B. Ruby Rich has an endearing tendency of staring up into space when she's formulating ideas, as if they are flying around like elusive birds above her audience or—more accurately—projected larger-than-life on a big screen. She is a purveyor of visions and definitions. Five years ago she delivered the keynote address to Frameline's Persistent Vision Conference and returned to do the same this year at the Victoria Theatre. Conference Co-Coordinator Matthew Florence has provided an in-depth bio on Rich at the Persistent Vision website.

B. Ruby Rich entitled her keynote address "The Q-Word, the Post-Brokeback Landscape, Queer Normativity and the Genderation Gap"; a cluster of themes with which she has been preoccupied in the last year. "Where to start?" she asked her audience. "I have a heavy burden here. Do I want to claim New Queer Cinema yet again? Or dismantle it? Do I want to update it? Or trash it?"

Admitting she had come to praise New Queer Cinema, not to bury it, she quoted a comment made by Amy Villarejo in an essay written for GLQ (The Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies)—"The questions raised by queer studies, queer film studies, are still operative. It matters whether we choose to [embalm] them or resuscitate them, transformed for today." Qualifying that Villarejo was talking mostly about history, Rich nonetheless thought it could likewise apply to a reappraisal of queer cinema terms. "I suppose what I want to do here today is neither and both," she decided.

"What kind of landscape are we inhabiting now?" she asked. "Whether compared to five years ago when Persistent Vision was last held. Whether compared to 1992 when I first published my New Queer Cinema essay. Or whether compared to 30 years ago when a version of this festival first came into being."

She offered up a few examples. First, of course, the phenomenon of Brokeback Mountain. Secondly, a billboard that has sprung up all over New York City advertising Bravo's new show, Five Queens One Joker. "Guess which one is straight? It's a new kind of set up where the heterosexual's in the closet."

If Persistent Vision had been held last year, she would have talked about Queer Eye for the Straight Guy but, of course, that's old news by now and, after all, the show and its Fab Five have even become so mainstream that Thom Felicia went off last year to the World's Fair in Japan where he had been invited to design the U.S. pavilion. "I'm not even talking about The L-Word," Rich dismissed, "to which I of course pay slight homage in my title. But since it's happening this week, I think I'll just reference Rufus Wainwright performing Judy Garland. Was anybody there? No? We wish, huh?"

With queerness everpresent in cinema, television and popular culture, on the screens with Transamerica—"for better and worse"—and Brokeback Mountain, Rich noted that such emergences into the mainstream are read by some people as emergencies. One might call the situation "a push to queer normativity." But what has happened to the oppositional powers? The powers that the old original gay liberation movement was supposed to deliver? "Some of us," she recalled, "are old enough to remember the pledge to dismantle the nuclear family three decades before a new generation set about retrofitting it and rebuilding it instead." A weak smile came to my face remembering that distant, dusty pledge.

B. Ruby Rich has spent the last 10 months talking about Brokeback Mountain, much of which has gone into print; but, two of the best write-ups are the piece she wrote for the Guardian website and her interview with a young journalist named Cole Akers at the Orange County Weekly.

Notwithstanding, she wanted to point out a few things and provide a quick version. First, she disagrees with the mainstream critics who jumped on board to declare the western was always gay, providing an opportunity for all those guys—"Maybe you had some of them as film professors in college?"—who wanted to "suddenly declare they had seen Red River, they had seen this film or that film, and didn't they always know (wink wink) what was going on? I would argue that Brokeback Mountain does not belong in that setting. That, in fact, those westerns are about another kind of homosocial bonding and that it distorts the achievement of Brokeback Mountain as well as that of the genre to so glibly go into that comparison. Besides which, that should be our terrain to enjoy, not theirs."

But Rich also disagrees with so many of the queer critics who jumped on the bandwagon to attack Brokeback Mountain, to denounce it as "not even queer normativity, just mainstream normativity." Her favorite denunciation was Gary Indiana's in the Village Voice who complained that the film's credibility was stretched and completely unbelievable, reasoning that sexual attraction between Ennis and Jack couldn't have persisted for so long. Indiana pointed out—"and he didn't say 'In my experience', he simply declared it as fact"—that sexual attraction between men doesn't last past two or three years.

"I want to claim a proper lineage to the film," Rich explained. "Not the lineage that takes us back to—God help us!—John Ford, but, preferably the people who came after who did more interesting—to my mind—things with the genre." B. Ruby Rich has claimed Brokeback Mountain's "distinctly queer lineage", which is something of a "funny double-edged sword."

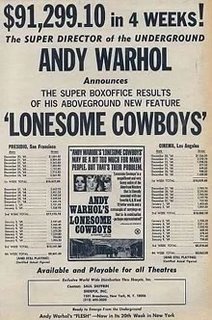

Andy Warhol's Lonesome Cowboys begins the list. Rich recalled that critics were dismissive of Brokeback Mountain saying, "This is nothing new. It's already been done. Look at Lonesome Cowboys." But, in fact, Lonesome Cowboys was interesting for another reason. "Lonesome Cowboys was shot in 1968 in Oracle, Arizona using a movie-ready main street that had actually been built originally for the early westerns. But while shooting there the Warhol superstars attracted the hostile attention of the locals who promptly reported them to the FBI and they became a target of an FBI investigation." If you explore some of the Warhol websites, you'll find references to the FBI dossier on Lonesome Cowboys.

Next, Rich would claim John Scheslinger's Midnight Cowboy, "the film that acknowledges the gay fascination with cowboys even if it doesn't quite create the cowboy fascination with being gay." Midnight Cowboy moved into the urban setting "where the New Queer Cinema of course would stay, where many of our great gay and lesbian films have stayed, but really it was a very groundbreaking film for its time and remains so in interesting ways."

Finally, her claim referenced Isaac Julien's "wonderful" video installation Long Road to Mazatlán shot in San Antonio, "deliberately referencing Warhol, deliberately referencing mainstream movies, as his central character repeatedly looks at himself in the mirror and does a strange update on Travis Bickel in the process, but there are cruising scenes—such as you might have expected to find in Brokeback Mountain—cowpokes cruising at the cattle auction. It's a wonderful imagining of a more contemporary queer sensibility relocated into a fantasy mythic western setting." These three films B. Ruby Rich claimed as the queer precedents for Brokeback Mountain.

Rich pointed out that aspects of the film that have been overlooked include "the class constraints of modern queer culture, the urban bias of the New Queer Cinema, all of which we see played out in this film that is indeed—as Marcus Hu and others have acknowledged—a working class love story. And finally the figure that etches indelibly into our retinas and our minds of the toxic patriarch. The family that smolders and strikes. The mother's powerlessness to save us from the father's wrath and disdain. And for lesbians of course in this eternally male-centric queer culture, the dad is who would save us from the moms who sometimes destroy us." But, of course, Rich mused, that film is one that no one has seen yet. She hoped we might get some hints as to why in one of the Persistent Vision panels aptly named "We Want Our Dykeback Mountain."

"Brokeback Mountain is most significant as a phenomenon," she continued, "More than a film, it's a phenomenon." Not just the Oscar parody. Not just The New Yorker cover. Not just the Boondocks cartoons. Not just all of the jokes and all of the quips and all of the articles—the countless articles!—but the breathless coverage that started when Brokeback Mountain won the award at Venice, which led to the Guardian giving her space to write about it, and then "ratcheted up" as the film was set to open. The incessant speculation on who would see this film, who would pay to see it, and how much money the film might make signaled to Rich "the arrival of a whole new sort of heterosexual hysteria. The box office litmus test. The homophobia of the cash register. How much you have to gross to be a player." In the old days when the New Queer Cinema was starting out in '91-'92, it was a million dollars. If you broke a million dollars, you were this wild runaway success that earned respect for queer representations. But in global ticket sales combined with something like $30 million already in dvd and video sales, Brokeback Mountain is now headed towards $200 million. "That's the new bar for respectability." But the most lasting contribution, Rich emphasized and she thanked Ang Lee for this, were the boundaries that no longer needed to be crossed, what she described as "the opening up of our terrain. The terrain to which we can lay claim. No longer just our town or our neighborhood, our friends, our social circle, our issues, our fights but a wide open world of movie genres and wild Western landscapes."

Already fascinated by Angela Robinson's D.E.B.S.—still a much beloved film for Rich and one which opened up the door to the world of popular mainstream genres—Ang Lee took it a step further and queered the most sacred of the genres—the western—and did it not just to these sacred characters of the cowboys and the ranchers—"Although sheep is still not cattle!"—but to the landscape; a queering of the Wyoming landscape that will never look the same again.

Further, Brokeback Mountain has also "annexed" history. Some critics have complained about that queer annexation. "But the very first impulse within queer cinema was toward history," Rich instructed. "It was Isaac Julien making Looking for Langston. It was Todd Haynes looking at the examples of Genet when he made Poison. It was Tom Kalin looking back at Leopold and Loeb when he made Swoon. It was a very strong historical impulse in that very very first encounter. Even some of the lesbian shorts like The Meeting of Two Queens [Dos Reinas] by Cecilia Barriga went back to Garbo and Dietrich. So there was in the very first instant a desire to annex history, to go back and look for precedents, and to assert our claim not just on today's stage but on that stage of the past that shaped us and that shaped our fantasies coming of age."

Rich raised the specter of Brokeback Mountain for another reason too. Since the film was released, she has been astonished at the re-emergence of a question that never seems to quite go away entirely: Why are these queer festivals still necessary? Why have a LBGTQQI festival when the marketplace has now taken over? Isn't it wonderful enough that queers are now in the mainstream? Why would we need these festivals now? On this theme she recommended Johnny Ray Huston's article in the current San Francisco Bay Guardian inspired by Mary Jordan's Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis talking about the kind of initial queer avant-garde impulse that Huston wants to see at Frameline, for which he values the festival. She likewise recommended Dennis Harvey's SF360 Frameline overview. For those up to the task, she pointed to indieWIRE's forum on indie queer cinema that rounded up a number of people to debate the topic, and the Village Voice section in 2002 on the 10th anniversary of her New Queer Cinema article which first appeared in the Voice. "Taking stock," she smiled wistfully. "It's odd this New Queer Cinema phenomenon, people constantly seem to have the need to take stock of it and I seem to keep going for the bait and rising to the occasion."

"So I've been trying to think through these issues myself and I want to run through a few parts of this article that I've done for GLQ," she said, "I've called this article 'The New Homosexual Film Festivals' in recognition of what my U.C. Santa Cruz students told me when I taught New Queer Cinema there last year. They said, 'Oh, queer is such an old word; we prefer homo.' " Her audience laughed with a groan. "I know," she responded, "I was surprised."

So what position do film festivals occupy exactly? This was a question Rich thought about five years ago at Persistent Vision. And now five years later the festivals that were then called Lesbian and Gay festivals are now called GLBT. "Festivals inhabit a really changed cultural and political landscape," Rich contextualized, "and not just in the ways I've just outlined. Not just in these fizzy ways. Transformed by predictable as well as unforeseen pressures…. Such pressures include the rise of homophobic and right wing Christian fundamentalist politics in the U.S., the tightening of all zones of tolerance under a national security state intent on not just the heterosexualization but the militarization of civilian life, increased homophobia masked as ignorance and indifference, generational differences within the queer community—what I choose to call 'genderational' differences—chronically underexamined class and race differences, the classically reappearing/disappearing lesbian question in all of this, the impact of the Internet and digital technologies … and the transformation of audiences by niche marketing, the increased seduction of queer viewers into willing consumers serviced by increasing commercial representational products and strategies. I think that investigations are more urgent than ever as a result as to what positions exactly the festival today inhabit, not only in the body politic but also in the political imaginary of their publics, those viewers who constitute themselves in hundreds of movie theaters and screening spaces around the globe into communities—however temporary, however ephemeral—of identity. …These audiences need to turn out constituting visible communities this time each year if only briefly and insuring the continual growth of the festivals themselves, in however conflicted and ambivalent a space."

Rich proposed it might be time for reception theory to get a workout again, that sociology students trained in statistics classes might point out the data on the lives, experiences, tastes and subjectivities of today's LGBT audiences. To be sure all is not well on the festival front. "It's not just this year after Brokeback," Rich qualified, "but virtually every year that the LGBT festivals are charged with outlasting their mandates and invited—if not ordered—to cease and desist. The frequency with which critics inside and outside of the queer community is issued this call to arms—or perhaps to disarm—is perplexing. The frequency is as constant as the message. Critics say that choices are available enough now in the mainstream to rule out the need for such specialization. Queer audiences are now a niche market, no longer viewed as ghettoized events. These [critiques] are a stale holdover from the pre-Stonewall era that survived like some sort of—I don't know—evolutional redundancy that by now we should succumb to the pull of Darwinism and surrender in some kind of Darwinian last gasp."

"What has been apparent instead," Rich elucidated "is the extent to which GLBT festivals may become repositories of that which the mainstream and popular culture, commercial culture, refuses to embrace. Not just in terms of style and aesthetic but in terms of issues and contents: which bodies are representable, which bodies are globally attractive, which themes are dignified?" She noted a similar pattern that has presented itself in other communities—the feminist film viewers of the '70s, the African-American festivals of the '80s—that entered the embrace of popular culture and, each time, the audience that was once so open to experimentation, so galvanized by witnessing its own representations, changed off to a commercial version once it became available. "It's not farfetched to see that pattern repeating itself."

On the other hand, Rich opined, such development forces the hand of the festivals "which will spin out into ever more courageous and experimental directions." In that regard she mentioned three trends. The first is the transgender revolution represented, not by the mainstream characters that have garnered Oscar nominations—thanks, Felicity!—"but by the increasingly accomplished works entirely framed and produced by trans-sensibilities and talents." Secondly, the rise of brilliant Third Queer Cinema outside the North American/Western European axis has brought increasingly challenging and fantastic films from Thailand, Mexico, Argentina, Hong Kong. Thirdly, "the fruition of digital storytelling, realized by low budget toolboxes," has brought work by younger and younger filmmakers and allowed "for the emergence of stories far from the urban centers and far from the film school training that has so long dominated the kinds of things we get to see."

Rich pointed out the MIX festivals in Mexico and Brazil as "powerful seedbeds to local production in this regard, a function of payoff with Julián Hernandez's first film A Thousand Clouds of Peace and this year with Broken Sky." Hernandez's "uncompromising and groundbreaking portraits of the young characters outside the mainstream" constitute for Rich the "reinvention of a true visceral erotic energy that just absolutely penetrates off the screen."

She profiled Mexican video artist Ximena Cuevas who has long been building a body of work back when digital was still called video. "Remember that?" Five years ago one of Rich's favorites of Cuevas's recent work—La Tambola [Raffle]—was "a wonderful demonstration of the discomfort that can still be inflicted on mainstream media. We don't enter into that space disguised but instead enter in as an undigestible other, as she does, the lesbian artist who refuses both submission and abjection on a wired, out of control t.v. talk show."

From Argentina, Rich highlighted the "queer empathic work" of straight filmmaker Diego Lerman whose film Suddenly (Tan de Repente) Rich described as a "lesbian romantic escapade." She amplified, "If you've never seen it or heard of it, you're missing your chance to see a young woman abducted at knifepoint by the lesbian street punks that desire her." Self-portrayals like Lucrecia Martel's The Holy Girl (La Niña Santa) and La Ciénega, both "subtly disrupt heteronormativity and make space for girls' homoeroticism."

Shifting focus to Brazil, Rich complimented such "wonderfully transgressive works" as Madame Sata, one of the films that she thinks has "created a new standard for transvestite—perhaps more than transgender—investigation."

Continuing her praise of Third Queer Cinema, Rich added, "Queer Asian filmmakers have been deploying really substantive bodies of work to challenge the West's definition of queer politics as well as aesthetics, and I think here of Stanley Kwan and his wonderful Tianneman Square tragedy Lan Yu; of Tsai Ming-Liang's evolving body of work, most astonishing, perhaps, with Goodbye, Dragon Inn and his queering of the movie theater and the supernatural cruising that goes on in the balconies of the abandoned theater. Or Apichatpong 'Joe' Weerasethakul [and] his melodramatic minimalism out of Thailand, such as Tropical Malady, where even the human is a container that must be breached for the welfare that eventually moves into the jungle and onto a tiger." With all three of these films hailed on the mainstream arthouse circuit, Rich conjectured that it would seem that LGBT festivals might again be considered redundant. But she cautioned that these films have been "imported for their aesthetics while their sexuality is left discretely at the door, unremarked upon by the mainstream cinephiles, even when the screen blazes with its evidence."

That point having been made, Rich then suggested that another function of LGBT film festivals that is worth protecting and honoring is the entire question of context. "It's only here in these theaters, in these audiences, that we can see these works for what they are," she proclaimed, "that we can hear audiences laugh and sigh, gasp and breathe in unison and realize the powers that can never be realized, never will be realized at home alone with the dvd player and the flat screen t.v. What these works mean and how they make that meaning, what they mean to us, still has to be fought for. LGBT festivals still have a lot of work to do in forging these connections between the international work from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the communities of color in San Francisco and the rest of the United States. Anyone attending the festivals can see always that audience development has a long way to go, though efforts in programming do sometimes pay off with diversified audiences."

Rich was particularly thrilled at last year's Frameline Festival with the audience of William E. Jones' documentary Is It Really So Strange?, his revelatory film about Morrissey's following amongst gay Latinos in the '80s who turn back to celebrate their own past and youthful folly. "Indeed," Rich theorized, "tracking the documentaries, both short form and in long form, offers an alternative perspective on festivals whereby political issues … enter into representation and dialogue. Last year was the year of gay marriage in San Francisco, but, of course this year is the year of gay marriage in Spain with Reinas having put into dramatic form what already got tested in documentary here. And other subjects continue to present themselves to demand attention. Every year it's something new. This seems to be the year of crystal meth from what I can tell. Crystal meth and gay men: 2006." Her audience chuckled sadly and knowingly. "It's one way of looking back at the Frameline sequence. And it's also one way that festivals offer an alternative to either the homo-ignored world of the mainstream journalism where only tabloid stories ever get play and the individualized world of Internet news where we must circulate and where no critical mass ever can get together for discussion or action. Our festivals are the place where we come together to constitute community. But what about the politics? When festivals begin to tie action campaigns into their screenings, perhaps something even more exciting than hook-ups might happen here."

Rich proposed that further diversification might well be aided and abetted by the strides and low cost of new production tools, even though this might blossom into a submission nightmare for programmers. But at the same time as these low budget tools are being introduced and made accessible to a more diversified filmmaking community, a parallel effort is required to create a low price ticketing structure for people who can't afford the tickets that others can. Rich reminded us that the poster child for a low budget production aesthetic is, of course, Jonathan Caouette and his infamous film Tarnation, which first attracted press attention at Sundance and then Cannes once Gus van Sant and John Cameron Mitchell signed on as executive producers. "But remember," Rich stressed, "it had its world premiere in the queer-specific space of New York's MIX festival whose director Stephen Jusick left to become its producer and—crucially—editing advisor, as it got cut down from—what? those of you who first saw it?—three hours? Three and a half hours? …Tarnation proved that a little money and a consumer I-Mac with the right life story and packrat habits could still break out of the pack, at least if you were an adorable white boy…."

Rich took this as another chance to start talking about the gender divide that has long stalked the New Queer Cinema and which is only getting wider. "Sadie Benning, where are you when we really need you?" she called out to her audience. "There's many many hundreds of Sadies now out there and you see them in the shorts programs and then we wonder what happens? What trips them up on the way to the feature? So I look forward to that [Dykeback] panel here to tell us why."

Then B. Ruby Rich proceeded to broach the topic that seemed to most agitate her audience. "Last year," she said, "Frameline dedicated its program theme to transgender work and here's the breaking news that I think is not really so new: that transgender is the new queer. It has the excitement, the uncompromising demands, the litany of oppression, the new representations, and yes, the youngsters. Stage center, a new generation experiences the LGBT universe as a cycling homonormative one. Just as much as my generation tarred our elders with a similar brush. What goes around comes around in identity politics. Now the transgender and genderqueer kids have their own digital productions, their own favorite productions, their own favorite films—I shout out to By Hook or By Crook, that genderqueer masterpiece. …At the moment, most of the heat is in short videos and dvds while the feature format belongs to the mainstream and the mainstream's more problematic use of such characters….

"The presentation of perspectives from within these emergent transgender or genderqueer communities are going to become increasingly urgent as the distorted images begin to circulate. But having been in the audience this year at The Believers and last year at The Aggressives, I can say something definitely is happening. The excitement that these films and videos is setting off is every bit as passionate and powerful as the original New Queer Cinema screenings of the early '90s and, truth be told, the late '80s as well. And that's why I dare make that assertion: that trans equals the new queer. But there's a difference. Queer was a word that was all about inclusion. Transgender, instead, is a very exclusive kind of club rather than an inclusive one. It's more like a new generation's version of the coming out story and that's why I call it the genderation gap, the transgender generation gap. In that sense—as a coming out story—it's already part of our lexicon, it already has a place set at the table, but in other ways it's ruffling feathers. There's lots of work still to be done. It has its own formulas that are just beginning to get articulated, its own narrative trajectories. Often the tragic ending in the mainstream versions is always about the discovery moment, the money shot as they say in porn, that requires in the mainstream versions the anatomical moment of truth and, of course, there's still a massive understanding and misunderstanding in equal parts, not just the characters in The L Word, the first time around, the second time around, but also—I don't know—let's see what this Lifetime show's going to be like. I think it's on tonight actually. A Girl Like Me: the Gwen Araujo Story, directed by of all people Agnieszka Holland, and starring Mercedes Ruehl as the sympathetic mom.

"And then the energy is still moving from documentary to fiction so I think we're still seeing a lot of the energy and a lot of the emergence of these stories in documentary and in shorts and they just gradually begin to move into longer formats.

"The festivals have served as launching pads for successive generations of communities and we can peep at the moments when queer first made its appearance. When gay and lesbians had to make room for bisexuals. Each of these moments were fraught with difficulty, fraught with excitement, moments that festivals had to engage with and transcend. But there's something I think important to point out about the genderation gap: queer was a word that was all about sexuality but it never was even remotely about gender. In fact, many argue that gender was unduly effaced under the sign of queer though, of course, that dilemma of lesbian erasure is hardly ameliorated by transitioning. The genderation gap forms the same violence to queer that queer did to gay and lesbian that gay and lesbian did to homosexual that homosexual did to homophile and so on. Who knows? We may get all the way back to the third sex if we keep going this way.

"…The international perspective of these festivals is even more urgent than ever as this country disappears more and more into an unknown xenophobia that closes its eyes to the rest of the world. The strengths as well as the weaknesses of the festivals can be found in their stalwart and solid march through the years. …I think there are also monuments erected on battlefields, a kind of movie image version of Gettysburg to which we all go on a pilgrimage. Like brick and mortar monuments, the festivals hold time capsules to years gone by surfacing in legacy shows, assembled by curators and scholars, always one of my favorite parts of the festival, the retrospectives and revivals staged by programmers and the historic excavations performed by filmmakers like last year's Dutch documentary Based On A True Story about tracking down John Wojtowicz, the "dog" of Dog Day Afternoon who was a real character whose gender crisis had provoked the famous bank robbery.

"The festivals are crucibles of identity for their attendees and like house of wax attractions that hold many such identities that viewers have outgrown, even if in some cases, we refuse to throw them out. …For the older generation shaped by civil rights struggles and equal protection under the law, as well as the middling generation shaped by AIDS and Act UP and the politics of confrontation, and the younger generation shaped by queer families and matter-of-fact sexualities, the newest kids on the block are always going to form a new round of shock and surprise. That's their role." The crucial role of the LGBT festivals, Rich defined, "is to provide a focus and a locus," a place where the ephemeral communities brought into being by this or that film or video program are coaxed out of their private worlds of flat screen wonders, Ipods, the cell phones "into community, into communion, into an encounter with one another."

"Gathering together in this age of privatization and surveillance and commodification, not to mention economic stress, is already a victory," Rich confirmed. "We have to find better ways to make use of the occasions, to extend the reach beyond this moment in June to create staging platforms for politics, discussion forums for issues, network platforms and year-round awareness that there are options beyond queer normativity, beyond following what the marketplace offers us, between toeing the line of a new status quo and succumbing to despair, to depression, to surrender. If we criticize our festivals it's because we need and love them so. We're here, after all, every year once again, aren't we?"

* * *

For those aroused by B. Ruby Rich's provocative voice, I further recommend Jennie Rose's 2004 Greencine interview, her 2004 State of Cinema address for the San Francisco Film Society, and her 2001 interview with Isaac Julien.