Let's hear it for the creative side effects of Christian indignation! In 1853, Charles Kingsley authored Hypatia, whose deliberate anti-Catholic tone incensed English Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman to pen his own novel Fabiola or The Church of the Catacombs, published a mere year later (currently available for online reading). Only loosely inspired by St. Fabiola, a Roman matron who converted to Christianity in the 4th Century, Wiseman's Fabiola situates itself earlier in time than the historical saint during the years of martyrdom when Christians were being persecuted under the reign of Roman Emperor Diocletian, but tracks narratively with the tale of a young Roman beauty spoiled by her father Fabius who—transformed through her witness of Christian charity and compassion—converts to Christianity.

Wiseman's novel was notable for weaving a number of martyrdom accounts and legends of real-life Christian saints into his fictitious story, and inspired three filmic adaptations. The first was an Italian silent version directed by Enrico Guazzoni in 1918 (available on YouTube). The second, the subject of this entry, was Alessandro Blasetti's lavish Franco-Italian film version Fabiola released in 1949. The third, a peplum film version called La rivolta degli schiavi (The Revolt of the Slaves) was directed by Nunzio Malasomma in 1960 (with Rhonda Fleming as the fabulous Fabiola!).

At his site Mercy and Mary, Catholic priest Fr. John Larson—an admitted admirer of Cardinal Wiseman's novel—has tracked the connective tissue from the book to its filmic adaptations, noting that the silent version "has many elements from the novel", including a strong focus on the characters of St. Agnes and St. Pancratius, with St. Sebastian playing less of a role, whereas in the 1949 version St. Agnes is missing altogether, with the characters of St. Sebastian and St. Tarcisius being more pronounced. St. Agnes returns for The Revolt of the Slaves, but Father Larson complains this version strays even further away from Cardinal Wiseman's book, "producing a rather forgettable result."

But, as with any true Roman Coliseum, for every thumbs down, there needs to be a thumbs up. At his site The Noel Network, Noel Thingvall offers a considered review that favors how "Blasetti and his squadron of writers, among whom were the top talents of the time, really made the material sing", in contrast to Cardinal Wiseman's "misinterpretation" of the historical material, whose book Fabiola Thingvall finds "naive, generalistic, and just plain stupid." Thingvall is on to something here. Where Fabiola may suffer from historical inaccuracy, it provides a strong cinematic story and—in its own way—a plea for tolerance. Having learned from Elaine Pagels that the Christian martyrdom of the 4th century has led to an almost entrenched if ideological sense of persecution intrinsic to that faith, it's with a wee bit of irony that one could replace the Christians for the Romans in this tale and a secularized American citizenry as the new face of martyrdom. But I digress.

My interest in watching Fabiola sprang from a cinephilic infatuation with French actor Henri Vidal, whose films Les Maudits (The Damned, 1947) and Une manche et la belle (A Kiss For A Killer, 1957) recently screened at the Roxie's French film noir series "The French Had A Name For It" programmed by Donald Malcolm and Elliot Lavine. In my interview with Malcolm, I admitted being smitten by Vidal, who responded: "I'm glad you appreciate Henri Vidal. I hope to show more of his work in future festivals. His is a sad story. He's a guy who got lost and died young. It's one of those 'might have been' stories. He could have been another Gabin in his own way. But Gabin persevered and was still there, whereas Vidal had a lot of troubles. He married Michèle Morgan and was in her shadow. I've not found a biography of Henri Vidal. I hope someone has written one and—if they haven't—I hope someone will because he's an interesting actor and a tragic figure. Well worth a book. Many of us would read it."

Naturally, that made me wonder if I shouldn't be the one to write such a book? Or at least an appreciative essay? And so I began researching and discovered that Michèle Morgan and Henri Vidal met on the set of Fabiola. At the time, Morgan's marriage to her first husband actor William Marshall was already falling apart and her affair with Vidal cost her dearly: Marshall divorced her and she lost custody of her son Michael. When Morgan eventually married Vidal, it seemed that her dream of love had finally come true, but within weeks of the wedding Morgan learned that Vidal had a serious, lifetime heroin-addiction and an issue with unbridled jealousy, such that her dream unraveled into an 11-year nightmare, ending with Vidal's death by heart attack on December 10, 1959 in Paris, France. He was only 40 years old. Susan French and Tony James chronicle Morgan and Vidal's ill-fated love story for their Times of Oman feature.

Yet, as Joni Mitchell's song attests: "It always seems so righteous at the start / when there's so much laughter / when there's so much spark / when there's so much sweetness in the dark." In their early love scenes for Fabiola, in the garden and at shore side, Morgan's beauty and Vidal's bracing good looks seem as destined for each other as it was prophesized for their characters in the film. Morgan plays Fabiola, the daughter of Roman senator Fabius Severus (Michel Simon) and Vidal is Rhual, a Roman soldier and secret emissary of Emperor Constantine, Rome's first Christian emperor. Meeting by chance, neither reveal their identities and share an evening of abandoned desire. Morgan's is the strongest performance in the film, exhibiting "just the right touch of icy sensuality" (Norton Herrick Center) and—more than a kneejerk conversion to Christianity—her transformation in the film has more to do with leaving behind youthful arrogance and privilege, and coming to the horrific insight that those who were allegedly her father's friends, were actually his murderers.

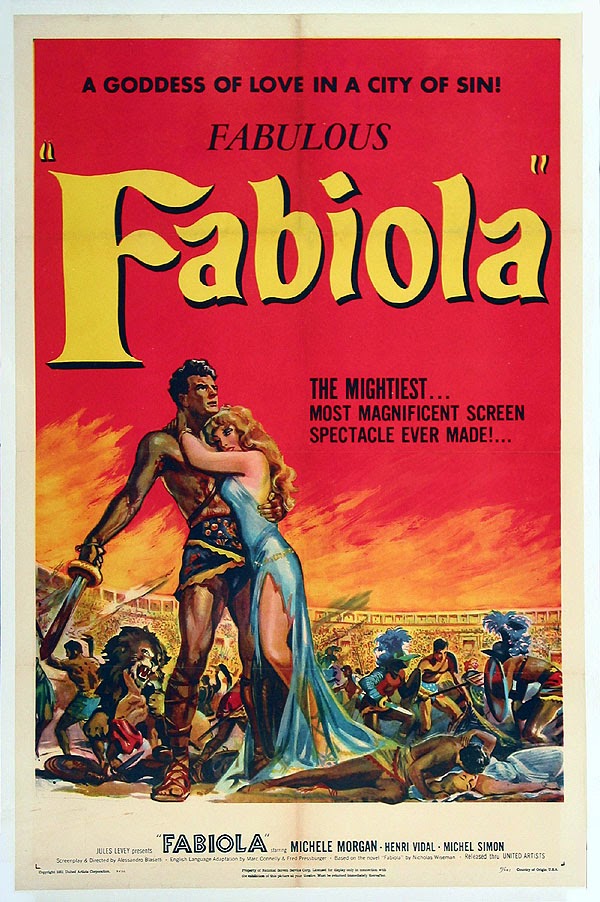

As detailed by Hal Erickson and Leonard Maltin, the Italian film industry's return to spectacle with the French / Italian co-production Fabiola came after several years of wartime austerity. Originally released in 1949 at a length of 183 minutes, Fabiola was distributed to the U.S. two years later in an English-dubbed 96-minute version, adapted by Marc Connelly and Fred Pressburger, retaining the action highlights but "cutting the plot footage to incomprehensible ribbons." It opened in the U.S. in 1951, becoming one of the year's box office successes despite its alleged incomprehensibility. The success of Fabiola paved the way for the onslaught of Italian costume epics in the 1950s and 1960s and, in that sense, is something of a "classic", if not merely "the granddaddy of all Italian spectacle films."

Although long out of circulation and—to my knowledge—unavailable on DVD, Fabiola can be seen on a 16mm transfer for a mere $3 on Amazon Instant Video; a bargain for beefcake! Although the dubbing makes Vidal sound like a frat boy, and he's alarmingly "frisky" at first (Thingvall, cited earlier, complains that Vidal "just won't stop moving ... constantly flexing and bounding his way through what should be thoughtful scenes, and even kisses with the rapid smack of a woodpecker"), there's enough on hand to make this sword-and-sandal spectacle an enjoyable diversion. For starters, Vidal looks fantastic! As does his co-star Massimo Girotti as the centurion Sebastiano of the Praetorian Guard; i.e., St. Sebastian. Rushing to avenge his friend Sebastiano at his scheduled execution, Rhual (Vidal) feeds into his Roman persecutor's hands by giving the impression that the Christian slaves are in revolt. As Sebastiano dies, Rhual swears a Christian oath never to kill another man, which sets the stage for his "turning the other cheek" at the gladiator games. He snaps a lance over his knee and throws away any weapons offered to him. This inspires the other gladiators so much that they follow his example and throw down their arms, just as Constantine's advance troops enter Rome bearing imperial banners displaying the sign of Christ. But don't fret! Before that happens there's a great sequence of Christians being tortured and fed to the lions. Nearly 50,000 extras were used for this sequence and—I don't care what anybody says—it has a visual human texture that CGI just can't touch.