchini (who worked together on the clever Potiche), but to less winning effect, partly because it attempts to fuse too much together and reveals its processes of fusion way too willingly. Just when you’re starting to invest in the characters, they start dalliancing around the script itself, pulling down the fourth wall in a staged-as-sophisticated but increasingly disingenuous manner that left me dissatisfied and put off by film’s end. Still, it's a frothy experiment at storytelling, melding film with literature, even if breaking the fourth wall is hardly novel and has been explored more expertly elsewhere. For an informed analysis of this playful device, I recommend Catherine Grant’s essay “Breaking the Fourth Wall: Direct Address and Metalepsis in the Cinema and other Media” at Film Studies For Free.

The performances in Dans La Maison are playful enough, even if the characterizations are implausible, with a particularly notable debut by newcomer Ernst Umhauer as 16-year-old Claude who exhibits both a put-upon vulnerability and a slightly amoral adolescent menace; in other words, a classic puer leaving emotional devastation among the gullible adults in his wake. Kristin Scott Thomas co-stars in a characteristic pinched performance that is nonetheless pleasantly humorous. She’s an art gallery owner desperate to find art she can actually sell. Her exhibition of sexual dictators was my favorite self-conscious flourish in the film. The lovely Emmanuelle Seigner does the honors as Claude’s object of desire.

At Fandor, David Hudson rakes in the reviews from the film’s theatrical release, whereas Steven Erickson interviews Ozon. Earlier, Hudson reported on the film’s double-win at the San Sebastián Film Festival—the Golden Shell for Best Film and the Jury Prize for Best Screenplay—and its earlier win of the FIPRESCI prize for Special Presentations at last fall’s Toronto International.

Monday, April 08, 2013

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—UNA NOCHE / ONE NIGHT (2012)

Una Noche / One Night (Dir. Lucy Mulloy, Cuba, 2012, 90m)—As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "Briskly paced and brimming with atmosphere, Lucy Mulloy's electrifying debut chronicles an attempt made by two teenaged Cubans to set sail for Miami on a makeshift raft. Una noche is a fascinating portrait of Havana and its restless youth, caught in a cycle of perpetual desperate hustle." Una Noche arrives at IFF Panamá in their First Time Directors sidebar. Official site. IMDb. Wikipedia. Facebook.

Una Noche premiered at the 2012 Berlin International Film Festival and 2012 Tribeca Film Festival to international critical acclaim. The film shot to international media attention, ahead of its U.S. premiere, when two of the film's lead actors, Javier Nuñez Florian and Anailin de la Rua de la Torre, disappeared on their way to present the film at its Tribeca premiere, reportedly defecting to the U.S. In a highly publicized twist Javier Nuñez Florian and his co-star Dariel Arrechada went on to win the Best Actor Award even as Florian remained in hiding during the ensuing media frenzy.

At Variety, Justin Chang writes: "Marked by a vibrant evocation of Havana street life and excellent performances from three non-pro naturals, Una noche throws off a restless energy well attuned to its tale of impetuous Cuban teens preparing to make the dangerous ocean journey to Florida. Writer-director Lucy Mulloy's sexy, pulsing debut feature has an undercurrent of ribald comedy that doesn't entirely prepare the viewer for the harrowing turn it eventually takes, but it nonetheless amounts to a bracing snapshot of desperate youths putting their immigrant dreams into action."

At Indiewire, Gabe Toro adds: "There's a youthful energy running through Una Noche… [It's] alive and vibrant … at times funny, heartfelt, naughty and nice, a tale of three youngsters who deserve better than the forces that limit them, the corruption that eats away at their powerfully-beating hearts."

At Slant, Ed Gonzalez notes: "Lucy Mulloy is a tourist, but she understands Havana's complex sociopolitical situation better than most. Granted unprecedented and unbelievable access to shoot in the city ... the film realistically reveals the largest city in the Caribbean as a maze of history and discontent, it conveys the struggle of its characters to facilitate their escape from their island prison as a ramshackle puzzle desperately pieced together from a hodgepodge of ill-fitting pieces, some stolen, others acquired through bartering. ...Una Noche shines a light on the balseros phenomenon without miring itself in politics, such as discussions of the 'Wet Foot, Dry Foot' policy."

Una Noche premiered at the 2012 Berlin International Film Festival and 2012 Tribeca Film Festival to international critical acclaim. The film shot to international media attention, ahead of its U.S. premiere, when two of the film's lead actors, Javier Nuñez Florian and Anailin de la Rua de la Torre, disappeared on their way to present the film at its Tribeca premiere, reportedly defecting to the U.S. In a highly publicized twist Javier Nuñez Florian and his co-star Dariel Arrechada went on to win the Best Actor Award even as Florian remained in hiding during the ensuing media frenzy.

At Variety, Justin Chang writes: "Marked by a vibrant evocation of Havana street life and excellent performances from three non-pro naturals, Una noche throws off a restless energy well attuned to its tale of impetuous Cuban teens preparing to make the dangerous ocean journey to Florida. Writer-director Lucy Mulloy's sexy, pulsing debut feature has an undercurrent of ribald comedy that doesn't entirely prepare the viewer for the harrowing turn it eventually takes, but it nonetheless amounts to a bracing snapshot of desperate youths putting their immigrant dreams into action."

At Indiewire, Gabe Toro adds: "There's a youthful energy running through Una Noche… [It's] alive and vibrant … at times funny, heartfelt, naughty and nice, a tale of three youngsters who deserve better than the forces that limit them, the corruption that eats away at their powerfully-beating hearts."

At Slant, Ed Gonzalez notes: "Lucy Mulloy is a tourist, but she understands Havana's complex sociopolitical situation better than most. Granted unprecedented and unbelievable access to shoot in the city ... the film realistically reveals the largest city in the Caribbean as a maze of history and discontent, it conveys the struggle of its characters to facilitate their escape from their island prison as a ramshackle puzzle desperately pieced together from a hodgepodge of ill-fitting pieces, some stolen, others acquired through bartering. ...Una Noche shines a light on the balseros phenomenon without miring itself in politics, such as discussions of the 'Wet Foot, Dry Foot' policy."

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—7 CAJAS / 7 BOXES (2012)

7 Cajas / 7 Boxes (Dirs. Juan Carlos Maneglia & Tana Schémbori, Paraguay, 2012, 105m)—As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "A teenage delivery boy working in a popular Paraguayan market must dodge thieves, rival gangs and the omnipresent police when he undertakes a dangerous contract to transport a load of mysterious—and highly sought-after—crates to the edge of town in this frenetic, inventive thriller."

Winner of the Youth Jury Award at the San Sebastián Film Festival and positioned in IFF Panamá's First Time Directors sidebar, as well as one of the Teatro Nacional gala screenings, 7 Cajas might be low-budget but it's a "breakneck joyride that rivals Hollywood action movies for inventiveness and thrills-per-minute, but also conveys a rich and gritty sense of place, with a range of vivid characters. Meneglia and Schémbori make impressive use of their location, choreographing exciting and elaborate chase scenes using little more than people pushing long, wooden wheelbarrows." (PSIFF 2013) Official site. IMDb. Wikipedia. Facebook [Spanish].

At Variety, Robert Koehler assesses: "Turning the Paraguayan capital's biggest public market into an arena for a wild and cunningly plotted chase movie, filmmaking partners Juan Carlos Maneglia and Tana Schémbori build a rollicking entertainment with 7 Boxes. Certain to be one of the first titles from Paraguay to make a serious dent in the international marketplace, the pic makes a pleasurable surplus from minimal resources and plenty of ironic-comic-violent storytelling energy."

At Indiewire, Boyd van Hoeij describes 7 Boxes as "The Fast and the Furious with wheelbarrows" and adds: "Maneglia, who wrote the intricately structured screenplay, excels in keeping the twists and turns coming while keeping all his narrative balls in the air. And the final payoff is a doozy. City of God-like, agile camerawork by commercials cinematographer Richard Careaga is smudgy yet breathtaking, and combined with a pumping score that mixes electronic music and local, traditional instruments it delivers, well, the goods."

At Twitch, Kurt Halfyard deems 7 Boxes "genre-film bliss" and claims there are as many surprises in this film "as there are retail opportunities in the market." He concludes, "The storytelling confidence, the unaffectated acting, and, above all, a heightened grasp of plotting and logistics on display in 7 Boxes is astonishing."

Winner of the Youth Jury Award at the San Sebastián Film Festival and positioned in IFF Panamá's First Time Directors sidebar, as well as one of the Teatro Nacional gala screenings, 7 Cajas might be low-budget but it's a "breakneck joyride that rivals Hollywood action movies for inventiveness and thrills-per-minute, but also conveys a rich and gritty sense of place, with a range of vivid characters. Meneglia and Schémbori make impressive use of their location, choreographing exciting and elaborate chase scenes using little more than people pushing long, wooden wheelbarrows." (PSIFF 2013) Official site. IMDb. Wikipedia. Facebook [Spanish].

At Variety, Robert Koehler assesses: "Turning the Paraguayan capital's biggest public market into an arena for a wild and cunningly plotted chase movie, filmmaking partners Juan Carlos Maneglia and Tana Schémbori build a rollicking entertainment with 7 Boxes. Certain to be one of the first titles from Paraguay to make a serious dent in the international marketplace, the pic makes a pleasurable surplus from minimal resources and plenty of ironic-comic-violent storytelling energy."

At Indiewire, Boyd van Hoeij describes 7 Boxes as "The Fast and the Furious with wheelbarrows" and adds: "Maneglia, who wrote the intricately structured screenplay, excels in keeping the twists and turns coming while keeping all his narrative balls in the air. And the final payoff is a doozy. City of God-like, agile camerawork by commercials cinematographer Richard Careaga is smudgy yet breathtaking, and combined with a pumping score that mixes electronic music and local, traditional instruments it delivers, well, the goods."

At Twitch, Kurt Halfyard deems 7 Boxes "genre-film bliss" and claims there are as many surprises in this film "as there are retail opportunities in the market." He concludes, "The storytelling confidence, the unaffectated acting, and, above all, a heightened grasp of plotting and logistics on display in 7 Boxes is astonishing."

Thursday, April 04, 2013

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—CUATES DE AUSTRALIA / DROUGHT (2011)

Cuates de Australia / Drought (Dir. Everardo González, Mexico, 2011, 83m)—As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "A work of lyrical ethnography, Everardo González's Drought explores the isolated community of Northeastern Mexico's Cuates de Australia ranch. Cuates' inhabitants struggle with annual droughts, yet González emphasizes the richness of their way of life rather than their woes. The result is one of the most singular cinematic experiences on offer this year." As someone who grew up now and again working in the fields and on ranches, I had nothing but respect for the tenacious spirit depicted in Drought. Perseverance and humor furthers. González crafts a simple but effective alignment between the coming of the rain and the birth of new children. Winner: Best Documentary, Los Angeles Film Festival. IMDb. Facebook.

At Slant, Andrew Schenker writes: "Fixing its gaze on the parched landscapes of rural, northern Mexico and the people who survive the region's unforgiving climes, Drought is a portrait of a community under siege by forces beyond its control and its attempts to go about the daily stuff of life. Employing largely unobtrusive observational camerawork, spliced with a few interviews with the locals, Everado González's documentary brings to the screen both an eye for stark beauty in desolation and a sympathetic look at the citizens of the communal town of Cuates de Australia." At The Hollywood Reporter, Sheri Linden offers: "As he intended, González's feature transcends the genre of ethnography; he has shaped his eye-opening chronicle with a powerful aesthetic sensibility. Pablo Tamez and Matías Barberis' ambient sound is a fine complement to the visuals. Further heightening the material's impact, to haunting effect, are 1970s recordings of cantos cardenches—folk songs that are, fittingly, named after a type of cactus. With their aching melancholy, these a cappella numbers for three voices are the perfect accompaniment to the understated drama unfolding in this dusty terrain."

At Slant, Andrew Schenker writes: "Fixing its gaze on the parched landscapes of rural, northern Mexico and the people who survive the region's unforgiving climes, Drought is a portrait of a community under siege by forces beyond its control and its attempts to go about the daily stuff of life. Employing largely unobtrusive observational camerawork, spliced with a few interviews with the locals, Everado González's documentary brings to the screen both an eye for stark beauty in desolation and a sympathetic look at the citizens of the communal town of Cuates de Australia." At The Hollywood Reporter, Sheri Linden offers: "As he intended, González's feature transcends the genre of ethnography; he has shaped his eye-opening chronicle with a powerful aesthetic sensibility. Pablo Tamez and Matías Barberis' ambient sound is a fine complement to the visuals. Further heightening the material's impact, to haunting effect, are 1970s recordings of cantos cardenches—folk songs that are, fittingly, named after a type of cactus. With their aching melancholy, these a cappella numbers for three voices are the perfect accompaniment to the understated drama unfolding in this dusty terrain."

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—FIN / THE END (2012)

Fin / The End (Dir. Jorge Torregrossa, Spain, 2012, 90m)—As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "The first feature from Spanish director Jorge Torregrossa is a stunning apocalyptic thriller set against the awe-inspiring peaks of the Pyrenees, where a group of friends find themselves at the mercy of nature—and their own psychic demons—after a mysterious, all-encompassing blackout."

Elevated genre maintains its philosophical heights in Fin, which takes all the bite out of the ubiquitous zombie apocalypse to present a more chilling fade-out, as stars begin to blink out of the sky, and people disappear one by one from one second to the next off the face of the earth for no known cause or reason. By avoiding any evident external threat, nor offering any alternate explanation, the scenario achieves gravity and mysterious depth, becoming—as noted at the film's Palm Springs International screening—"a thoughtful meditation on human connectedness and individual identity." It's always lovely to watch Maribel Verdú, no less here than in Blancanieves—IFF Panamá's opening night gala—and the rest of Fin's good looking cast makes their disappearances one by one all the more poignant. Co-written with acclaimed screenwriters Jorge Guerricaechevarría (Live Flesh, Cell 211, The Oxford Murders) and Sergio G. Sánchez (The Orphanage, The Impossible), Torregrossa has created the rare genre film that's artful and thought-provoking as well as gripping entertainment. Official site [Spanish]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

For her program capsule for the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Diana Sanchez writes: "Brilliantly and relentlessly building the tension to a hair-raising pitch, Torregrossa's end-of-the-world allegory milks its sci-fi conceit for maximum suspense. Framing his protagonists against the majesty of a towering landscape that seems to dwarf the human drama played out beneath its indifferent gaze, Torregrossa transcends the boundaries of genre to offer a profound meditation on a fundamental philosophical question: what does it mean to exist, and to share that existence with others?" Of related interest, the Q&A for Fin's TIFF screening is available at YouTube. At Cineuropa, Alfonso Rivera states: "Beneath its appearance of a mainstream film, The End is, more than anything else, an existential film. It speaks of destiny, what we are, wounds from the past, and how we are conditioned by the gaze of those who surround us. ...A melancholy, psychological, and nihilist nightmare that Torregrossa has nourished with his obsessions: ambiguity, suppressed desire, and disenchantment. The result is a film that looks commercial—it is already being compared to the television series Lost—but that hides strong doses of depth." Cineuropa also hosts Rivera's interview with Torregrossa.

IFF PANAMÁ 2013—DESPUÉS DE LUCÍA / AFTER LUCIA (2012)

Después de Lucía / After Lucia / (Dir. Michel Franco, Mexico, 2012, 102m)—As synopsized by IFF Panamá: "The story of a teenage girl ruthlessly targeted by her classmates, Mexican writer-director Michel Franco's second feature is relentless, brilliant and timely: it is a convincing portrayal of modern bullying and a sober look at the excesses of Mexico's privileged classes. But also something timeless: a chillingly well-plotted study in entropy." Winner of numerous awards, including the prestigious Un Certain Regard prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the searing, intense Después de Lucía establishes Michel Franco as a major talent. Employing a rigorous and highly personal style that elevates subtext and visual clues over straightforward dialogue, Franco nails the emotionally devastating story, drawing restrained but utterly intense performances from leads Hernán Mendoza and Tessa Ia. Official site [Mexican]. IMDb. Wikipedia.

Shortly after its win at Cannes, David Hudson gathered initial reviews, namely National Post remarks by James Quandt; Charles Gant at Variety: "In no particular rush to articulate what exactly his characters are thinking and feeling, or to provide easy mood cues through music (there is none), Franco aims to engage through careful withholding"; and David Rooney at The Hollywood Reporter: "The film is of a piece stylistically with Franco's debut, Daniel & Ana, which premiered in the Directors Fortnight at Cannes in 2009. Austerity and rigorous control are his signature notes, with an unflinching realism marked by extended silences and a distinct preference for conveying information via oblique glimpses rather than in dialogue." He includes comments from Manohla Dargis's Cannes report for The New York Times. Meanwhile, at The Flickering Wall, Jorge Mourinha cautions: "If there is one film you should warn viewers beforehand about, that would be Mexican director Michel Franco's disturbing sophomore effort … a film at moments so unbearable you may well ask whether the director worships at the shrine of Michael Haneke's clinical entomology." Notwithstanding, Mourinha proclaims Después de Lucía "a work of staggering formal and narrative control."

As much as has been written about Después de Lucía with regard to its scathing indictment of peer bullying—and there's certainly enough of that on screen to make you furious—what remains most interesting to me was the very question asked by many of the audience members with whom I watched the film: "Why did Alejandra (Ia) allow herself to be bullied so severely by her classmates? Why didn't she tell her father or anyone in authority? Why didn't she fight back?"

The film's title implies the answer to those queries. Lucia, Alejandra's mother, has died in an automobile accident before the film has even started. Her absence is structural and within it smolders enough survivor's guilt to more than incapacitate any individual, let alone a young teenage girl. I appreciate that Franco has approached the self-inflicted damage of survivor's guilt with such a dry eye; but, even without manipulative music to cue emotion—and similar to his earlier film Daniel & Ana (which I didn't much care for)—Franco ruthlessly exploits the foibles of upper class Mexicans, almost to a fault.

Shortly after its win at Cannes, David Hudson gathered initial reviews, namely National Post remarks by James Quandt; Charles Gant at Variety: "In no particular rush to articulate what exactly his characters are thinking and feeling, or to provide easy mood cues through music (there is none), Franco aims to engage through careful withholding"; and David Rooney at The Hollywood Reporter: "The film is of a piece stylistically with Franco's debut, Daniel & Ana, which premiered in the Directors Fortnight at Cannes in 2009. Austerity and rigorous control are his signature notes, with an unflinching realism marked by extended silences and a distinct preference for conveying information via oblique glimpses rather than in dialogue." He includes comments from Manohla Dargis's Cannes report for The New York Times. Meanwhile, at The Flickering Wall, Jorge Mourinha cautions: "If there is one film you should warn viewers beforehand about, that would be Mexican director Michel Franco's disturbing sophomore effort … a film at moments so unbearable you may well ask whether the director worships at the shrine of Michael Haneke's clinical entomology." Notwithstanding, Mourinha proclaims Después de Lucía "a work of staggering formal and narrative control."

As much as has been written about Después de Lucía with regard to its scathing indictment of peer bullying—and there's certainly enough of that on screen to make you furious—what remains most interesting to me was the very question asked by many of the audience members with whom I watched the film: "Why did Alejandra (Ia) allow herself to be bullied so severely by her classmates? Why didn't she tell her father or anyone in authority? Why didn't she fight back?"

The film's title implies the answer to those queries. Lucia, Alejandra's mother, has died in an automobile accident before the film has even started. Her absence is structural and within it smolders enough survivor's guilt to more than incapacitate any individual, let alone a young teenage girl. I appreciate that Franco has approached the self-inflicted damage of survivor's guilt with such a dry eye; but, even without manipulative music to cue emotion—and similar to his earlier film Daniel & Ana (which I didn't much care for)—Franco ruthlessly exploits the foibles of upper class Mexicans, almost to a fault.