In their Fall 2011 issue, Moviemaker proclaimed the Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival (SDFF) as one of the "can't miss cool fests of 2011" and SDFF wears that laurel proudly, continuing to bring independent film to West Sonoma County for their fifth edition, which kicks off March 29 and continues through April 1, 2012. "Community is key at this doc fest," writes Moviemaker, "which serves as a catalyst for strengthening the local film community, developing an independent moviemaking program for nearby youth and eventually launching a year-round series of cinema screenings, salons and workshops."

In their Fall 2011 issue, Moviemaker proclaimed the Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival (SDFF) as one of the "can't miss cool fests of 2011" and SDFF wears that laurel proudly, continuing to bring independent film to West Sonoma County for their fifth edition, which kicks off March 29 and continues through April 1, 2012. "Community is key at this doc fest," writes Moviemaker, "which serves as a catalyst for strengthening the local film community, developing an independent moviemaking program for nearby youth and eventually launching a year-round series of cinema screenings, salons and workshops."My thanks to SDFF Program Director Jason Perdue for sitting down to discuss the festival's continuing growth, indicated this year by a multi-page program, an official opening night with reception, and new screening venues.

* * *

Michael Guillén: The proliferation of film festivals has been a subject of concern in recent years. What encouraged you to take on the challenge of creating a new film festival in an area inundated with film festivals?

Michael Guillén: The proliferation of film festivals has been a subject of concern in recent years. What encouraged you to take on the challenge of creating a new film festival in an area inundated with film festivals?Jason Perdue: That wasn't even part of the consideration, really. At the time that the festival's original founder Eliza Hemenway and the Sebastopol Center for the Arts decided to create SDFF, that concern wasn't necessarily the case. In Sonoma there was the Sonoma Valley Film Festival—which later became the Sonoma International Film Festival—and the nearby Mill Valley Film Festival. They were the two main festivals. Since then, several smaller niche festivals like our's have popped up; but, the key to our survival has been that—since the beginning—it was a documentary-only film festival. Documentaries are what inspired us and gave us passion and focus as programmers, and this has carried over to our audiences who have a love for documentaries.

Guillén: At what point did you take over from Eliza Hemenway?

Perdue: Eliza not only founded the festival but—in that first year—pretty much did everything. She set up the partnership with the Sebastopol Center for the Arts. By the time I got on board, she had been planning the festival with them for several months. She had just opened the call for entries and needed help taking a look at the first films.

Guillén: So you were on a screening committee?

Perdue: That's right. We helped her plan the event, but she already had it pretty much mapped out. She had secured the venue and had a shell of a website and four or five of us were brought in to help her screen the incoming entries.

Guillén: What was your background in film? How did you end up on that screening committee?

Perdue: I was really just a huge film festival fan. The first film festival I ever attended was the San Francisco International; a friend brought me to the closing night entry Crooklyn (1994) and Spike Lee was in the audience. I was instantly addicted. I was living in San Francisco at the time, working at the Stock Exchange, when I discovered many of the other community-based film festivals, as well as programming at the Roxie—IndieFest kicked into gear in the mid-'90s—but, I was just a consumer. I was just in the audience watching films and had my ideas of what did and did not work at these programs and always had in the back of my mind that programming a film festival would be a cool thing to do. But I didn't have any access and didn't know anything about putting on a film festival. Still, it became a passionate hobby. I would take weeks off to attend film festivals, became a benefactor of the San Francisco Film Society so I could take advantage of press screenings and one year saw more than a hundred movies; I was obsessed. So it was through that experience of attending film festivals that I developed my understanding of how festivals should work, at least from an audience standpoint. I didn't know anything about projection or filmmaking or even film criticism. I just knew what I liked or didn't like.

Guillén: So as a consummate cinephile, Eliza pulled you in to help her screen films and organize the festival. Then at one point you became the programming director yourself. It's perhaps obvious, but why did you decide to take on that role?

Perdue: I don't want to speak for Eliza, but after that first year of pretty much doing everything on her own, with some assistance from a core group of volunteers, she didn't want to go into a second year without divvying out duties. She wanted someone to at least take over as Program Director to organize the call for entries, to organize the screening committee and how films would be parceled out for consideration, to determine what the program was going to be and to make it happen. She wanted to be involved in other ways and having that piece of the festival off her plate would help her a lot. She put this out into the group and everyone didn't know what to do or say, but, after a couple of days I realized I wanted to try it. I volunteered and everyone said, "Great!"

Guillén: How fortuitous! I'm sure you recognize in retrospect that the opportunity to program a festival is a dream position for many people?

Perdue: Yeah, but here's the thing. We started from nothing and we had no contacts with other festivals so it wasn't like the word went out to the festival world. There were just four or five of us who knew that one of us was going to do what we considered to be basically a secretarial position. We didn't think of it as a coveted position. We had no plans of bringing in anyone from the outside. I will admit, however, that the moment I put the title "Program Director" under my name, my eyes opened to the opportunities for access.

Guillén: How important was the involvement of the Sebastopol Center for the Arts in helping you further this festival?

Perdue: The Sebastopol Center for the Arts is a 25+-year nonprofit institution in the town of Sebastopol that has tons of members, high visibility, and puts on events that a lot of people know about. Branding the festival back to the Sebastopol Center for the Arts was an ongoing challenge. A lot of people came to the festival in its first few years without any understanding that the festival was a program of the Center for the Arts; but, I'm confident the co-branding is now firm. Thus, the Executive Director of the SDFF is the Executive Director of the Sebastopol Center for the Arts (Linda Galletta). That relationship has allowed the festival to make it. The Center had a history of curating events; they had a built-in membership base interested in their events; and they had an established infrastructure of box office and volunteer coordination. Due to that, the SDFF didn't have to reinvent the wheel just to get started.

Further, as a fiscally-tight organization, the Sebastopol Center for the Arts has taught me a lot about how to run the festival in the sense that you don't spend a penny until you've brought it in. You don't make promises to organizations and individuals that you can't actually pay for.Guillén: I imagine working under the aegis of an established arts center has likewise helped in securing corporate sponsorship?

Perdue: Having a nonprofit status carries a certain cachet in corporate sponsorship and marketing spheres. They want to have their brand associated with an event in that nonprofit space, especially an event that's popular in the community.

Guillén: With the documentary genre as your niche focus, how did you strengthen that identity?

Perdue: Shortly after becoming the Program Director and sending out the call for entries, I got an email from a documentary filmmaker asking if I could waive the entry fee for his film? He described his film and I liked the sound of it so I agreed to waive the fee in exchange for his helping me to promote the festival in documentary circles. He promised to post information about SDFF to the D-Word, which is a website / bulletin board / social network—though it was created before that term came into existence—of documentary professionals that come together to support and help each other. When he told me about it, I joined up as a member and began promoting my event. Then filmmakers who screened at SDFF went back to this environment to report on the experience. They said, "Sebastopol is doing something special here." That was immensely meaningful for me and inspired me to continue.

Guillén: "Sebastopol is doing something special here." And then Moviemaker called you one of the coolest film festivals of 2011. Why? What had you done to distinguish yourselves? What makes SDFF "cool"?

Perdue: From the first year and every year since, it's always been about the programming; about finding the best films that we can and not pandering to the audience or worrying about premiere status or if the film has already shown in other festivals or if it's already available on Netflix. If we feel a film is a great film that has probably not been seen by most of our audience, we'll program it. When the filmmakers came to the festival and found the company they were in and began interacting with other filmmakers—many who had already won awards and done well with their films at other festivals—it proved an important experience to them. Our audience appreciated that they were being given a curated group of films, not a random group of films.

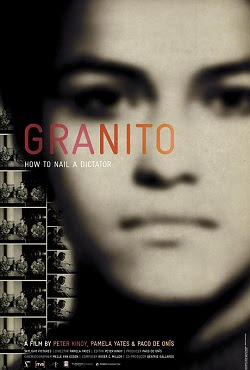

Guillén: I like that. A lot could be said about the distinction between programming films and curating films. When I first glanced through your glossy new program guide for your fifth edition of the festival, one of the first things that struck me was that the programming was a mix between new and tried-and-true films. Case in point: your Latino program spotlights the investigative work of Pamela Yates, which includes her invaluable 1983 entry When the Mountains Tremble coupled with her most recent film Granito: How To Nail A Dictator (2011). As value added, Yates will be in attendance at your festival to discuss both her films.

Guillén: I like that. A lot could be said about the distinction between programming films and curating films. When I first glanced through your glossy new program guide for your fifth edition of the festival, one of the first things that struck me was that the programming was a mix between new and tried-and-true films. Case in point: your Latino program spotlights the investigative work of Pamela Yates, which includes her invaluable 1983 entry When the Mountains Tremble coupled with her most recent film Granito: How To Nail A Dictator (2011). As value added, Yates will be in attendance at your festival to discuss both her films.Perdue: We've built a precedent for that kind of programming. In a previous edition we had the 25-year anniversary of Word Is Out (1977) with the entire directing crew present. My co-creative directors are both filmmakers who take the history of documentary film seriously—especially in the Bay Area where they're very much entrenched—and they don't want to lose touch with that. We have always managed to honor that history in some way.

Guillén: Let's talk about some of the other entries in this year's festival. Opening night is Mark Cousins' The First Movie (2009).

Guillén: Let's talk about some of the other entries in this year's festival. Opening night is Mark Cousins' The First Movie (2009).Perdue: It's a great film. I saw The First Movie at Silverdocs last year and immediately as soon as it was over said, "I've got to get that film." But let me be clear, all the members of the SDFF programming staff keep their eyes and ears open about what's coming up but we make no promises to anyone. If I see the greatest film I've ever seen at Silverdocs with my programming staff 3000 miles away, I will never tell a filmmaker, "We're going to show your film." Never. Because programming for SDFF is a collaborative effort.

Guillén: Did you know even then that it would be your opening night film?

Perdue: Not really. This is the first year that we're doing an opening night event with one film in a big venue where everybody's seeing the same film. We've never done that before. The first four years we showed four or five films in small venues all around town and then everybody came together for the opening night reception afterwards. So this is a little bit of an experiment for us.

Guillén: It's more a traditional structure to a film festival: opening night, centerpiece, closing night.

Perdue: I feel we've been bringing a film festival experience to Sebastopol in a lot of ways by bringing in filmmakers, bringing in films of various subjects, creating opportunities for conversation with the audience, creating the party environments, but the one thing we didn't have was the opening night experience. There's a difference between seeing a film with 100 people than seeing a film with 500 people and the opening night experience is something I wanted to bring to Sebastopol.

Guillén: Tell me about your special program "Peer Pitch".

Perdue: Peer Pitch comes from a Washington, D.C.-based organization called Docs in Progress, run for several years by Erica Ginsberg. As the title of the organization implies, they help documentaries that are in progress from the beginning stages of "I have an idea. I've sketched out this. I've shot this few minutes or hours and I'm not sure exactly what to do next" to "I'm almost done with this but I need some advice on how to either distribute or edit it or put the finishing touches on it." Docs in Progress works with filmmakers through classes. Every year Silverdocs schedules a Docs in Progress program called Peer Pitch, where they invite participants to do a no-pressure pitch of their work to a group of other filmmakers for feedback. I participated in Peer Pitch at Silverdocs this year and befriended Erica and—as I was preparing my festival—she said, "What do you think about bringing Peer Pitch to the West Coast?" I thought it was a great idea. I've opened up the space but she's pretty much organized the entire thing. She's rounded up the media and is running it as she runs it. People are signing up for it. It's definitely new for the North Bay.

Guillén: I firmly believe in the cross-pollination of ideas between film festivals to develop film culture, so I'm supportive of this collaboration between SDFF and Docs in Progress. Now, I don't intend to make you go film by film through this year's program, but what do you really want audiences to catch this year?

Perdue: I think our closing night film Everyday Sunshine: The Story of Fishbone (2010) is going to be huge. We're staging it at Hopmonk Tavern, which is the local venue where big bands come to play. We'll show the movie in the venue, then take down the screen, and then the band will perform in concert right afterwards. We're really excited about that. Fishbone was a band that was one of my favorites in the mid to late eighties. I went to several of their concerts in the Bay Area. We're partnering with Claypool Cellars, the winery owned by Les Claypool, who's the lead singer and bass player for the band Primus, and is featured in the film.

Perdue: I think our closing night film Everyday Sunshine: The Story of Fishbone (2010) is going to be huge. We're staging it at Hopmonk Tavern, which is the local venue where big bands come to play. We'll show the movie in the venue, then take down the screen, and then the band will perform in concert right afterwards. We're really excited about that. Fishbone was a band that was one of my favorites in the mid to late eighties. I went to several of their concerts in the Bay Area. We're partnering with Claypool Cellars, the winery owned by Les Claypool, who's the lead singer and bass player for the band Primus, and is featured in the film.Guillén: Sounds like a blast, Jason! Thanks for taking the time to talk with me today and I wish you the best with SDFF: 4 days with 53 films!